Research

October 6, 2025

Analyzing the Effects of the OBBB’s Student Loan Limits on Tuition

Executive Summary

- The One Big Beautiful Bill, signed into law July 4, contains provisions to lower the borrowing limits of federally provided student loans beginning July 1, 2026.

- The reform represents a small step toward better management of taxpayer exposure to the student loan program, and lowering borrowing limits may also reduce the rate at which tuition for higher education increases.

- This research analyzes the effects that the new loan limits would likely have on tuition prices and finds that while reductions in undergraduate tuition will likely be small, we can expect graduate and professional program tuition to decline more significantly, since the law takes aggressive measures to reduce loan limits for these programs.

Introduction

The One Big Beautiful Bill (OBBB), signed into law July 4, contains provisions to lower the borrowing limits of federally provided student loans beginning July 1, 2026. The reform represents a small step toward better management of taxpayer exposure to the student loan program, and lowering limits may also reduce the rate at which tuition for higher education increases.

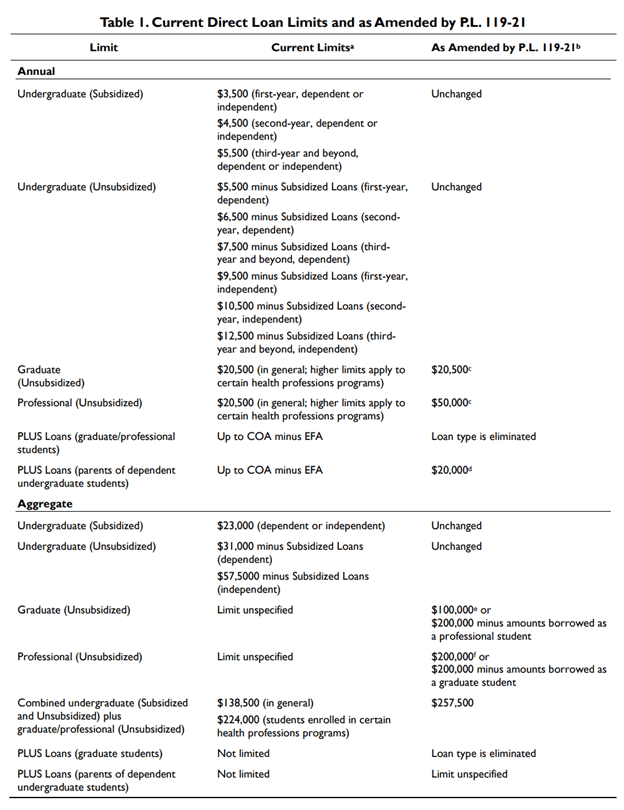

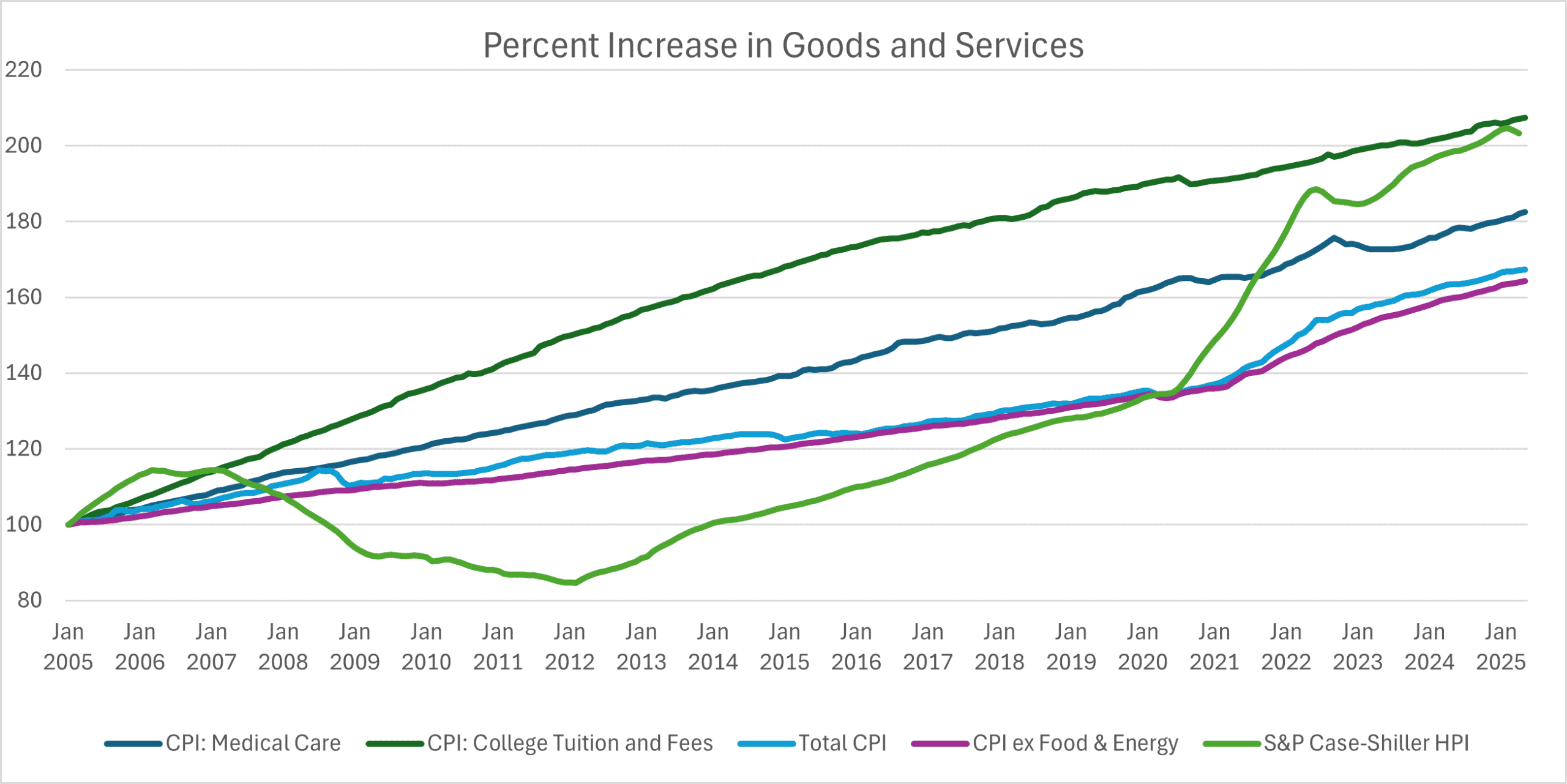

Intended to save taxpayer dollars and control the cost of higher education, the OBBB makes the following notable changes to the borrowing limits of federally provided student loans beginning July 1, 2026: establishes a $257,000 combined lifetime aggregate limit for all loans, adds annual and lifetime caps to Parent PLUS,, terminates Grad PLUS loans, and lowers the aggregate maximums to $100,000 for graduate programs and $200,000 for professional programs.

The wide availability of federal student loans and their associated borrowing limits have long been a concern for policymakers, as they are thought to play a role in the increasing cost of college. In 1987, then-secretary of the Department of Education William Bennett noticed that as the expansion of student financial aid increased, so did tuition. Since then, the postulation that the greater availability of federal student loans increases tuition has been named the “Bennett Hypothesis” and widely studied. Most of the literature has indeed found a positive correlation between the availability of federal student loans and tuition. The research regarding the precise degree to which federal loan availability impacts tuition, however, varies greatly.

This research analyzes the effects that the new federal student loan limits would have on tuition prices for undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs by incorporating the theoretical framework of the Bennett Hypothesis and using the available literature to estimate the degree to which tuition may be reduced. Reductions in undergraduate tuition would likely be small because the law does not change these borrowing limits, except for capping Parent PLUS loans. Since the law takes more aggressive measures to reduce loan limits for graduate and professional programs, tuition for these programs would likely be reduced more significantly.

