Testimony

July 30, 2020

Reducing Uncertainty and Restoring Confidence during the Coronavirus Recession

Joint Economic Committee

*The views expressed here are my own and do not represent the position of the American Action Forum. I am indebted to my colleague Gordon Gray for many valuable conversations.

Chairman Lee, Vice Chairman Beyer, and Members of the Subcommittee, thank you for the privilege of participating in this hearing on addressing the nation’s economic crisis. In this short testimony, I want to make four main points:

- The economy and, especially, the labor market entered 2020 in good condition, but have been buffeted by an economic downdraft of unprecedented scale and unique origins;

- The policy response thus far by the Federal Reserve and Congress has been correspondingly of unprecedented scale and has prevented an enormous amount of distress and economic damage;

- Examining the data from the onset of the recession highlights the importance of supply conditions and policies that assist businesses and their customers to operate in the presence of the virus; and

- There does not appear to be a strong case for “automatic stabilizers” in the form of expanded mandatory spending

Let me discuss these in turn.

COVID-19 and the Economy

The macroeconomic impact of the COVID-19 pandemic far exceeds any experience in our lifetimes. Essentially all the major leading economic indicators have seen historic declines, wiping out the hard-won gains from the longest recovery in U.S. history.

Recent Economic Trends

Prior to the pandemic, there had been a meaningful improvement in the persistence of healthy economic growth over the past three years. Gross domestic product (GDP) growth, measured as the growth from the same quarter in the previous year, accelerated steadily from a low of 1.3 percent in the 2nd quarter of 2016 to a recent peak of 3.2 percent in the 2nd quarter of 2018. Of note, throughout this period, GDP growth remained above the 1.8 percent growth rate that prevailed throughout the balance of the recovery.

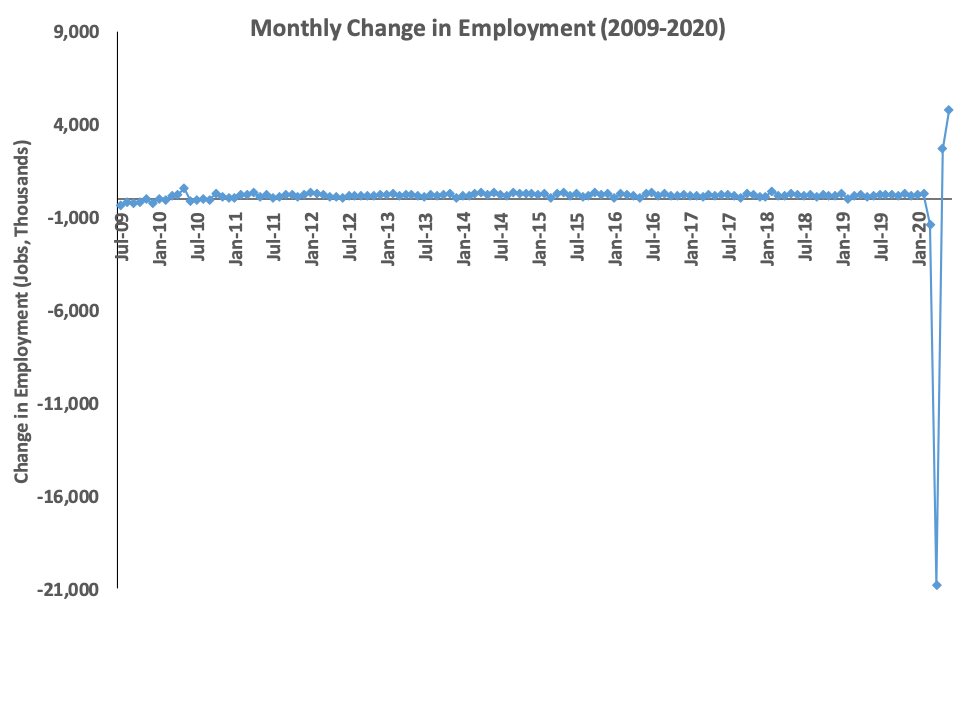

In June of 2009, the United States began the economic recovery from the Great Recession. What followed was nearly 11 years – the longest expansion in U.S. history – of steady if modest economic growth. Over that period, nearly 22 million jobs were created. Remarkably, the pace of job creation accelerated over the course of the recovery. Over the first half of the recovery, monthly job creation averaged 138,000; this number increased to 198,000 new jobs created per month over the latter half of the recovery.

