Insight

January 23, 2020

The Federal Housing Administration: A Primer

Executive Summary

- The Federal Housing Administration (FHA) is a highly significant but under-scrutinized aspect of the housing finance system.

- The FHA acts as a countercyclical source of housing finance when traditional financial markets fail and is a key instrument in providing mortgages to the poorest Americans.

- At the same time, the FHA has loaded the taxpayer with trillions in risky debt and presents a safety and soundness risk to the stability of the U.S. economy.

Context

2019 saw more substantive development in housing finance reform than during the entire eleven years since Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs), entered government conservatorship. While the administration has proposed comprehensive reform to the entire housing finance industry, the vast majority of energy and focus has been dedicated to the GSEs, whose status within the government is particularly uncomfortable.

One aspect of the U.S. housing finance market that avoids most of the attention is the Federal Housing Administration (FHA). This lack of scrutiny does not, however, match the significance of the FHA to the housing market and the resulting danger the FHA poses to U.S. economic stability. This primer sets out the context, history, and the legislative and economic position of the FHA, along with a consideration of both the benefits and criticisms of the agency.

History

Bank failures during the Great Depression forced lenders to call up mortgages owed, which, when combined with widespread unemployment, led to thousands of homeowners being unable to meet their mortgage obligations. By 1933, between 40 and 50 percent of all home mortgages in the United States were in default, with the housing finance system poised for total collapse. Under President Roosevelt, the U.S. government decided to intervene, resulting in, among other New Deal economic policies, the creation of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) by the 1933 Home Owners’ Refinancing Act and the FHA by the 1934 National Housing Act.

The FHA was created with the purpose of stabilizing the housing market by reducing the number of foreclosures on home mortgages, increasing the single-family home market, providing a system of mutual mortgage insurance, and finally promoting the construction of new affordable homes. The Colonial Village in Arlington, Virginia, was the first wide-scale construction project made possible by the FHA and constructed in 1935.

In 1965 the FHA was officially reorganized under the Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD). The FHA must be distinguished from the Federal Housing Finance Agency (FHFA), which also operates under HUD and which supervises the GSEs.

How the FHA Operates

The primary obstacle to home ownership that the FHA sought to overcome was the cost barrier to entry. This barrier had two primary elements for most Americans. First, the inability to present the capital required to meet a down payment, and second, a debt-to-income (DTI) ratio disqualified them from obtaining a mortgage from ordinary lenders. The importance of the DTI ratio in particular has only grown over time, and the Consumer Finance Protection Bureau (CFPB) today does not allow lenders to provide mortgages to individuals with a DTI ratio exceeding 43 percent. But even before the formal CFPB DTI requirement, banks had their own standards. These rules follow simple business sense; conventional wisdom is that individuals with a high DTI are far more likely to default. Banks lending only to those with low DTI and enough capital to make a sizable down payment is simply a function of them limiting their exposure to risk.

Strictly enforcing DTI proscriptions, while excellent economic policy in times of financial stability, necessarily disqualifies a proportion of the population from home ownership. The CFPB therefore created an exclusion to the rule that allowed Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac to provide loans to borrowers with a DTI exceeding 43 percent via what is called the Qualified Mortgage Patch (QM Patch), an exclusion the CFPB has since committed to allowing to expire. (For more information on the QM Patch see here).

Prior to the CFPB and the QM Patch, however, those widespread foreclosures in the 1930s meant that lenders urgently needed a way to bypass their traditional DTI requirements and take on riskier borrowers, and this function was and is still provided by the FHA’s mortgage insurance program.

The FHA’s mortgage insurance is slightly different in form and process than the QM patch. Both the CFPB’s QM Patch and the FHA’s mortgage insurance effectively allow lenders to bypass DTI requirements. But where the two differ is in the assumption of risk. While Fannie and Freddie assume the risk under the QM Patch (with the understanding that the loan is backed by U.S. Treasury), under the FHA’s mortgage insurance, risk remains with individual lenders. If a borrower defaults on a loan the FHA pays the lender the remainder the borrower owes. Because the FHA also represents the federal government, it is tempting to see this distinction as meaningless.

In addition to a mortgage insurance premium, borrowers must also pay interest at 1.75 percent, regardless of the loan amount. The FHA also allows in every case a down payment of 3.5 percent, significantly lower than the requirements of the private market otherwise.