Changes to Federal Student Loan Limits in the OBBB

Currently, the federal government places both annual and aggregate limits on federal student loans and uses the cost of attendance (COA) to determine how much funding a student is eligible for.

Annual limits cap the amount a student may borrow in a single academic year. Aggregate limits, on the other hand, cap the cumulative amount of outstanding loan principle a student may owe in non-PLUS loans. Therefore, students who are later in their academic career, such as graduate or professional students, are more likely to reach the aggregate loan limit than those earlier in their academic careers.

The OBBB makes several significant changes to the amount a student can borrow to finance their higher education, as shown in Table 1.

Source: Congressional Research Service

The OBBB makes relatively mild reforms to the loan limits for financing undergraduate programs, as the law does not change the current limits for subsidized and unsubsidized loans. Furthermore, the amount of aid for which a student is eligible will still be determined by the COA. It does, however, lower the annual limit of Parent PLUS loans – which parents use to help fund their child’s undergraduate program – from the COA minus the estimated financial assistance (EFA) to $20,000. The law also caps the lifetime maximum aggregate of Parent PLUS loans at $65,000.

The law makes more significant changes to the loan limits for graduate and professional programs, as it eliminates Grad PLUS loans, which are loans graduate students use after they have exhausted their direct unsubsidized loans, and reduces aggregate graduate loan limits from $138,500 to $100,000. It also lowers the aggregate limit of professional programs from $224,000 to $200,000.

Furthermore, the law adds a combined $257,000 lifetime maximum aggregate borrowing limit for all programs, excluding Parent PLUS loans. This lifetime maximum counts any federal aid ever borrowed throughout a student’s career “without regard to any amounts repaid, forgiven, canceled, or otherwise discharged on any such loan.”

The Skyrocketing Cost of College Tuition

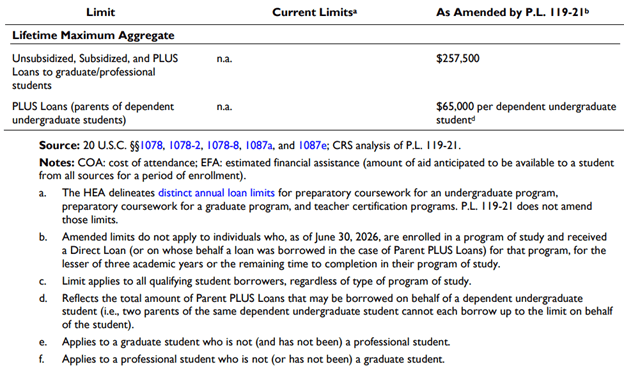

It is no secret that college tuition is skyrocketing. Since 2005, college tuition has increased about 40 percentage points more than the total consumer price index, surpassing both the cost of housing and medical care, as shown in Figure 1.

Source: The Bureau of Labor Statistics

Indeed, college has become so expensive that a 2023 survey showed that 55 percent of individuals who did not enroll or dropped out before graduating did so because of the high cost of tuition. This high cost has also contributed to saddling students with large amounts of student loan debt, with a national total of roughly $1.76 trillion – about $37,088 per borrower.

While there may be several reasons why college tuition is rising, a 2016 study indicates that the expansion of student borrowing limits represents the single largest driver in the increase in college tuition, contributing to about 54 percent of the increase. This rise in price occurs because greater financial assistance from the federal government increases demand for higher education, placing upward pressure on tuition.

The OBBB’s lowering of federal student loan limits reduces the amount of federal aid a student can receive to finance his or her higher education, which could tamp down this upward pressure on tuition.