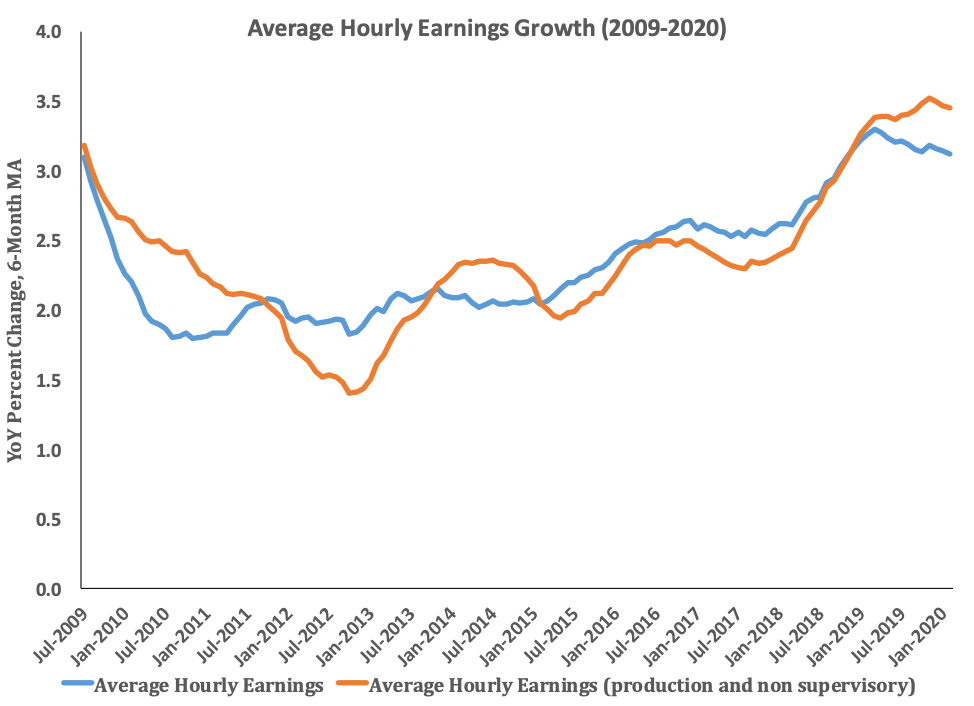

With higher growth and tighter labor markets, unemployment continued to fall as payroll and wage growth have accelerated. Wage growth has improved overall, including for non-supervisory workers. Indeed, from December 2018 onward, growth in hourly earnings (on a yearly moving average) for production and nonsupervisory workers outpaced that of workers overall every month.

The economic story of the recent past is the realization of years of modest growth finally beginning to accrue to individuals and families, broadly raising the standard of living. Recent accelerations in that growth punctuated a return to prosperity. That all came apart in March of 2020.

The Economic Impact of COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic precipitated a historic shuttering of the economy in March, guaranteeing that the broadest measure of economic wellbeing – real quarterly GDP growth – would reflect some of the devastation in the 1st quarter. Indeed, the Bureau of Economic Analysis’s (BEA) estimate for the decline in 1st quarter GDP is 5.0 percent on an annualized basis. This is the single largest drop in real GDP since 2008. While any contraction, particularly one on the order of magnitude with those observed during the Great Recession, is troubling, in this instance the contraction reflected only the leading edge of the economic devastation.

