Research

December 8, 2020

Interim Final Rules: Not So Interim

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Three recent rules highlight how agencies can abuse interim final rules (IFRs) to get around the normal notice-and-comment rulemaking process.

- IFRs are intended to be temporary and followed by a finalized, permanent version after a notice-and-comment period.

- This research finds that of significant IFRs issued since November 1993, 61 percent remain in place – meaning they have not been subsequently replaced by either a final rule or another IFR.

- The fact that most significant IFRs are not replaced suggests agencies view their use as a way to shortcut the traditional rulemaking process for their own convenience.

INTRODUCTION

The Trump Administration’s decision to issue three recent controversial regulations as interim final rules (IFRs) has drawn attention to the use of this tactic to rush rules through the regulatory process.

IFRs are intended to be used only where circumstances warrant quick regulatory action. IFRs – as their name implies – are supposed to be temporary. Once public comment is received on an IFR, the issuing agency is supposed to finalize the rule to make it obviously permanent under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA).

As this research finds, however, IFRs are eventually made permanent at an alarmingly infrequent rate, though this rate varies from administration to administration.

RECENT IFRs

Three recent rules published by the Trump Administration highlight how the use of IFRs can be abused. These rules relied on a tenuous connection to the COVID-19 national health emergency to bypass the traditional rulemaking process, where agencies issue a proposed rule, take comment, then finalize the regulation.

The first two rules pertain to visa programs for high-skilled workers, specifically the H-1B, H-1B1, and E-3 visas. The first rule, published by the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) in October, limited the types of occupations that are covered by the H-1B program. The second rule, published simultaneously by the Department of Labor, raised the minimum wage that employers must pay workers in those visa programs.

Both agencies claimed that bypassing the notice-and-comment process before issuing a final rule was necessary because the economic harm caused by COVID-19 required emergency action to protect jobs held by Americans. On December 2, however, a federal judge ruled against the Trump Administration, finding that the rules’ connection to COVID-19 was not strong enough to warrant shortcutting the regulatory process.

A third rule appears to similarly abuse the IFR mechanism. A Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) rule published on November 27 similarly argued that the COVID-19 emergency was sufficient to allow a major change in how Medicare pays for physician-administered, outpatient drugs under Part B to go into effect while the public commented on the rule. The HHS IFR limits the price Medicare pays for the 50 drugs with the highest total program spending to the lowest price paid by the 22 countries with the per capita gross domestic product equal to at least 60 percent of that of the United States. The emergency justification seems exaggerated; prior to the rule being published as an IFR, a proposed version of the rule was under review at the Office of Information and Regulatory Affairs (OIRA) for five months. Only after it was clear the Trump Administration would be ending after one term did HHS deem it to be an emergency measure.

These examples raise questions about past instances where agencies improperly promulgated an IFR, whether they are ultimately made permanent with a subsequent final rule, or another IFR. If IFRs are not made permanent, then the mechanism is being abused for the purposes of subverting proper regulatory procedure.

METHODOLOGY

Previous research into IFRs is relatively thin. The most comprehensive look into the use of these rules was performed in the 1990s by Michael Asimow. Asimow and his researchers examined four separate calendar year quarters of the Federal Register ranging from 1989 to 1997 and counted the number of IFRs, then searched to see if those rules ever became fully finalized. Of the earliest three quarters Asimow found that 46 percent, 42 percent, and 53 percent of IFRs published during those quarters remained in place without finalization. The quarter from 1997 was excepted since it was too recent to give enough time for many of the IFRs to be finalized.

This research takes a different approach. Despite the digitalization of federal rulemaking that has made tracking regulations easier, the Federal Register does not differentiate between IFRs and other types of rules published. A comprehensive review of all IFRs published in the Federal Register over a given time frame is not possible, therefore, and would have to be done in a manner similar to Asimow.

With OIRA’s review of regulations under Executive Order 12,866, however, one can comprehensively examine all IFRs (by Regulation Identifier Number, or RIN) deemed significant enough for OIRA to review, and see which RINs were subsequently reviewed as final rules or supplanted by further IFRs.

This research uses OIRA regulatory review data available at www.reginfo.gov to identify significant rules that were published in the Federal Register and to check if each was ever finalized or if the regulation in place today is still “interim.”

