Insight

August 8, 2023

The Administrative State After Chevron

Executive Summary

- On June 15, the House of Representatives passed the Separation of Powers Restoration Act of 2023 (SOPRA), which would permit courts to decide de novo questions of statutory interpretation and administrative rulemaking when federal agencies promulgate regulations.

- SOPRA would obviate the decision in Chevron v. NRDC, in which the Supreme Court ruled that courts should defer to agencies’ “reasonable” interpretations of ambiguous statutes.

- Although SOPRA is unlikely to pass the Senate, it brings attention to how Chevron deference enables regulatory overreach – a decades-long trend that could be arrested when the Supreme Court decides Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo next term.

Introduction

On June 15, 2023, the House of Representatives passed the Separation of Powers Restoration Act of 2023 (SOPRA), or H.R. 288, with all but one Republican voting in favor and all but one Democrat voting against passage. The legislation, sponsored by Representative Scott Fitzgerald (R-WI), expands the set of circumstances under which courts can apply judicial review to actions of administrative agencies. In particular, SOPRA would enable courts to decide de novo questions of statutory interpretation and administrative rulemaking when federal agencies promulgate regulations, instead of deferring to the conclusion of any party in the dispute. This includes but is not limited to disputes over how to interpret ambiguous statutory provisions, rules, policy statements, and informal guidance documents.

SOPRA would overturn Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council, in which the Supreme Court ruled that courts should defer to an agency’s “reasonable” interpretation of an ambiguous statute. The bill is unlikely to become law, but it demonstrates that judicial deference has empowered executive agencies to balloon in size and scope and implement more, and more burdensome, regulations. Notwithstanding the Senate’s probable inaction on SOPRA and other bills to curb the regulatory state, the Supreme Court could overturn Chevron next term when it hears arguments in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, a decision that could play an outsized role in reversing the accelerating growth of federal bureaucracy.

Chevron Deference

SOPRA would be a legislative remedy to regulatory bloat, which is a result of excessive acquiescence to executive branch rulemaking, enabled by various types of judicial deference. Foremost among the deference doctrines is Chevron deference, named after the Supreme Court’s 1984 decision in Chevron v. Natural Resources Defense Council. In its unanimous decision, the Court set forth a two-part test to determine whether agencies should be afforded deference in their interpretations of a statute that was enacted by Congress. First, if Congress has clearly addressed the precise question at issue, then the agency must abide by the legislature’s stated interpretation thereof. If, however, the statute does not address the precise question or if its treatment thereof is ambiguous, courts must defer to the agency’s interpretation of the statute provided that its interpretation is “reasonable.”

What meets the thresholds for statutory ambiguity and for reasonability raises more questions than it answers, however, and courts have struggled to determine which agency interpretations pass muster. Moreover, the procedure laid out in Chevron stands in apparent contravention to the Administrative Procedure Act, which instructs courts to “decide all relevant questions of law, interpret constitutional and statutory provisions, and…hold unlawful and set aside agency…conclusions found to be…not in accordance with law; in excess of statutory jurisdiction, authority, or limitations, or short of statutory right.”

SOPRA would legislatively override Chevron v. NRDC, as well as other pro-deference decisions in Skidmore v. Swift & Co., Auer v. Robbins, and Kisor v. Wilkie, which affirmed the validity of judicial deference for agencies’ informal documents and regulations in addition to ambiguous statutory provisions. (See table below.)

Supreme Court Cases That Would Be Overridden by SOPRA

| Case | Year | Implications for judicial deference to agencies |

| Skidmore v. Swift & Co. | 1944 | Courts may defer to an agency’s interpretation of informal documents – though they should typically be less deferential than for statutes or regulation. The degree of deference “depend[s] upon the thoroughness evident in [the agency’s] consideration, the validity of its reasoning, its consistency with earlier and later pronouncements, and all those factors which give it power to persuade.” |

| Chevron U.S.A. Inc. v. Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc., et al. | 1984 | If Congress has not directly addressed a particular question of statutory interpretation or if the statute is silent or ambiguous about such a question, courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation thereof if the interpretation is reasonable – that is, it is “based on a permissible construction of the statute.” |

