Insight

January 21, 2026

Private Credit: What’s the Fuss?

Executive Summary

- The U.S. private credit market – which refers to debt or debt securities that are not publicly issued or traded – has expanded rapidly in recent years with the asset class surpassing $1.7 trillion as of June 2023, a 10-fold increase since 2007.

- While private credit is a small fraction of the fixed-income market, its rapid growth, illiquidity, opacity, and interest rate structure have raised concerns about risks to broader financial stability.

- This insight provides an overview of the U.S. private credit market and discusses its benefits and risks.

Introduction

Private credit has become one of the fastest growing segments of the U.S. financial system, totaling more than $1.7 trillion in assets under management at the end of June 2023. Unlike publicly traded securities, private credit involves debt that is directly issued to borrowers by nonbank lenders and is not traded on open markets.

Private credit’s near exponential growth, illiquidity, opacity, and interest rate structure have raised concerns about broader risks to financial stability.

This insight provides an overview of the U.S. private credit market and discusses its benefits and risks.

The Rise of Private Credit

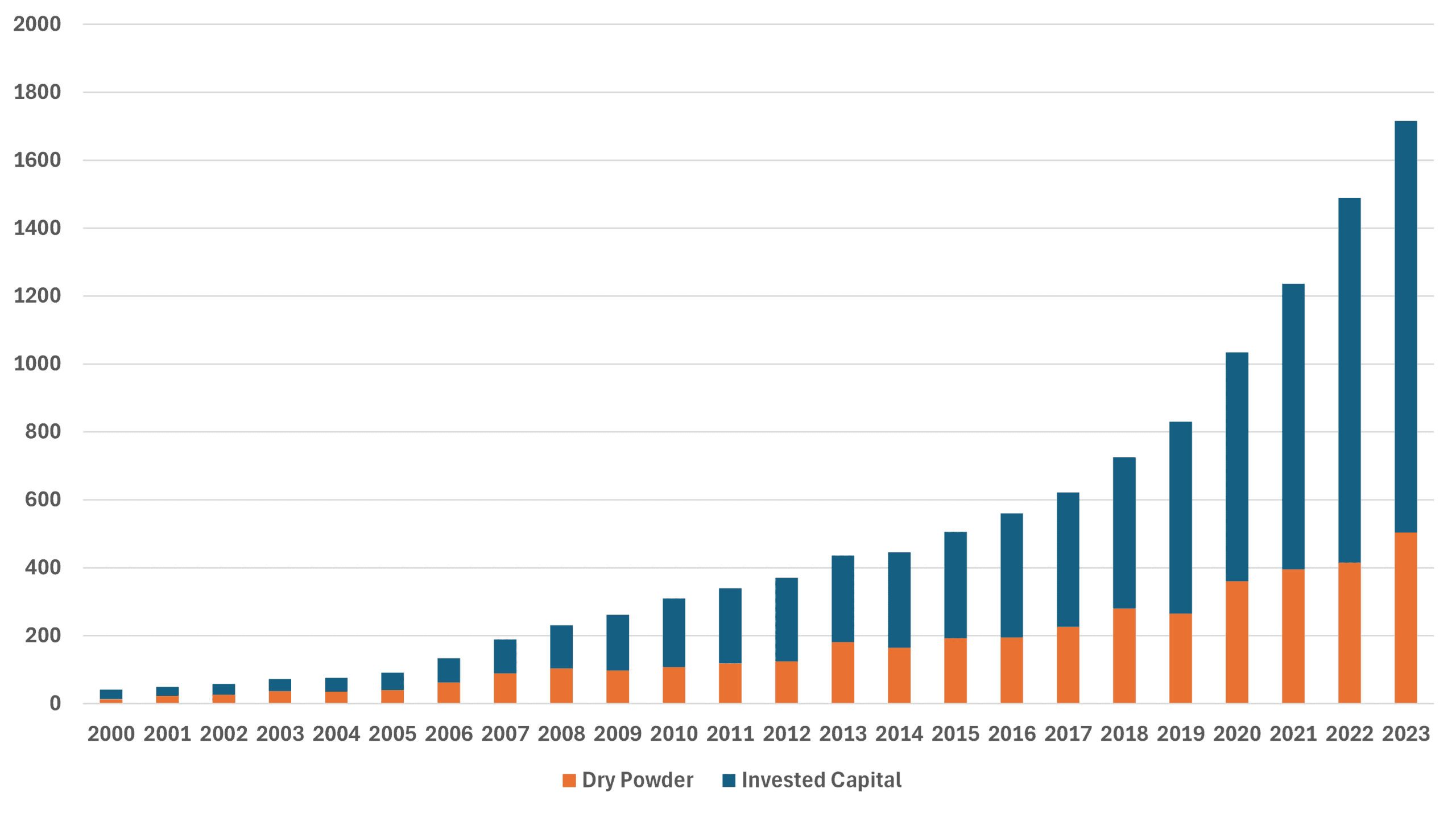

Private credit has grown exponentially in recent years, surpassing $1.7 trillion in assets under management (AUM) as of the end of June 2023, according to data from the Federal Reserve. AUM is the sum of invested capital – which is both committed and invested – and “dry powder” – which is committed, but uninvested capital. The size of this market has increased 10-fold since 2007 (Figure 1). McKinsey & Company estimated that the total addressable market for private credit in the United States could be more than $30 trillion, suggesting that the size of the market is likely to continue expanding.

Figure 1. Private Credit Assets Under Management, (Bil.US$)

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors; Data are as of December 31 except for 2023 which is as of June 29

Private credit’s meteoric growth underscores the industry’s increasingly important role in the broader financial system. Its popularity can be traced back to the 2008–2009 financial crisis and subsequent policy response. As interest rates cratered to near zero, yields on public corporate debt and U.S. government debt became less attractive. Investors seeking higher returns turned to alternative – and often riskier – assets including private credit.

