Insight

July 17, 2025

Scrutiny of Charter and Cox Merger Must Recognize Industry Dynamics

Executive Summary

- On May 16, Charter Communications announced plans to acquire Cox Communications in a $34.5 billion deal that would create the largest cable and broadband provider in the United States.

- The deal could receive regulatory scrutiny from both the Federal Communications Commission and the Department of Justice despite a lack of geographic overlap between the two companies’ cable footprint.

- Any regulatory review of the merger should resist the impulse to artificially narrow the market to cable and broadband and instead rely on the effects the merger would have on consumers, with particular consideration of the influx of new technologies that provide video, programming, broadband, and mobile services.

Introduction

On May 16, Charter Communications announced plans to acquire rival cable provider Cox Communications, a deal valued at $34.5 billion. The merger would create the largest cable and broadband provider in the United States, and while there is little geographic overlap between the companies’ operations, the deal will likely invite regulatory scrutiny from the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) and Department of Justice (DOJ).

The deal accentuates the rapidly evolving competitive landscape in communications services. Cable companies, which once had government-granted monopolies to provide higher-quality internet services over coaxial cable, have been met with – and in some cases surpassed by – increased competition from fiber, satellite, fixed wireless, and mobile broadband services. Cable-provided video services – once the industry’s sole offering – have continued to lose market share as customers “cut the cord” and migrate to streaming services and other digital alternatives

Any regulatory review of the merger should resist the urge to artificially narrow the market to cable and broadband and instead rely on the effects the merger will have on consumers, with particular consideration of the influx of new technologies that provide video, programming, broadband, and mobile services. Indeed, regulators are likely to find that the merger could provide additional competition in other markets the current administration has expressed concerns with, such as mobile broadband and big tech’s streaming services.

Background on Charter and Cox

Charter and Cox provide internet, video, mobile lines, and voice services. The delivery of these technologies has undergone significant change in recent years and has seen the introduction of new rivals.

Broadband Services

While the various lines of business of the two firms overlap, they can hardly be considered rivals. Data from the FCC measuring residential fixed broadband via cable show little geographic overlap between the two firms. Charter’s coverage is largely concentrated in the Northeast, Midwest, Southern California, Central Florida, the Carolinas, and West Texas. Cox operates in small sections of a few select states including Virginia, Massachusetts, Georgia, Louisiana, Kansas, Oklahoma, Nevada, Arizona, and California.

Residential Fixed Broadband Via Cable

*Source: FCC National Broadband Map, Data as of December 31, 2024. Fixed Broadband, Cable

Residential Fixed Broadband via Fiber to the Premises

*Source: FCC National Broadband Map, Data as of December 31, 2024. Fixed Broadband, Fiber to Premises

Further, cable broadband is only one of many fixed broadband services. In recent years, fiber-to-the-home, fixed wireless access, and low-earth orbital satellites have all begun to take market share away from cable providers.

Video Services: The Path to Cord-cutting and Unbundling

Technological advancements in telecommunications have lowered barriers to entry for delivering video content to consumers, ushering in a flood of new video service providers. This deluge of new competitors has led consumers to cancel their cable video services in a trend called “cord-cutting,” and instead only purchase broadband internet services. This allowed consumers to migrate toward an unbundled model in which they purchased video services offered by digital platforms that operate over the internet rather than as a bundle with both cable video and broadband.

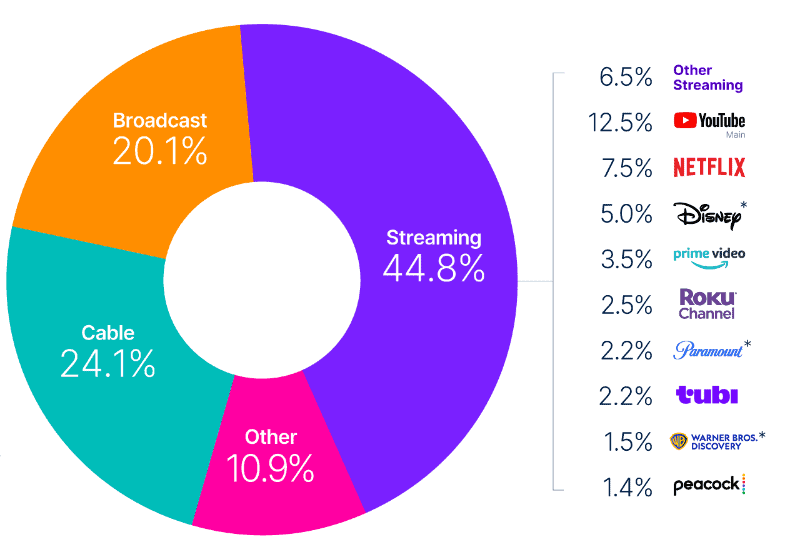

As a result, digital platforms such as Hulu, YouTube, and Disney+ have largely unseated cable companies as the dominant form of video services in the same way cable had previously ousted local broadcasters. According to Nielsen, a media data and analytics firm best known for audience measurement, streaming’s share of total television usage surpassed the combined share of broadcast and cable for the first time in May 2025.