| Auer et al. v. Robbins et al. | 1997 | Courts should defer to an agency’s interpretation of its own ambiguous regulation unless the interpretation is “plainly erroneous or inconsistent with the regulation.” |

| Kisor v. Wilkie, Secretary of Veterans Affairs | 2019 | Auer and Seminole Rock, its 1945 forerunner, are not overruled. But Auer deference has a limited scope and should not be applied in all circumstances. Judicial deference to administrative agencies is justified after courts exhaust traditional tools of construction, the rule in question is truly ambiguous, the interpretation is reasonable, and “the character and context of the agency interpretation entitles it to controlling weight” – that is, the interpretation should reflect the agency’s authoritative or official (rather than ad hoc) position, must implicate the agency’s substantive expertise, and must reflect the agency’s “fair and considered judgment.” |

“A Tombstone No One Can Miss”

Chevron deference has ramifications for the separation of powers, legislative compromise, and regulatory expansion.

First, the American constitutional order is founded on Congress producing legislation in service of the national interest and the executive swiftly and appropriately administering the resulting law. Administrative agencies should avoid veering away from Congress’ intentions as much as practicable. Chevron deference flips this framework on its head. Agencies ask not what Congress has clearly authorized them to do, but what interpretations of statutes could achieve deference and elude courts’ scrutiny. As then-Judge Brett Kavanaugh explained, everything, “unless it is clearly forbidden,” becomes fair game. Agencies risk seizing powers properly understood to belong to the legislative branch, and Chevron deference limits judicial remedies. As Justice Clarence Thomas has noted, Chevron conflates Congress’ neglect to meticulously spell out the precise statutory bounds of an agency’s mandate with an affirmative delegation of expansive authority to the bureaucracy. Chevron deference has allowed the executive to arrogate power from the legislative branch because it enables agencies to unilaterally enact policy, often without regard for Congress’ original intent in crafting legislation. By interpreting ambiguous statutes for the purpose of formulating policy, executive agencies may be unconstitutionally usurping Article I legislative powers.

Second, Chevron deference has proven deleterious to legislative compromise, especially across partisan lines. The comparative ease of agency rulemaking has discouraged compromise because it gives legislators an easy out: implementing preferred policy without going through the hard yards of negotiation with colleagues. As former Solicitor General Paul Clement put it, “half the people in Congress can get their friends in the executive branch to do what they want just through an administrative rule. So why compromise? If you can get the immediate objective through an administrative rule, why compromise for a long-term solution that’s in legislation?”

