Research

November 28, 2017

Market Distortions Caused by the 340B Prescription Drug Program

Executive Summary

Twenty-five years after Congress created the 340B Drug Pricing Program, policymakers are actively considering important reforms. While the program is rooted in good intentions, it suffers from a lack of much-needed oversight, resulting in several problems. Rapid expansion of the program in recent years is adversely affecting patient access to community-based, affordable health care, in direct contradiction to the program’s mission. Patients are too often not benefitting from the mandatory discounts provided under the program. The amount of charitable care provided by hospitals has declined considerably in recent years, despite being one of the primary reasons for establishing the program. Reforms are needed to ensure program integrity and sustainability.

Introduction

The 340B Program was created to help ensure that uninsured and low-income individuals have access to prescription drugs. Congress created this new program after another federal program—the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program—caused drug manufacturers to pare back dramatically their charitable donations of such medicines.[1] Since its creation, the 340B Program has expanded considerably. Part of this expansion is due to an outdated eligibility threshold for hospitals, which makes hospitals more likely to qualify for 340B as they treat fewer uninsured patients and more insured patients. As more providers become eligible for the program’s mandatory discounts and the availability of those discounts spreads beyond the low-income and uninsured individuals the program was designed to help, the health care market grows more distorted, adversely affecting more than just prescription drug prices.

The House Energy and Commerce Committee recently held a hearing examining the current status and impact of the 340B Program. During that hearing, lawmakers expressed concerns with the program’s rapid growth and lack of oversight as well as the resulting negative consequences throughout the health care market.

Background

If a drug manufacturer wants to have its drugs covered by Medicaid, it is required to participate in both the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program and the 340B Drug Discount Program. The Medicaid Drug Rebate Program requires drug manufacturers to provide rebates for drugs prescribed to Medicaid beneficiaries such that Medicaid is entitled to a drug’s “best price” among most private and public payors (with certain government program exceptions).[2] The 340B Program requires drug manufacturers to provide discounts for all of their covered outpatient drugs purchased by an eligible health care facility for any “qualified patient.” The mandatory discount for each drug is in the form of a ceiling price, set by a statutory formula tied to the value of the Medicaid rebate. The discount can be so large that it results in a price of zero or even a negative price; in these cases, manufacturers have been instructed to use the “penny pricing policy” and set the price at one cent.

There are no rules regarding how the savings obtained through this discount must be used, although there are two explicit prohibitions for participating entities. The first is known as “diversion”: 340B-purchased drugs may not be diverted to ineligible patients.[3] The 340B Program defines a “qualified patient” so broadly, though, that almost any patient treated at a qualifying “covered entity” is eligible.[4] The second prohibition is on obtaining “duplicate discounts” for a 340B drug. This would occur if the covered entity purchases a drug at the discounted 340B price, provides such drug to a Medicaid patient, and then submits a drug claim (or allows the claim to be submitted on its behalf) to the state Medicaid agency to bill the manufacturer under the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program.[5] However, because there are no requirements that the discount be passed on to the patient or her insurer, 340B providers may retain the full amount of the discount, which averages at least 22.5 percent of the average sales price.[6]

Growth in the Program

The types of entities eligible to participate in the 340B Program has expanded several times since the program’s inception, most recently through the Affordable Care Act (ACA). The ACA expanded 340B even while allowing an estimated 20 million individuals to gain health insurance coverage, which should have decreased the need for this program.[7] Eligible facilities now include multiple types of federally-funded health centers and specialized clinics, as well as children’s hospitals, critical access hospitals, disproportionate share hospitals (DSH), rural referral centers, sole community hospitals, and free-standing cancer hospitals.[8]

After the first 13 years of the 340B Program, only 583 hospital organizations participated.[9] The repeated eligibility expansion resulted in the number of participating hospitals growing to more than 2,000 by 2014, accounting for more than 45 percent of all acute care hospitals.[10] The continued growth, along with the thousands of federally funded health centers and clinics that also participate in the Program, brings the total number of unique covered entities to more than 12,000, as of 2016.[11] This growth is largely because of the financial incentives for participating entities and the inappropriate metric used—the DSH percentage—to determine an entity’s eligibility, as explained here.[12]

Hospitals’ adoption of “child sites” has further fueled this expansion. Each participating hospital may own multiple facilities, each of which qualifies as a participating entity, even though on its own the facility may not qualify. When accounting for the child sites of all the participating hospital organizations as well as the other qualifying entities, there were more than 42,000 340B sites as of November 2017, including nearly 19,000 DSH sites.[13]

This map shows the number of 340B entities in each state, as of November 2017.

