Insight

October 26, 2022

Why the Consumer Welfare Standard Is the Backbone of Antitrust Policy

Executive Summary

- The consumer welfare standard has been the backbone of antitrust policy for over 40 years and provides a consistent basis for the enforcement of antitrust law.

- The consumer welfare standard is measurable using economic analysis and empirical evidence, facilitating a reliable and objective application of antitrust law.

- Commandeering antitrust policy as a tool to solve other societal ills including depressed employee wages and harm to competitors risks creating uncertainty, stifling innovation, and slowing economic growth.

Introduction

Antitrust policy sets the rules that govern competition in the economy. Despite a long history of ebbs and flows in antitrust policy application, the consumer welfare standard has been the backbone directing antitrust enforcement and litigation for more than 40 years.

The consumer welfare standard guides antitrust enforcers and the courts when evaluating the effects that a particular business practice or merger has on the consumer. To do this, economic tools and data are used to measure if the business practice or merger in question will raise prices, reduce output, or stifle innovation. Any result negatively impacting the consumer, as defined by the consumer welfare standard, may be deemed violative of antitrust laws.

More recently, this standard has come under attack. Antitrust enforcement is morphing into a tool to pursue other policy initiatives including mitigating depressed employee wages, minimizing inequality, limiting harms to competitors, and preventing the rise of big firms that have amassed political power. This philosophy has gained momentum. Subscribers to this theory include Federal Trade Commission (FTC) Chair Lina Khan and members of Congress who have recently proposed several pieces of antitrust legislation. Abandoning the four-decade-old consumer welfare standard for antitrust enforcement and reverting to an ad hoc subjective regime risk creating uncertainty, stifling innovation, and slowing economic growth.

Emergence of the Consumer Welfare Standard

The consumer welfare standard was not always the North Star guiding antitrust jurisprudence. Prior to its development and adoption by the courts, a more subjective and ad hoc approach was applied.

Congress passed the Sherman Act in 1890, the first antitrust law in the United States. In 1914, Congress passed the Federal Trade Commission Act that created the Federal Trade Commission and the Clayton Act. While the acts have been amended over time, these pieces of legislation are the “three core federal antitrust laws …in effect today.” [1]

Former FTC commissioner and law professor Joshua D. Wright explained that the Sherman Act was passed “following a rash of ‘great trusts’ arising at the end of the nineteenth century.” He explained that “the Antitrust Agencies and courts…initially interpreted the antitrust laws as existing primarily to prevent ‘bigness’, that is, to preserve the small, localized businesses….”[2]

Wright noted that “seven years after the Sherman Act was passed, the Supreme Court in United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Association, for instance, held the goal of antitrust law is to protect ‘small dealers and worthy men.’” In the decision, the “Court, in fact, went so far as to conclude that these small dealers and worthy men should be protected even if doing so came at the expense of ‘[m]ere reduction in the price of the commodity.’” [3] In other words, rather than shielding consumers from harm, the Court protected competitors.

A similar ruling was issued in United States v. Aluminum Co. of America in which “Judge Learned Hand wrote that ‘great industrial consolidations are inherently undesirable, regardless of the economic results’, and that bigness was to be prevented owning to ‘the helplessness of the individual before them,’” Wright explained. [4] Wright claimed that “These pronouncements were consistent with the antitrust approach the courts had adopted for over the last fifty years. They were, however, also at odds with an area of law designed to protect economic results…. [T]he Court decreased the purchasing power of individual consumers…and issued opinions that explicitly chose to foster corporate welfare over consumer welfare.” [5]

Other cases including Brown Shoe Co. v. United States, United States v. Philadelphia National Bank, and United States v. Von’s Grocery Co. solidified the notion that antitrust law protected competitors rather than competition and consumers. [6]

Landmark rulings protecting competitors at the expense of consumers were pervasive throughout the 1960s. This prompted economists and legal scholars to “discuss the proper goals of antitrust law and how to construct a workable regime. They sought – and ultimately realized – an economic grounding that would provide a principled basis for antitrust decision marking” [7] In the 1970s, legal scholar and future judge Robert Bork led the charge.

In 1978, Bork wrote “The Antitrust Paradox: A Policy at War with Itself.” The book was the culmination of previous writings in which Bork developed the idea that consumer welfare should be the crux of antitrust law and litigation. He explained that “competition leads to firms to engage in conduct that benefits consumers – it drives price cuts, output expansions, research and development, and other innovative efforts.” [8]

A year after “The Antitrust Paradox” was published, the Supreme Court cited Bork in its Reiter v. Sonotone decision concluding that “Congress designed the Sherman Act as a ‘consumer welfare prescription.’” [9]More than 30 years after “The Antitrust Paradox” was published, the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines (HMG), jointly published by the Department of Justice and the FTC, included sections alluding to the “consumer welfare standard.”