At the same time, post-crisis banking regulations prompted large national and regional banks to curb lending to middle-market companies to meet more stringent capital requirements and improve their risk-based capital ratios. Private credit stepped in to fill the void.

Debt Markets Overview

Traditional Bank Lending/Public Credit

Banks engage in a process called maturity transformation: They take short-term customer deposits – a liability on the bank’s balance sheet – and convert them into an asset in the form of longer-term loans. This transformation inherently exposes the bank to liquidity risk as customer deposits funding these loans are redeemable at any time while loans are more illiquid. Banks earn a profit from the difference in the interest rate they pay on customer deposits and what they earn on the loan.

Federal Reserve regulations limit the share of deposits banks can convert into loans, requiring a portion to be held as reserves. An example of how this works can be seen below:

Customer A deposits $1,000 into Bank A → Bank A keeps a fraction (10 percent, for example) as reserves, leaving it with $900 in excess reserves → Bank A lends $900 to Borrower A → Borrower A spends $900, which becomes someone else’s deposit into Bank B → Bank B then lends $810 (90 percent of the $900) deposit → The process continues

Rather than hold these illiquid assets on their balance sheets, banks often pool multiple loans into a debt security, a process called securitization. Banks recapitalize by selling these securities to investors on public credit markets. Public credit markets are financial markets where debt instruments – including corporate bonds and U.S. government bonds – are openly traded.

A key feature of public debt markets is that securities trade on open exchanges, so their prices are visible in real time. Moreover, public credit instruments are highly standardized products, which “allows for efficient trading and widespread accessibility.” These products are also highly regulated. Issuers are “required to disclose financials, credit ratings, and material updates on a regular basis.” This provides transparency for primary buyers and secondary-market investors.

Private Credit

Private credit, meanwhile, refers to debt securities that are not publicly issued or traded, making them more illiquid compared to public debt. Nonbank lenders raise capital from investors to issue private loans directly to companies, typically small and middle-market firms, and regularly hold these loans to maturity.