Economics and Market Share

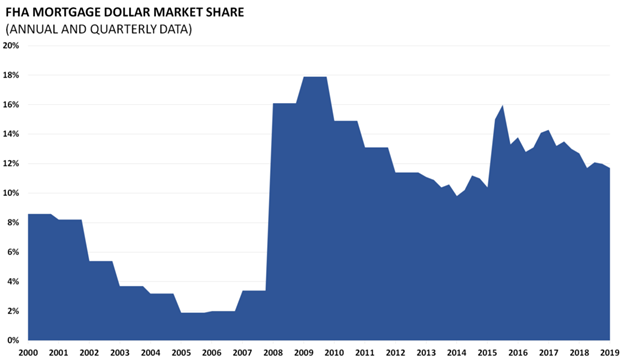

By 2006, the proportion of loans that the FHA financed was less than 2 percent of all U.S. home mortgages, leading to some discussion as to the purpose and future of the FHA. During and following the 2007-2008 financial crisis, however, as sources of conventional mortgage financing evaporated in the credit crunch, many riskier borrowers turned to Fannie, Freddie, and the FHA. By 2009, the FHA insured one-third of all home-purchase loans and almost 18 percent of the market by dollar value (see graph below), and today the figure is not much different. (For up to date housing-market information, see the American Action Forum’s (AAF) quarterly Housing Chartbook.)

Source: HUD

Benefits and Criticisms of the FHA

The benefits and costs of homeownership

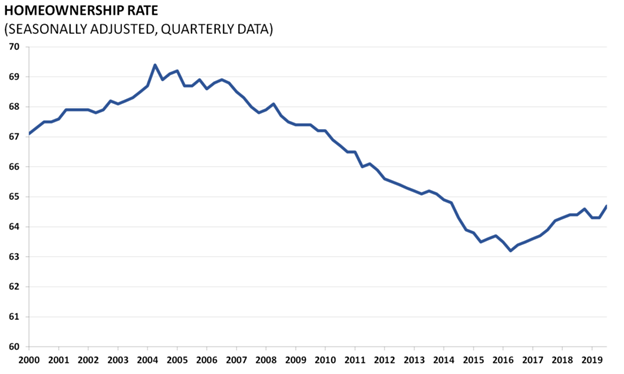

The FHA unquestionably achieved its aim of increasing home ownership. Homeownership increased from 40 percent in the 1930s to 65 percent by 1995, rising to a peak of 69 percent by 2005, and has since returned to 65 percent. although this movement cannot of course be attributed solely, or even predominantly, to the FHA.

Source: U.S. Census

Homeownership, of course, confers many benefits. The Bureau of Economic Analysis determined that the housing market accounted for 12.3 percent of gross domestic product in 2017; the National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) assesses that the annual combined contribution of the housing market averages 15 to 19 percent annually. The benefits of ownership are also conferred on homeowners—primarily the building up of equity, tax advantages, and lifetime cost savings over renting. More philosophically, home ownership is an integral part of the American Dream and represents a driving goal of many Americans.

Homeownership does not simply bring benefits, however, and owning a home does bring costs and can even be devastating. Again, these costs apply to both individuals and to the economy. For the homeowner, a house involves significant financial outlay that might not be regained if the value of your house decreases. Repairs and other maintenance requirements can be expensive. Mortgages are usually more expensive than renting in the short term.

DTI rules are designed to protect vulnerable borrowers from making financially unsound choices, and there will always be proportion of the population that should not own a home to avoid the possibility of default. Programs like the FHA’s mortgage insurance program that bypass these restrictions potentially hurt precisely these vulnerable borrowers.

The FHA is systemically risky

To the economy, the FHA offers a major threat to stability, born of two factors.

First, the degree to which the FHA supports the housing finance system clearly now significantly dwarfs any perceived need to support riskier borrowers. The FHA’s Mutual Mortgage Insurance Fund, the vehicle by which the FHA provides its insurance, reported to Congress that its portfolio was valued at just south of $1.3 trillion for fiscal year 2019. Prudential Financial, the largest insurance company in the United States, has assets under management of $1.5 trillion. The FHA, like Fannie and Freddie, is engaged in riskier activity than the private market but is not regulated by the Federal Reserve for safety and soundness. Guaranteeing the performance of real estate loans is seen by some as the very definition of systemic risk, but the FHA goes further. It is difficult to find a policy justification for the current two-tier system: one system, in the hands of the private market, that does not extend loans to the riskiest borrowers to protect both them and broader economic stability; and a second concurrent system, operated by the government via the FHA and the GSEs, that guarantees $7 trillion in mortgage-related debt to the borrowers least able to repay. The FHA, unusually for a government agency, operates at no cost to taxpayers, but just like Fannie and Freddie in 2013 it too required a $2 billion cash injection in the face of total bankruptcy.