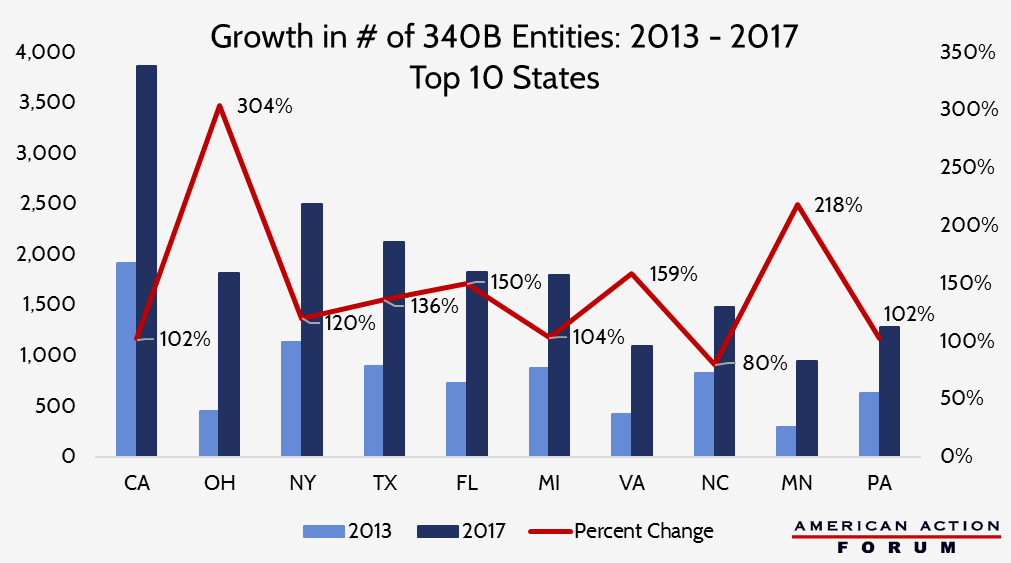

The chart below shows the ten states which have seen the greatest increase in the number of 340B entities over the past four years.

Changes to regulatory guidance in March 2010 permitted entities to expand the reach of the program even further through the use of contract pharmacies. This allows entities to contract with multiple outside pharmacies to dispense 340B drugs to eligible patients.[14] The growth has been tremendous: in just three years, the percentage of covered entities using contract pharmacies under 340B more than doubled from 10 percent to 22 percent; the number of unique pharmacies with which they contracted grew 770 percent; and the total number of such contracts grew 1,245 percent.[15] Analysis published by the Drug Channels Institute found that the number of contract pharmacy locations had grown to nearly 20,000 by 2017. Four large, for-profit national chains make up 60 percent of these pharmacies: Walgreens (32 percent), CVS (10 percent), Walmart (9 percent), and Rite Aid (8 percent).[16]

Not surprisingly, as more and more entities have become eligible for 340B, the share of drugs purchased at a discount has grown as well. The overall share of outpatient brand-name drugs purchased under 340B has reached nearly 8 percent this year, up from 5.4 percent in 2012.[17] Sales under the program have grown at average annual rate of 31 percent since 2013, and reached an estimated $16.2 billion in 2016.[18]

