Insight

April 21, 2025

The 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act: Revenue Effect and Analysis

Executive Summary

- On April 8, Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) reintroduced the 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act, which would levy tiered and escalating tariffs on selected imported goods based on their carbon emissions; the legislation is aimed at boosting U.S. manufacturers’ competitiveness in low-carbon goods and raise tax revenue.

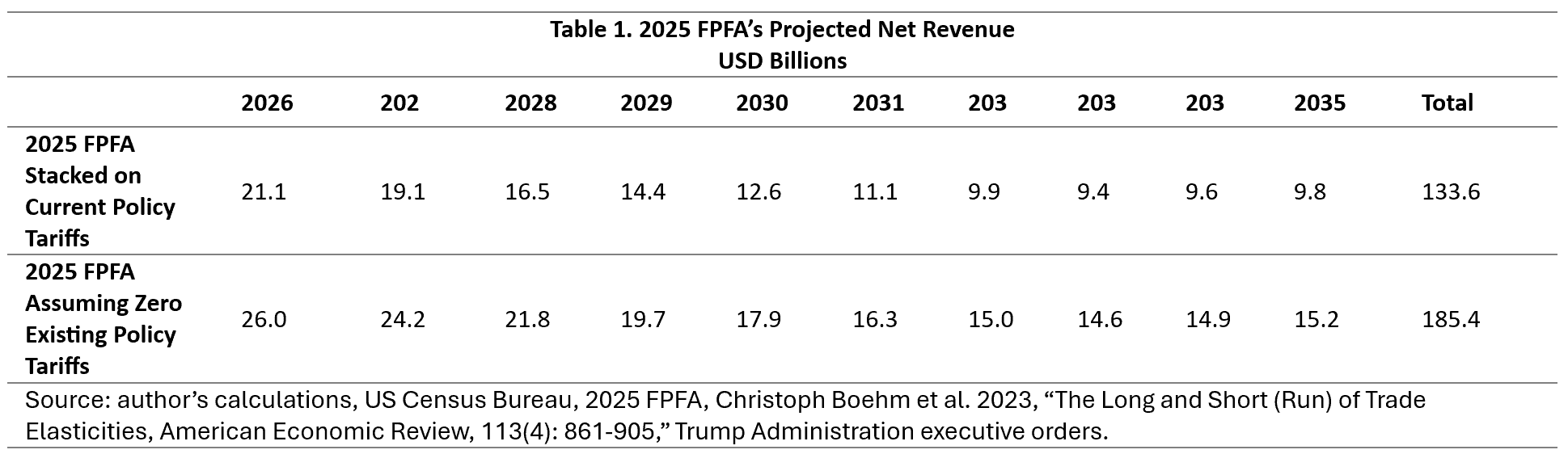

- The tariffs would raise an estimated $133.6 billion from 2026–2035 if it is enacted in addition to current-policy tariffs, and $185.4 billion over the same period if enacted in isolation.

- Top exporting economies affected by the tariffs would include Canada, China, Mexico, Vietnam, India, Taiwan, and Thailand.

Introduction

On April 8, 2025, Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) reintroduced the 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA) , which would levy tiered and escalating tariffs on selected imported goods. The legislation is aimed at boosting U.S. manufacturers’ competitiveness in low-carbon goods and raise tax revenue.

This research finds that these tariffs would raise an estimated $133.6 billion from 2026–2035 if enacted in addition to current-policy tariffs, and $185.4 billion over the same period if enacted in isolation. Top exporting economies affected by the tariffs would include Canada, China, Mexico, Vietnam, India, Taiwan, and Thailand.

The American Action Forum previously released a brief analysis of the legislation. This piece provides an analysis of the revenue effects of the carbon tariff proposal.

Overview and Analysis of the 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act

The FPFA would levy tariffs on eight sectors of imported goods based on their carbon emissions:

- Objective: According to the press release, the legislation is intended to “level the playing field for American manufacturers and workers by holding non-market economies like China accountable for their unfair trade practices.”

