Insight

April 13, 2023

Reviewing the Biden Administration’s Latest Update to Regulatory Review

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Biden Administration recently unveiled a more detailed vision of its proposed changes to how agencies and the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs consider and support the rationales behind regulatory actions.

- The core changes involve adjusting the threshold at which rules face more rigorous reviews, refocusing agency rulemaking practices toward addressing concerns of “underserved communities,” and updates to how agencies calculate their cost-benefit analyses.

- While some of the changes are well-intentioned and likely overdue, it is important to consider their potential consequences – intended or otherwise – and monitor the administration’s implementation of these provisions.

INTRODUCTION

On the day of his inauguration, President Biden issued a government-wide memorandum entitled “Modernizing Regulatory Review,” a sparse document primarily outlining the core regulatory principles one could expect from the new administration. While the document did not provide clarity on the implementation details, some raised concerns that it sought to give greater license to agencies to use “non-quantifiable” benefits to further tip the scales in the favor of a given rulemaking’s cost-benefit analysis. Now, with a recently confirmed Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) administrator at the helm, those details are becoming clearer.

On April 6, President Biden issued an Executive Order (EO), also entitled “Modernizing Regulatory Review,” that includes a series of more tangible policy positions based on the inaugural memo. Following that EO, OIRA issued a series of memoranda and other documents that seek to fill in the details of how agencies conduct certain aspects of the rulemaking process and produce their regulatory analyses. While these proposed policies fall well short of some grand paradigmatic transformation in regulatory philosophy, they do, in ways both subtle and pronounced, represent a significant shift in when, why, and how agencies engage in regulatory analysis to justify their rulemakings. In terms of practical effects, these updates – intentionally or otherwise – will likely result in a somewhat less rigorous review process. The changes may also allow agencies to justify more costly actions under the pretext of more expansive benefits.

RUNDOWN OF NOTABLE CHANGES

New Threshold for “Economically Significant” Rules

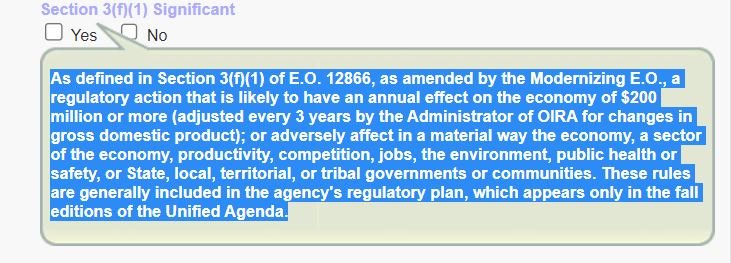

The memo’s guidance to agencies for implementing the EO in the development of their regulations notes that the EO “reaffirms the principles governing regulatory review as set forth in [EO] 12866 (Regulatory Planning and Review) and [EO] 13563 (Improving Regulation and Regulatory Review).” Despite that broad reaffirmation, there is one particularly significant change to the framework established under EO 12866. This current EO raises the quantified threshold of economic impact (costs, benefits, or transfer payments) in a given year for “economically significant” (ES) rules from $100 million to $200 million and further directs OIRA to adjust that level for inflation every three years. ES rules face a more rigorous review process under EO 12866 and 13563. As such, the stated purpose of this change is to limit the number of rulemakings with that designation so as “to enable OIRA and agencies to prioritize their analytical resources more effectively.”

Greater Emphasis on Equity Considerations

Section 2 of the EO, entitled “Affirmative Promotion of Inclusive Regulatory Policy and Public Participation,” directs agencies to adopt a series of practices “to promote equitable and meaningful participation by a range of interested or affected parties, including underserved communities.” The most meaningful changes here involve: A) how agencies solicit initial input from such communities and B) how OIRA schedules and conducts meetings with relevant stakeholders on a given rulemaking under review (so-called “EO 12866 meetings”).

Regarding the first point, the Biden Administration is directing agencies both to take a more proactive approach in engaging with relevant communities and to build out a more robust regulatory petition system so that agencies can passively solicit further input from interested parties. The OIRA memo specifically points to the times when an agency is developing its latest “Unified Agenda of Regulatory and Deregulatory Actions” (Unified Agenda) entry “to proactively engage with a broad and diverse set of individuals and organizations” in the development of the Unified Agenda. In terms of building out an ongoing input stream, OIRA directs agencies to explore ways in which they can expand their capabilities to receive and consider petitions for rulemaking, such as online portals.