Second, the size of the FHA would pose systemic risk concerns even were it operating as designed and intended – and it is not. It is hard to present the case more elegantly than as HUD itself put it in its Housing Finance Reform Plan:

Since the financial crisis, the risk profile of FHA’s portfolio has increased steadily, endangering FHA’s ability to support access to affordable mortgage credit for first-time homebuyers. Credit scores of borrowers have fallen, while loan-to-value and debt-to-income ratios have increased. The use of down payment assistance programs also has grown significantly. Further, FHA’s activities have strayed away from its core mission—through July of FY2019, 70 percent of FHA refinance endorsements are cash-out refinancing and FHA remains the largest insurer of reverse mortgage products through its Home Equity Conversion Mortgage program. These activities create risks to the solvency of FHA and interfere with its core mission of helping low- and moderate-income borrowers with good credit—yet limited assets—afford a home and build wealth.

Since the 1950s, the FHA has overseen an almost continuous deterioration in credit standards. Between 1990 and 2014 fewer than 10 percent of the loans extended by the FHA would have qualified in the first 20 years of the FHA’s existence. In 2013, the Government Accountability Office identified the FHA as a High-Risk area when, for the first time, the FHA’s capital levels fell below the 2 percent mandated by statute. Although this figure has since recovered to 4.84 percent, this figure is woefully below the figures that would be mandated by the Federal Reserve or the Financial Stability Oversight Council were the FHA regulated as a global systemically important financial institution.

Of particular note are the 2013 comments of Edward Pinto, previously an Executive Vice President of Fannie Mae, who noted that the FHA’s terms were “predatory” and “abusive,” as low-risk borrowers are overcharged in order to subsidize high-risk borrowers.

The FHA serves disadvantaged communities, but also those most likely to default

The FHA has, since the 1960s, provided the support needed to allow for the financing of homes for many minority populations, including the elderly, handicapped, people of color, and younger borrowers constrained by credit. In 2011, Black and Hispanic borrowers accounted for almost a quarter of the FHA’s book of business but less than a tenth of the conventional mortgage market. The success of the FHA in this manner, however, is undercut in two regards.

First, this success comes despite a history of income, gender, and racial discrimination within the institution. The FHA implemented HOLC’s districting classification system that officially and later unofficially prevented low-income families, single women, the elderly, or racial minorities from obtaining loans. The FHA was responsible for the practice of redlining, effectively maintaining racially segregated neighborhoods by preventing minorities from purchasing homes in predominately white areas. Congress passed the Community Reinvestment Act to combat redlining, but the practice has had implications well beyond the impacts felt at the time, and has been a significant force in racial disparity with results still visible today. (More information on the CRA can be found here.)

Second, as noted above, the benefits of homeownership cannot be considered divorced from their cost. In the early 2000s, the Bush Administration made homeownership, and particularly Black homeownership, a policy priority, leading to an expansion in the role of Fannie, Freddie, and the FHA. Bush’s policy objective pushed many Americans, most of them Black, to buy homes they could not afford. The 2007-2008 recession hit these populations hard, especially Black communities for whom their home was a far higher proportion of their overall wealth, leading the American Civil Liberties Union to note that by 2031 white household wealth will be 31 percent below what it would have been apart from a recession, but Black household wealth will be 40 percent lower.

Conclusions

The FHA is predicated on a cost-benefit analysis that has never adequately considered cost. Although there is a real and pressing argument that government intervention was necessary in the 1930s to stave off total housing collapse, its continued role needs to be justified. Perhaps the best argument in favor of the FHA is the suggestion that without it, homeownership during the most recent financial crisis would have dropped far more significantly than 5 percent, although it would be difficult to prove a direct cause and effect. Others make the point more strongly: A 2010 study by Moody’s indicated that, without the FHA, mortgage interest rates would have doubled and home prices would have dropped a further 25 percent as a result of the crisis. Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s, wrote in The Washington Post, “Without such credit, the housing market would have completely shut down, taking the economy with it.” To many, the FHA plays a valuable countercyclical role by providing financing when it would not otherwise be available.

Post-crisis, the FHA has morphed from an emergency source of housing finance to the bedrock of the housing finance system itself. This shift in role poses three major problems. First, government agencies rarely price risk accurately, leading to a housing market increasingly divorced from market realities. Second, the sheer size of the FHA renders it systemically important, but without systemic oversight or regulation. Third, the more the industry relies on the FHA in the ordinary course of events, the less able the FHA will presumably be to provide any countercyclical or emergency capital relief function in the next financial crisis, which is the very point of the FHA.

All this and it is not as though the FHA is providing functions the private market, now considerably more developed than it was in the 1930s, could not. The free market offers private mortgage insurance that covers potential borrowers wishing to buy a home with a down payment as low as 5 percent.

AAF experts have long covered the need for wholesale housing finance reform. Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac, while perhaps the most egregious and obvious examples of a broken system, are not the only offenders. Any vision for the role of government in housing in America must also consider the future of the FHA.