Insight

January 29, 2025

The Inflation Reduction Act and the Future of Price Controls

Executive Summary

While the Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) numerous provisions related to clean energy, corporate taxation, and Medicare pharmaceuticals and biologics are likely to have pronounced future policy effects, the law’s process of setting the maximum fair price (MFP) for a host of drugs covered by Medicare could have the broadest – and most damaging – implications for future economic policy.

- The MFP process has both a traditional statutory price cap as well as a novel price-control feature: the threat of a confiscatory excise tax for those manufacturers that do not offer Medicare’s proposed MFP.

- Though disguised as voluntarily determined pricing, the MFP process is opaque, and the corresponding threat of its punitive excise tax reveals the damaging nature of its price controls, as was demonstrated during the first year of the MFP process.

- Lawmakers, many of whose fondness for price controls is long-standing, may view the “negotiation” of MFPs as a promising approach to impose price controls in many other markets.

Introduction

The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) contains numerous provisions related to clean energy, corporate taxation, and Medicare pharmaceuticals and biologics that are likely to have pronounced future policy impacts. But the law’s provision with the broadest – and most troubling – implications for future economic policy is perhaps its process of setting the maximum fair price (MFP) for drugs covered by Medicare. The MFPs delivered by this process are government-mandated price controls, backed by the threat of extremely punitive excise taxes on drug manufacturers – although the public is likely to perceive them as voluntary pricing arrangements. Lawmakers, many of whose fondness for price controls is long-standing, may view the “negotiation” of MFPs as a promising approach to impose price controls in many other markets.

This insight reviews the key provisions of the IRA and walks through what one can learn from the first round of the MFP process between Medicare and drug manufacturers. The first round of “negotiations” featured the selection of 10 drugs used in Medicare Part D that were subjected to the MFP process. As the drafters of the IRA presumably anticipated, none of the manufacturers chose to run afoul of the 95-percent excise tax and instead accepted the decision of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). The excise tax provides CMS with the force necessary to ensure that manufactures “voluntarily” adopt government-mandated prices for their brand name drugs.

Price controls are damaging and short-sighted, and an anathema in a market-driven economy. Lawmakers, however, are regularly tempted to overlook their manifest flaws in the pursuit of short-run political favor. The MFP process is likely to have pronounced implications for future economic policy by making price controls more palatable to the public and thus may see more widespread use as a policy tool.

Key Provisions of the Inflation Reduction Act

There are two key price-control provisions in the IRA’s MFP process. The first is a traditional, statutory price control labeled the Ceiling on Maximum Fair Price (“the ceiling”). The second is an excise tax advertised as 95 percent – which translates to a 1,900-percent effective tax on the revenues received by the manufacturer – on the sales of manufacturers that do not agree to the government-determined price.

Ceiling on Maximum Fair Price

As summarized by KFF, the “ceiling” is calculated as follows:

The Inflation Reduction Act establishes an upper limit for the maximum fair price for a given drug. The upper limit is the lower of the drug’s enrollment-weighted negotiated price (net of all price concessions, including rebates) for a Part D drug, the average sales price for a Part B drug (which is the average price to all non-federal purchasers in the U.S., inclusive of rebates, other than rebates paid under the Medicaid program), or a percentage of a drug’s average non-federal average manufacturer price (non-FAMP) (which is the average price wholesalers pay manufacturers for drugs distributed to non-federal purchasers). This percentage of non-FAMP varies depending on the number of years that have elapsed since FDA approval or licensure: 75% for small-molecule drugs and vaccines more than 9 years but less than 12 years beyond approval; 65% for drugs between 12 and 16 years beyond approval or licensure; and 40% for drugs more than 16 years beyond approval or licensure. This approach means that the longer a drug has been on the market, the lower the ceiling on the maximum fair price.

Having set the ceiling, the process then turns to a “negotiation” between CMS and the drug manufacturer. Yet it is anything but a negotiation: Refusal to accept the CMS price subjects the manufacturer to the confiscatory excise tax.

The Excise Tax

The excise tax is described by KFF as follows:

An excise tax will be levied on drug companies that do not comply with the negotiation process. The excise tax starts at 65% of a product’s sales in the U.S. and increases by 10% every quarter to a maximum of 95%. As an alternative to paying the tax, manufacturers can choose to withdraw all of their drugs from coverage under Medicare and Medicaid.

It is important to note that the excise tax is 95 percent of the manufacturer’s sales prices, which includes the tax. This “tax on a tax” feature is misleading, however. When the tax is expressed as a percentage of the revenue the manufacturer receives from the sale, the effective rate is 1,900 percent. This means, for example, that the manufacturer would pay $190 in taxes on a sale that yields $10, for a total retail price of $200.

