Insight

June 16, 2022

PRIMER: The 340B Drug Pricing Program

Executive Summary

- The 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B) requires prescription drug manufacturers participating in Medicaid to provide outpatient drugs at a reduced cost to covered entities; these entities may then resell the drugs to patients and payers at higher rates, providing a revenue stream for charity care.

- The stated intent of 340B, implemented in 1992 as a part of the Public Health Service Act, is to “stretch scarce federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services”; the program originated after the Medicaid Best Price rule had the unintended effect of dramatically reducing charity prescription drug donations.

- The 340B Program involves numerous parts of the U.S. health care system both directly and indirectly—and at a value of over $38 billion a year, has become an integral part of the financial model for health systems across the country.

- This primer reviews the history of 340B and how the program functions.

Introduction

In order for a manufacturer’s drugs to be covered by Medicaid, the manufacturer must agree to participate in the 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B). Under 340B, manufacturers must provide discounts on outpatient drugs to eligible health care providers, who may then resell the drugs to patients or be reimbursed by payers at higher rates, providing a revenue stream for charity care. The program, implemented in 1992 as part of the Public Health Service Act, originated after the Medicaid Best Price rule had the unintended effect of dramatically reducing charity prescription drug donations. Its stated purpose is to “stretch scarce Federal resources as far as possible, reaching more eligible patients and providing more comprehensive services.”[1] In other words, the 340B discounts are intended to help hospitals provide more care to the indigent and uninsured.

The 340B Program is administered by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) and directly involves pharmaceutical manufacturers, pharmacies, and covered entities such as hospitals and health clinics, while indirectly involving a wide variety of health care system participants, including insurers, Medicare, Medicaid, group purchasing organizations, drug wholesalers, and pharmacy benefit managers, among others.

This primer reviews the history of 340B and how the program functions. An upcoming American Action Forum (AAF) will focus on how the 340B Program has fallen short of its goal, its most fundamental challenges, and potential reforms.

Background

In 1990, Congress created the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program (MDRP) to establish a ceiling price for drugs purchased through Medicaid. Under the statute, Medicaid became a “preferred provider,” requiring manufacturers to offer Medicaid the “best price” offered to any other health insurance provider.

Although the statute sought to lower the cost of Medicaid care, it contained no exception in the “best price” calculation for charitable giving. Before the statute was passed, many drug manufacturers regularly sold at a reduced cost or donated prescription drugs to health care facilities with high volumes of low-income patients in exchange for a tax deduction and the goodwill of the community. Under the 1990 statute, however, if a drug manufacturer donated drugs to any health care facilities it would be obligated to offer the drugs at the same price for all Medicaid patients. With this mandate in place, charitable giving fell significantly and facilities with high volumes of low-income patients had to absorb the added cost of providing drugs.

In 1992, Congress attempted to address the lack of voluntary pharmaceutical drug donations by amending the Public Health Service Act to create the 340B Program, overseen by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA). The stated purpose of the program was to “stretch scarce Federal resources.” The program functions by setting a “ceiling price” for what drug manufacturers can charge health care providers that qualify as CEs.

While these discounts were intended to target uninsured and low-income patients, the number of entities eligible for such discounts has increased dramatically over the years—particularly with the expanded definition of a CE provided in the Affordable Care Act (ACA), and separately, the broad definition of “qualified patient” for whom these discounts must be provided. Further, current law does not require these discounts be passed on to either the patient or the insurer—including the federal government—who pays for drugs obtained through the 340B Program. Insurers and the government pay the same standard rates for 340B drugs as for non-340B drugs, and uninsured patients pay varying amounts. A 2014 Office of the Inspector General (OIG) study of 30 CEs found that CEs do not consistently share 340B savings with patients and insurers.[2] Patients and taxpayers are therefore not necessarily benefiting from the mandated discounts.