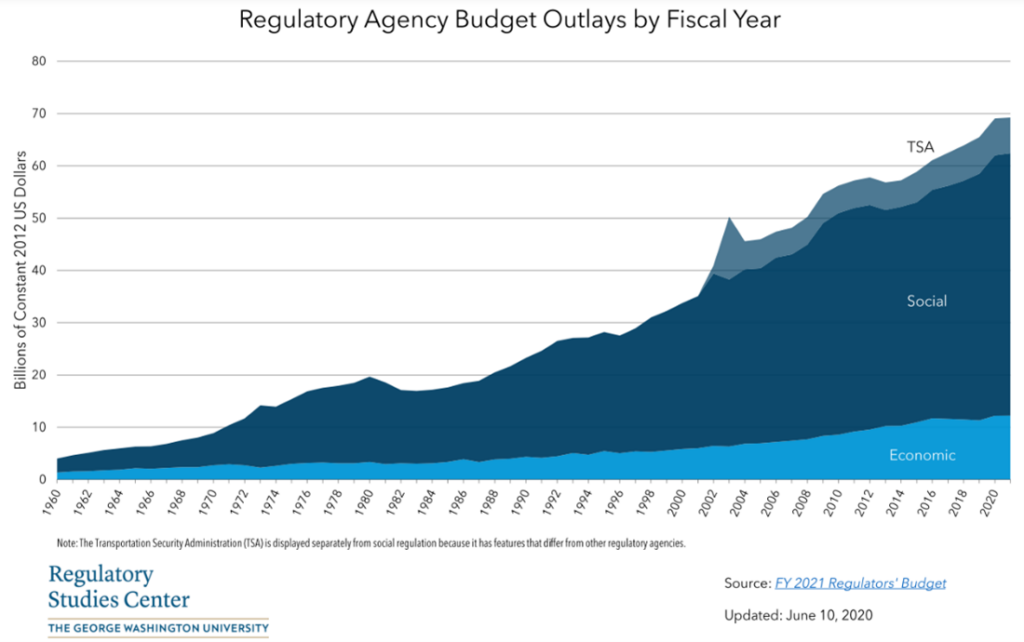

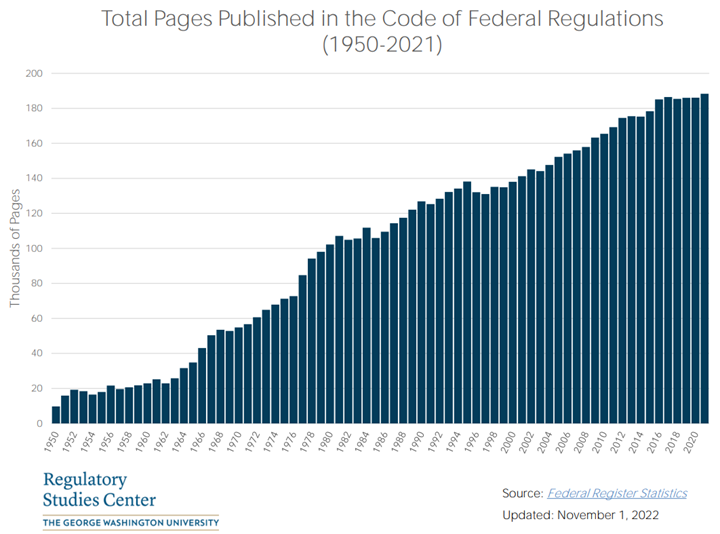

Third, Chevron has enabled the vast expansion of the regulatory bureaucracy. Especially since the 1980s, both the number of federal regulations and the expenditures attributed to regulatory agencies have grown significantly. (See graphs below.)

Judicial deference to the administrative state has abetted this trend. Justice Neil Gorsuch has lambasted deference doctrines for creating “systematic judicial bias in favor of the federal government, the most powerful of parties, and against everyone else.” By giving agencies the final word over how to interpret various statutes, rules, documentation, and guidance, it is difficult for stakeholders affected by their regulations to mount successful legal challenges. As a result, agencies are empowered to reach beyond their statutory mandate and are likely to promulgate more rules.

Judicial deference to the administrative state has abetted this trend. Justice Neil Gorsuch has lambasted deference doctrines for creating “systematic judicial bias in favor of the federal government, the most powerful of parties, and against everyone else.” By giving agencies the final word over how to interpret various statutes, rules, documentation, and guidance, it is difficult for stakeholders affected by their regulations to mount successful legal challenges. As a result, agencies are empowered to reach beyond their statutory mandate and are likely to promulgate more rules.