There are two significant implications of this. First, if a company was ever subjected to the tax, it would be passed along to patients in the form of a higher price. (Note that the Internal Revenue Service draws the same conclusion.) Indeed, it would be a much higher price – $200 versus $10 in the example above. Second, in its analysis of the IRA, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected that the excise tax would raise no revenue. Given the magnitudes involved, this can only imply that CBO does not expect it to ever be used. Unlike other taxes, the excise tax has no revenue function and exists only to support the price controls.

It is important to note that the excise tax does not exist in isolation. If the manufacturer does not want to pay the tax, it may withdraw its drugs from coverage under Medicare and Medicaid. In addition, any manufacturer that refuses to offer an MFP to a Medicare or Medicaid beneficiary will pay a civil monetary penalty equal to 10 times the difference between the price charged and the MFP. Finally, all aspects of the MFP regime are cloaked in secrecy. Virtually every aspect – whether a drug is a qualifying single source drug, whether it is subject to negotiation, the determination of the MFP, and other steps in the process – are exempted entirely from administrative or judicial review.

Insights from the 2024 Drug Negotiations

How has the MFP process worked in practice? In August, CMS released the results of the first use of MFP price-setting for 10 drugs:

- Eliquis: A blood thinner used to treat and prevent blood clots and to prevent stroke in people with irregular heartbeats

- Jarelto: A blood thinner used to treat and prevent blood clots while also lowering a patients risk of stroke, deep vein thrombosis, and pulmonary embolism

- Jardiance: Used to treat diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease

- XJanuvia: Used to treat type 2 diabetes

- Farxiga: Used to treat diabetes, heart failure, and chronic kidney disease

- Entresto: Used to treat heart failure

- Enbrel: Used to treat rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and psoriatic arthritis

- Imbruvica: Used to treat blood cancers

- Stelara: Used to treat psoriasis, arthritis, Crohn’s disease, and ulcerative colitis

- Fiasp/NovoLog: Used to treat diabetes

Combined, Medicare patients spent $56.2 billion on these drugs in 2023. Notice that using the 1,900-percent effective tax rate, the potential excise tax totals nearly $1.1 trillion. And yet, when all was said and done, the excise tax produced no revenue. What happened instead?

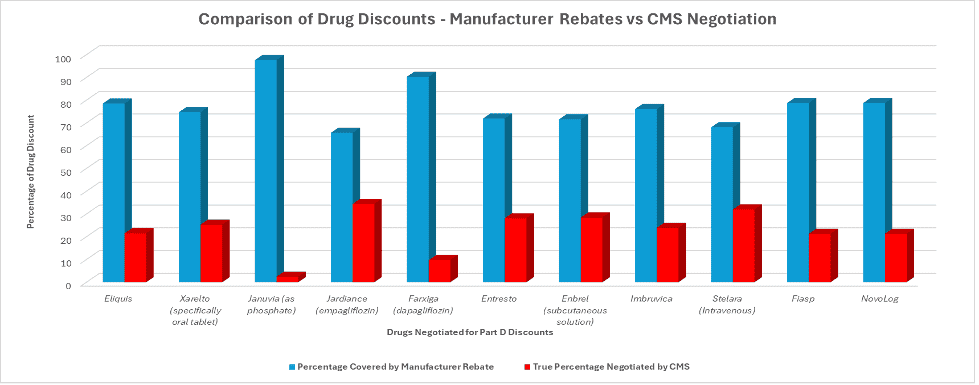

The chart (below) summarizes the percentage reduction in price as a result of market forces (in the form of rebates paid by manufacturers) and the further reduction from the MFP process. It shows that a clear majority of patients’ drug savings was acquired through negotiations between manufacturers’ rebates – offered to secure better placement on insurers’ formularies – compared to the lesser savings extracted from the IRA’s drug pricing provisions.

The chart conveys two important results. First, market forces work, even in the pharmaceutical industry. The percentage reduction from list prices shown in the blue bar are substantial, differ by drug, and are a tribute to the competition for placement on formularies.

Second, the threat of the enormous excise tax “worked.” No manufacturer was subjected to the excise tax and CMS dictated reductions below market equilibrium (as shown by the red bars.)

Conclusions

The IRA’s process of setting the MFP is perhaps its most important feature. That process has both a traditional statutory price cap as well as a novel excise tax that permits price controls to be presented as voluntary pricing decisions. Lawmakers, many of whose fondness for price controls is long-standing, may view the “negotiation” of MFPs as a promising approach to impose price controls in many other markets.

The IRA is damaging enough on its own, but these potential implications are the greatest danger from the law.