The proposed changes to the 12866 meeting guidelines are even more detailed – taking up an entire implementation memo of their own. Broadly speaking, these reforms are meant “to reduce the risk or the appearance of disparate and undue influence on regulatory development.” Some of the main specific operational changes include:

- Prioritizing the scheduling of “who have not previously participated in the E.O. 12866 meeting process within the last three years”;

- Limiting each “meeting requester” to “a single E.O. 12866 review of the same regulatory action at the same stage of the regulatory process”;

- Further utilizing so-called “consolidated meetings” in which “groups that would like to present similar views on a regulatory action” can all participate in a single meeting; and

- Including further details in OIRA’s 12866 meeting database on such items as content discussed and participant affiliation.

OIRA is soliciting further comment from interested parties on these meetings changes through June 6, 2023.

Updated Regulatory Analysis Guidelines

The final section of the EO involves an update on how agencies conduct their regulatory analyses. The main item on this front is updating Circular A-4, the government-wide standing memo “designed to assist analysts in the regulatory agencies by defining good regulatory analysis … and standardizing the way benefits and costs of Federal regulatory actions are measured and reported.” OIRA’s newly proposed Circular A-4 marks the first significant update to the document in roughly two decades. The new Circular A-4 covers a plethora of technical considerations agencies need to undertake in producing a regulatory analysis, but the primary changes from its predecessor involve: A) a greater focus on conducting “distributional analysis,” and B) a change to how agencies should discount costs and benefits across a given time horizon.

Per the new Circular A-4, analyzing the “distribution effect” of a regulation involves examining “the impact of a regulatory action across the population and economy, divided up in various ways (e.g., income groups, race or ethnicity, sex, gender, sexual orientation, disability, occupation, or geography; or relevant categories for firms, including firm size and industrial sector).” While, as noted in the document’s preamble, OIRA is not currently seeking to “call for agencies to generally produce distributional analyses in regulatory impact analyses,” it does recommend agencies at least give it greater consideration. To that end, the new Circular A-4 expands what is currently two paragraphs of direction on “Distributional Effects” to nearly four pages of guidelines that walk agencies through the step-by-step process of producing such an analysis.

The other major substantive shift in how agencies conduct a regulatory analysis going forward involves the “discount rate” they should use in projecting costs and benefits into the future. According to the preamble, a discount rate “is the amount by which the future valuation must be adjusted to be expressed in present value terms.” In the example OIRA gives: “if the annual discount rate is a fixed 5%, $100 a year from now is valued equivalently to about $95.24 today ($100/(1 + 0.05)).”

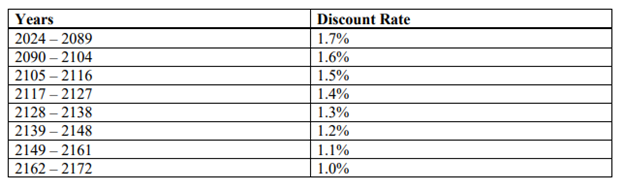

The 2003 Circular A-4 directed agencies to primarily use discounts rates of 3 percent (the “social rate of time preference”) and 7 percent (“the average rate of return to capital”). Noting that “the academic literature and financial markets have evolved significantly since the 2003 guidance,” OIRA now proposes that agencies should primarily use an updated “social rate of time preference” of 1.7 percent and only further consider capital effects on discounting “[w]here substantial incidence on capital is anticipated.” Additionally, the new Circular A-4 contemplates agencies utilizing even lower discount rates for actions they expect to have intergenerational effects (for issues such as climate change) much further into the future, including the following suggested schedule of rates:

As with the memo on 12866 meetings, interested parties have until June 6, 2023, to submit comment on the proposed Circular A-4. OIRA will also be convening a panel of experts to conduct a peer review of the document.

As with the memo on 12866 meetings, interested parties have until June 6, 2023, to submit comment on the proposed Circular A-4. OIRA will also be convening a panel of experts to conduct a peer review of the document.

POTENTIAL ISSUES AHEAD

While many of the changes in the document seem rather dry and technical, their potential impact should not be understated. Take, for example, the ES rule threshold adjustment. OIRA Administrator Richard Revesz noted during a discussion of the EO on April 11 that the new $200 million threshold is justifiable in that it roughly equates to $100 million in 1993 dollars, when EO 12866 established the $100 million level as government-wide policy. There are already some worrisome signs in the implementation of this provision, however.

