Testimony

July 27, 2017

The Need for A Balanced Budget Amendment: Testimony to the Judiciary Committee U.S. House of Representatives

Introduction

Chairman Goodlatte, Ranking Member Conyers and members of the Committee, I am

pleased to have the opportunity to appear today. In this testimony, I wish to make

five basic points:

- The federal budget outlook is quite dire, inhibits economic growth, and ultimately raises the real threat of a sovereign debt crisis,

- A debt crisis would impose significant harm to the economy as a whole, and specifically on American families,

- The adoption of a “fiscal rule” would be a valuable step toward budgetary

practice that would address this threat and preclude its recurrence, - A balanced budget amendment to the U.S. Constitution is one such fiscal rule;

one whose very nature would render it an effective fiscal constraint immune

from the forces that have generated a history of Congresses reneging on budgetary targets, and - Recent incarnations of a balanced budget amendment contain provisions that

address some traditional concerns regarding balanced budget requirements.

I will pursue each in additional detail.

The Budgetary Threat

The federal government faces enormous budgetary difficulties, largely due to long-term pension, health, and other spending promises coupled with recent programmatic expansions. The core, long-term issue has been outlined in successive versions of the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO’s) Long-Term Budget Outlook[1]. In broad terms, the inexorable dynamics of current law will raise federal outlays from an historic norm of about 20 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP) to anywhere from 30 to nearly 40 percent of GDP. Spending at this level will far outstrip revenue, even with receipts projected to exceed historic norms, and generate an unmanageable federal debt spiral.

This depiction of the federal budgetary future and its diagnosis and prescription has all remained unchanged for at least a decade. Despite this, meaningful action (in the right direction) has yet to be seen, as the most recent budgetary projections demonstrate.

In June, the Congressional Budget Office released its updated budget and economic baseline for 2017-2027. The basic picture from CBO is as follows: tax revenues return to pre-recession norms, while spending progressively grows over and above currently elevated numbers. The net effect is an upward debt trajectory on top of an already large debt portfolio. The CBO succinctly articulates the risk this poses: “Such high and rising debt would have serious negative consequences for the budget and the nation… Lawmakers would have less flexibility to use tax and spending policies to respond to unexpected challenges. The likelihood of a fiscal crisis in the United States would increase. There would be a greater risk that investors would become unwilling to finance the government’s borrowing unless they were compensated with very high interest rates. If that happened, interest rates on federal debt would rise suddenly and sharply.”[2]

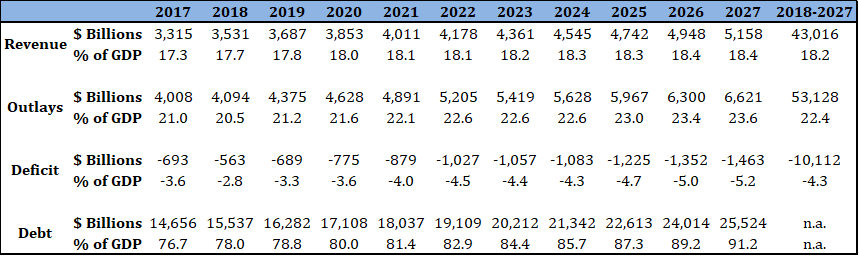

Figure 1: The Budget Outlook by the Numbers

According to the CBO, tax revenue will average above 18 percent of GDP over the next ten years. This is well above the 40-year average of 17.4 percent. The federal government is projected to spend over $53 trillion over ten years, maintaining spending levels 1.9 percentage points above historical levels. Mandatory spending, which comprised 46 percent of the federal budget in 1977, will reach 65 percent in 2027. Interest payments on the debt comprised 7 percent of the budget in 1977 and 6 percent in 2016. These payments will rise to 12 percent of the budget. Debt service payments will reach 2.9 percent of GDP by 2027 – well in excess of the 40-year average of 2.2 percent.

