Insight

May 20, 2020

The Threat of Bankruptcies in the Petroleum Producing Industry

Executive Summary

- Despite some rebound in oil prices since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, significant numbers of bankruptcies are expected among oil and gas producers in the coming year, even with expanded access to the Paycheck Protection Program and forthcoming Federal Reserve loans.

- This spate of bankruptcies threatens the stability of the resource-rich regions that rely on oil and natural gas production to anchor their economies, but also the economy at large.

- As industry-specific assistance has proven largely unsuccessful, forthcoming rounds of COVID-19 relief legislation should ensure that those regions with growing unemployment in production have adequate programming to support workers.

Unsuccessful Aid Proposals

As the oil market declined throughout March and April, the Trump Administration pursued various means to aid the oil production industry by leveraging the Strategic Petroleum Reserve. These attempts to remove oil supplies from the market through several rounds of purchases and leases have largely proven unsuccessful. When West Texas Intermediate oil futures hit historically low negative prices on April 20, 2020, President Trump once again called for a plan to aid domestic oil and gas producers. Unlike previous plans that aimed to reduce the supply on the market in order to increase prices, the administration’s most recent plan aimed to provide funds directly to producers. But as oil futures prices have risen in recent weeks and the Federal Reserve has extended its loan programming, the administration has stopped actively pursuing assistance.[1]

Throughout there has been a lack of consensus on the extent to which oil demand will recover and when, both executive and legislative commitment to assisting the industry, and the Federal Reserve’s intentions in expanding its loan programs. With oil and natural gas producers subject to unprecedented market conditions, one thing is sure: An increased number of companies will go bankrupt as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Some industry participants and trade organizations suggested that the industry did not need federal assistance while others suggested targeted aid would be worthwhile as producers may not qualify for small business loans or be able to secure financing from traditional lenders.[2] Concerns have been focused on small- and medium-sized, or independent, producers that are more likely to be short on cash and heavily in debt, making them undesirable candidates for private financing. This paper provides a review of producer bankruptcies in the United States and an update on programming available from the Federal Reserve to aid producers.

Who are Producers?

Producers vary in terms of their number of employees, number of wells, geographic location, and quantity and quality of oil and natural gas extracted. These factors shape each company’s operations and financial wellbeing, with some operating individually profitable wells while others are only capable of making ends meet by aggregating the production of multiple wells.

A large majority of the oil and natural gas produced in the United States—83 percent and 90 percent, respectively—is brought to market by independent producers. The term independent producer is defined by the Internal Revenue Code as a producer who neither transacts more than $5 million in retail sales nor refines more than 75,000 barrels per day of oil within a year. According to the Independent Producers Association of America, there are about 9,000 such producers in the United States operating in 33 states and offshore. While each employs only 12 people on average, combined they account for 3 percent of total gross domestic product.[3]

Independent producers are in a difficult position: The oversupplied market must be balanced by reducing production, but revenue from production may provide access to more financing options. Some producers are encouraged to continue producing to meet debt-to-earnings ratios typically enforced in the terms of loans. Production of proven reserves can also serve as a borrowing base, granting producers access to additional funds when they need them most. An excessive reliance on debt to continue operating has led some producers to be rated as speculative grade rather than investment grade by credit-rating agencies. Moody’s, a credit rating agency, estimated that speculative grade industry held $86 billion, or 63 percent, of debt held by industry in March that would mature during the next four year, a “staggering amount.”[4]

While independent producers include companies characterized as small- or medium-sized, large producers include major and supermajor producers. Some of these companies are household names and can withstand the financial implications of an unforeseen downturn in demand. They are also considered healthy enough to continue relying on traditional capital markets for additional financing.[5] As a result, they are less likely to become insolvent and not in need of government support.