The Bennett Hypothesis

In 1987, then-secretary of the Department of Education William Bennett wrote a New York Times opinion piece entitled “Our Greedy Colleges” arguing that “increases in financial aid has in recent years have enabled colleges to blithely raise their tuitions, confident that Federal loan subsidies would help cushion the increase.” Thus, the claim that an increase in federal student aid corresponds with an increase in tuition has since been dubbed the “Bennett Hypothesis.”

The Bennett Hypothesis has been subject to much research among academics, and the veracity of the hypothesis is unclear. Most studies, however, appear to find a positive correlation between federal student loan availability and tuition. For example, a 2017 study found that increasing student loan limits have a relatively large impact on tuition, as it estimates that “tuition effects of changes in institution-specific program maximums of about 60 cents on the dollar for subsidized loans and 15 cents on the dollar for unsubsidized loans.” Furthermore, a 2023 study found that graduate “net prices increased by $0.64 per $1 increase in per-student federal borrowing.”

Not all studies, however, have found such strong correlations. For example, education researcher Robert Kelchen has found little supporting evidence for the Bennett Hypothesis as it applies to Grad PLUS loans to fund professional schools, such as business, medical, and law schools.

Other scholars, such as Grey Gordon and Aaron Hedlund, believe that the Bennett Hypothesis holds true, but that the that degree to which tuition rises due to increases in federal student loan limits varies drastically over time, depending on economic and policy conditions.

Despite the lack of consensus on the Bennett Hypothesis and the degree to which federal student loan limits impact tuition, basic economic theory supports the hypothesis that the expansion of federal student aid would place upward pressure on tuition prices, as Veronique de Rugy and Jack Salmon argue:

Government subsidies, which effectively lower the prices of goods or services, inevitably increase demand. Therefore, by subsidizing tuition through federal student aid, the government creates artificially high demand for college degrees, driving tuition prices higher and increasing the overall cost for students and taxpayers. As Bennett hypothesized, if education institutions are receiving greater federal funds and students are still being charged higher tuition and fees, then the educational institutions must be capturing part of the federal aid through increasing tuition.

Impact of Loan Limits on Tuition

If the Bennett Hypothesis holds true, and an increase in borrowing limits increases tuition, it would logically follow that limiting the amount students can borrow would put downward pressure on tuition. Thus, we can expect the loan limits contained in the OBBB to at least blunt the inflationary effect that federal aid has on tuition for undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs.

Since the law changes loan limits differently for undergraduate, graduate, and professional programs, the corresponding tuition rates would be impacted differently as well. This analysis finds that undergraduate tuition would likely be only marginally impacted because the law does not change these borrowing limits, except for capping Parent PLUS loans. Tuition for graduate and professional programs may be more substantially impacted due to the reductions in unsubsidized aggregate limits, the elimination of Grad PLUS loans, and the addition of the new $257,000 lifetime maximum aggregate limit.

Undergraduate Programs

The OBBB would likely do little to blunt the rate at which undergraduate tuition is rising, as it does not change the subsidized and unsubsidized limits. It does, however, make changes to the limits of Parent PLUS loans, as it adds caps these loans at $20,000 annually and adds a lifetime maximum aggregate limit of $65,000 to these loans.

The new Parent PLUS loan limits are likely not going to significantly affect the funding of higher education because parents already borrow well below these limits. Indeed, parents who use these loans to finance their child’s education borrow about $5,225 annually and incur about $29,324 of debt over the duration of their child’s education. Therefore, in accordance with the Bennett Hypothesis, these new borrowing limits on Parent PLUS loans may only yield a small reduction in undergraduate tuition.

It is also likely that the lifetime cap of $257,000 would have a negligible effect on undergraduate tuition because students are unlikely to borrow anywhere near this limit, as graduates of bachelor’s degree programs carry an average debt at graduation of $29,100.

Graduate Programs

While the OBBB trims the edges of the limits for undergraduate programs, it makes more aggressive reforms to the financing of graduate (master’s and PhD) programs. Thus, the law would likely have a more pronounced effect on tuition for these programs.

