Testimony

March 28, 2017

The Arbitrary and Inconsistent Non-Bank SIFI Designation Process

Chairman Wagner, Ranking Member Green, and members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the opportunity to appear today and share my views on the Financial Stability Oversight Council’s (FSOC) non-bank designation process. And thank you for your work on the report released earlier this month. I’ve found it useful in highlighting and explaining both the procedural and substantive problems with FSOC.

FSOC’s mission is to identify, monitor, and address threats to America’s financial stability. Yet, the current process by which non-bank financial companies are designated as systemically important financial institutions (SIFIs) and the heightened oversight and regulation they fall subject to thereafter, is inherently flawed and risks losing the confidence of the public and policymakers and burdening the economy without any notable benefits. In my testimony, I wish to make three main points:

- FSOC’s process, inconsistent or not, has prioritized designation and regulation of institutions, often arbitrarily, over the identification of activities that pose systemic threats and has done so in a fundamentally flawed manner. I applaud the Subcommittee for making a critical investigation into this process and all its implications.

- Designating a non-bank financial institution as a SIFI is consequential for both the institutions and the institutions’ customers. Those consequences include, but are not limited to, decreased international competitiveness for American companies in the international market and increased costs with decreased benefits for consumers.

- Thus far only insurance companies have been designated as non-bank SIFIs. A good argument can be made for removing FSOC’s authority to regulate those non-bank financial companies, as these companies are already being regulated at the state level. The increased burdens from FSOC’s oversight are unnecessary and provide no additional financial stability.

Let me expand on each in turn.

FSOC’s designation process was authorized by Dodd-Frank. Title I, Subtitle A, of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act (Dodd-Frank Act) established FSOC, outlined the Council’s powers, and introduced factors that must be considered when designating NBFCs as SIFIs. Because banking companies with over $50 billion in assets are automatically considered SIFIs in the Dodd-Frank Act, key issues involving designation revolve around non-banks.

Specifically, Section 113 of the Dodd-Frank Act gives FSOC the authority by two-thirds vote (including the chairperson) to bring a NBFC under increased supervision and regulation by the Federal Reserve Board (FRB) if the Council determines that “material financial distress at the U.S. non-bank financial company, or the nature, scope, size, scale, concentration, interconnectedness, or mix of the activities of the U.S. non-bank financial company, could pose a threat to the financial stability of the United States.”[1] In making that determination, the Dodd-Frank Act lists ten criteria for FSOC to consider along with “any other risk-related factors that the Council deems appropriate.”[2] Given that, FSOC has broad authority statutorily when evaluating companies for SIFI designation. In April 2012, FSOC released a final rule and interpretive guidance on the process it uses to designate SIFIs.[3] The Council recently voted to supplement that process during its February 2015 meeting following an internal review and input from the public and stakeholders.[4]

The three-stage evaluation process FSOC developed is intended to narrow the pool of companies potentially subject to designation by applying specific thresholds based on 11 criteria included in Section 113 of the Dodd-Frank Act. The 11 criteria have been incorporated into six overarching framework categories that FSOC considers: (1) size, (2) interconnectedness, (3) leverage, (4) substitutability, (5) liquidity risk and maturity mismatch and (6) existing regulatory scrutiny.

Table 1 highlights how thresholds in these categories are applied and how scrutiny increases as a company advances through each stage. However, in practice, it is not clear the weight given to certain factors over others or what makes a designation more likely.

