Insight

April 8, 2025

The New U.S. Carbon Tariff Proposal: A Brief Overview

Executive Summary

- Today, Senator Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) reintroduced the 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA), which would levy tiered and escalating tariffs on selected imported goods base on their carbon emissions, with the intention to boost U.S. manufacturers’ competitiveness in low-carbon goods and raise tax revenue.

- The 2025 FPFA would likely raise significantly less revenue compared to the 2024 discussion draft, as the original provision of a 15-percent base rate on all covered imported goods (regardless of their carbon intensity) has been eliminated, and the tax base has been narrowed to apply only to imported goods that are more carbon-intensive than U.S. peer goods.

- Carbon tariffs will not make U.S. manufacturers more competitive, as they will raise the price of imports, reduce the real after-tax incomes of workers, increase the cost of investment for U.S. firms, and hurt U.S. exports’ competitiveness due to the appreciated U.S. dollar.

Introduction

Today, Senators Bill Cassidy (R-LA) and Lindsey Graham (R-SC) reintroduced the Foreign Pollution Fee Act (FPFA), which would levy tiered and escalating tariffs on selected carbon-intensive imported goods. This legislation was originally introduced in November 2023 and updated in a discussion draft released in December 2024.

The discussion draft of the FPFA would levy a flat 15-percent carbon tariff on goods imported into the United States across six sectors: aluminum, cement, iron and steel, fertilizer, glass, and hydrogen, with a surtax of 40 percent based on the carbon intensity of these goods. The 2025 FPFA has made some changes to the legislation by eliminating the 15-percent base rate and creating a multi-tiered tariff framework. These changes will likely significantly reduce the revenue raised compared to the previous policy design.

Carbon tariffs will not make U.S. manufacturers more competitive, as they will raise the price of imports, reduce the real after-tax incomes of workers, increase the cost of investment for U.S. firms, and hurt U.S. exports’ competitiveness due to the appreciated U.S. dollar.

Notably, this piece is intended as a brief overview of the new proposal. A more in-depth analysis will be released later.

Overview of the 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act

The 2025 FPFA works by applying an escalating tariff on certain imported carbon-intensive goods.

Legislation Objective

In a recent op-ed, Senator Cassidy argued that the FPFA is intended to counter “China’s unfair trade practices, namely through exploiting its lax environmental standards to undercut the United States,” and that the proposal “will bolster the global competitiveness of U.S. manufacturers, forge relationships with our internal trading allies, and bring in new revenue to the U.S. treasury.” He also stated that the revenue raised through the FPFA would help pay for President Trump’s tax cutting agenda, referring to the pending Republican reconciliation bill aimed at extending the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Tax Base

The bill would levy an ad valorem tax on imported goods, meaning the tariff amount is set in proportion to a good’s customs value. It covers aluminum, cement, iron and steel, fertilizer, glass, hydrogen, and certain inputs for solar and battery manufacturing.