Higher frequency data reveal a historically devasted economy. Payrolls in April fell by 20.8 million, with private sector payrolls shedding 19.8 million jobs. The service sector lost over 18.3 million jobs. The leisure and hospitality industries were particularly devastated, losing over 7.5 million jobs. Goods-producing industries saw a decline of over 2.3 million. Government shed 952,000 jobs. No industry saw net positive hiring. To be sure, the last two months have seen a return to positive job growth, with 7.5 million jobs added to American payrolls.

The unemployment rate jumped to 14.7 percent in April, which exceeds the highest level since the Great Depression. As the Bureau of Labor Statistics notes, were it not for the classification of some workers as employed but “Absent for other reasons,” this number would be on the order of 5 percentage points higher. With the positive job growth in May and June, the unemployment rate has come down somewhat, though at 11.1 it remains more than a percentage point above the levels of unemployment seen during the Great Recession.

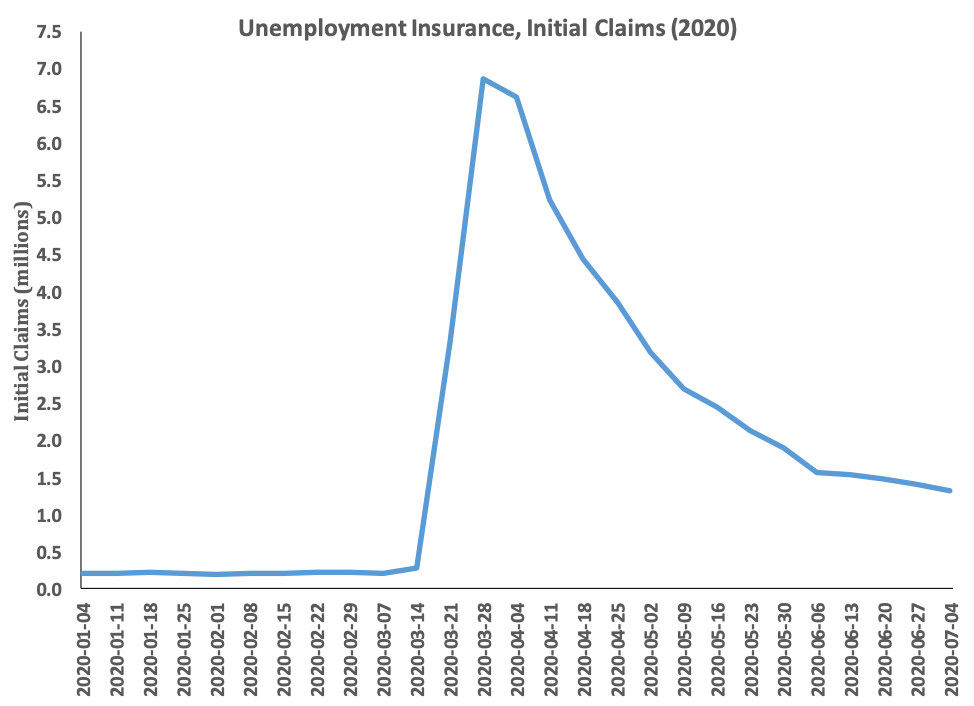

More frequent data still – weekly unemployment insurance (UI) claims – tell a similar story. Before March of this year, the single highest weekly initial claims report was 695,000 in 1982. No week in recorded U.S. history saw millions of Americans claiming unemployment insurance benefits. In the present environment, new UI claimants can only be measured in the millions.

The upshot of the most deliberate and comprehensive down to the most noisy and imperfect indicators is economic devastation of a singularly historic nature, and though a recovery is underway, it will not return the U.S. economy to “normal” for some time.