In total, the oil and gas production industry employs over 460,000 workers according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, a number that has declined since February.[6] In March, 51,000 production and refining jobs were lost, a 9 percent decrease that highlights the downstream effect of production cuts.[7] Job losses are projected to reach 30 percent.[8] These losses will be felt most in local and regional economies where the natural resources are located. The largest oil producer in the United States, Texas, is projected to lose up to one third of its 300,000 production jobs in 2020. When considering the various downstream businesses dependent on oil production as well as the boom towns that grow around production, the fallout becomes much larger. Texas is estimated to lose 1 million jobs in 2020 when considering these affiliated services and products.[9]

Bankruptcy Among Producers

When companies are no longer able to meet their obligations, they can file for bankruptcy, which can result in the restructuring of a company’s debt and assets or dissolve the company. Dramatic cuts in production in recent weeks have reduced producers’ earnings and led to fears that they will be unable to meet their obligations. Some companies have begun to skip payments to creditors in an effort to maintain as much cash on hand as possible.[10]

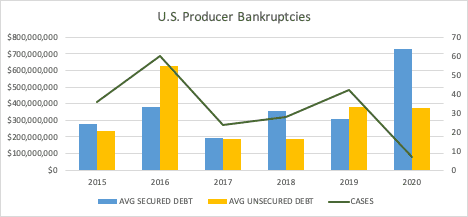

Source: HAYNES AND BOONE, LLP OIL PATCH BANKRUPTCY MONITOR

Source: HAYNES AND BOONE, LLP OIL PATCH BANKRUPTCY MONITOR

The true impact of the reduced demand for petroleum products caused by COVID-19 and the resulting economic downturn has not yet been felt. During the past year, the price-sensitive industry has depended on about $50 per barrel to break even with regional variation.[11] Estimates of the number of bankruptcies have varied from “hundreds” to more specific estimates like 140 producers with oil at $20 per barrel and 73 with oil at $30 per barrel.[12] Prices have recovered slightly, now above $20 per barrel, but still over 50 percent less than the beginning of the year.

The values reflected for 2020 in the chart above only include cases filed through April 1 while prior years’ values reflect caseloads for the whole calendar year. When compared to prior years’ first quarters, the number of cases in 2020 does not stand out. The total value of debt for these seven cases, however, is greater than that for whole previous years. This increase reflects the difficulties producers faced in the past couple years to break even, particularly producers operating in shale plays who relied on growing debt to continue operating.[13]

Many of these companies were anticipated to become bankrupt in the next few years as their debt matured, regardless of the pandemic. Their assets, i.e. the land rights and natural resources within the reservoirs, remain valuable, however. Those assets may be acquired by surviving companies. As a result, the pandemic is effectively catalyzing the consolidation of the industry.

Since April 1, several producers have filed for or announced that they intend to file for bankruptcy. The extent to which demand rises in response to loosening shelter-in-place orders and drives up prices will decisive for the survival of some producers. The Energy Information Administration has forecasted decreased demand for oil and liquid fuels to continue throughout 2020 and 2021 when compared to 2019 levels due to the pandemic’s lasting impact on travel.[14] The Secretary of Energy, on the other hand, has suggested that the market will return to pre-pandemic levels within six months with some inevitable bankruptcies.[15]

With thousands of independent producers operating in the United States, the loss of some companies, especially those who were already struggling financially prior to the pandemic, is a testament to the efficiency of the market. Their concentration in particular regions, however, can create dramatic results. Some state governments have attempted to aid producers to avoid this type of economic fallout by deferring royalty payments or creating more favorable tax laws that in effect leave producers with more cash. Such changes, however, leave states in a precarious position because they rely on this revenue to fund state level programming.

Loan Programming

In response to the COVID-19 pandemics shuttering much of the economy, the Federal Reserve announced the Main Street Lending Program while the Small Business Administration received additional funds via the Paycheck Protection Program to supplement sources of emergency relief. These funds may be available to companies that met specific criteria such as number of employees and annual revenue but did not target specific industries. Although the Paycheck Protection Program is now disbursing a second round of funding, no start date for the Main Street Lending Program has been announced.