Impact: Perverse Incentives and Unintended Consequences Drive Up Treatment Costs

Hospital Profits From 340B

It has become clear that many entities are taking advantage of the program’s lax rules and lack of oversight. When the Office of the Inspector General (OIG) for the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) investigated 340B DSH hospitals, only one-third reported that they offer the 340B discounted price to uninsured patients.[19] The OIG also found that because Medicare has been reimbursing 340B hospitals at the typical rates without factoring in 340B discounts, in 2013 Medicare Part B and beneficiaries paid 58 percent more than the ceiling price for 340B drugs. For 35 drugs, the beneficiary’s 20 percent coinsurance alone was greater than the acquisition cost of the drug. The difference between the acquisition cost and the Part B reimbursement rate for five high-cost cancer drugs examined by the OIG among non-340B entities was always less than $1,000, while the spread for the same drugs at 340B entities ranged from nearly $6,000 to more than $13,000.[20] One study found that hospitals could make a roughly 500 percent profit off of a 340B drug relative to what the manufacturer who invented and produced it would earn.[21] In total, the difference between the hospitals’ acquisition cost and the reimbursement amount allowed hospitals to retain approximately $1.3 billion in 2013 from 340B discounts alone.[22] The rule issued by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) in November 2017 is an attempt to change this disparity and ensure that taxpayers and Medicare beneficiaries actually do benefit from this mandatory discount.

Because of the large discounts, providers also lose the incentive to prescribe lower cost medicines. This leads to higher costs for the insurer (or taxpayer in the case of Medicare or Medicaid) and higher cost-sharing for patients. Studies have found that 340B hospitals prescribe more high-cost drugs and more drugs overall. One study found that, among the top five therapeutic categories, the rate at which 340B entities or their contract pharmacies dispense generic drugs is significantly lower for 340B prescriptions than all other prescriptions in the same therapeutic class.[23] A report from the Government Accountability Office (GAO) found that per beneficiary expenditures for drugs covered under Medicare Part B were higher for patients at 340B DSH hospitals than non-340B hospitals, even after accounting for the patients’ health status.[24]

While the intent of the 340B Program was to provide participating entities with a greater ability to provide more charity care, hospitals are under no obligation to use the funds derived from the program for charity care. Only 24 percent of 340B hospitals, which represent 45 percent of all hospital beds, provide 80 percent of all charity care delivered by 340B hospitals.[25] Nearly 40 percent of 340B DSH hospitals provide charity care equal to less than one percent of their total patient costs.[26] Only 42 percent of tax-exempt, non-profit hospitals informed patients, according to one study, “of their eligibility for charity care before attempting to collect medical bills and only 29 percent had begun charging uninsured and under-insured patients rates equivalent to private insurance and Medicare rather than standard, higher chargemaster rates.”[27] A follow-up study found that “only 37 percent of 340B hospitals limited their charges for patients who were eligible for charity care to amounts generally billed to insured patients,” and “less than 62 percent… regularly notified patients of their potential eligibility for charity care before initiating debt collection.”[28]

Conversely, a recent change in statute created a discrepancy that disadvantages certain (mostly rural) hospitals and the patients they serve. Section 2302 of the ACA excludes drugs designated by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for treatment of a rare disease or condition from being available for purchase at the discounted 340B price solely by children’s hospitals, free-standing cancer hospitals, critical access hospitals, rural referral centers, or sole community hospitals; other 340B entities do not face such an exclusion.[29] It is important to note that such a designation may be provided to a drug that has already been approved for a common condition if the manufacturer is seeking approval for a new indication for a rare disease. There are 450 such drugs which have been approved by the FDA, but there are currently more than 4,300 drugs that have been “designated” and are thus unavailable for the discount at these particular hospitals.[30]

Provider Consolidation and Increased Costs Beyond Prescription Drugs

The 340B discount incentivizes hospitals to acquire physician practices and make them “child sites” in order to increase the number of drugs that can be purchased under 340B, as the evidence above shows. This consolidation reduces the number of community practices and consequently drives up the cost of care for all services at those facilities, relative to the cost of the same services provided in non-hospital-owned physician offices. Studies have shown that consolidation among hospitals and other health care facilities leads to higher costs at hospitals, often by as much as 20 percent and sometimes by as much as 40 percent.[31]

The loss of independent community oncologists is driving up the overall cost of cancer care, contributing to our unsustainable national health care expenditures. The actuarial firm Milliman found that the percentage of chemotherapy infusions delivered to Medicare beneficiaries in hospital outpatient departments (HOPDs) increased from 15.8 percent in 2004 to 45.9 percent in 2014, with the proportion of these infusions occurring in 340B HOPDs increasing from 3 percent to 23.1 percent.[32] This led to estimated increased expenditures of more than $4,000 per Medicare beneficiary.[33]