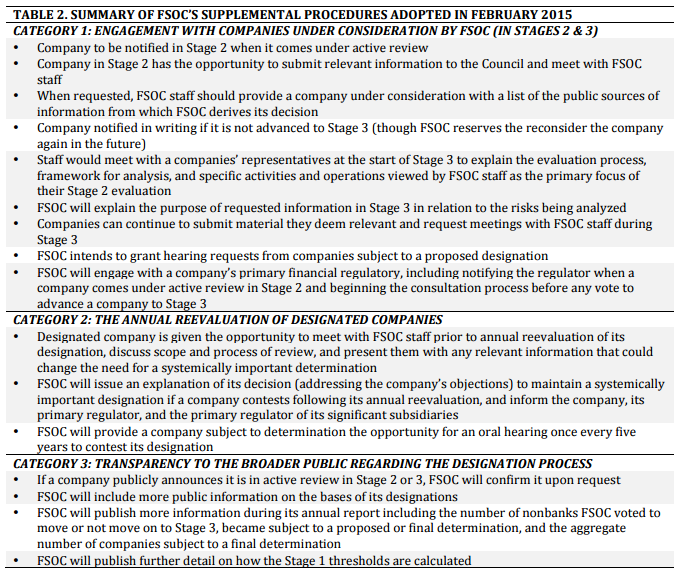

Table 2 includes a summary of all changes adopted in 2015, many of which attempt to address the need for increased transparency and communication. Items shaded in gray are substantially similar to reforms previously highlighted in past work by the American Action Forum.[6][7][8]

Even if FSOC were following the rules and designating NBFCs fairly, consistently and with good reason (which the Committee’s report suggests in not always the case), the process FSOC has developed to designate NBFCs as SIFIs can disrupt markets and impose unnecessary regulatory burdens and costs that outweigh its benefits to the economy. So despite slight improvements made two years ago, FSOC’s process is still fatally flawed (as I have testified before the House Committee on Financial Services previously).[9] The fact that FSOC is using its considerable power with little to no uniformity and reason to designate NBFCs, putting them and their customers at risk of serious financial consequence, is reason to doubt whether FSOC should be able to designate NBCFs at all. It is important to take a look at exactly what those consequences entail.

AAF has noted that FSOC’s regulatory designation “imposes direct costs and risk on the designated institutions. The magnitude of the costs is uncertain, especially given that the specific rules and capital requirements have largely yet to be determined, but it cannot be presumed negligible.” More worrisome is the fact that FSOC’s “two-tiered system will alter competitive dynamics in the insurance sector…Other things being equal, the increased costs of enhanced supervision will reduce their ability to compete effectively, plausibly shifting some amount of business and risk to entities not subject to the additional level of regulation, and destabilizing rather than stabilizing the market. Large banks who compete with each other are all under the same regulatory umbrellas.” Such is not the case with FSOC-designated SIFIs.[10]

The arbitrary and inconsistent designations should also raise questions of regulatory scale, scope, and overreach. At a very basic level, it should be obvious that FSOC’s decisions to regulate insurers, capricious or not, disregard the role that state regulators already play in overseeing insurance companies. As Scott Harrington wrote in a paper for AAF,[11] “[FSOC] largely ignores the historical solvency record, pays little attention to the history of improvements in solvency regulation, and dismisses states’ ability to issue stays on policyholder withdrawals because doing so ‘could’ undermine financial stability during an unspecified crisis. The treatment reflects the notion that the lack of a true consolidated regulator at the state level trumps any argument for the effectiveness of state regulation, including changes in response to the crisis.”

Similarly, given FSOC’s failure to perform a basic cost benefit analysis, it failed to consider even the costs of its macroprudential regulation to consumers of those companies’ products. In a 2013 report[12], Oliver Wyman explains how FSOC’s heightened capital requirements on insurance companies result in increased costs to consumers. The report shows that designated insurers will reduce their capacity or exit the market entirely, leaving the remaining insurers to increase their prices. And in markets with higher barriers to entry with a high market share by the designated insurers, the ability for the undesignated insurers is even greater, leaving consumers with significantly increased costs for the same or fewer benefits. Specifically, the report shows that the annual consumer cost of designating a NBFC as a SIFI could range from $5 billion to $8 billion.

Recommendations and Conclusion

The first obvious fix for FSOC is greater transparency and accountability. FSOC simply cannot continue to arbitrarily designate companies without consequence. Aside from that, the alternative and better approach to developing enhanced supervision to mitigate systemic risk is not to designate specific companies as systemically risky. Rather it is to focus on the underlying activities in different sectors that could lead to systemic risk. If there is sufficient evidence to show that an activity is creating systemic risk without adequate regulatory constraints, then this approach would lead to the development of new regulations governing the activities throughout a sector or across multiple sectors. It would allow bodies like FSOC to focus on underlying risk with systemic potential and would address all entities participating in that particular activity. It would consider systemic risk without an unnecessary attention to potential distress at a single company, thereby better reflecting the potential accumulation of risk across entities. If an activities-based approach had been in effect during the mid-2000s, it’s conceivable that the financial crisis would have been substantially less severe or even inexistent.

