Insight

June 24, 2016

Tax Topics – Interest Deductibility

The Corporate Tax Code Favors Debt

Under current law, when a corporation files its tax return it can deduct interest on debt as a business expense, just like employee salaries, rent on office space and paper clips. With interest on debt taken out of the tax base through deductibility, returns to debt-financed investment face a much lower tax rate. Indeed, debt financing capital purchases generates a marginal effective tax rate of -2.2 percent, compared to 39.7 percent on equity financing, according to a study from the Department of the Treasury.[1]

Consider a business that needs to raise $1 billion to finance a new project. The business could issue debt or sell stock to pay for the new venture. If it finances the investment through debt, its interest payments to holders of its debt are tax deductible, while its returns to its shareholders are not, hence the large tax disparity. Such a large tax preference for debt over equity introduces large distortions in how firms finance investment and encourages business to take on greater leverage than they otherwise would.

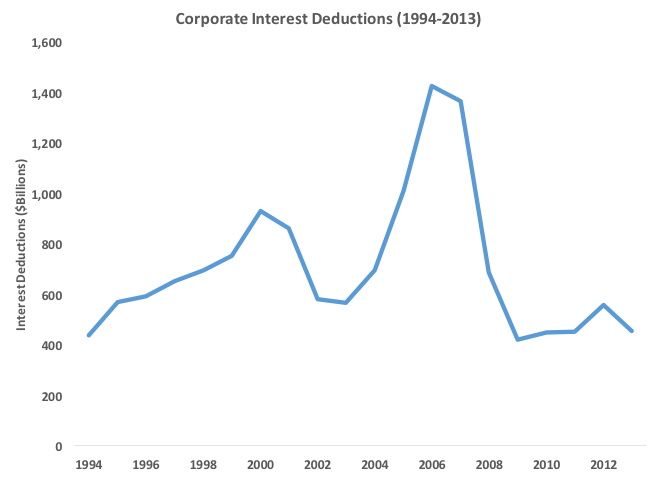

Corporations with net income claimed $455 billion in tax deductions for interest paid in 2013.[2] For context, in 2007 corporations claimed nearly $1.4 trillion in interest deductions. While certainly not the cause of the financial crisis, overleveraging by firms made the recession worse, and would suggest that a tax subsidy to leverage is worth reconsidering.

Options for Reform

Reform of this tax subsidy should be viewed as how best to achieve neutrality in corporate finance decisions – essentially taking the tax code out of the decision. This can be done be raising the effective tax on debt financing or lowering the effective rate on equity investment – and it can occur within the current system or as part of a much broader tax reform.

The first option for addressing the tax bias in favor of debt would be to achieve neutrality in the context of the current tax code. Under the current tax system, interest income is fully taxable at the individual level while dividends are taxed at preferential rates. Equalizing this treatment would this require individual income tax changes as well. This effort could include eliminating interest deductibility and taxing it at a preferential rate at the individual level, or allowing corporations to deduct dividends and equalize the treatment of interest and dividend income at the individual level.

A more comprehensive, pro-growth tax reform would also reform the system of capital cost recovery. Unlike other business expenses (such as wages) capital investment is not fully deducted when it occurs. Instead, it must be depreciated– meaning that a portion of the cost of the investment is deducted each year; incrementally over time the cost of the investment is recovered. The pace of capital cost recovery is based on the type of investment made.

But a dollar in the future is worth less than a dollar to day – inflation and the time value of money erode the value of future tax write-offs for investment. Indeed, for a $1-dollar investment in an office building that must be depreciated over 39 years, the value of the tax deduction diminishes to 37 cents.[3]

A pro-growth reform that moved to a business cash flow approach would allow for an immediate deduction of the full cost of the investment. So a $1-dollar investment could be fully deducted from taxable income in the year in which the investment would be made – reducing the effective tax rate on that investment to zero. This is would essentially remove tax barriers to new investment decisions and spur economic growth.[4]

A reform that moved to full expensing would require the elimination of interest deductibility to preserve neutrality. While the current tax system favors debt financed investment over equity, a reform that included full expensing and preserved interest deductibility would introduce a massive subsidy to debt financing.[5] According to the Congressional Budget Office, the effective tax rate on debt-financed investment would drop to -61 percent.

The goal of tax reform should be to enhance economic growth and, as a complement, eliminate or mitigate distortions imposed by the tax code. Moving to a business tax regime that included expensing would achieve both, but only if paired with the elimination of interest deductibility.

[1] https://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/Documents/Report-Improve-Competitiveness-2007.pdf

[2] https://www.irs.gov/uac/soi-tax-stats-table-17-corporation-returns-with-net-income-form-1120

[3] http://mercatus.org/sites/default/files/Fichtner-Corporate-Capital-Cost.pdf

[4] See https://www.aei.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/04/-hassett-testimony-to-jec-april-17-2012_140211541382.pdf; http://taxfoundation.org/blog/economic-and-budgetary-effects-full-expensing-investment

[5] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/113th-congress-2013-2014/reports/49817-Taxing_Capital_Income_0.pdf