FINDINGS

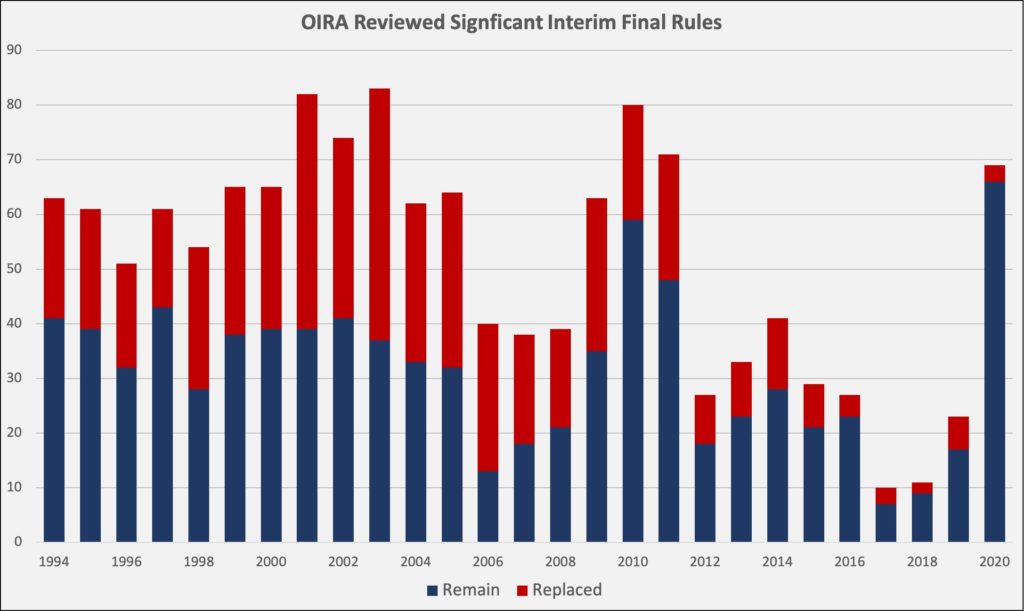

The publicly available OIRA database began tracking whether a rule was an IFR in late 1993, in the first year of the Clinton Administration. A search of all available IFRs whose status is marked as “concluded” returns 1,493 results. Culling those rules that were withdrawn from OIRA review, or never published in the Federal Register, trims the list to 1,392. Searching the regulatory review history of the remaining RINs associated with each of these rules finds that 852 – 61 percent – have yet to be replaced. The chart below breaks down the number of IFR reviews completed by OIRA by year showing how many remain and how many have been replaced, excepting 1993 because it did not include a complete year’s worth of data.

What stands out in the chart are three noticeable spikes in the number of significant IFRs during 2001-2003, 2009-2011, and in 2020. These coincide with responses to three major events likely to justify the emergency nature of IFRs: the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001, the “Great Recession” during 2009-2011, and the COVID-19 pandemic.

There could also be alternate explanations for the first two spikes – both 2001 and 2009 were the first years of the George W. Bush Administration and the Obama Administration, respectively. Administrations may try to enact policies more quickly via IFRs early in their administration, or their predecessors may try to jam through final policy preferences. There is evidence to suggest this is true. Only 26 of the 82 IFRs completed in 2001 occurred after September 11, just a slightly more frequent rate than prior to the attacks. The Trump Administration offers a counter to this explanation due to a low number of significant IFRs prior to a major emergency, though the administration was less conventional than its predecessors.

Another takeaway from the chart is the lack of a trend showing that older IFRs are more likely to be replaced than newer IFRs. Since IFRs are supposed to be replaced, one would expect the earlier years on this chart to be more red than blue, but with few exceptions the opposite is true. This suggests that IFRs are viewed by their issuing agencies more as a workaround for the notice-and-comment process than as temporary measures to be finalized later, which goes against the intent of the APA.

The four administrations were consistent in their rate of significant IFRs as a percentage of all significant final rules issued. The Bush Administration had the highest rate with 18.3, followed by the Clinton Administration (18.1 percent), the Obama Administration (17.2 percent), and the Trump Administration (16.6 percent).

Despite issuing significant IFRs at a slightly higher rate than the other administrations, the Bush Administration was the best at replacing them with more permanent rules. Forty nine percent of its significant IFRs remain in place today, which while high, is still better than the 61, 69, and 88 percent of the Clinton, Obama, and Trump Administrations, respectively. The Trump Administration figure may be inflated due to its limited amount of time in office compared to the others but is currently showing little urgency in finalizing IFRs before its term expires. Just four replacements of the IFRs issued during the administration are currently under review at OIRA.

DATA SUGGEST REFORM IS NECESSARY

The findings align roughly with Asimow’s research from two decades ago. Federal agencies simply do not follow through with making IFRs permanent, as intended in the APA. The use of IFRs have instead become a way to short-cut the rulemaking process, and reform is necessary to restore the process’s integrity.

The simplest solution would be for agencies to make permanent their IFRs once the public comment period is concluded. As the data show, however, the incentives are not aligned to make this a reality. There is no consequence for leaving IFRs unreplaced. It appears a legislative response is necessary to address the problem.

Congress could amend the APA to add a mechanism to incentivize agencies to complete the rulemaking process on IFRs. One way to do this would be to set a universal expiration date on IFRs – such as three years, for example. If an agency fails to finalize an IFR before the expiration date, the IFR ceases to have effect. Another option could include budgetary penalties on agencies that fail to make permanent a sufficient number of IFRs.

CONCLUSION

Recent IFRs highlight how the practice, intended for use in emergencies, can be subverted as a way to shortcut the regulatory process. Research into nearly 30 years of significant IFRs shows that most IFRs are never made permanent, and instead remain as technically interim. Because of a lack of incentives for agencies to make IFRs permanent, Congress would need to increase its oversight on IFR usage and consider a legislative fix.