The impact on cost is not exclusive to the Medicare population, either. The Milliman study found that infusions delivered to commercially insured individuals in HOPDs rose from 5.8 percent to 45.9 percent during the same period. This site of care change translated to increased costs of up to 40 percent per day.[34] A study by the Moran Group found that when treated in HOPDs, a patient was on chemotherapy treatment 9 to 12 percent more days, compared with those treated in a physician office. Thus, for patients receiving 12 full months of chemotherapy, Avalere found treatments in HOPDS cost 53 percent more than the same treatment in a physician office.[35] Besides the increased cost, patients spend more days in treatment, rather than at home, negatively affecting their quality of life.

Negative Impact on the Non-Target Population

The discounts mandated by the 340B Program and other government regulations may also be responsible for the steady climb in the list price of prescription drugs. Just as private insurers pay more to compensate for Medicare and Medicaid’s low payments, the 340B program has grown so large for certain drugs that their prices are likely climbing as a result of 340B discounts, forcing the rest of the population to subsidize the cost of these discounts.[36]

Reforms Needed

The Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) and drug manufacturers have been permitted since the program’s inception to audit 340B entities’ records if there is suspicion of either diversion or duplicate discounts. Though, manufacturers face severe limitations and must bear the costs of such audits.[37]

At the recommendation of the GAO after it found the possibility of widespread non-compliance, HRSA began conducting risk-based audits of covered entities in 2012.[38] In fiscal year 2016, 76 percent of 340B DSH hospitals that were audited were found to have at least one adverse finding and 41 percent had multiple adverse findings.[39]

Increased use of contract pharmacies has led to further integrity problems in the 340B Program. The OIG found that contract pharmacies complicate entities’ efforts to prevent both duplicate discounts as well as diversion of 340B drugs to ineligible patients. The OIG found that most entities do not conduct all of the recommended oversight activities, and one-fifth of those studied do not have any method in place to prevent duplicate discounts from occurring.[40]

While not every entity is abusing the program and taking advantage of its patients, the preponderance of evidence shows a clear need for significant reform and stronger oversight to ensure program integrity. Currently, only federally funded health centers and clinics are typically required to disclose publicly how they use the savings received from the 340B Program discounts. Hospitals should face similar obligations. Alternatively, 340B hospitals should be required to pass the savings directly to the qualifying patients. Hospitals claim the savings they receive are put to good use, and this is true to a degree.[41] Taxpayers, however, deserve to know that the tax benefit received by these not-for-profit hospitals is justified. Once these rules are updated, penalties for non-compliance must also be enhanced. The current response—temporary ineligibility—does little to deter bad actors.[42]

Another reform should focus on eligibility for the program. The metric for determining an entity’s eligibility for the program should be adjusted to ensure participating hospitals are primarily serving the targeted beneficiaries. The current definition is based on the share of low-income, Medicare and Medicaid inpatients at a hospital, but the program provides a discount for drugs provided to outpatients and is intended to be used for uninsured individuals which, of course, does not include Medicare and Medicaid beneficiaries. More, the calculation does not include the percentages of patients at hospitals’ child sites, which further skews the eligibility metric. This mismatch results in many entities inappropriately benefitting while other entities with much greater amounts of charity care do not. Along these same lines, a clearer and stricter definition of an eligible patient is sorely needed. The current definition is too broad and allows for many more drugs to be obtained at a discount than originally intended.

Finally, HRSA needs both more authority to promulgate regulations that will bring the program in line with its roots as a safety net program and additional resources to provide sufficient oversight. HRSA does not have the authority to require hospitals to report the amount of funds they generate from the Program or how those funds are spent. HRSA also does not have the authority to share ceiling prices with state Medicaid programs, so that the states may ensure they are not paying duplicate discounts.[43] Use of a 340B claim identifier could likely help in this regard. Additionally, despite there being more than 12,000 covered entities and 7,000 contract pharmacy arrangements, HRSA has only 22 full-time employees dedicated to overseeing the 340B Program, primarily due to a lack of funds and direct hiring authority.[44]

Conclusion

It is no secret that the 340B Program no longer seems to be serving its intended purpose and warrants substantial reform. While the program was created to resolve an unintended consequence of the Medicaid Drug Rebate Program, it has created its own unintended consequences. The program suffers from a lack of appropriate standards for program eligibility, clear guidance and requirements regarding the use of savings generated, and necessary program oversight to ensure participants are held accountable and the targeted patients actually receive a benefit. Congress should reform the 340B Program to restore its original intent, ensure program integrity, and eliminate the harmful market distortions caused by it. Without such reforms, the program is unsustainable and the rest of the health care market will continue to suffer.