Policy debate over systemic risk in asset management has considered the same underlying story for insurance – that some shock could lead to liquidity problems, runs, and liquidations with systemic consequences.[13][14] The Financial Stability Board has moved to an activities-based approach for asset managers, and the FSOC should be doing so as well.[15]

In closing, to quote Scott Harrington, who has written extensively on this issue, “Although the domestic and international insurance SIFI trains have left the station, the U.S. train is currently down to two cars, and there is a long way to go in terms of developing and implementing insurance specific standards for enhanced supervision under Section 113. There is no compelling evidence that any life insurer poses a threat to the financial stability of the United States, and the Section 113 regime is flawed in concept and execution. A better approach would be to return to the station and change destinations. If the United States were to shift towards an activities-based approach for insurers, it might have positive spillover effects globally.”[16] At a minimum, FSOC must conduct its business in a way that is analytically sounder and better grounded in date and regulatory history, with a clear path away from SIFI designation for non-banks.

Thank you, and I look forward to answering your questions.

[1] 12 U.S.C. § 5323 (a)(1).

[2] 12 U.S.C. § 5323 (a)(2)(K).

[3] “Authority To Require Supervision and Regulation of Certain Non-bank Financial Companies; Final Rule and Interpretive Guidance,” 77 Federal Register 70 (April 11, 2012) pp. 21637-21662; https://federalregister.gov/a/2012-8627.

[4] FSOC, “Supplemental Procedures Relating to Non-bank Financial Company Determinations,” (February 4, 2015); http://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/designations/Documents/Supplemental Procedures Related to Non-bank Financial Company Determinations – February 2015.pdf.

[5] “Authority To Require Supervision and Regulation of Certain Non-bank Financial Companies; Final Rule and Interpretative Guidance,” 77 Federal Register 70 (April 11, 2012) pg. 21661; https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2012/04/11/2012-8627/authority-to-require-supervision-and-regulation-of-certain-nonbank-financial-companies.

[6] Satya Thallam, “Reform Principles for FSOC Designation Process,” (November 11, 2014) http://americanactionforum.org/research/reform-principles-for-fsoc-designation-process.

[7] Scott Harrington, “Systemic Risk and Regulation: The Misguided Case of Insurance SIFIs,” (September 20, 2016) https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/systemic-risk-regulation-misguided-case-insurance-sifis/.

[8] Meghan Milloy, “Congress: FSOC is ‘Arbitrary and Inconsistent’,” (March 23, 2017) https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/congress-fsoc-arbitrary-inconsistent/.

[9] Douglas Holtz-Eakin, “FSOC Accountability: Non-bank Designations,” (March 25, 2015) http://americanactionforum.aaf.rededge.com/uploads/files/insights/sbc_testimony_on_fsoc_final.pdf.

[10] id. at Note 8.

[11] id. at Note 7.

[12] Oliver Wyman, “The Consumer Impact of Higher Capital Requirements on Insurance Products,” (April 10, 2013) http://www.responsibleregulation.com/wpcontent/uploads/2013/05/Pricing-impact-study-Oliver-Wyman-April-10-2013.pdf.

[13] FSOC, “Financial Stability Oversight Council Update on Review of Asset Management Products and Activities” (2016) https://www.treasury.gov/initiatives/fsoc/news/Documents/FSOC%20Update%20on%20Review%20of%20Asset%20Management%20Products%20and%20Activities.pdf

[14] Office of Financial Research, “Asset Management and Financial Stability” (September 2013) https://www.financialresearch.gov/reports/files/ofr_asset_management_and_financial_stability.pdf

[15] Financial Stability Board, “Consultative Document – Proposed Policy Recommendations to Address Structural Vulnerabilities from Asset Management Activities,” (June 22, 2016) http://www.fsb.org/wp-content/uploads/FSB-Asset-Management-Consultative-Document.pdf

[16] id. at Note 7.