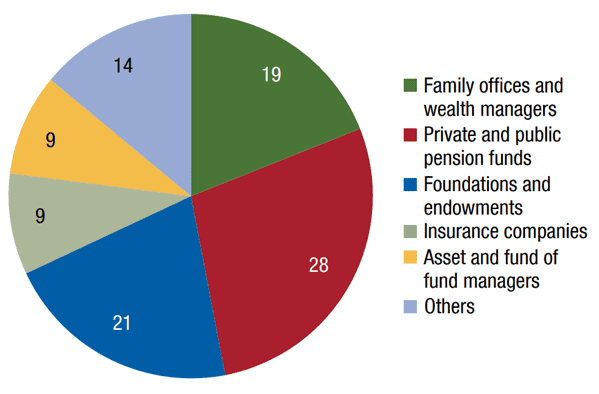

Data from the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) April 2023 Global Financial Stability Report showed that pension funds (28 percent), foundations and endowments (21 percent), and family offices and wealth managers (19 percent) were the largest groups of investors in private credit markets (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Investors in U.S. Private Credit Funds, 2022, %

Source: 2023 IMF Global Financial Stability Report

These groups of investors often have longer-term investment horizons, making the illiquidity premium of private credit an attractive investment compared to publicly traded debt. Moreover, private credit offers these investors diversification from public credit. Banks, by contrast, have more immediate liquidity requirements, making long-term investments in private credit less desirable.

The Details of Private Credit

Market Structure

Private credit funds raise capital from large institutional investors, pension funds, and insurance companies using different types of investment vehicles (Figure 3).

According to the IMF, closed-end funds are the most common private credit investment vehicle, accounting for 81 percent. Closed-end funds typically do not allow investor redemptions during the life of the loan.

A fast-growing segment of the private credit market is business development companies, or BDCs, which account for 14 percent of the market. BDCs raise capital from both retail and institutional investors and are also structured as closed-ended funds. Some BDCs allow redemption periods to appeal to retail investors, however.

The remaining 5 percent of the private credit market consists of collateralized loan obligations (CLOs). CLOs are structured into different tranches of private loans with different risk profiles.

Types of Private Credit

The Corporate Finance Institute (CFI) identified different categories of private debt, each with varying structures, repayment priority, and risk level. CFI explained that each type serves different borrower needs, from financing growth to managing financial leverage or restructuring debt. More details can be found in the Appendix section.