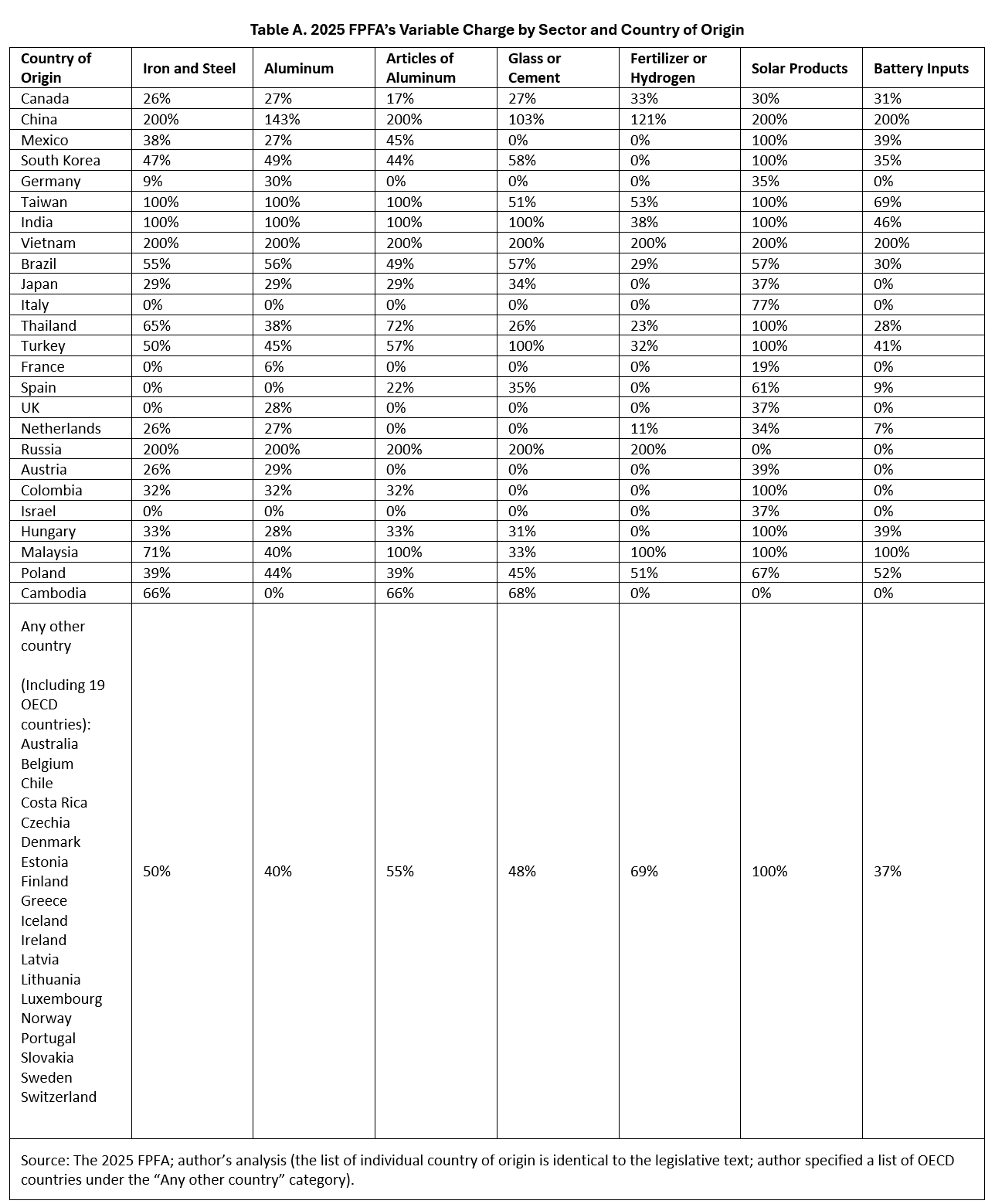

- Tariff Rates: The country- and product-specific tariff rate is a variable rate set in a multi-tiered tariff framework that is applied as a percentage of the custom import value of a good. The FPFA only specifies 25 countries’ tariff rates; the world’s remaining countries, including 19 Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries, are subject to the same set of rates for covered goods. (See Table A in the appendix.) The specified tariff rates are applicable in the initial three years of the FPFA’s implementation, before the variable charges are updated based on the criteria listed in the legislation.

- Tax Base: The proposal covers aluminum, cement, iron and steel, fertilizer, glass, hydrogen, and certain inputs for solar and battery manufacturing.

- Exemptions: The proposal allows exemptions of certain imported goods if they are deemed necessary for national defense purposes, or if the country of origin of the covered goods participates in the “international partnerships” program to levy “interoperable methods to promote pollution reduction through trade mechanisms.”

- Additional Punitive Tariffs: The legislation includes provisions to escalate the tariff rates to double or quadruple the size of the variable charge if the covered goods are imported from a “nonmarket economy country” or manufactured by a “foreign entity of concern.” For example, if a country is considered a “nonmarket economy country,” the tariff rates of the covered iron and steel goods produced by a “foreign entity of concern” in this country would be subject to a multiplier of four.

- Anti-avoidance Measures: The legislation also gives relevant agencies the authority to escalate the tariff rates to a level “deemed necessary to offset or deter such evasion” to discourage foreign producers’ attempts to reroute their exports to avoid paying the tariffs.

The 2025 FPFA would not have a material impact on emissions reduction. This is because the proposal would levy country-specific tariffs across different covered sectors, which would discourage individual foreign producers from lowering their emissions to reduce tariffs on their goods. Additionally, the FPFA does not include any domestic carbon price, and thus there is no incentive for U.S. producers to lower their carbon emissions.

