Insight

November 10, 2016

Retrospective Review Case Study: Securities and Exchange Commission

The Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) recently released its annual notice, as required under Section 610 of the Regulatory Flexibility Act (RFA), to solicit comments on a set of rules from 2005 to determine whether they “should be amended or rescinded to minimize any significant economic impact of the rules upon a substantial number of such small entities.” These rules impose total costs in excess of $2 billion and a paperwork burden of nearly two million hours annually – a significant set of regulatory burdens. But can Americans expect to see significant consolidation, revision, or rescission of some of these requirements? Unlikely. In fact, recent history shows that the Section 610 review process and President Obama’s Executive Order (E.O.) 13579 (encouraging independent agencies to undergo regulatory review) have all failed to produce meaningful results in retrospective review of SEC rules.

Section 610 Review

Below are the rules in SEC’s notice that contained at least some sort of monetized regulatory cost or paperwork burden estimate.

|

Regulation |

Total Cost ($ Millions) |

Annual Costs ($ Millions) |

Paperwork Burden Hours |

|

XBRL Voluntary Financial Reporting Program on the EDGAR System |

|||

|

Mutual Fund Redemption Fees |

|||

|

First-Time Application of International Financial Reporting Standards |

|||

|

Regulation NMS |

|||

|

Use of Form S-8, Form 8-K, and Form 20-F by Shell Companies |

|||

|

Rulemaking for EDGAR System |

|||

|

Securities Offering Reform |

|||

|

TOTALS |

2,026.30 |

594.25 |

1,899,924 |

Interestingly, one of the highlighted rules, “Securities Offering Reform,” is already a deregulatory measure. Although, per the rule’s introduction, this rulemaking comes from an internal review process under the Securities Act instead of a Section 610 review. Its reductions of $59 million and 40,000 hours pale in comparison to the combined totals of the other rules in the notice.

However, the top-line cost figures are largely illustrative for the purposes of Section 610 review as that process focuses on finding ways to alleviate small entity burdens. One would presume that the agency would solicit comments under notices like this one and then undertake rulemakings to amend those past rules and eventually there would be a final rule that would revise or add to the Code of Federal Regulations.

For SEC though, this process does not appear to have yielded any real reforms. A search of the Federal Register for SEC final rules that contain the query of either “Section 610 of the Regulatory Flexibility Act” or, more simply, “Section 610” yielded zero results. This signifies that SEC has yet to finalize any potential reforms under this process into law. The SEC is actually an anomaly, as searching for final rules with “Section 610” across all agencies and years yields almost 200 final actions.

One potential reason for this may be the lack of input from stakeholders. Remember, these notices are merely soliciting comment from interested parties about how best to update potential RFA issues. As the below table shows, reviewing the dockets of these notices in recent years yields a meager level of input.

|

Year Examined |

Number of Comments |

*See “File No.: S7-02-14”. No comment docket link. Only a submission link.