Section 1 of the HGM reads, “The unifying theme of these Guidelines is that mergers should not be permitted to create, enhance or entrench market power…. A merger enhances market power if it is likely to encourage one or more firms to raise prices, reduce output, diminish innovation, or otherwise harm customers….” Furthermore, Section 10 states “the Agencies will not simply compare the magnitude of cognizable efficiencies with the magnitude of the likely harm to competition absent the efficiencies. The greater the potential for adverse competitive effect of a merger, the greater must be the cognizable efficiencies, and the more they must be passed through to customers….”[10]

The HGM leaves little doubt that the antitrust enforcement agencies are using the consumer welfare standard as the driving principle of merger evaluation and other antitrust litigation.

The consumer welfare standard’s foundation in economic principles, empirical analysis, and impartiality in antitrust law application are among the reasons it was quickly adopted by the courts. Court decisions have routinely cited Bork’s idea that antitrust laws are designed to protect competition and promote consumer welfare.

Consumer Welfare and Total Economic Efficiency

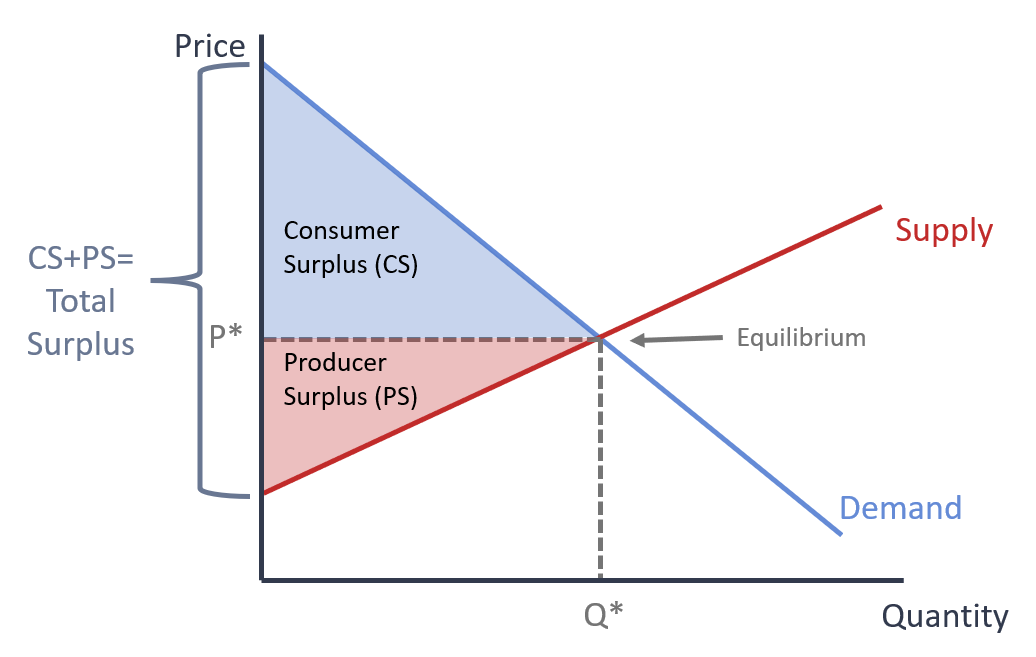

In its most basic terms, consumer welfare refers to the benefits individuals derive from consuming goods and services. Graphically, as shown in Figure 1, it is the area under the demand curve and above the price (shaded in blue). Producers also have a level of surplus (shaded in red). When a market is in equilibrium, the total level of surplus is maximized and is the sum of the consumer surplus and producer surplus.

Figure 1

Figure 2 illustrates an anticompetitive practice or merger that enables a firm to raise prices from P* to the monopoly price, Pm. The firm’s ability to raise prices coincides with reduced output from Q* to Qm.

Figure 2

The darkened border surrounding part of the new level of producer surplus is the share that was transferred from the consumer to the producer. This market structure also introduces lost economic surplus, called deadweight loss (DWL), shown in yellow. This lost surplus arises when the firm can raise prices from the equilibrium price, leading to fewer consumers being able to consume the good or service. This loss of consumer surplus was the focal point of Bork’s work, which led to the current foundation of antitrust law.

Antitrust litigation targeting a specific business practice or merger can employ a diverse set of economic models to estimate and forecast immediate and long-term effects on innovation, quality, price, and quantity. Economists can use existing market data — including but not limited to price, sales, and input costs — and couple them with survey data, retrospective analyses of past antitrust cases, and other pertinent information to estimate the supply and demand curves before (Figure 1) and after (Figure 2) the business practice or merger in question was in application. Moreover, these economic models are not static. They are constantly being refined and tested for their effectiveness. Using economic tools, the consumer welfare standard is something that is measurable and consistent.

Critics of Bork’s “The Antitrust Paradox” allege that he used the term “consumer welfare” as a mask for “total welfare,” meaning he was unconcerned with how welfare was distributed between consumers and producers, only that total welfare was maximized. Senior professor of law at the University of Michigan Daniel A. Crane noted, however, that “Bork’s arguments for a consumer welfare goal were tied to his argument that the antitrust laws were intended to promote efficiency. In The Antitrust Paradox’s introduction, Bork began to build his case that ‘[b]usiness efficiency necessarily benefits consumers by lowering the costs of goods and services or by increasing the value of the product or service offered.’” Crane emphasized that “Bork expressly equated the concerns with consumer welfare with ‘restriction of output.’” [11] This concern is consistent with what is portrayed in Figure 2.

