Insight

March 29, 2021

The Advanceable Child Tax Credit in the American Rescue Plan Act

Executive Summary

- The American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) significantly increases the value of the Child Tax Credit (CTC) and expands eligibility.

- The ARP also converts half of the CTC to a periodic (likely monthly) payment for eligible families.

- Recent experience with similar “advanceable” programs suggests there may be administrative challenges to establishing this program in a timely and effective manner.

Introduction

The American Rescue Plan Act (ARP), signed into law on March 11, provides $1.9 trillion in new spending, transfer payments, and other relief and assistance to households, businesses, and public institutions (e.g. state and local governments). Among the most significant new policies in the ARP, both in terms of cost and visibility to the American public, is a substantial expansion in the amount of and eligibility for the Child Tax Credit (CTC). This is the second significant expansion of the CTC in 4 years, with the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act having temporarily doubled the credit, among other provisions. The most recent expansion stands out, however, because it also includes a provision designed to turn the credit into a monthly payment. While the expansion and “advanceability” of periodic payments are only temporary in the ARP – these expansions expire at the end of the calendar year – congressional Democrats have signaled their intention to extend or make these changes permanent. Nevertheless, recent experience with advanceable tax credits has demonstrated administrative challenges to successful implementation.

Program Design

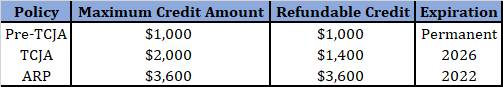

The ARP contains a substantial expansion and modification of the CTC. Under prior law, taxpayers could claim a $2,000 credit per child under the age of 17. The credit phased out for single parents earning over $200,000 and $400,000 for married couples. Taxpayers for whom the credit exceeded their income could claim up to $1,400 per child as a refundable credit.

Table 1: Child Tax Credit Values

The ARP increases, for tax year 2021, the CTC to $3,000 per child, or $3,600 for any child under age 6, and creates a second phaseout, whereby the increased CTC is reduced by $50 for every additional $1,000 over $75,000 for single parents, $112,000 for heads of households, and $150,000 for joint filers. The credit continues to be reduced to the current-law $2,000, at which point the current-law phaseout regime applies.[1] The ARP also increases the age limit for qualifying children to include 17-year-olds. Eligible children must have a Social Security number and be claimed as a dependent by the taxpayer receiving the credit.[2]

The ARP makes the credit fully refundable, such that individuals may receive the full value of the credit in excess of any tax liability. The ARP also eliminates the requirement for taxpayers to have at least $2,500 in earned income to claim the refundable credit. Thus, a single parent with a 4-year-old and a 17-year-old, with $0 earned income would be eligible for a $6,600 benefit under the ARP. The law extends this policy to territories, as well. Combined, the Joint Committee on Taxation estimated that these expansions and modifications to the CTC will cost $109.5 billion over the next decade. If the policy were made permanent, it would likely cost on the order of $1.6 trillion over the next decade.

Periodic Payments

The ARP makes the credit “advanceable” on a periodic basis for eligible families.[3] Under this provision, qualifying families would receive 50 percent of the estimated full value of their child tax credits as a periodic, likely monthly, payment. Like the overall credit expansion, the advanceability regime expires at the end of 2021. Converting a tax benefit, typically realized upon filing a tax return for the prior year, into a contemporaneous monthly benefit is no small administrative undertaking for tax authorities or taxpayers.

Cognizant of the challenge of standing up a new payment regime, the ARP specifies that no payments are allowable prior to July, and necessarily cease in December upon expiration of this temporary provision.[4] So, in the case of the hypothetical family described above, the family would be eligible for $3,300 in periodic payments. Assuming those payments were monthly and began in July, the family would receive six payments of $550 per month.

Claiming the Advanceable Child Tax Credit

The ARP directs the Treasury Department to establish a program for providing the periodic payments to taxpayers who were eligible for the refundable child tax credit based on their 2020 tax filings. If the taxpayer did not file in 2020, this determination can be based on 2019 tax filings. Additionally, the ARP directs Treasury to establish an online portal through which taxpayers can opt out of the program or otherwise update their relevant tax information during the year. Thus, once the program is in operation, taxpayers determined to be eligible for the payments should receive periodic payments without having to take any additional action.

The advanceable credit is based on a prospective credit amount and so is necessarily subject to change if a taxpayer’s circumstances change, such as the number of qualified children in a household or income. The periodic payments must therefore be reconciled against filing data when recipients file their taxes the following year. And here is where some additional complications arise. Over the course of the year in which taxpayers receive the payments, their incomes and family situations may change – new children will be born, incomes will rise and fall, and some parents may gain or lose custody of children. In theory, taxpayers will assiduously update their personal information with the Internal Revenue Service (IRS). In practice, taxpayers will settle up with the IRS come filing time.