Upon announcing the initial terms of its programs, the Fed sought feedback to ensure that its criteria met the varied needs of businesses, leaving the possibility of amending its programming open. In turn, members of Congress and trade associations solicited the Federal Reserve directly on behalf of producers.[16] The feedback included requests to broaden Main Street criteria by allowing producers to use more favorable bond scores issued earlier in March before the effects of the oversupply were felt, loosen credit score requirements, and allow producers to use loans to pay off existing debt.[17]

On April 30 the Fed announced that it expanded the scope of eligibility for the Main Street Lending Program to include companies with less than 15,000 employees rather than 10,000 and $5 billion in revenue rather than $2.5 billion.[18] The program supports three types of loans that cap the funds available to borrowers based on their ratio of debt to 2019 earnings, suggesting that while larger companies may now apply for loans, they must be financially healthy. As a result, the Main Street Lending Program does not address the concerns of producers that had accumulated unhealthy amounts of debt prior to the onset of the pandemic. But what does that mean for those who would be healthy enough to apply?

Given the size of most independent producers, they are the small- and medium-sized companies policymakers were aiming to assist, so it appears that the number of employees or revenue are not barriers to entry for participation in the Main Street Lending Program. The program is not operating, however. Additional terms such as the necessity to meet financial obligations for at least the next 90 days and avoid filing for bankruptcy, or pay off the loan in four years, however, may be difficult to determine for an industry very dependent on market prices, which are historically low. Similarly, truly small producers with fewer than 1,000 employees could apply for the Paycheck Protection Program, but funds are nearly exhausted and there is a lack of clarity on when to expect the next round or if criteria will change.

While the administration is touting the revised programming as a success because it provides access to medium-sized producers, the Federal Reserve cannot provide industry-specific assistance nor can it help businesses that are not solvent.[19] Rather than focusing assistance on particular segments of the industry, upcoming legislation should ensure that those states and regions impacted most by job losses are appropriately supported. While assisting the industry is unpopular among Democrats due to its contributions to climate change, its employees should not be overlooked.

Conclusion

Many oil and natural gas producers are operating on thin margins and may even have accumulated unhealthy amounts of debt. While large producers may access traditional avenues of financing, small- and medium-sized producers, especially those that are not creditworthy and cannot pursue traditional financing, are left with few options in terms of aid. Limited access to funds in combination with low projected demand suggest that 2020 will see a surge in bankruptcies, but just how many is yet to be seen. These bankruptcies will exacerbate the levels of unemployment already growing in certain regions of the United States.

[1] https://www.eenews.net/energywire/2020/05/11/stories/1063103809

[2] https://www.wsj.com/articles/texas-regulators-decline-to-force-oil-cuts-but-companies-are-cutting-anyway-11587486457?mod=searchresults&page=1&pos=4

[3] ipaa.org/independent-producers/

[4] https://www.moodys.com/research/Moodys-North-American-exploration-and-production-firms-face-high-debt–PBC_1215097

[5] https://www.eenews.net/energywire/2020/05/06/stories/1063060139

[6] https://www.bls.gov/iag/tgs/iag21.htm

[7] https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2020-05-12/big-oil-has-big-plans-for-net-zero-are-they-credible

[8] https://www.ibtimes.com/us-oil-gas-industry-enduring-devastating-job-losses-supply-glut-low-crude-prices-2963933

[9] https://www.cbsnews.com/news/crude-oil-prices-slump-could-cost-texas-1-million-jobs-this-year-alone/

[10] https://www.wsj.com/articles/embattled-energy-companies-snub-creditors-to-conserve-cash-11585945549

[11] https://www.dallasfed.org/research/economics/2019/0521

[12] https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/20/business/oil-price-crash-bankruptcy/index.html

[13] https://www.ft.com/content/c1be5ca0-695a-11ea-800d-da70cff6e4d3

[14] https://www.eia.gov/outlooks/steo/pdf/steo_full.pdf

[15] https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20200514005142/en/U.S.-Secretary-Energy-Dan-Brouillette-America%E2%80%99s-Role

[16] https://www.cruz.senate.gov/?p=press_release&id=5071

[17] https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/powerpost/paloma/the-energy-202/2020/04/29/the-energy-202-oil-companies-have-a-new-lobbying-target-during-pandemic-the-federal-reserve/5ea8572e602ff145784205d0/; https://www.ipaa.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/04/Main-Street-Lending-Letter-04-15-2020.pdf

[18]https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200430b.htm; https://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/monetary20200430a.htm

[19] https://www.eenews.net/energywire/2020/05/15/stories/1063138915