[1] https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE100/PE121/RAND_PE121.pdf

[2] https://www.medicaid.gov/medicaid/prescription-drugs/medicaid-drug-rebate-program/index.html

[3] 42 U.S.C. § 256b(a)(5)(B)

[4] https://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/FR-1996-10-24/pdf/96-27344.pdf

[5] 42 U.S.C. § 256b(a)(5)(A)(i)

[6] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[7] https://www.rand.org/content/dam/rand/pubs/perspectives/PE100/PE121/RAND_PE121.pdf

[8] http://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF02/20171011/106498/HHRG-115-IF02-20171011-SD002.pdf

[9] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[10] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/may-2015-report-to-the-congress-overview-of-the-340b-drug-pricing-program.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[11] https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2017/05/19/2017-10149/340b-drug-pricing-program-ceiling-price-and-manufacturer-civil-monetary-penalties-regulation

[12] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/reforming-340b/

[13] https://340bopais.hrsa.gov/coveredentitysearch

[14] 75 Fed. Reg. 10272, 10274–10278 (March 5, 2010)

[15] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-13-00431.pdf

[16] http://www.drugchannels.net/2017/07/the-booming-340b-contract-pharmacy.html

[17] https://www.thinkbrg.com/media/publication/928_Vandervelde_Measuring340Bsize-July-2017_WEB_FINAL.pdf

[18] http://www.drugchannels.net/2017/05/exclusive-340b-program-hits-162-billion.html

[19] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-13-00431.pdf

[20] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-14-00030.pdf

[21] http://www.drugchannels.net/2017/04/latest-data-show-that-hospitals-are.html

[22] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-12-14-00030.pdf

[23] http://www.drugchannels.net/2014/11/new-walgreens-data-verifies-that-340b.html

[24] http://www.gao.gov/assets/680/670676.pdf

[25] http://340breform.org/userfiles/May%202016%20AIR340B%20Avalere%20Charity%20Care%20Study.pdf

[26] http://340breform.org/userfiles/May%202016%20AIR340B%20Avalere%20Charity%20Care%20Study.pdf

[27] http://www.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/NEJMp1508605

[28] https://www.thinkbrg.com/media/publication/789_Vandervelde_Hospital_Charity_Care_Compliance_Trends.pdf

[29] http://housedocs.house.gov/energycommerce/ppacacon.pdf

[30] https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/program-requirements/orphan-drug-exclusion/index.html

[31] https://www.rwjf.org/content/dam/farm/reports/issue_briefs/2012/rwjf73261

[32] http://www.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/2016/trends-in-cancer-care.pdf

[33] http://www.milliman.com/uploadedFiles/insight/2016/trends-in-cancer-care.pdf

[34] https://www.communityoncology.org/UserFiles/Moran_Cost_Site_Differences_Study_P2.pdf

[35] https://www.communityoncology.org/pdfs/avalere-cost-of-cancer-care-study.pdf

[36] R. Conti and M. Rosenthal, “Pharmaceutical Policy Reform — Balancing Affordability with Incentives for Innovation,” N Engl J Med 2016; 374:703-706.

[37] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/256b

[38] https://www.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/opa/programrequirements/policyreleases/auditclarification030512.pdf

[39] https://www.hrsa.gov/opa/program-integrity/audit-results/fy-16-results.html

[40] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-05-13-00431.pdf

[41] http://blog.aha.org/post/171010-report-misses-mark-on-340b-program-

[42] https://www.340bhealth.org/340b-resources/340b-program/overview/

[43] https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/256b

[44] http://docs.house.gov/meetings/IF/IF02/20171011/106498/HHRG-115-IF02-20171011-SD002.pdf