Revenue Estimate

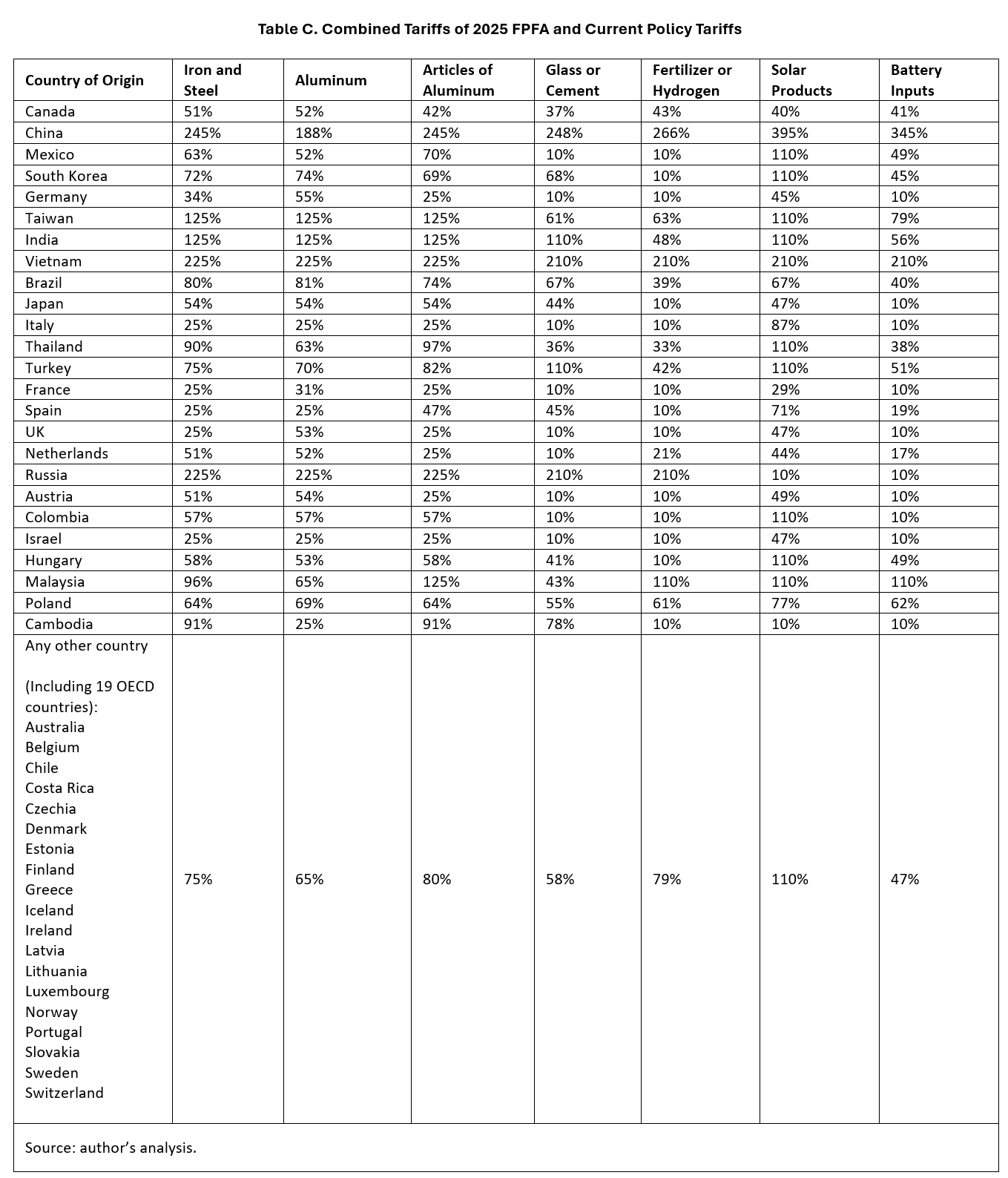

This research finds that – considering the 2025 FPFA’s tax rate, tax base, behavioral responses, the effects of the tariffs on income and payroll tax revenue, and the current policy tariffs (see Table B and Table C in the appendix) – the 2025 FPFA would raise up to $133.6 billion in net revenue from 2026–2035 if the FPFA tariffs are stacked on current-policy tariffs, and $185.4 billion excluding current-policy tariffs.

These are likely upper-bound estimates as they do not account for any potential tariff exemption or reduction for national security purposes or through the International Partnership Agreement, nor do they include any potential foreign retaliation, which would reduce taxable income in the United States.

The FPFA’s high tariff rates would result in a significant reduction in imported goods. The legislation’s imports reduction would be exacerbated if its tariffs are combined with current-policy tariffs. For example, the value of covered FPFA goods from China would drop 87 percent if the FPFA’s tariffs were added to current-policy tariffs.

The United States’ major trading partners, such as Canada, China, Mexico, Vietnam, Thailand, India, and Taiwan are top exporters that account for a relatively large share of the total tariff revenue collected, especially Canada, China, and Mexico. (See Table 2)

Appendix

Source: Section 232 steel and aluminum tariffs; 10-percent baseline tariffs on all countries; China-specific tariffs under Section 301.