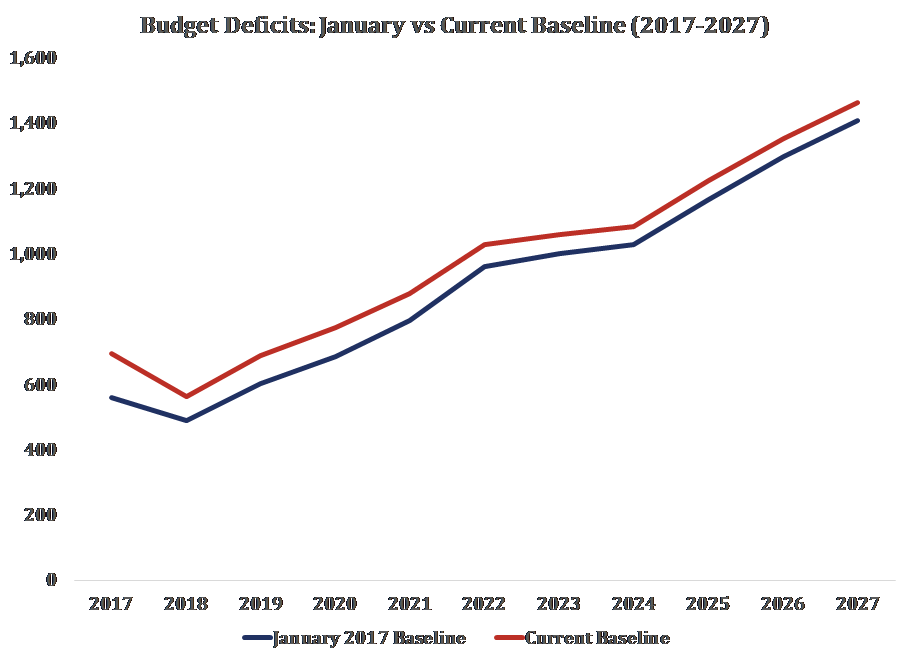

Over 2017-2027, projected deficits will surpass $1 trillion again by 2022. Importantly, the deficit outlook has worsened since CBO’s last estimate by nearly $700 billion.

Figure 2: The Deficit Outlook has Worsened

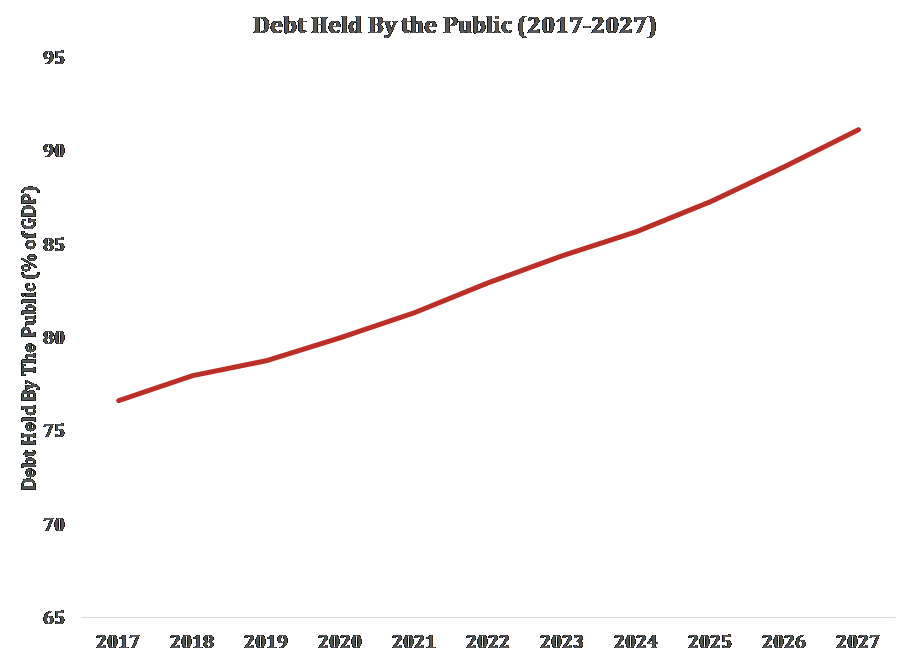

The worsened deficit outlook will raise borrowing from the public over the coming decade. Debt held by the public reached the highest levels since 1950 in FY 2016, reaching 77.0 percent of the economy, while projected to grow to levels not seen since 1947 by the end of the decade.

The Threat of a Fiscal Crisis

As the CBO makes clear, the trajectory of U.S. borrowing would increase the risk of a sovereign debt crisis.