How 340B Works

Covered Entities

There are several types of hospitals and clinics that qualify as CEs. For a hospital to be a CE, it must be: owned and operated by state or local government, a public or private non-profit delegated governmental powers by state or local government, or a private non-profit with a contract with state or local government to provide health care services to low-income individuals not eligible for Medicare or Medicaid.[3] With the exception of Critical Access Hospitals (CAHs), all other hospitals must meet a given Disproportionate Share Hospital (DSH) patient percentage (meaning the percentage of Medicaid and low-income Medicare patients seen by the hospital) in addition to other criteria.[4] DSHs, children’s hospitals, and freestanding cancer hospitals must have a DSH percentage higher than 11.75 percent, while sole community hospitals and rural referral centers must have a DSH percentage greater than or equal to 8.0 percent. Non-hospital CEs include Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) such as Title X family planning clinics, Ryan White HIV/AIDS clinics, and several other types of government-sponsored health clinics. As of 2015, nearly 90 percent of 340B CEs were either DSHs or CAHs.[5]

For hospitals, all sites of a single CE are considered a part of the CE as long as they are an integral part of the hospital, are registered with HRSA, and follow program rules.[6] This would include, for example, satellite clinics of an eligible hospital. If, however, multiple hospitals are owned by the same entity and each hospital files its own Medicare cost report, those hospitals must be individually approved by HRSA for 340B status.

CEs are prevented by statute from submitting a reimbursement claim to state Medicaid programs for drugs purchased through 340B and administered to a Medicaid patient. Given that drugs provided to the MDRP must be provided to 340B CEs, CEs must choose whether to “carve in” or “carve out” a Medicaid patient. Medicaid patients that are carved in may be provided 340B drugs and the state cannot claim the Medicaid rebate, while patients that are carved out receive non-340B drugs for which the state can claim the Medicaid rebate.[7] The goal of this division is to prevent a duplicate discount, wherein the hospital receives a discount for drugs through 340B and the state claims a rebate for the same drugs through the MDRP when it reimburses the hospital for the drugs’ costs.

CEs are also prohibited in statute from reselling a drug to a person who is not a patient of the CE. This is known as “diversion,” whereby an ineligible patient receives a 340B drug. The definition of an eligible patient, as noted below, is extremely broad.

All CEs are allowed to purchase drugs through the Primary Vendor Program (PVP) in which HRSA collectively negotiates for participants to gain additional savings on 340B drugs. CEs may also purchase directly from the manufacturer, through wholesalers, or group purchasing organizations (GPOs). Certain CEs, namely DSHs, children’s hospitals, and freestanding cancer hospitals are, however, prohibited from purchasing 340B drugs through a GPO.

Contract Pharmacies

A contract pharmacy is an external pharmacy that, as its name implies, a CE will contract with to dispense drugs to patients. A CE may use a contract pharmacy because the CE does not have its own pharmacy or to ensure broader reach to patients, among other reasons. Contract pharmacies agree to participate in exchange for a percentage of the 340B savings. In 1996, HRSA allowed CEs to contract only with a single contract pharmacy, but in 2010, the rules changed to allow for unlimited numbers of contract pharmacies per CE. In 2010, there were less than 1,300 contract pharmacies; in 2021, there were 29,971.[8]

Manufacturers

While there is no legal mandate that all pharmaceutical manufacturers must participate in the 340B Program, there is a heavy set of incentives for them to do so. For a pharmaceutical manufacturer’s drug to qualify for coverage under Medicare Part B, it is required to participate in the MDRP; to be eligible to participate in the MDRP, a manufacturer must provide discounts to the Veterans Administration and CEs in 340B.

Pharmaceutical manufacturers must report their average manufacturer price (AMP) and ceiling prices quarterly to HRSA and are prohibited from discriminating against CEs. This discrimination could include offenses such as requiring a minimum number of drugs to be purchased by 340B organizations or limiting drug sales to 340B providers in the event of a shortage. To ensure transparency, in 2019 HRSA established a website for CEs to check the ceiling prices of drugs to ensure they are paying manufacturers appropriate amounts.[9]

Eligible Patients

The statute does not define what constitutes a patient of a CE. HRSA regulations from 1996 state that a patient is considered eligible to receive 340B drugs from a CE if the following three criteria are met:

- The CE has an established relationship with the individual and maintains records of their health care;

- The individual receives services from a provider either employed by the CE or under contract with the CE such that the responsibility for care remains with the CE; and

- The individual receives services consistent with the services for which grant funding for FQHC look-alike status has been given to the CE (this specific criterion does not apply to hospitals).

This is an extremely broad definition of an eligible patient and has resulted in varying definitions of an eligible patient by different CEs.

