Insight

September 16, 2018

The T-Mobile-Sprint Merger and False Market Distinctions

On April 29th of this year, T-Mobile and Sprint agreed to merge, triggering a wave of regulatory review from both federal agencies such as the Federal Communication Commission and the Department of Justice and state attorneys general. Among the issues the New York Attorney General is exploring regarding this deal is how the merger might affect the market for prepaid cellular services. Together, T-Mobile and Sprint have about 30 million prepaid customers.

To understand the impact of a potential merger on prepaid customers, it is important first to determine the degree to which the existing prepaid and postpaid customer bases represent two distinct wireless markets. A review of the evidence finds

- Prepaid and postpaid deals are two segments of the same wireless market;

- The segmentation largely comes from differences in credit scores and credit worthiness, and as credit scores rise, more people move into the postpaid segment, which has more benefits; and

- The deal could spur more competition within the prepaid segment of the wireless market.

Certainly, these aspects of the merger should not be a reason for the deal to be stopped.

The Relationship Between Prepaid and Postpaid Segments

To investigate the competitive effects of the T-Mobile-Sprint deal on prepaid and postpaid services, it is important first to understand how they operate. A prepaid mobile service requires that the user purchase credits ahead of time, such that at the beginning of each month, a user has an allotment of minutes, texts, and data she can use. When this bundle runs out, the service is usually throttled until the next month or when the user purchases more. On the other hand, a postpaid mobile service bills a user at the end of each month after he uses the service. Postpaid service requires that the user enter into a contract that specifies a limit to how many minutes, text messages, or days can be used in that month. If a user goes over that limit, he incurs extra charges. Contracts also usually include some sort of payment plan for a physical phone.

What really differentiates prepaid and postpaid services is the extent to which a company extends a loan, both for the phone (in most cases) and for the charges that may be incurred over a month. In other words, they are differentiated by the underlying contract, not by a difference in market.

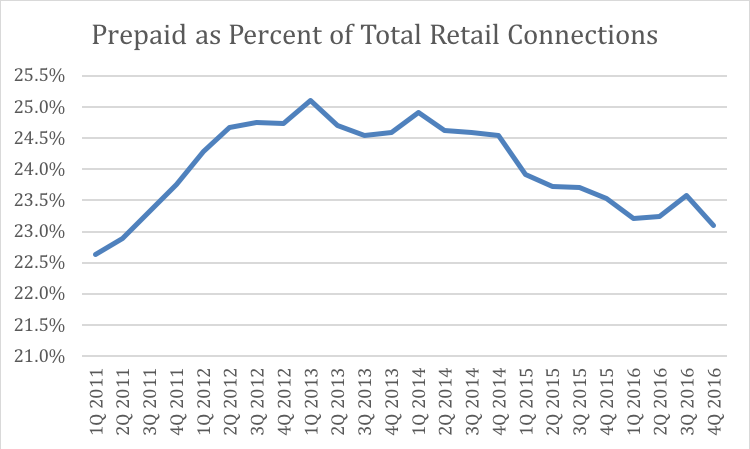

Bucking analysts predictions, both the prepaid and postpaid subscriber base expanded in the second quarter of 2018, according to the most recent data filed by wireless carriers. Yet, the overall trend in the number of prepaid users is downward, as the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) detailed in their most recent wireless competition report. Below, these data are mapped, showing the number of prepaid customers as a percent of all retail connections.

T-Mobile CEO John Legere explained what was driving the change in a recent earnings call:

So what’s happening is more people are qualifying for postpaid than they were a year or two ago and when you can qualify for postpaid, a lot of people take it because they want these device financing deals that they’re now qualifying for. So I think that’s been a healthy trend for the industry and it’s at least in part driven by the economy.