The design of the advanceable credit has some built-in cushion to ensure recipients do not receive excessive advanceable payments in the absence of significant changes to personal circumstances by virtue of being only half the estimated credit amount. A change in family status, however, can have a significant effect on a taxpayer’s eligibility to receive the CTC in general and the advanceable payment specifically. Accordingly, the ARP includes a “safe-harbor” provision to preclude the potential for the IRS clawing back overpayments when a claimant files their taxes. For single filers, heads of households, and joint filers with incomes of less than $40,000, $50,000, and $60,000, respectively, ARP provides a $2,000 allowance, per net change in qualifying children, against any excess payments. This safe-harbor is reduced in proportion to a taxpayer’s actual income and 200 percent of their applicable safe-harbor threshold. The ARP does not provide a similar harbor for changes in income or other similar changes in taxpayers’ circumstances. The following examples consider this program in practice.

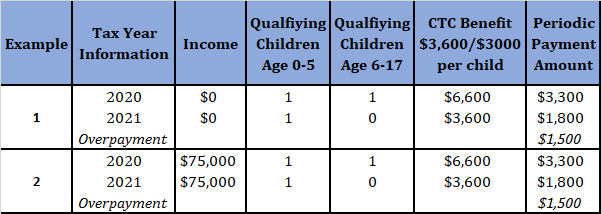

Table 2. Hypothetical Single, Head of Household with Two Qualifying Children as of 2020

The above examples consider two families with qualifying children as of their 2020 tax filings. The first family has an annual income of $0, while the second has an annual income of $75,000. In the first example, the family received $3,300 in periodic payments, based on their 2020 tax filing, which claimed two qualifying children. The example further assumes that the was no longer able to claim their 6 to 17-year-old child as a qualifying child upon filing their 2021 taxes. In this example the family will have received excess periodic payments in the amount of $1,500. In the second example, the hypothetical taxpayer has an income of $75,000 and similarly received $3,300 in payments. In this example, the family was no longer able to claim either child as a dependent upon filing their 2021 taxes. They would have received an overpayment of $3,300.

Table 3. Safe Harbor Calculation

Table 3 walks through the relevant calculations for the applicable safe harbor against clawing back overpayments or reduction in refunds. In the case of example 1, the safe harbor exceeded the overpayment, meaning the taxpayer was held harmless from the effect the change in qualified children had on the taxpayers’ benefit. In the second example however, the taxpayer would have their remaining CTC benefit ($1,800) reduced by $500.

Administrative Challenges

Advanceable individual income tax credits face administrative challenges and have been attempted in the past – specifically an advanceable Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), which was repealed during the Obama Administration. Indeed, refundable credits can face significant error rates. The IRS, for example, has estimated that between 21 percent and 26 percent of EITC claims are paid in error. As noted, above the ARP does not assume these payments will necessarily begin in July; rather they are allowable from July until the end of the year. The statute further does not require that the payments be made monthly.

It remains unclear if the IRS will be able to stand-up this program in a timely manner. The statute states (bold added):

The Secretary of the Treasury (or the Secretary’s designee) shall establish the program described in section 7527A of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986 as soon as practicable after the date of the enactment of this Act, except that the Secretary shall ensure that the timing of the establishment of such program does not interfere with carrying out section 6428B(g) as rapidly as possible.[5]

The law therefore contemplates that the IRS may not be able to establish the portal and make timely payments under this new program, and indeed, it subordinates the urgency of executing this new program to the timely delivery of the latest round of Economic Impact Payments (sec. 6428B(g)). The ARP included $397.2 million and $16.2 million in new funding for the IRS and the Bureau of the Fiscal Service, respectively, to administer the new program, but it remains unclear how quickly and effectively this program can begin operation. In recent testimony, IRS Commissioner Rettig emphasized the significant workload confronting the IRS, not the least of which is the delayed filing season, and raised the potential for delay. Former U.S. Taxpayer Advocate Nina Olson, however, has stated that to get the program up and running, “there needs to be at least 18 months lead time, and even that is a stretch.”

Conclusion

The ARP significantly expands the CTC, in terms of generosity and eligibility. The ARP would establish a new periodic federal payment for qualifying families, likely on a monthly basis, based on the value of a family’s estimated CTC benefit. This is not the first federal experiment with monthly checks based and tax credits. That recent experience with similar “advanceable” programs and agency commentary suggest there may be administrative challenges to establishing this program in a timely and effective manner.

[1] SEC. 9611(a)

[2] Note that families with dynamic living arrangements, additional complexity may arise. See: https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IN/IN11634

[3] SEC. 9611(b)

[4] SEC. 7527A(f)

[5] SEC. 9611 (c)(2)