Figure 3: Debt Ultimately on an Upward Trajectory

The trajectory, direction and the magnitude of the current debt outstanding are ultimately the most telling characteristic of the U.S. fiscal path. The widely acknowledged drivers of the long-term debt – health and retirement programs for aging populations, and borrowing costs – will overtake higher than average tax revenue and steady economic expansion. The debt will grow inexorably until creditors effectively refuse to continue to finance our deficits by charging ever-higher interest payments on an increasingly large debt portfolio. This crisis state is more pernicious than mere stabilization of the debt at a high level, which would suppress economic growth, as financing the debt crowds out other productive investment. Instead, unchecked accumulation of debt would precipitate a fiscal crisis that would upend world financial markets and do lasting harm to the nation’s standard of living.

In a hypothetical fiscal crisis, the policy response most readily available to lawmakers would be ill-targeted insofar as it would likely leave untouched the large drivers of the debt itself – health and retirement and entitlement programs. Such programs do not lend themselves to immediate reduction. Accordingly, a fiscal consolidation that was forced by creditors would likely take the form of tax hikes and cuts to discretionary spending. These tax hikes and discretionary spending increases would be sharp and immediately felt.[3]

The nation would also face immediate and steep interest penalties on financing its shorter-term debt portfolio, about $5 trillion, which, all else being equal would also have to be borrowed or absorbed through significant, additional tax increases and spending.

Such an immediate fiscal contraction would have a deleterious effect on the economy discussed in greater detail below. From a purely budgetary perspective, large and immediate tax cuts and spending hikes would reduce growth, and immediately reduce the revenue collected from tax increases. Spending would also increase as certain automatic stabilizers come into force as the economy flags.

Why the Debt Matters to Individuals

A debt crisis has three key features: abrupt and large fiscal consolidations, high interest rates, and weak economic growth. All three have real implications for individuals and families.

The policy response would certainly be visible to individuals. It is difficult to quantify how the reduced budgetary resources would be experienced individually, but there would be clear erosions in defense readiness, education expenditures, and research initiatives. Other more basic services, many of which were recently disrupted during the smaller sequester would be reduced.

With respect to tax policy, a clearer picture can be drawn. According to recent projections, in 2027 the average federal tax rate, which includes payroll and corporate taxes, will be 20.2 percent.[4] A tax increase adequate to achieve an immediate fiscal consolidation percent hike would take that rate up several percentage points. However, it would be very unlikely that a policy response would fall evenly across all taxes and all tax brackets. Rates would have to be commensurately higher as fewer and fewer taxpayers and less of the tax base is exposed to higher rates of taxation. One recent estimate suggests that raising rates on just the 28 percent bracket and above would necessitate a rate increase of 20 percentage points to raise the revenue required if the U.S. needed an immediate fiscal consolidation.[5]

The second distinguishing element of a debt crisis is a high interest rate environment. The U.S. treasury security is the benchmark for the cost of funds, and underpins all manner of consumer financial products. Prime mortgage rates are highly correlated to Treasury notes.[6] Accordingly, one can construct a notional mortgage rate in an extraordinarily high interest rate environment. If 10-year Treasury’s jumped 1000 basis points, today’s prevailing mortgage rate of 3.96 percent would jump to 13.96 percent.[7] For the sake of comparison, at today’s rates, monthly interest and principal payments on a $250,000 home loan would amount to $1,188. At 13.96 percent, payments would jump to $2,954.[8]

The example holds true in other matters of consumer finance, which rely on Treasury securities as benchmarks. A 48-month car loan can be had at present 3.06 percent.[9] Under these terms, payments on a $20,000 car loan would amount to $443 per month. At 13.06 percent, payments would jump to $537. That amounts to $4,509 in extra payments just toward interest – and more than a quarter of the car’s loan value. This would also affect college finance, and all other forms of credit.

Lastly, the evidence indicates that, in general, high debt is correlated with slower economic growth. There has been a vigorous debate in the economics literature on this finding, its magnitude, and whether it represents a causal relationship. However, there is a clear understanding that debt absorbs private savings, and eventually saps the economy of need capital investment. In the midst of slow growth, any rapid fiscal consolidation would especially harm short-run economic growth. For example, CBO estimated that the “fiscal cliff” at the end of 2012 would have imposed a 3.9 percent growth penalty on the U.S. economy.[10] Such rapid policy change would ultimately reinforce certain negative budgetary pressures.

The growing risk that the United States could face such a fiscal crisis requires the serious consideration of a fiscal rule, namely a balanced budget amendment, to forestall the deleterious economic consequences that attend to sovereign debt crises.