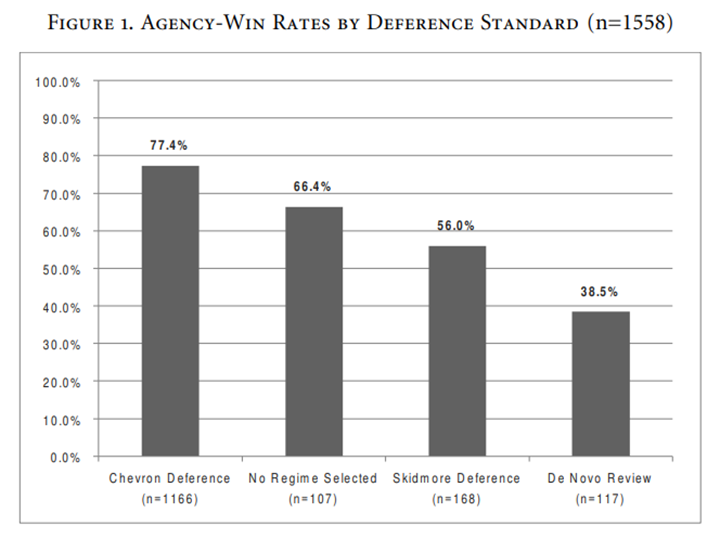

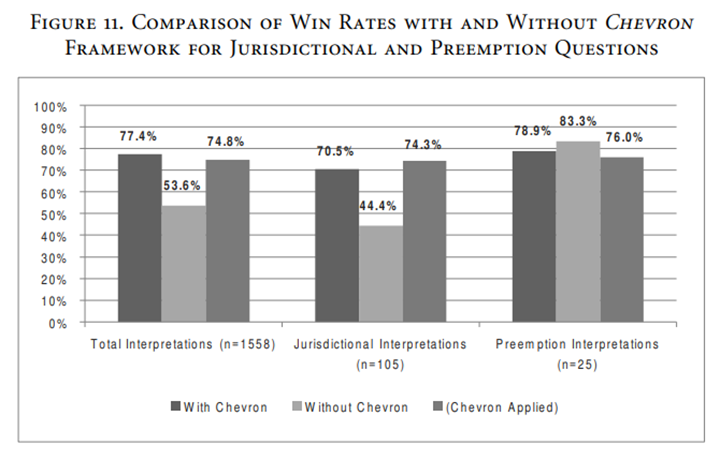

Although the Supreme Court has avoided using Chevron deference in recent years – perhaps signaling unease with the doctrine – a majority of federal appellate court judges continue to faithfully apply Chevron as a binding precedent of the high court. Research indicates that circuit courts frequently use the doctrine to uphold interpretations of ambiguous statutes, invoking Chevron 74.8 percent of the time in such cases, with an agency win rate of 77.4 percent. This exceeds the agency win rate when the court declines to invoke any deference doctrine, utilizes Skidmore deference, or applies de novo judicial review. Moreover, there is a 23.8 percentage point increase in the agency win rate when Chevron is applied compared to when it is not. (See graphs below.)

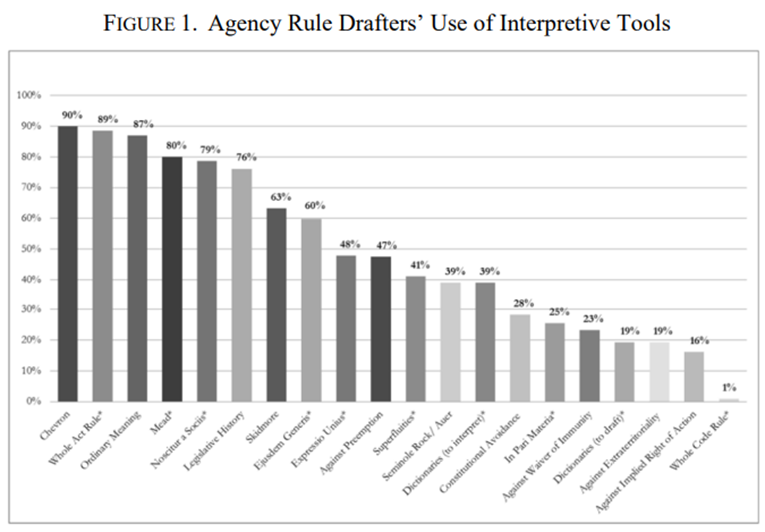

Bureaucrats and administrators within the executive branch recognize these facts and trends. A 195-question survey of 128 rule drafters representing seven federal departments and two independent agencies found that Chevron deference was the most well-known interpretive tool of the 22 included in the questionnaire and was recognized by 94 percent of respondents. Furthermore, 90 percent of the agency rule drafters reported that Chevron plays a significant role in formulating regulations – a figure that outstrips the percentages for other forms of deference (such as Skidmore and Auer/Seminole Rock), canons of statutory construction (such as the whole act rule, ordinary meaning, and noscitur a sociis), and other legal norms and presumptions. (See graph below.)