*Source: Nielsen; Streaming Reaches Historic TV Milestone, Eclipses Combined Broadcast and Cable Viewing For First Time

Nielsen also reported that since its monthly publication that tracked streaming debuted in 2021, streaming usage has increased 71 percent. Moreover, the original list of platforms that “exceed a full share point of TV usage” expanded to 11 platforms from five.

The recent trend in cord-cutting and unbundling has left the traditional cable and broadband industry unrecognizable from 15 years ago. Between 2010 and 2024, cable subscriptions have dropped from 105 million to just under 69 million as consumers purchase the specific video subscriptions they want and avoid paying for unwanted channels that come with cable video.

Mobile Services

The mobile market, similarly, has undergone a change in market dynamics that includes increased competition from traditionally fixed providers. Mobile providers such as AT&T, Verizon, and T-Mobile still lead the market as they provide the only facilities-based 5G services – where the mobile network operators own and manage their own infrastructure –at a nationwide level.

Cable companies, however, have invested in their own mobile networks and partner with industry leaders in areas where they lack deployment. These Mobile Virtual Network Operators (MVNO) apply competitive pressure on the mobile networks to improve services and lower costs, especially as they are typically bundled with fixed-home internet services.

This evolution has blurred the boundaries between mobile and fixed services. Mobile services have increased bandwidth and lowered costs. Consumer demand for mobility – whether it be moving around the house, building, or even over a wider range without losing connection – has forced the industry to develop fixed networks via local Wi-Fi. As these markets continue to converge, consumers will benefit from the added competition.

The Impetus for the Acquisition

The morphing communications services landscape has left cable companies – including Charter and Cox – with increased competition from nontraditional technologies to provide video, broadband, programming, and mobile services. Charter’s acquisition of Cox will enable the firm to boost investment in its existing fixed network that expands its coverage to include communities that either lack broadband coverage or have a dearth of competition.

Furthermore, the acquisition will allow the two firms to combine spectrum assets, particularly in the citizen’s broadcast radio service (CBRS) band to build out their mobile network infrastructure. Currently, both Charter and Cox have licenses to operate in the CBRS band and are providing MVNO services to their customers, but building out these networks is expensive and risky. As a result, both firms pay large mobile broadband providers for access to their networks. The merged firms can better develop a business case for mobile buildout – particularly in large cities – which over time will see less reliance on existing nationwide mobile networks.

The deal also allows the combined firms to challenge video services as consumers continue to “cut the cord” and cancel their cable video services. By combining video assets, Cox and Charter could increase investment in their video-delivery services and enable them to offer more options to better compete with the ever-expanding digital platforms developed by big tech firms and television networks.

Regulatory Considerations

The combination of Cox and Charter will likely face regulatory scrutiny from the Trump Administration. Both the DOJ and the FCC will review the transaction, each applying a different standard.

The DOJ’s review will primarily be evaluated under Section 7 of the Clayton Act, which prohibits mergers that may substantially lessen competition or tend to create a monopoly. The FCC, meanwhile, is governed by the Communications Act, which imposes a public interest standard for review. Underlying both reviews is the Trump Administration’s concern about market concentration, which increases uncertainty about whether regulators will challenge the deal.

The FCC, which has a broader legal scope to challenge the merger, has been largely favorable to merging companies, so long as the firms agree to a variety of non-competition related conditions, including abandoning diversity, equity, and inclusion initiatives. Assuming the firms capitulate, it seems unlikely the FCC will take action to block the merger.

The Trump DOJ, however, has expressed more concern about concentration in telecommunications markets. The 2023 Merger Guidelines – adopted in the previous administration – reflect an approach that is largely hostile to consolidation irrespective of the competitive effects on consumers. The decision by the DOJ and Federal Trade Commission to leave this guideline in place suggests, in part, that they share a similar skepticism of industry consolidation. Yet the DOJ may be more inclined to permit the deal as it has expressed concerns about a lack of competition in mobile markets, especially after the failure of EchoStar to build out a fourth nationwide network as agreed to in the Sprint/T-Mobile deal. If the DOJ indeed seeks to foster competition in the mobile networks market, approving the deal could inject the type of competitive pressure that a fourth nationwide network would have offered, especially if the combined firm can expand its network into major markets and increase the amount of traffic offloaded from mobile networks.

Further, both the FCC and DOJ have expressed concerns about the power of large technology firms. Many of the big tech firms offer video content directly to consumers, which has led to the cord-cutting trend. The combined video assets of Charter and Cox could bolster the competition faced by big tech in the video marketplace, which could align with regulators’ competition priorities.

The lack of geographic overlap between Cox and Charter – one of the components of a market definition – and the competitive threats that continue to emerge and, in some cases, overtake traditional cable and broadband, should give the antitrust agencies pause before attempting to block the merger.

Conclusion

While the Trump Administration has expressed concerns about market concentration, the Charter/Cox deal highlights why narrow views of competition and markets could actually harm the administration’s goals. Even if the Trump Administration wants less concentration in broadband markets, this deal between two firms that do not directly compete would inject more competition into a variety of markets and lower costs for consumers. That said, the deal will likely not be approved without capitulation from Charter on a variety of unrelated businesses practices.