The Value of Fiscal Rules

At present, the federal government does not have a fiscal “policy.” Instead, it has fiscal “outcomes”. The House and Senate do not always agree on a budget resolution. Annual appropriations reflect the contemporaneous politics of conference committee compromise, and White House negotiation. Often, the annual appropriations process is, in whole or in part, replaced with a continuing resolution. Annual discretionary spending is not coordinated in any way with the outlays from mandatory spending programs operating on autopilot. And nothing annually constrains overall spending to have any relationship to the fees and tax receipts flowing into the U.S. Treasury. The fiscal outcome is whatever it turns out to be – usually bad – and certainly not a policy choice.

I believe that it would be tremendously valuable for the federal government to adopt a fiscal rule. Such a rule could take the form of an overall cap on federal spending (perhaps as a share of GDP), a limit on the ratio of federal debt in the hands of the public relative to GDP, a balanced budget requirement, or many others. Committing to a fiscal rule would force the current, disjointed appropriations, mandatory spending, and tax decisions to fit coherently within the adopted fiscal rule. Accordingly, it would force lawmakers to make tough tradeoffs, especially across categories of spending.

Most importantly, it would give Congress a way to say “no.” Spending proposals would not simply have to be good ideas. They would have to be good enough to merit cutting other spending programs or using taxes to dragoon resources from the private sector. Congress would more easily be able to say, “not good enough, sorry.”

What should one look for in picking a fiscal rule? First, it should work; that is, it should help solve the problem of a threatening debt. A fiscal rule like PAYGO at best stops further deterioration of the fiscal outlook and does not help to solve the problem.

Second, it is important that there be a direct link between policymaker actions and the fiscal rule outcome.

Finally, the fiscal rule should be transparent so that the public and policymakers alike have a clear understanding of how it works. This is a strike against a rule like the ratio of debt-to-GDP. The public may not fully grasp the concept of federal debt in the hands of the public, and understandably does not understand how GDP is produced and measured. Without transparency and understanding, public support for the fiscal rule will be too weak for it to survive.

As documented by the Pew-Peterson Commission on Budget Reform other countries have benefitted from adopting fiscal rules.[11] The Dutch government established separate caps on expenditures for health care, social security and the labor market. There are also sub-caps within the core sectors.

Sweden reacted to a recession and fiscal crisis by adopting an expenditure ceiling and a target for the overall government surplus (averaged over the business cycle). Later (in 2000) a balanced budget requirement was introduced for local governments. Finally, in 2003 the public supported a constitutional amendment to limit annual federal government spending to avoid perennial deficits.

A lesson is that, no matter which rule is adopted, it will rise or fall based on political will to use it and the public’s support for its consequences.

A Balanced Budget Amendment

How should one think of proposals to amend the Constitution of the United States to require a balanced federal budget? It would clearly be quite significant. Despite the good intentions of the Budget Control Act of 2011, there is little indication that the resultant savings will do anything but delay the fiscal threats outlined above. Absent significant fiscal reform, these challenges will continue to evolve from pressing to irreversible. The distinguishing characteristics of a Constitutional amendment to address these challenges make it a far more robust tool in this endeavor.

First, fiscal constraints, in the form of spending caps, triggers, and other like devices are laudable, but fall short of Constitutional amendment in their efficacy as a fiscal rule similar to those pursued by nations such as the Netherlands and Sweden. A Constitutional amendment, by design, is (effectively) permanent, and therefore persistent, even if bypassed in certain exigent circumstances, in its effect on U.S. fiscal policy. Fiscal rules should allow policy figures to say “no.” A Constitutional amendment will not only allow that, but, given the gravity inherent in a Constitutional amendment, hopefully dissuade contemplation of any legislative end around that other rule might invite.

Second, there is a clear link between Congressional actions – cutting spending, raising taxes – and the adherence to a balanced budget amendment. Of course, Congressional action is not all that determines annual expenditures and receipts.

Military conflicts and other such contingencies can incur costs without advance Congressional action, while economic conditions can affect spending, such as with unemployment insurance and other assistance programs, and tax revenues. However, these fluctuations are ultimately not the driving force behind the U.S. fiscal imbalance. Indeed, in a world with stable tax revenue and without the need for military contingencies, the U S. would still be headed towards fiscal crisis. Rather, enacted spending and tax policy largely set forth the U S. fiscal path that must be altered to avert a fiscal crisis. A meaningful constraint on these factors would confront policymakers with the necessity to alter those polices, and as discussed above, to make the choices and tradeoffs needed to shore up the nation’s finances. Tying those choices to an immutable standard, in the form of a Constitutional amendment, would facilitate that process.