Bureaucrats and administrators within the executive branch recognize these facts and trends. A 195-question survey of 128 rule drafters representing seven federal departments and two independent agencies found that Chevron deference was the most well-known interpretive tool of the 22 included in the questionnaire and was recognized by 94 percent of respondents. Furthermore, 90 percent of the agency rule drafters reported that Chevron plays a significant role in formulating regulations – a figure that outstrips the percentages for other forms of deference (such as Skidmore and Auer/Seminole Rock), canons of statutory construction (such as the whole act rule, ordinary meaning, and noscitur a sociis), and other legal norms and presumptions. (See graph below.) The data show that deference to federal agencies remains one of the most significant facets of administrative law, and burdens businesses and individuals with hefty regulatory costs. A wealth of research shows that federal regulatory accumulation encumbers small businesses, slows economic growth, distorts markets, increases prices for consumers, and has a disproportionate impact on the poor. A Mercatus Institute working paper analyzed the cumulative effects of regulations and found that regulatory expansion since 1980 slowed economic growth by 0.8 percentage points annually, causing the U.S. economy to be $4 trillion smaller in 2012 than it otherwise would have been. Another study concluded, “Federal regulations added over the past 50 years have reduced real output growth by about 2 percentage points on average over the period 1949–2005. That reduction in the growth rate has led to an accumulated reduction in GDP of about $38.8 trillion [about $277,100 per household] as of the end of 2011.” These ramifications are especially concerning given the Biden Administration’s regulatory spree. From January 20, 2021, to July 28, 2023, the administration has finalized 620 rules with an aggregate cost of $395.5 billion and 232.4 million paperwork hours according to data from the American Action Forum. It is easy to see why Justice Gorsuch remarked that Chevron “deserves a tombstone no one can miss.”

The data show that deference to federal agencies remains one of the most significant facets of administrative law, and burdens businesses and individuals with hefty regulatory costs. A wealth of research shows that federal regulatory accumulation encumbers small businesses, slows economic growth, distorts markets, increases prices for consumers, and has a disproportionate impact on the poor. A Mercatus Institute working paper analyzed the cumulative effects of regulations and found that regulatory expansion since 1980 slowed economic growth by 0.8 percentage points annually, causing the U.S. economy to be $4 trillion smaller in 2012 than it otherwise would have been. Another study concluded, “Federal regulations added over the past 50 years have reduced real output growth by about 2 percentage points on average over the period 1949–2005. That reduction in the growth rate has led to an accumulated reduction in GDP of about $38.8 trillion [about $277,100 per household] as of the end of 2011.” These ramifications are especially concerning given the Biden Administration’s regulatory spree. From January 20, 2021, to July 28, 2023, the administration has finalized 620 rules with an aggregate cost of $395.5 billion and 232.4 million paperwork hours according to data from the American Action Forum. It is easy to see why Justice Gorsuch remarked that Chevron “deserves a tombstone no one can miss.”

“Chevron Step Zero” and the Major Questions Doctrine

Michigan Law Professor Christopher J. Walker has argued that the very legal doctrine of Chevron has morphed and become more context specific, varying in application by the issue in question. He points to Chief Justice John Roberts’ dissent in City of Arlington v. FCC, as well as his majority opinion in King v. Burwell, wherein the court declined to defer to the Internal Revenue Service’s interpretation of a statutory phrase. The Court still upheld the IRS rule in question – which concerns tax credits to federal exchanges under the Affordable Care Act – as a permissible exercise of the agency’s authority. In so doing, the Court added a so-called “Chevron Step Zero” – an inquiry into whether the facts of the case justify applying the doctrine’s two-step test in the first place. As Chief Justice Roberts noted in King v. Burwell, Chevron ought to be applied to major questions – those of “deep ‘economic and political significance’” – only in cases in which a court can ascertain clear congressional intent to delegate the relevant power to the agency. By “ground[ing] his major questions doctrine as a threshold, Step Zero inquiry,” the Chief Justice transformed Chevron’s purview from its relatively broad origins to a doctrine whose applicability varies according to the context.