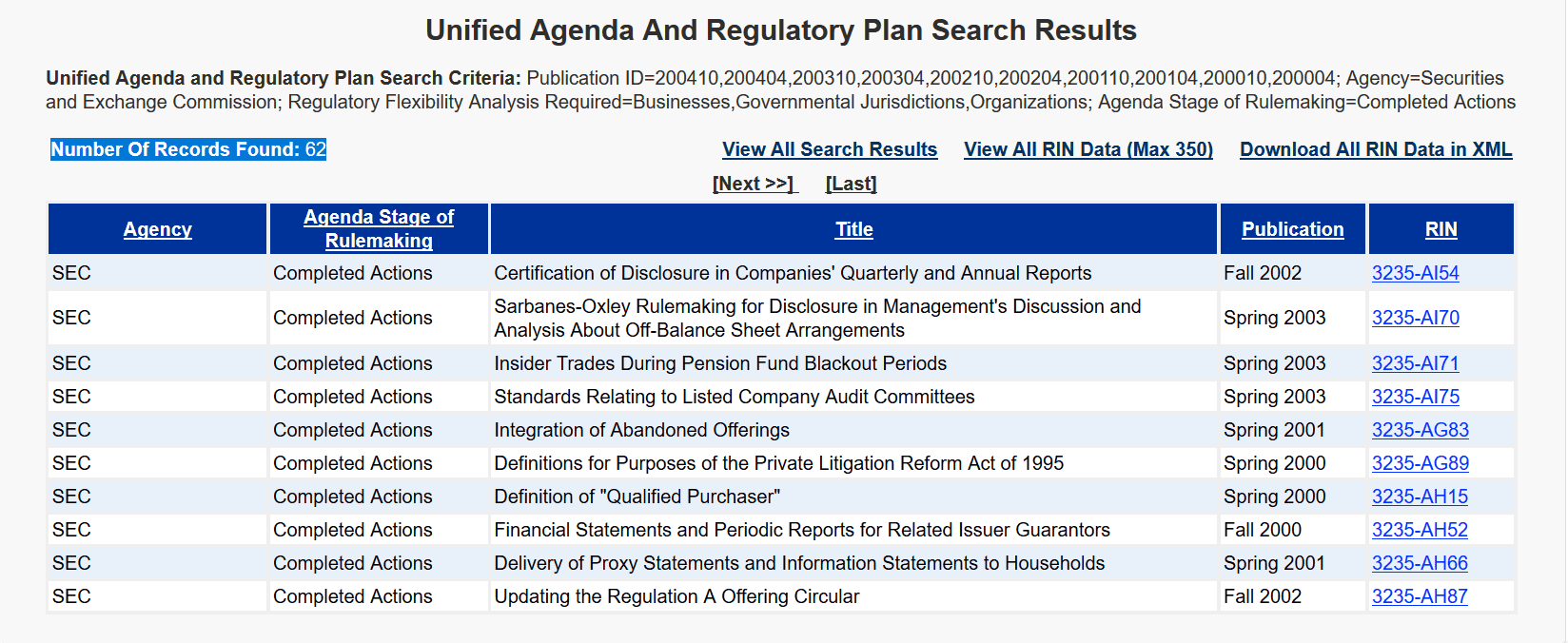

Across the past 5 years, a given SEC Section 610 notice would receive an average of one comment per year. Could it be that there weren’t enough SEC rulemakings over that period with an RFA designation worth reviewing? Considering there were 62 such rulemakings over that span (see below), that seems unlikely.

No input means that the agency likely has limited incentive to revisit these rules. And thus, the feedback loop established by Section 610 ends up failing. The most plausible explanation is perhaps that this is not a particularly well-known or publicized process. And while there may be more that stakeholders can do to contribute to the retrospective review process, agency-driven review over recent years has been deficient as well.

Executive Order 13579

In 2011, President Obama issued Executive Order 13579 asking independent agencies to follow a similar retrospective review process as the one laid out in Executive Order 13563 for Cabinet-level agencies. Since the president has limited-to-no direct power over most independent agencies (except for perhaps nominating authority), the “order” is largely a suggestion. Independent agencies – such as SEC – have made little headway examining and amending past rulemakings.

The lack of activity from SEC is particularly striking. A search query for “Executive Order 13579” yields only one rulemaking document: the notice soliciting comments for potential reform targets. A search of SEC’s Regulatory Actions section yields just two documents: another version of the comment notice and a comment petitioning for regulatory changes that cites the Executive Order once. As in its absence of results under Section 610 review, SEC is unable to join the ranks of the agencies that have produced at least 26 actionable items under the E.O. Unlike its Section 610 review history, it cannot blame the scarcity of input for its inaction; its docket for suggested reviews contains 77 comments.

Potential Reforms

Policymakers have recently proposed remedies to the deficient review histories of agencies like the SEC. In 2015, the House passed H.R. 527, the “Small Business Regulatory Flexibility Improvements Act.” Among various other changes to the RFA, H.R. 527 would address this problem by requiring greater transparency and notice of agency reviews and empowering stakeholders through a more active role for the Small Business Administration Office of Advocacy and judicial review.

While not directly addressing retrospective review, S. 1607, the “Independent Agency Regulatory Analysis Act,” would compel independent agencies to follow the same cost-benefit standards as those under Executive Order 12866. This would be an important stepping stone towards retrospective review in independent agencies, since many of them largely do not preform even an original cost-benefit analysis. However, following a similar track as executive agencies may not automatically work considering how executive agencies have somehow added $22 billion in regulatory costs under their “retrospective” review plans. Legislation that would codify E.O. 13579’s basic directives for independent agencies with oversight from Congress – which generally has oversight authority over their respective budgets – instead of the executive branch might improve results.

Conclusion

Retrospective review of old regulations ought to be among the best practices of any agency. The world of regulatory review is often tedious and mundane. It doesn’t usually get many headlines. As such, some independent agencies like SEC are able to escape scrutiny in their efforts. By making almost no progress under either RFA’s review progress or E.O. 13579, SEC stands as a major example of this. With more than $16 billion in regulatory costs imposed since 2006 and expanded powers and mission under Dodd-Frank, it’s time to start taking a harder look.