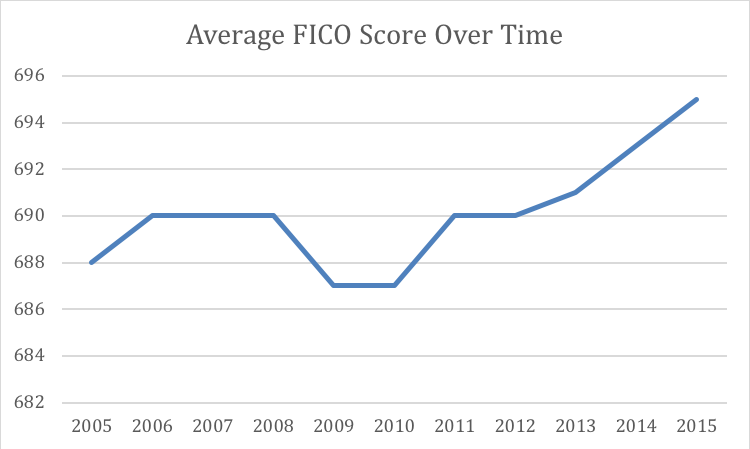

Putting it all together, the trend makes sense. As the economy has improved and consumers have more income, average credit scores have been marching upwards. Thus, those who would have previously been limited to prepaid accounts have the opportunity to switch to postpaid services, which they take. The chart below details the increase of average FICO scores in the last couple of years.

The relationship between credit and contracts helps to explain why Sprint began using Progressive Finance in 2016 to conduct credit checks. Because the company has developed methods to better understand credit risk, as one industry insider, “Sprint may be able to continue to court consumers with subpar credit while minimizing the risk of not getting paid for devices and services.”

Thus, the prepaid and postpaid distinction isn’t due to a difference in markets, but a difference in the contract and consumer choice. In exploring the difference between a prepaid and postpaid contract, the FCC agreed that the difference comes “largely because prepaid subscribers may lack the credit background or income necessary to qualify for postpaid service.” Moreover, the agency previously agreed with this assessment in its analysis of the failed AT&T merger with T-Mobile, noting,

We recognize the product market we define encompasses differentiated services (e.g., voice-centric or data centric), devices (e.g., feature phone, smartphone, tablet, etc.), and contract features (e.g. prepaid vs. postpaid), and that wireless providers often recognize such distinctions in their internal analyses of the marketplace. While such distinctions may suggest the possibility of smaller markets nested within the product market we define, we find it unnecessary to examine that possibility in order to analyze the potential competitive effects of this transaction. We consider these aspects of product differentiation, as appropriate, when we analyze the competitive effects of the transaction within the markets we define.

Because prepaid customers are moving toward postpaid plans, the prepaid segment is best understood as a subset of the larger cellular market. Any analysis of this merger that focuses simply on its effect on the prepaid subset will necessarily provide an incomplete understanding.

To take on the New York Attorney General’s question directly, however, if this current merger were to go through, the prepaid sub-market could change for the better. Overall, the broad wireless market has been competitive, but the rate of new consumers has been slowing. Combined, those features have driven carriers increasingly to focus on the prepaid segment to spark revenue growth. For example, Verizon hadn’t put much effort into courting the prepaid market, since the carrier assumed that offering more prepaid services would lead to “potential cannibalization from its high-value postpaid subscriber base.” But the pressures of the market and the possibility of a rival in a combined T-Mobile and Sprint drove the company to double the data allowance on their prepaid offerings in late June.

Indeed, in 2013 T-Mobile helped to blur the lines between prepaid and postpaid choices when began to offer postpaid service on a month-to-month basis without contracts. This deal also gave consumers the ability to pay for a portion of their cellular device up-front and then pay off the rest over time. When the payments were completed, the user would own the phone, in contrast to the subsidy model where consumers would continue paying an additional fee until they upgraded to a new device. Today, consumers differentiate less between prepaid and postpaid as the characteristics that historically separated these services have blurred into an array of financing and purchase options.

The question over the prepaid segment being a separate market is just one part of several that regulators are diving into to approve the companies’ merger. But, as it stands now, this aspect doesn’t call for the deal to be sunk. Cellular customers on the whole are moving toward postpaid services, which offer better benefits, and the threat of more competition is encouraging some companies to offer more to prepaid customers.