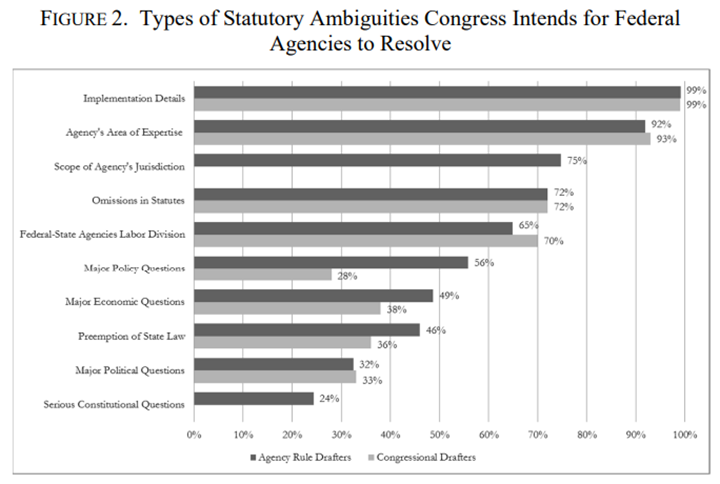

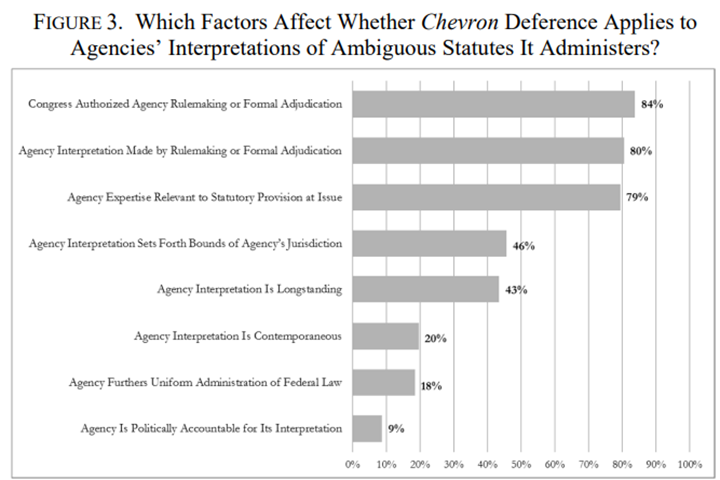

As a result, not all disputes about statutory interpretation are treated equally in the courts or by the bureaucracy. Data from the aforementioned survey of more than 100 agency rule drafters show that a vast majority believe that federal agencies have the prerogative to resolve statutory ambiguities relating to implementation details (99 percent), the agency’s substantive expertise (92 percent), the scope of the agency’s jurisdiction (75 percent), omissions in statutes (72 percent), and the division of labor between federal and state agencies (65 percent). By contrast, a markedly lower proportion of respondents expressed the belief that agencies were empowered to address major policy (56 percent), economic (49 percent), political (32 percent), or constitutional (24 percent) questions. Moreover, a vast majority of agency rule drafters believe that whether Chevron applies depends on whether Congress has authorized rulemaking or formal adjudication (84 percent), whether the agency interpretation is made by rulemaking or formal adjudication (80 percent), and whether the agency has issue expertise that implicates the statutory provision (79 percent). (See graphs below.)

The major questions doctrine has become especially pertinent in recent years. With the decision in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency – its most potent and forthright defense of the doctrine yet – the Supreme Court has signaled its willingness to cabin the administrative state by determining whether Congress has clearly authorized agencies to pursue sweeping regulations regarding matters of vast significance. Regardless of whether the utilization of the major questions doctrine should be seen as a harbinger of the outright end of Chevron or rather as an exception by which the court incrementally chips away at deference, it is a noteworthy development.