The Outlook

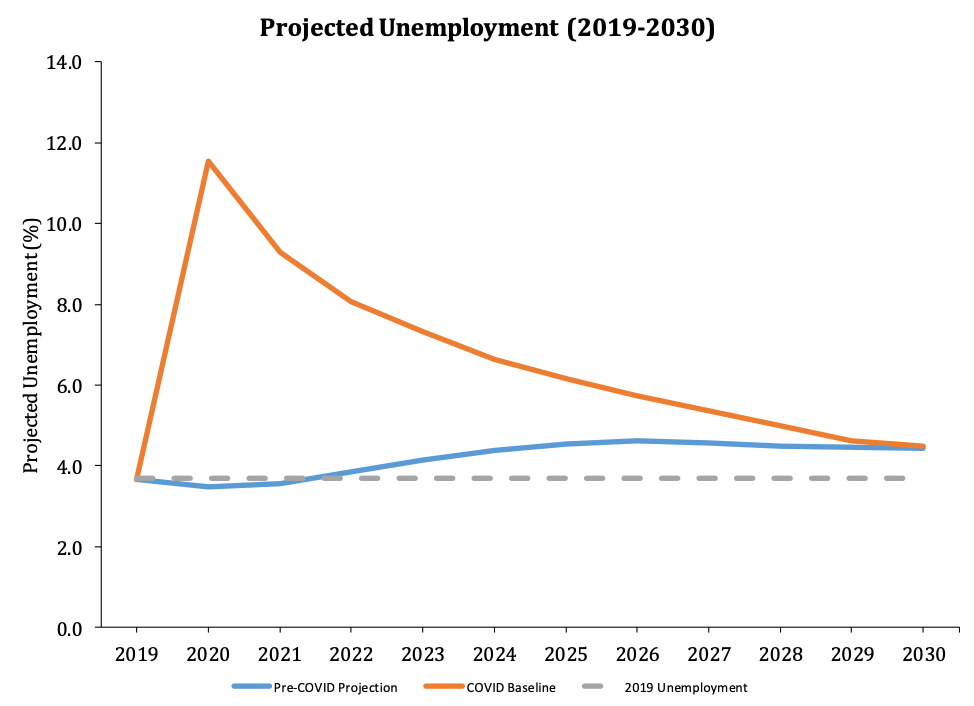

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) typically updates its economic forecast twice yearly – once in January and once in August. Before the pandemic, CBO’s baseline was keyed off of an economic forecast entirely abstracted from the effects of the pandemic, built on an assumption of real GDP growth in 2020 of 2.2 percent, an unemployment rate of 3.5 percent, and slowly rising interest rates. This was a mainstream forecast for the year, but to perform accurate cost-estimating during congressional consideration of the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, CBO had to essentially update its forecast on the fly, and it is to its credit that it did so. CBO has since completed a complete 10-year forecast.