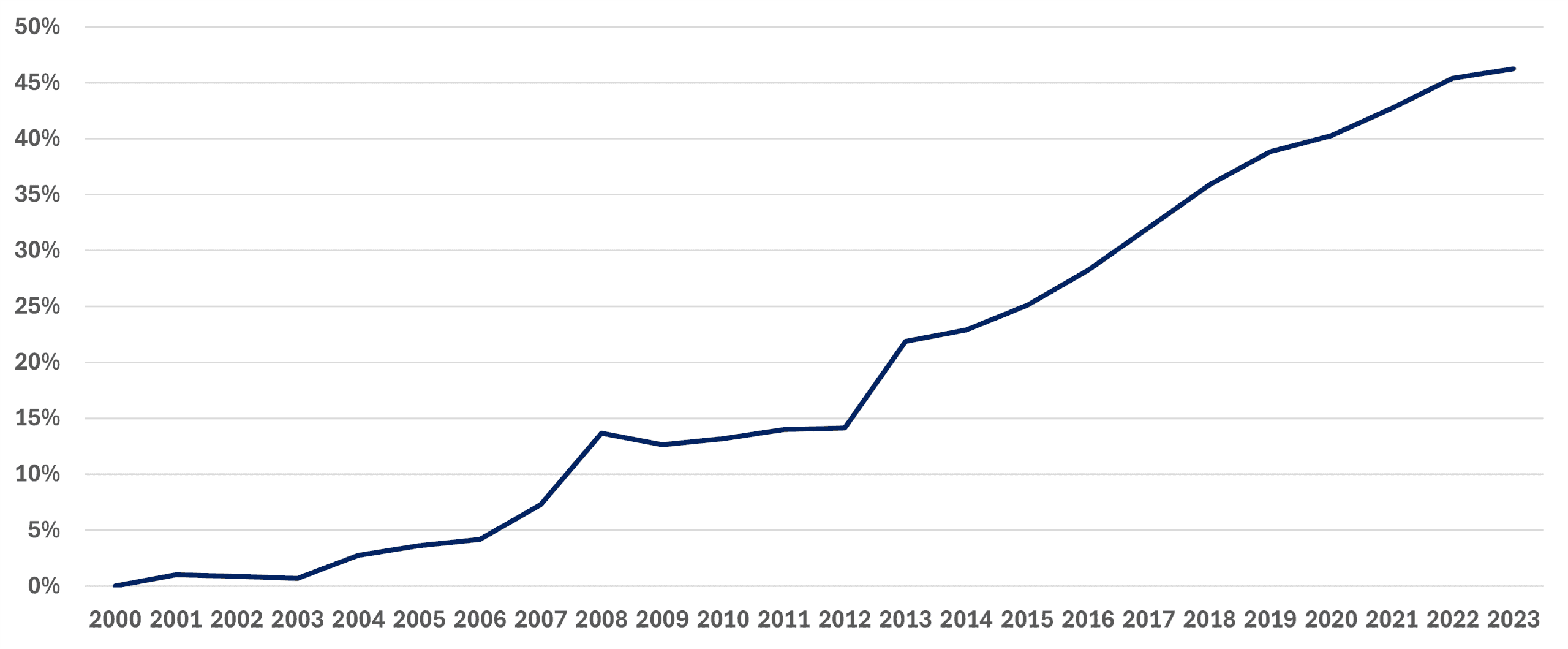

Data from the Federal Reserve showed that direct lending accounted for nearly half of all total private debt in 2023. Direct lending involves loans made directly to companies without an intermediary bank. These loans are privately negotiated with customized interest rates, debt covenants, and repayment schedules to match the borrower’s needs.

Figure 3. Direct Lending as a Share of Total Private Debt, %

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors; Data are as of December 31 except for 2023 which is as of June 29; calculated using Assets Under Management