The OBBB makes two key reforms concerning the financing of graduate programs using federal student aid: lowering the aggregate loan limits from $138,500 to $100,000 and eliminating Grad PLUS loans.

The lowering of the aggregate loan limits from $138,500 to $100,000 could reduce the rate at which graduate tuition is rising, although the degree to which this limit reduction impacts tuition is debatable. As mentioned above, the literature on the impact graduate loans have on tuition varies significantly. Therefore, any estimates should be met with a healthy dose of skepticism. Furthermore, the new limit of $100,000 is still above the average total debt of $88,220 graduate students accumulate when combining both graduate and undergraduate degrees, meaning that the reduced limits could still only yield a marginal effect on tuition. Nonetheless, assuming a passthrough rate, which is defined as “the amount by which net tuition goes up in response to an increase in borrowing limits,” of a conservative 15 percent, compared to Black et al.’s 64 percent, graduate tuition could be reduced by $5,775 to $24,640 before considering other factors and assuming that the average student borrows at the maximum limit. These reductions, however, are not realistic considering that the average annual tuition for private and public graduate programs is $12,120. Therefore, the impact that the reductions in graduate loan limits would be much less than these estimates, although it would still be expected that these new loan limits would have a non-negligible impact on reducing graduate tuition.

Further impacts would be due to the elimination of Grad PLUS loans, which are loans students use to finance graduate education after they have exhausted theirdirect unsubsidized loans. According to a 2023 study that looked at data from 2003 to 2010, “net [tuition] prices increased by $0.75 per $1 increase in average per-student Grad PLUS loans.” Considering that students who use Grad PLUS loans took out an average of $32,000 of these loans last year, and that about one in five master’s graduates used these loans, using the above figures, annual tuition for graduate programs could be reduced by up to $4,800 with the termination of these loans, holding other factors constant and before considering the effects of the other loan limits.

In addition to the above limits, the lifetime maximum aggregate of $257,000 would not likely have a significant impact on tuition because graduate students, as mentioned above, incur an average of about $88,220 of debt, only a fraction of the law’s new lifetime aggregate limit.

Professional Programs

The research concerning the relationship between borrowing limits and tuition varies most drastically for professional programs, such as law and medicine. Some researchers, such as Kelchen, believe that the passthrough rate for these professional programs approaches 0. Others, as mentioned above, argue that it is closer to 64 percent. By applying the 64-percent passthrough rate to the loan limit difference of $24,000, the new aggregate loan limits could reduce annual tuition by up to $15,360, assuming students borrow at the maximum limits.

In addition to the effects from the $24,000 reduction in aggregate limits, the law’s new lifetime maximum aggregate limit of $257,000, which considers any debt ever borrowed by a student throughout their academic career, would likely become a relevant factor in the financing of these programs because the average total aid these students borrow approaches or exceeds this limit.. For example, the average debt a dental school graduate incurs, including debt accumulated in undergraduate studies, is about $296,500, which is $39,500 greater than the lifetime aggregate limit. Medical and veterinary graduates also incur debts that begin to approach the lifetime aggregate limit, with medical school graduates incurring about $212,341 worth of debt and veterinary students incurring about $202,647 worth of debt. As such, this new lifetime cap could potentially place additional downward pressure on tuition for professional programs.

Conclusion

The student loan limits contained in the OBBB could help control the skyrocketing cost of higher education. In accordance with the Bennett Hypothesis, as loan limits for higher education decrease, demand for higher education would taper and reduce the rate at which tuition is increasing. Because the OBBB does little to reduce the loan limits for undergraduate programs, as it only caps Parent PLUS loans, it will have little effect on undergraduate tuition. The reduced loan limits could, however, play a larger role in reducing the rate at which tuition is rising at graduate and professional schools.

Regardless of how much of an impact these limits have on tuition rates, the OBBB nonetheless makes a small step toward managing the ever-increasing cost of higher education.