Tax Rate

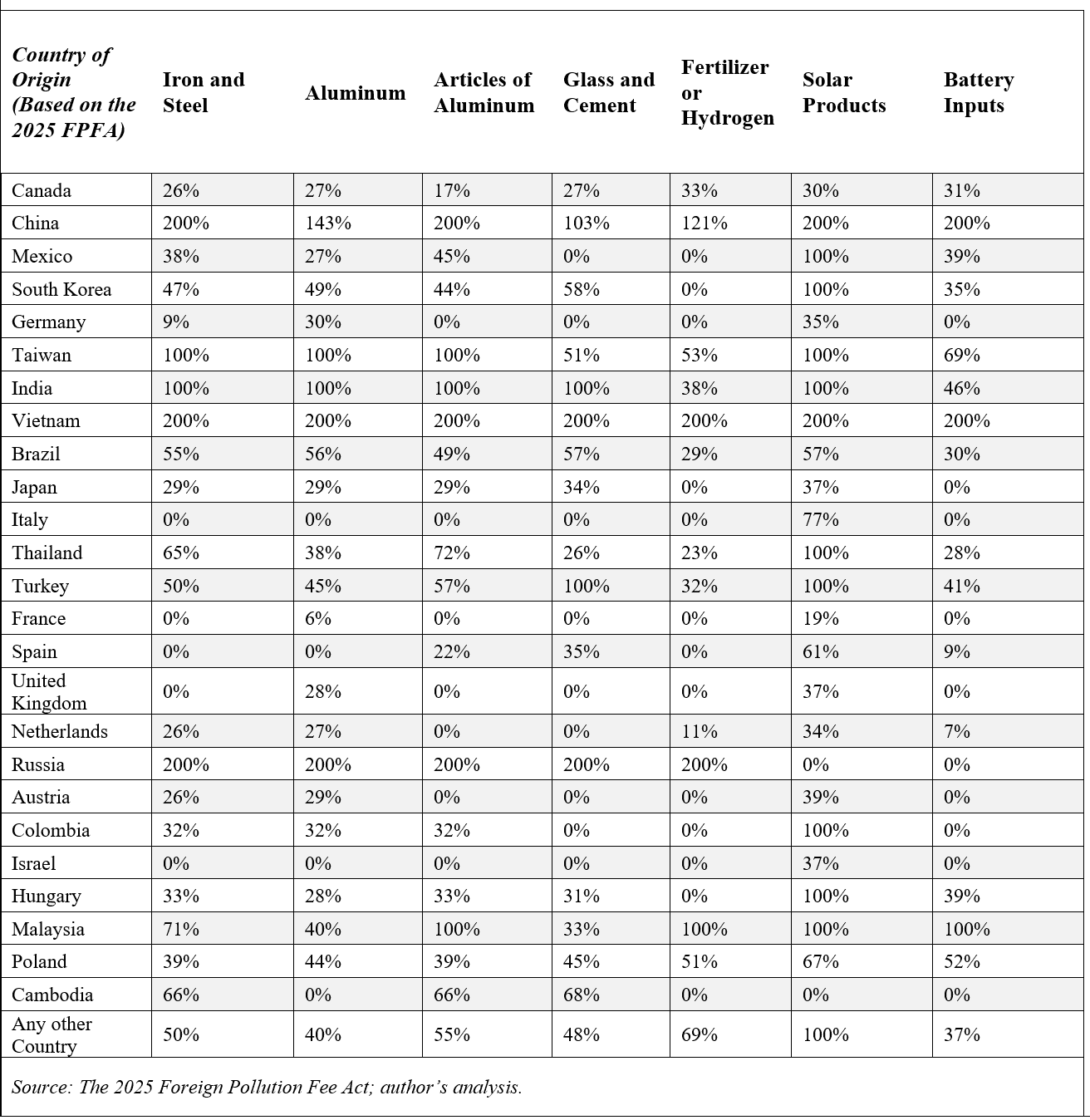

The tariff would have a variable rate under a multi-tiered tariff framework, which would subject more carbon-intensive imports to higher rates. The tax rate is a variable percentage specific to a covered good from a country of origin. As shown in the table below, the tiered tariff framework would assign countries and sectors to different tiers based on their carbon intensity relative to their U.S. peer sector. The tax rates would escalate across tiers, and they also vary within the same tier. Exporters of covered goods would be subject to the variable charges in the table during the first three years of the legislation’s implementation. After that, the variable charges would escalate based on different criteria listed in the legislation.

Developing countries such as India and Vietnam would be subject to much higher tariff rates than developed countries such as France and Germany. For example, all sectors of covered Vietnamese goods would be subject to 200-percent tariff rates. In contrast, most of France’s covered sectors of goods would not be subject to tariffs.

China and Russia would face high tariff rates, with most of their covered sectors’ rates set at over 100 percent. Canada and Mexico, the United States’ most important trading partners, would also be subject to various tariff rates as low as 0 percent, and as high as 100 percent for their covered goods.

Table 1. 2025 Foreign Pollution Fee Act Variable Charge by Sector and Country of Origin

Special Features

The 2025 FPFA retains many provisions from its earlier version that allow exceptions or a reduction of tariffs, including through an “International Partnership Agreement” that could fully exempt a country’s imported goods if the country implements equivalent environmental and trade policies. The legislation also includes stringent punitive tariff measures to discourage circumvention and transshipment to other countries with lower tariffs rates, which are falsely declared as the origin of imports to evade taxes.

Revenue

The 2025 FPFA would likely raise significantly less revenue compared to the 2024 discussion draft, which was estimated to raise about $212.8 billion from 2026–2035.

Two major changes in the 2025 legislation compared to the 2024 version will reduce the revenue effect. First, the 15-percent base rate on all covered imported goods regardless of their carbon intensity has been eliminated. Second, the tax base has been narrowed considerably to apply only to imported goods from countries that are more carbon-intensive than those from the United States.

Analysis

Carbon tariff advocates believe that imposing tariffs on carbon-intensive imported goods would make cleaner American goods more competitive in the global market, boost U.S. manufacturing jobs, and increase economic growth. There are good reasons to price carbon as part of a broad-based carbon tax, but the economic effects of tariffs are clear: They will reduce economic growth and lower living standards.

Tariffs raise the price of imports. These higher prices reduce the real after-tax incomes of workers and increase the cost of investment for U.S. firms. As a result, labor supply and investment in the United States would fall. Tariffs often fall on inputs used by U.S. manufacturers, raising their production costs. Furthermore, tariffs would result in an appreciation of the U.S. dollar and foreign retaliation in the form of tariffs on U.S. exports. All these factors would burden U.S. exporters, making them less competitive in global markets.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen what the future developments of the FPFA will be amid President Trump’s ongoing sweeping global tariffs and the pending reconciliation bill. Nonetheless, carbon tariffs will raise the price of imports, hurt U.S. manufacturers, and impede U.S. economic growth.