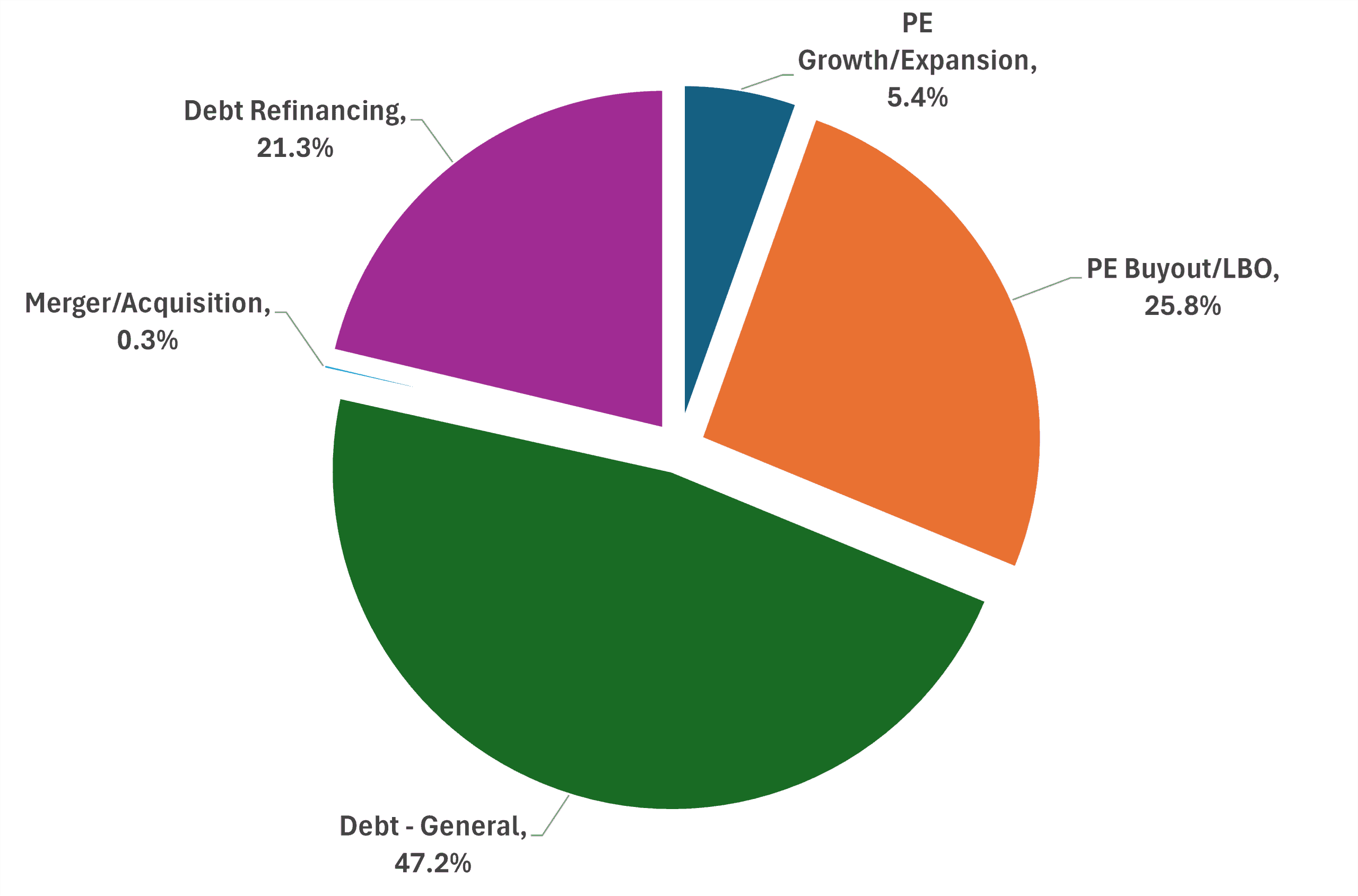

Private credit serves a variety of borrower needs. Federal Reserve data showed that almost half of private debt is used for general business purposes such as working capital (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Private Credit Deal Types (%)

Source: Federal Reserve Board of Governors

Who Uses Private Credit?

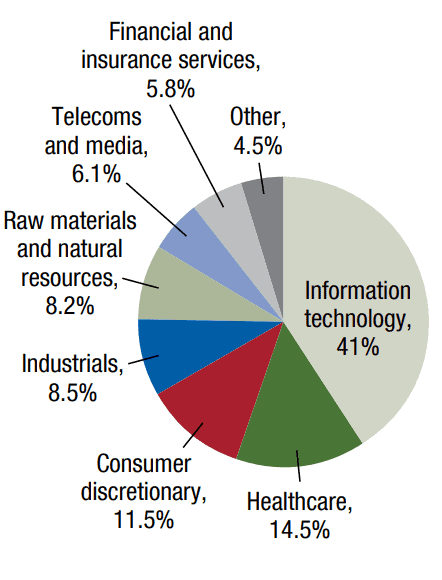

Private credit is most typically extended to middle-market firms that do not have access to public markets or for whom borrowing requirements are too burdensome for a single bank lender. Data from the IMF showed that information technology firms (41 percent) and health care (14.5 percent) are the two largest borrowers of private credit globally.

Figure 5. Private Credit Sector Allocation, by Last Three-year Deal Volume (Percent share by global deal volume)

Source: International Monetary Fund

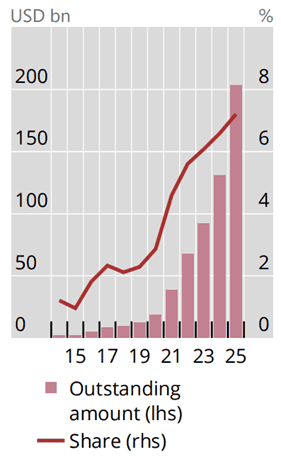

The artificial intelligence (AI) boom has spurred an even greater demand for private credit. Data from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS) showed that direct loans to AI firms have increased from nearly zero a decade ago to over $200 billion. The BIS estimated that “outstanding private credit to AI firms could reach around $300–$600 billion by 2030.”