The major questions doctrine has become especially pertinent in recent years. With the decision in West Virginia v. Environmental Protection Agency – its most potent and forthright defense of the doctrine yet – the Supreme Court has signaled its willingness to cabin the administrative state by determining whether Congress has clearly authorized agencies to pursue sweeping regulations regarding matters of vast significance. Regardless of whether the utilization of the major questions doctrine should be seen as a harbinger of the outright end of Chevron or rather as an exception by which the court incrementally chips away at deference, it is a noteworthy development.

Which Parts of the Administrative State Are Most Likely To Be Affected?

It would be difficult to overstate what effect the circumscription or end of Chevron deference would have on the size and powers of the regulatory state. It is likely, however, that agencies would take greater pains to act in accordance with the powers Congress explicitly delegates to them, rather than straying beyond that territory when ambiguity arises. Yet if the courts were required to decide relevant questions de novo, instead of deferring to agencies, such a development would have uneven consequences across the regulatory landscape. It is likely that regulatory bloat in certain issue areas and promulgated by certain executive agencies would be at greater risk of critical judicial review than regulations in other areas and promulgated by other agencies.

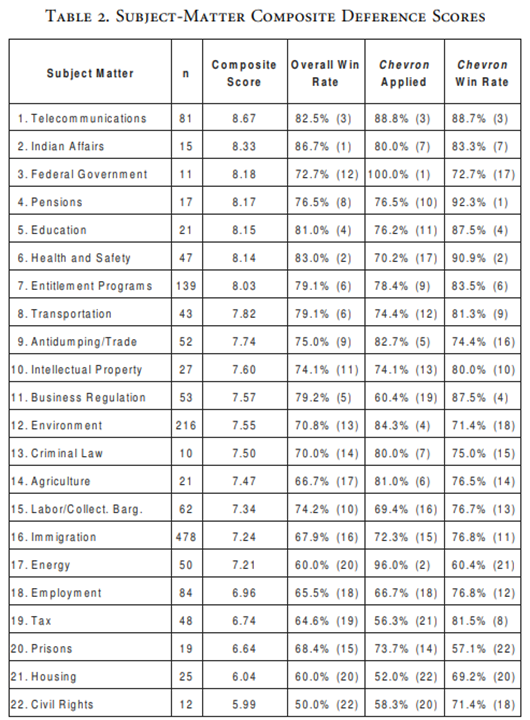

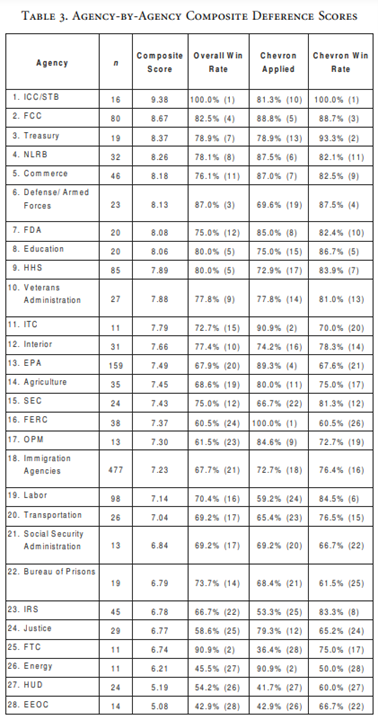

Two tables from a study by administrative law scholars Kent Barnett and Christopher J. Walker are reproduced below. The figures therein are based on a review of relevant federal court cases and reflect the average of three statistics: the agency’s overall win rate, the rate at which Chevron deference was applied as a proportion of the total number of cases in the dataset, and the agency’s win rate conditional on Chevron being applied. The resultant figure was subsequently normalized onto a zero-to-10 scale, with larger numbers indicating a higher frequency of agencies being afforded deference. The first table disaggregates the data by substantive issue area, and the second by agency.

Federal courts have been the most deferential to agencies when the subject matter at issue relates to telecommunications, followed by Indian affairs, the federal government, pensions, education, health and safety, and entitlements. The issue area in which agencies have been afforded the least deference is civil rights, followed by housing, prisons, tax, employment, energy, and immigration.