Crane asserted that the distinction between total efficiency and consumer welfare “has received little play in judicial decisions, confirming Bork’s argument that the distinction is unimportant in most antitrust cases.” He cites the Ninth Circuit that “explicitly tied consumer welfare to allocative efficiency… the Ninth Circuit held that ‘allocative efficiency is synonymous with consumer welfare’ and that ‘[c]onsumer welfare is maximized when economic resources are allocated to their best use, and when consumers are assured competitive price and quality.’” [12]

While Bork’s indented definition of the term “consumer welfare” will likely stir ongoing debate, in practice it makes no discernable difference. Bork and other legal scholars successfully transformed antitrust law into an objective undertaking with a consistent, measurable condition.

Back to the Future: Critics of the Consumer Welfare Standard

Recently, there has been a growing movement challenging the legitimacy of the consumer welfare standard as the guiding principle of antitrust law.

In a March 2019 hearing of the Senate Judiciary Committee, former Secretary of Labor Robert Reich testified that “Antitrust is – or should be – about more than welfare economics. The problems it should be addressing go far beyond helping individual consumers get the best possible deal for themselves.”[13]

This sentiment, known as the “New Brandeis” philosophy, has been gaining momentum. The movement is named after Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis for his critiques of “bigness” and economic concentration. [14],[15]

Such ideas inform numerous pieces of recently proposed antitrust legislation, including the American Innovation and Choice Online Act[16] and the Prohibiting Anti-competitive Mergers Act of 2022.[17] Both bills include a firm’s market capitalization, or firm size, as a determinant to whether it is subject to the proposed law.

Subscribers to this philosophy include FTC Chair Lina Khan. In her publication titled “Amazon’s Antitrust Paradox,” Khan writes that “Focusing antitrust exclusively on consumer welfare is a mistake.” She continues, “…focusing on consumer welfare disregards the host of other ways that excessive concentration can harm us – enabling firms to squeeze suppliers and producers, endangering system stability (for instance, by allowing companies to become too big to fail), or undermining media diversity, to name a few.” She also asserts that antitrust laws “were enacted to safeguard…lower income and wages for employees, lower rates of new business creation, lower rates of local ownership, and outsized political and economic control in the hands of a few.”[18]

Proponents argue that antitrust enforcement agencies should look beyond the effects business practices have on consumers and instead use antitrust policy to promote other social goals, including mitigating depressed employee wages, minimizing inequality, limiting harms to competitors, and preventing the rise of big firms that have amassed political power. In other words, this movement calls for a “fairness” standard–but fairness is subjective. Fairness cannot be measured using economic tools and data. Replacing the consumer welfare standard with one of fairness threatens to worsen economic outcomes for consumers and risks slowing innovation and economic growth.

Advocates of this school of thought also believe current antitrust enforcement overlooks important factors such as innovation and quality and overemphasizes price. Yet innovation, quality, the availability of substitutes, and other factors affect the demand curves found in Figure 1 and Figure 2. A shift in the demand curve will impact consumer welfare and is, therefore, reflected in the consumer welfare standard.

Conclusion

Antitrust law and practice have transformed over decades from a subjective way to protect competitors to relying on the consumer welfare standard as the backbone of antitrust policy for nearly 40 years. The consumer welfare standard provides a consistent basis on which antitrust law is implemented and uses economic analysis and empirical evidence to facilitate a consistent and objective application of antitrust jurisprudence. Using antitrust law to pursue other social policies risks creating uncertainty, stifling innovation, and slowing economic growth.

[1] https://www.ftc.gov/advice-guidance/competition-guidance/guide-antitrust-laws/antitrust-laws

[2] https://arizonastatelawjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Wright-et-al.-Final.pdf

[3] Id.

[4] Id.

[5] Id.

[6] https://www.wlrk.com/webdocs/wlrknew/AttorneyPubs/WLRK.26396.18.pdf

[7] https://arizonastatelawjournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/Wright-et-al.-Final.pdf

[8] Id.

[9] https://repository.law.umich.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2549&context=articles

[10] https://www.justice.gov/atr/horizontal-merger-guidelines-08192010

[11] Id.

[12] Id.

[13] https://www.judiciary.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Reich%20Testimony.pdf

[14] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/ftcs-shifting-view-on-competition-policy-and-the-outlook-for-2022/

[15] https://www.pbwt.com/antitrust-update-blog/a-brief-overview-of-the-new-brandeis-school-of-antitrust-law

[16] https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/senate-bill/2992/text

[17] https://www.warren.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/SIL22464.pdf

[18] https://www.yalelawjournal.org/note/amazons-antitrust-paradox