The ratification process is a third facet of a Constitutional amendment that augurs well for its efficacy. This is a process that takes years. Successful ratification of a Constitutional amendment requires acceptance at many levels of public engagement. For the purpose of constraining federal finances, this is beneficial, as it necessarily requires public “buy-in.” Without question, the changes needed to address federal spending policy will be difficult. Any process that engages the public, and by necessity, requires public complicity to be successful will ease the process of enacting otherwise difficult fiscal changes.

Lastly, the very nature of a Constitutional amendment shields it from the annual, or perhaps more frequent, vicissitudes of federal policymaking. It cannot be revised, modified, or otherwise ignored in the fashion of the many checks on fiscal policy enacted or attributable to the Congressional Budget Act of 1974 or its successors.

Congress cannot renege on its obligations with such an amendment in place. While unquestionably a constraint on Congress, as a parameter of federal policymaking it would be one by which all must abide.

Auxiliary Features of a Balanced Budget Proposal

As noted above, a balanced budget amendment to the Constitution has several unique characteristics that distinguish it as an effective fiscal rule. However, not all balanced budget amendments are created equal. Balanced budget amendments can differ significantly, with considerable variation in the consequence of their design.

While largely the result of choices by policymakers, the U.S. fiscal situation is, and will be in the future, shaped in some way by forces outside of the legislative process, such as war, calamity, of economic distress. Critical to an effective balanced budget amendment is the acknowledgment of this reality with a mechanism for adjusting to these forces without undermining the goal of the amendment to constrain fiscal policy. The abuse of emergency designations in legislation to get around budget enforcement is an example of what can happen when the goal of constraining fiscal policy is subordinated to flexibility in the face of some crisis, real or otherwise. Stringent accountability, such as the requirement of supermajority, affirmative votes can mitigate this problem.

Past iterations of balanced budget amendments have legitimately raised questions as to their capacity to limit the scale of the federal government. There is nothing inherent in a balanced budget amendment to limit federal spending beyond the belief that at some point, the tax burden necessary to balance the expenditure of a large federal government ultimately reaches an intolerable level. But there is nothing about a balanced budget amendment alone that precludes reaching tax and spending levels just approaching that tipping point, which is far from desirable policy. Accordingly, recent examples of balanced budget amendments seek to staunch the accumulation of debt, which is ensured by balance, while also limiting the spending to the historical revenue norm. Likewise, recent examples of balanced budget amendments that limit the Congress’s ability to raise taxes. In each case these limitations can be waived by supermajority votes. These are sound approaches that address concerns that a requirement to be in balance will add tax policy to the share of fiscal policy already on autopilot.

The last issue of concern, but with a less obvious remedy relates to enforcement. It is not obvious in any of the extant amendments what would occur if the requirements of the amendment were violated. The enforcement mechanism for these requirements arguably may not exist, and may not exist until tested after the ratification of a balanced budget amendment. While many criticisms of past approaches to balanced budget amendments have been meaningfully addressed in recent efforts, the question of enforcement remains a challenge that should be thoughtfully considered.

Thank you for the opportunity to appear today. I look forward to answering any

questions the Committee may have.

[1] Congressional Budget Office. 2017. The Long-Term Budget Outlook. Pub. No. 52480. https://www.cbo.gov/publication/52480

[2]Congressional Budget Office. 2017. An Update to The Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027. Pub. No. 52801. https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52801-june2017outlook.pdf

[3] The forgoing discussion is based on previous testimony to the House Financial Services Committee: https://financialservices.house.gov/uploadedfiles/hhrg-113-ba00-wstate-dholtzeakin-20140325.pdf

[4] http://www.taxpolicycenter.org/model-estimates/baseline-distribution-income-and-federal-taxes-march-2017/t17-0015-baseline

[5] https://www.cbo.gov/budget-options/2016/52247

[6]See: http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/pmms_archives.html; http://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/h15/data.htm

[7] http://www.freddiemac.com/pmms/

[8] https://www.dallasfed.org/educate/calculators/closed-calc.aspx

[9] http://markets.wsj.com/?mod=Home_MDW_MDC

[10] http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/cbofiles/attachments/FiscalRestraint_0.pdf