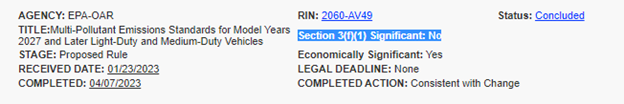

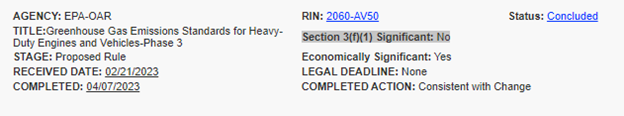

For instance, a pair of Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) rulemakings on vehicle emissions recently concluded review at OIRA:

Pre-publication versions of each proposal confirm that, given how most of the annualized costs and benefit estimates number in the billions of dollars, these rulemakings should easily surpass the $200 million threshold. At this point, however, it at least appears that OIRA does not recognize them as such. The increase in the threshold may have merit on a conceptual basis, but if OIRA is not going to even apply it to the regulations it should, that brings into question how seriously it takes the exercise of reviewing ES rules now.

With regard to the adjustments in meeting protocol, it is difficult to discern at this point what effect it may have on the overall flow or designation of rules. One can foresee, however, a situation where the good intentions of making the process “more equitable” come into tension with the practical concerns of constraining the free flow of information and discussion as agencies and OIRA craft a given rule. On one hand, limiting repetitive meetings may prove somewhat helpful, but for many significant rules, the technical nature of various minute aspects may require precise input from relevant stakeholders across multiple sessions. Arbitrarily limiting this often key OIRA-to-stakeholder exchange of information could lead to certain issues going unresolved or unaddressed.

Another main area of concern – this time on a more conceptual basis – is the change in discount rates. Both the updated Circular A-4 itself and the accompanying preamble cite a prodigious amount of economic literature in support of the decision to primarily use a rate of 1.7 percent. One imagines that this will be among the key debates during the Circular A-4 comment period. This analysis withholds comment for now on the substantive claims cited in these documents, but rather seeks to illustrate the potential implications of a significantly lower discount rate.

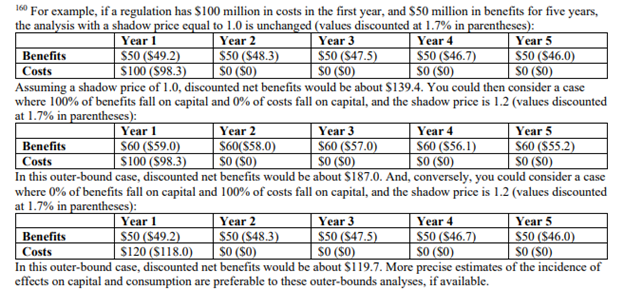

In the discussion of how to approach capital considerations, OIRA includes the following example:

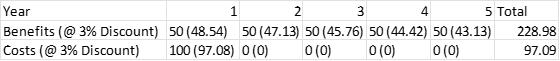

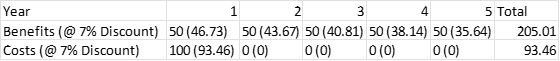

Conducting a similar hypothetical using the previous rates of 3 and 7 percent yield the following results:

Conducting a similar hypothetical using the previous rates of 3 and 7 percent yield the following results:

The total net benefits for each example are $131.9 million and $111.55 million, respectively. These represent respective decreases from the net benefits realized in the primary 1.7 percent rate example used by OIRA ($139.4 million) of $7.5 million and $27.8 million. Granted, the magnitudes of difference here are relatively limited given the exercise’s modest assumptions. Nevertheless, the directional changes are present and measurable.

The total net benefits for each example are $131.9 million and $111.55 million, respectively. These represent respective decreases from the net benefits realized in the primary 1.7 percent rate example used by OIRA ($139.4 million) of $7.5 million and $27.8 million. Granted, the magnitudes of difference here are relatively limited given the exercise’s modest assumptions. Nevertheless, the directional changes are present and measurable.

In the not-uncommon scenario of a regulatory action calling for substantial upfront costs to achieve ongoing benefits, a lower discount rate will naturally raise net-benefits since benefits in the out-years will involve an increasingly diminished discount effect. Whatever the academic justification for this, in scenarios like these, the practical effect will be that agencies will have greater leeway in potentially justifying more stringent – and thus, more costly – options in their rulemaking development. In cases where the effects measure in the billions, there are massive upfront capital-based costs, and benefits are expected to accrue over decades (e.g., the aforementioned EPA rulemakings) such a dynamic would be even more pronounced.

CONCLUSION

The proposed changes to the rulemaking process released last week represent the tangible product of regulatory principles established by the Biden Administration on Day One. Such adjustments will significantly reframe the regulatory process in a way that, perhaps unsurprisingly, focuses more on the benefits side of the ledger. This EO, however, is still a work in progress and the culmination of these actions is still likely a year out. One hopes that careful consideration of input from interested parties will, at the very least, help iron out some of the potential flaws of these reforms.