Research

November 10, 2016

PRIMER: Children Enrolled in Medicaid

There are five broad categories of individuals eligible to receive health care coverage through the Medicaid program. While the exact parameters vary for each group and by state, all beneficiaries must meet some income-threshold, subject to federal minimum requirements for mandatory eligibility groups. Eligible low-income individuals, by category, include children, disabled, aged, adults (specifically, pregnant women and parents), and (with the passage of the Affordable Care Act (ACA) and its Medicaid expansion provision) “newly eligible”/expansion-population adults, who may not have any children.

Differences Among the Beneficiaries

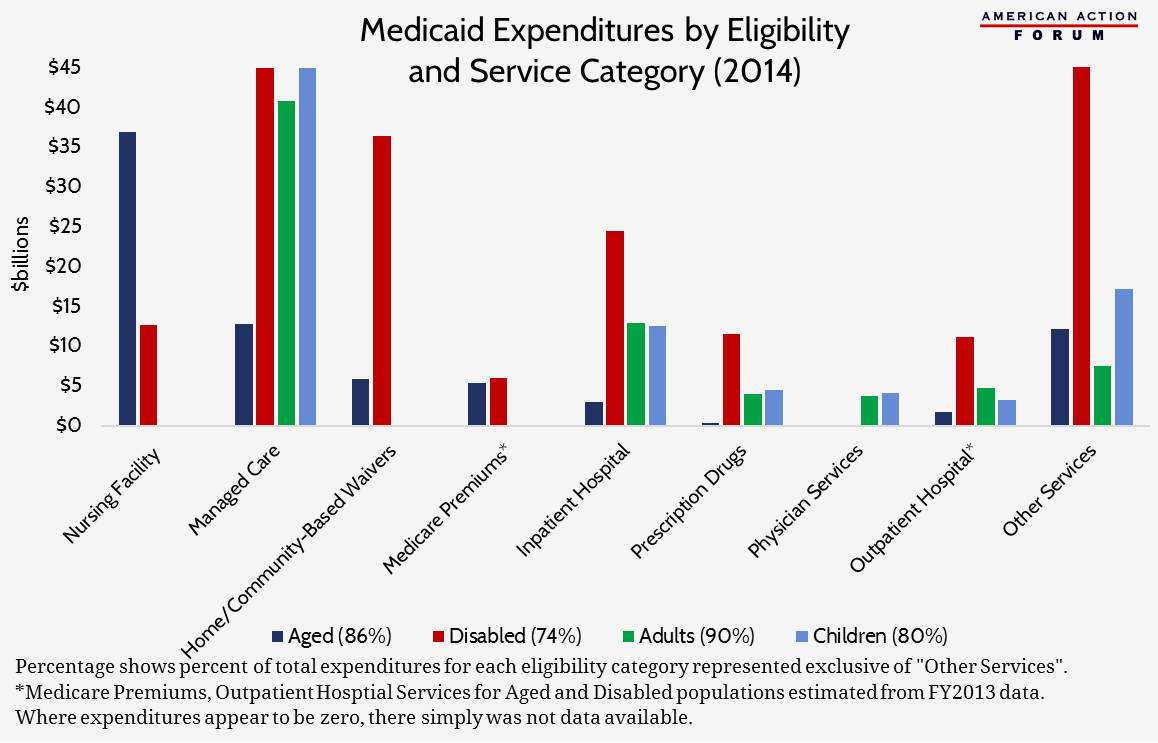

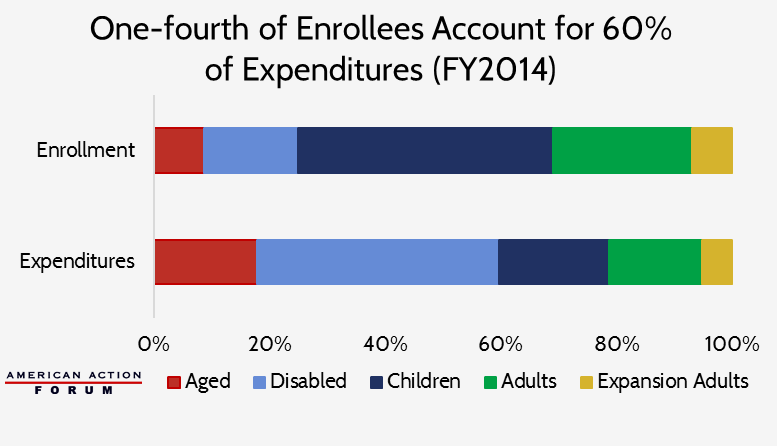

Historical data shows stark differences in expenditure levels and the services used between the various groups enrolled in Medicaid.

The aged and disabled have the highest expenditures. Older individuals, particularly those of low-income, are more likely to have multiple chronic conditions, and individuals with disabilities have complex medical needs which are expensive to provide. In 2014, aged and disabled individuals accounted for only 25 percent of all Medicaid enrollees, yet they were responsible for 60 percent of the program’s expenditures.