Figure 6. Direct Loans to AI Firms

Source: Bank for International Settlements

Stakeholder Benefits and Risks of Private Credit

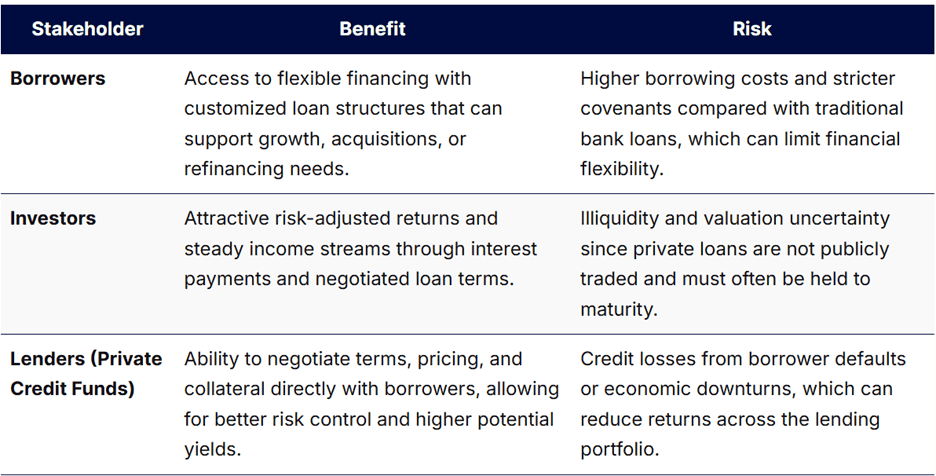

The CFI summarized the benefits and risks for each stakeholder in a private credit transaction (Figure 7):

Figure 7. Benefit and Risk by Stakeholder in a Private Credit Transaction

Source: Corporate Finance Institute

The IMF explained that “private credit offers borrowers a value proposition through strong relationships and customized lending terms designed to provide flexibility in times of stress.” Moreover, “private credit managers also claim to have much greater resources to deal with problem loans than either banks or public markets, thereby enabling fewer sudden defaults, smoother restructurings, and lower costs of financial distress.”

In other words, a proactive relationship between lender and borrower helps private creditors avoid the rigidity of public debt instruments in times of market stress.

Risks to Broader Financial Stability

The rapid rise in private credit has raised concerns about risks to the broader financial system.

Liquidity Risk

Private credit loans are illiquid, often with the investor holding the loan until maturity. Data from the Federal Reserve showed that the average maturity in private credit was 4.4 years. That is down from a peak of 5.6 years in 2021.

This lock-up period feature of private credit is likely a positive for system-wide stability. The most common private credit investment vehicle is closed-end funds, accounting for more than 80 percent of the market, according to the IMF. This, according to the American Investment Council, is the “antidote to the sudden, large withdrawals that are associated with ‘runs on the bank’ and forced ‘fire sales’ of assets, which was distinctive of the financial crisis.”

Floating Rates/Interest Premium

The Federal Reserve noted that almost all private credit loans are floating-rate – meaning they adjust as benchmark interest rates (e.g. Secured Overnight Financing Rate) adjust. These floating rates are adjusted every 30 to 90 days.

Private credit investors also demand a higher spread between the interest charged for the loan and the benchmark rate than other types of debt. This premium reflects compensation for increased credit risk and illiquidity.

Floating-rate structures can lead to increased borrowing costs on firms when rates rise. A prolonged period of high interest rates could threaten a borrower’s ability to repay.

Opacity

Much of the concern surrounding private credit is the lack of transparency. Private credit faces little price discovery in the underlying asset since the loan is typically held to maturity and not sold on open markets. The IMF warned that valuation uncertainty could incentivize fund managers to “delay the realization of losses.”

Moreover, the opaque nature of private credit makes it difficult for regulators to understand or quantify the connection the private credit industry has with the broader financial sector.

Systemic risk

Along with concerns about opacity and illiquidity, the Financial Stability Oversight Council (FSOC) identified financial stability concerns related to the interconnectedness among banks, insurers, and private credit in its 2024 annual report.