Federal courts have been the most deferential to agencies when the subject matter at issue relates to telecommunications, followed by Indian affairs, the federal government, pensions, education, health and safety, and entitlements. The issue area in which agencies have been afforded the least deference is civil rights, followed by housing, prisons, tax, employment, energy, and immigration.

The analogous data for agencies show that the agencies afforded the most deference were the Surface Transportation Board (STB), Federal Communications Commission (FCC), Department of the Treasury, National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), Department of Commerce, Department of Defense, Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and Department of Education. The Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) had the lowest rate of deference, followed by the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), Department of Energy, Federal Trade Commission (FTC), Department of Justice, Internal Revenue Service (IRS), Bureau of Prisons, and Social Security Administration. By examining how Chevron deference has been applied by courts in the recent past, we can gain a workable, albeit imperfect, understanding of which issue areas and agencies are most likely to be impacted should Congress or the Supreme Court pull the plug on Chevron.

Looking Ahead

SOPRA would play a critical role in restraining the excesses of the administrative state. Yet given that the Senate is controlled by Democrats, cloture requires 60 votes, and the White House has threatened to veto the bill, SOPRA – which cleared the House of Representatives in June – is unlikely to become law. Perhaps more modest legislative efforts to rein in the administrative state may be possible. In the meantime, Congress should take care to write statutes with greater specificity so that agencies can focus on administration. As Adam J. White, the Co-Executive Director of the Antonin Scalia Law School’s C. Boyden Gray Center for the Study of the Administrative State, said in response to a question at a House Committee on Oversight and Accountability hearing about red tape, “Congress needs to write more standards itself so that the agencies can focus on enforcement because…enforcement is often sorely lacking. …Congress should write the policies. Agencies should enforce them.” Moreover, members of Congress should treat any legislation that delegates power to agencies with a dose of skepticism and recognize that agency administrators and bureaucrats may attempt to interpret legislative grants of authority expansively in the future. Statutes should be tailored to foreclose this possibility as much as reasonably possible.

Although a legislative override of Chevron seems unlikely in this Congress, the Supreme Court may take matters in its own hands. Next term, the Court will consider Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, in which the U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit deferred to the National Marine Fisheries Service’s interpretation of a provision of the Magnuson-Stevens Fishery Conservation and Management Act of 1976. The question before the Supreme Court will be whether to maintain, sharply curtail, or overrule Chevron v. NRDC. Justices Neil Gorsuch and Clarence Thomas have indicated their desire for the Court to disavow Chevron deference, and the fact that Loper Bright Enterprises was granted cert means that at least four justices are interested in considering the merits of judicial deference to the administrative state. Moreover, the Supreme Court has refrained from using Chevron to favor agencies in recent years. An amicus brief filed by the Cato Institute and Liberty Justice Center notes that since the end of the 2015 term, agencies have lost 70 percent of cases that addressed Chevron, which could portend the doctrine’s impending demise. The Supreme Court can resolve Chevron deference’s “descent into muddy indeterminacy” – to borrow the words of University of South Carolina Associate Professor Nathan D. Richardson – and simultaneously offer clarity to lower courts by directly grappling with the validity of Chevron v. NRDC as a matter of precedent and perhaps overturning that 1984 ruling. It appears that the end of Chevron deference is a veritable – but not inevitable – possibility.

Conclusion

Agencies undoubtedly have a great deal of substantive expertise in their issue areas. Yet their aggrandizement of power has allowed mission creep to go unaddressed, raised costs for individuals and businesses, and imbalanced the constitutional separation of powers. If Chevron deference is eliminated or restricted, agencies will have to abide by Congress’ words and intent in framing legislation and will be required to think more carefully about whether proposed rules fall within their duly granted authority. The Supreme Court has the opportunity in Loper Bright Enterprises to arrest the decades-long and accelerating trend of regulatory expansionism. It would be no exaggeration to say that the end of Chevron would be the biggest change to regulatory policy in years.