Covered Drugs

340B prices apply to “covered outpatient drugs”—prescription drugs and biologics (excluding vaccines) used in an outpatient setting. Hospitals added to the program by the ACA cannot purchase orphan drugs—drugs for a rare disease or condition given a special Food and Drug Administration (FDA) designation—under 340B when those drugs are used for the condition for which they received their orphan designation.

Ceiling Price

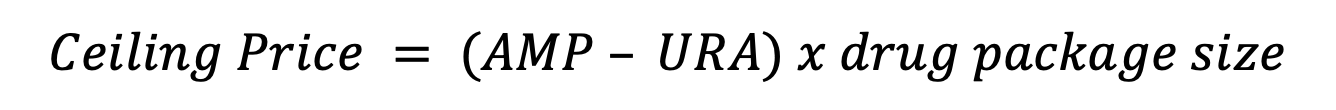

There is a statutorily set ceiling price for 340B drugs: the AMP minus the unit rebate amount (URA), multiplied by the size of the drug package, illustrated in Figure 1 below. The AMP is the average price paid to the manufacturer by wholesalers for community pharmacies and retail community pharmacies that purchase directly from the manufacturer. The URA is derived from the Medicaid rebate formula and varies depending on the type of drug.

- For single-source (brand name drugs with no generic version) and innovator multiple-source drugs (brand name drugs or their generic version marketed under an FDA-approved new drug application), URA is equal to the AMP minus the Medicaid best price or the AMP minus 23.1 percent, whichever is greater.

- Non-innovator multiple-source drugs (brands and their generics) have a URA equaling AMP times 13 percent.

- Clotting factors and exclusively pediatric drugs with a URA that is either the AMP minus 17.1 percent or AMP minus best price, whichever is greater.[10]

Figure 1

There is no cap to the ceiling price, and total discounts vary by drug, with MedPAC estimating a lower-bound average discount of 22.5 percent, though numerous drugs are discounted over 100 percent.[11] The ceiling price is not always what CEs pay, however. As mentioned above, CEs can participate in the PVP for additional savings. This has led over 80 percent of CEs to participate in the PVP, with average savings of around 10 percent below the ceiling price.[12]

Enforcement

Enforcement responsibilities are functionally split three ways among HRSA, manufacturers, and CEs. HRSA and manufacturers can conduct their own individual audits of CEs at the expense of the auditing party to ensure the absence of duplicate discounts and drug diversion. Manufacturers are required to submit quarterly price reports to HRSA to show the prices being charged CEs are within the statutory ceiling price. HRSA conducts audits of selected manufacturers and CEs to ensure compliance and requires manufacturers and CEs to recertify every year by updating their information in a 340B database and signing an attestation that they are in compliance. CEs and manufacturers are required to keep auditable records and report to HRSA when they are in violation of the rules of 340B or are no longer eligible for the program.[13]

Conclusion

The 340B Program, intended as a way to make up for the drop in charitable drug donations after the implementation of the Medicaid Best Price rule, has grown considerably since its enactment and now covers over 60 percent of U.S. hospitals, as well as countless FQHCs and other clinics. By allowing CEs to purchase drugs at steeply discounted prices from manufacturers and then re-sell to payers at higher rates, 340B aims to give CEs extra revenue to provide charity care. An upcoming AAF piece will discuss how the 340B Program has fallen short of this goal, the program’s inherent problems, and potential reforms.

[1] H.R. REP. NO. 102-384, pt. 2, at 12 (1992): https://protect340b.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/HRReport-102-384-II-p-12.pdf

[2] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-13-00431.pdf

[3] 42 U.S. Code § 256b

[4] MedPAC. Report to the Congress: Overview of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. 2015. https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program-pdf/

[5] Id.

[6] Id.

[7] Id.

[8] Fein, Adam J. 340B Continues its Unbridled Takeover of Pharmacies and PBMs. Drug Cost Institute. 2021. https://www.drugchannels.net/2021/06/exclusive-340b-continues-its-unbridled.html

[9] https://www.policymed.com/2019/05/hrsa-launches-new-website-to-identify-ceiling-prices-for-340b-covered-drugs.html

[10] Office of the Inspector General, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Part B Payments for 340B Purchased Drugs. 2015. https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-14-00030.asp

[11] MedPAC. Report to the Congress: Overview of the 340B Drug Pricing Program. 2015. https://www.medpac.gov/document/http-www-medpac-gov-docs-default-source-reports-may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program-pdf/

[12] Id.

[13] Id.