According to a Moody’s report, U.S. banks have lent $1.2 trillion to nondepository financial institutions, $300 billion of which has gone to private credit providers as of the end of June 2025. As previously discussed, short-term bank deposits are used to fund long-term loans that are then securitized and sold to investors on public markets. Concern arises when these short-term bank deposits are being locked up in long-term private credit, increasing liquidity risk. A private credit market event could spill over to the traditional banking system amid this increased exposure.

The FSOC warned that “a large and sustained increase in private credit default rates…could create financial instability through a number of channels,” including a “dash for liquidity.” Similarly, the FSOC warned that insurers’ “larger exposure to private credit may result in increased investment risk and liquidity risk…and uncertain valuations could reduce confidence in the adequacy of capital insurers hold.”

The opacity [or opaque nature] of the industry has made it difficult for regulators to assess the risk to the financial system. The FSOC “supports enhanced data collection on private credit to provide additional insights into the potential risks associated with the rise in private credit.”

The conclusions in the Office of Financial Research’s 2025 Annual Report to Congress, however, expressed less concern over systemic risk. The report stated that:

Leverage of BDCs and private credit funds is much lower than bank leverage. All but the most extraordinarily large credit losses on private lenders’ portfolios would be borne by their equity holders. The total amount of debt owed by private lenders is also modest relative to the aggregate size of the balance sheets of providers of such debt.

“Taken together,” according to the report, “these facts make it unlikely that distress at private lenders would transmit to the broader financial system.”

Conclusion

The growth in private credit has been exponential in recent years, providing capital to firms that are typically too small to access the public markets, or too risky to acquire financing from traditional banks.

Continuing to monitor the sector, specifically during periods of financial stress, can help regulators and market observers better understand the economic benefits to the economy as well as the systemic risks posed by private credit.

Appendix

Appendix I. Categories of Private Credit (State Street)

| Type of private credit | Description |

| Direct lending and corporate financing | Loans provided by non-bank lenders to individual companies, which can include a range of financing structures (e.g. ABF) |

| Mezzanine debt | Debt that sits between senior loans and equity, often including equity, such as warrants |

| Distressed debt | Buying debt of financially troubled companies, with the potential for restructuring or liquidation recoveries |

| ABF | Loans secured by physical assets such as residential/commercial real estate, aviation equipment, music royalties, machinery, and other assets |

| Real estate private debt | Financing for real estate projects, including bridge loans, construction loans, and mortgage-backed debt |

| Specialty finance | Lending in niche areas like litigation finance, royalties, aircraft leasing, or trade finance |

| Structured credit (CLOs, ABS, etc.) | Investments in securitized loans, such as collateralized loan obligations (CLOs) or asset-backed securities (ABS) |

| Infrastructure debt | Financing for infrastructure projects such as energy and utilities |

Source: State Street Investment Management

Appendix II. Categories of Private Credit (CFI)

Direct Lending

Direct lending involves loans made directly to private companies without an intermediary bank. These loans are typically used for business expansion, acquisitions, or refinancing. Because they are privately negotiated, lenders can customize interest rates, debt covenants, and repayment schedules to match the borrower’s financial situation.

Mezzanine Debt

Mezzanine debt blends characteristics of debt and equity. It ranks below senior secured loans but above common equity in repayment priority. Borrowers use mezzanine financing to fund growth or acquisitions when senior debt alone isn’t sufficient. Investors accept higher risk in exchange for higher returns, often through a combination of interest payments and equity warrants.

Distressed Debt

Distressed debt refers to loans or bonds from companies experiencing financial difficulties or facing bankruptcy. Private credit investors in this space seek to profit by purchasing the debt at a discount and working toward a turnaround or restructuring that increases its value. These investments require deep financial analysis and active management.

Asset-Based Lending

Asset-based lending (ABL) involves loans secured by collateral such as accounts receivable, inventory, or real estate. The loan amount depends on the value of the pledged assets, reducing credit risk for lenders. ABL is common among businesses with strong asset bases but limited cash flow or short-term financing needs.

Source: Corporate Finance Institute