Children with Medical Complexity

On average, children are the least expensive Medicaid population on a per beneficiary basis, costing just $3,141 per child in 2014.[1] However, some children suffer from complex medical conditions which cause their expenditures to be extremely high. In 2011, just 5.8 percent of all children covered by Medicaid were found to have a medical complexity (a condition that is both complex and chronic), though these children consumed 34 percent of all health care spending among children in Medicaid.[2] The average annual expenditure for these children was $12,500, nearing that of beneficiaries dually-eligible for Medicare and Medicaid. Nearly half (45.8 percent) of those children had three or more chronic conditions and one-fourth were eligible for Medicaid because of a disability. Thus, roughly 20 percent of these children, or 1.2 percent of all children covered by Medicaid, have three or more chronic conditions, but are not categorized as disabled. This amounts to as many as 442,000 children in 2015.[3]

Overall, inpatient hospital expenditures account for roughly 14 percent of total costs for children in Medicaid. For children with medical complexity (CMC), though, hospital care accounted for 47.2 percent of their health care expenditures in 2011.[4] These children have different needs and require more intensive and more carefully-coordinated care management, much of which must be done between visits in the form of research, phone calls, and consultations with other providers in order to determine the most appropriate course of treatment. However, because current physician reimbursement rates do not compensate providers for care coordination efforts nor time not spent with the patient, providers are not adequately reimbursed for the extra time and effort they put in on behalf of these children. Consequently, proper care management and coordination may not be prioritized, and the children suffer.

Further, because of the unique conditions of these children and highly specialized care they require, many may only be able to access the care they need from out-of-state medical providers. Approximately two-thirds, or 2 million, of the children with medical complexity are covered by Medicaid. By the very fact that they are Medicaid eligible, the families of these children are unlikely to have sufficient resources to travel out-of-state for their care, creating additional challenges to accessing care. Even if they are able, payment for services received by these children out-of-state can often be complicated because Medicaid is funded by both the federal government and the state in which the child resides. Each state Medicaid program sets its own reimbursement rates and may only reimburse providers enrolled within the state. This difficulty accessing and paying for necessary care and providing support for providers close to the child’s home has led to not getting the right care at the right time, as evidenced in the figures provided above, rather than use of more efficient care settings, such as primary, community, and home care.

Possible Solutions

Incentivizing the provision of integrated and coordinated care tailored to the specific needs of these children will provide great benefits and likely reduce costs. In an attempt to address these issues, Congress is considering legislation that would allow states to establish medical homes for these children. Medical homes provide patients with a central access point to their health care, coordinating all of the patient’s care providers and managing all of the patient’s health care needs, including hospital care and prescription drug use. The most robust medical homes are comprehensive and patient-centered, allowing for shared decision-making and accounting for the patient’s and family’s desires and limitations.

Under the proposed legislation, payments would be made to the medical home for the provision of all services needed by the child—which could be similar to a per capita payment for individuals enrolled in managed care plans depending on the risk-based model chosen. Each medical home must, among other things, “coordinat[e] access to the full range of pediatric specialty and subspecialty medical services, including services from out-of-state providers, as medically necessary.” Payments may be tiered based on the severity of the child’s condition(s) or the capabilities of the team of providers. Additionally, the payments may include models based on shared savings, pay-for-performance, or contingency awards. The Administrator of the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) would be responsible for issuing guidance to the states on how to coordinate care and provide payment for services furnished by out-of-state providers.

The legislation would also require the collection and reporting of data regarding the care such children receive. States and providers would develop measures to evaluate the quality of the services provided. The states would provide details as to the number of children with medical complexity and the conditions and severity of their illnesses; the extent of the use of such services; the providers involved in their care, including those treating out-of-state children. All of this information will help providers and policymakers better understand the extent of the problems faced by these children and their families and can be used to develop evidence-based standards of care, which should ultimately improve the outcomes for these children.

Allowing states to establish medical homes for children with medical complexity in a manner that will promote care management and allow better access and coordination as a child travels to out-of-state providers could significantly improve the care received by these children. Further, this type of payment model moves Medicaid to a more time- and cost-efficient, value-based structure, which is a common goal of most health policy experts. Efforts to improve care coordination and treatment options for medically complex children in such a way would both improve the system for the children and families who need it, and would better align the incentives of those hospitals and providers who interact with the federal-state Medicaid program.

[1] 2015 Actuarial Report on the Financial Outlook for Medicaid, Office of the Actuary, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, June 28, 2016.

[2] http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/33/12/2199.abstract

[3] https://www.medicaid.gov/chip/downloads/fy-2015-childrens-enrollment-report.pdf

[4] http://content.healthaffairs.org/content/33/12/2199.abstract