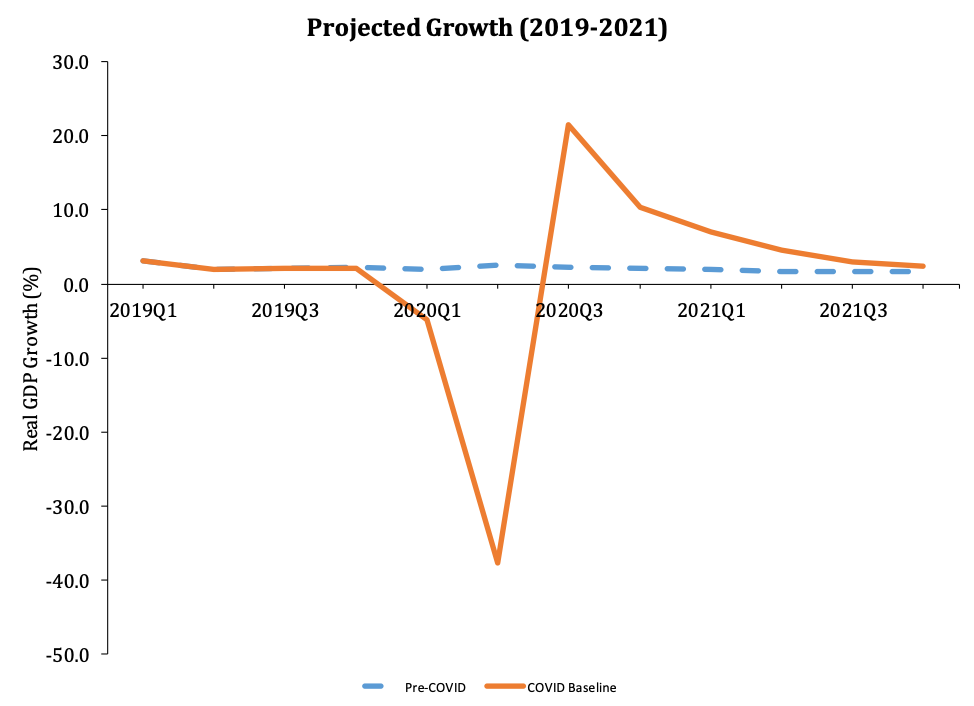

The new forecast reflects a similar outlook to other major post-COVID analyses – a sharp uptick in economic activity in the third quarter of 2020 that only partially restores the economic gains of the past several years. GDP is expected to fall 10 percent in the 2nd quarter, or 35 percent at an annual rate. (For perspective, in 1932, the worst year of the Great Depression, GDP fell 12 percent.)

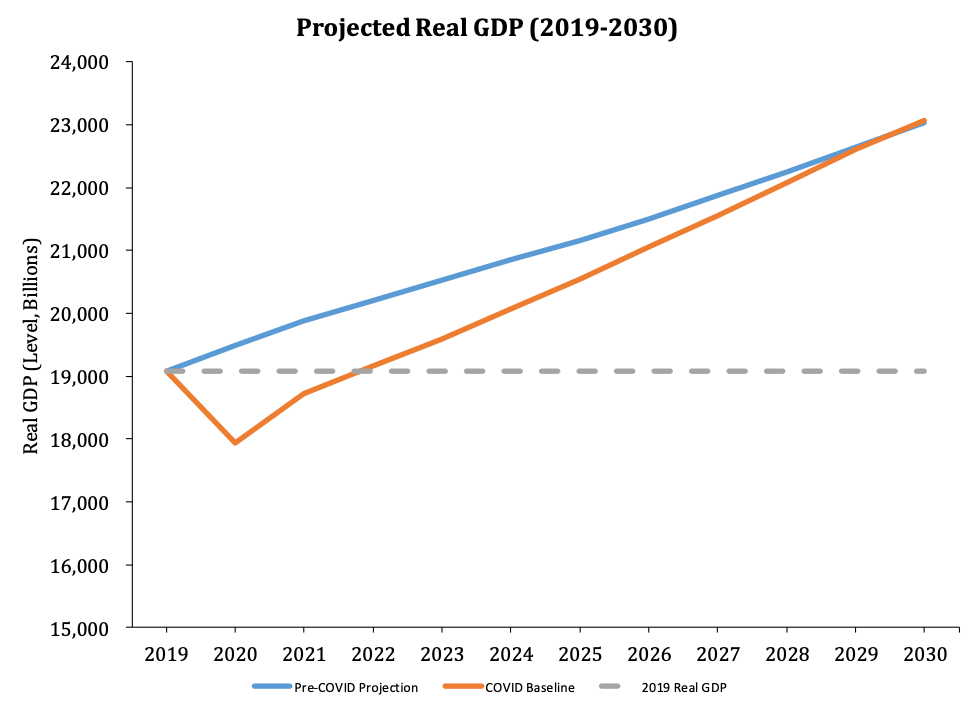

For the entire year 2020, GDP will be down 5.1 percent as every component of spending is expected to decline except federal government purchases. By contrast, in 2021 every component should be positive. The CBO sees growth at a rate of 4.0 percent in 2021. What this means is that despite a sharp, expected return to growth in Q3 of 2020, the scale of the prior contraction is such that CBO does not forecast the level of real GDP returning to pre-crisis levels until 2023.

By 2028, CBO projects unemployment will trend down to 4.5 percent, at which point CBO’s pre- and post-COVID forecasts converge. As noted, however, CBO does not estimate that unemployment will return to pre-COVID levels.

The implications of the current and projected losses associated with the COVID pandemic are highly consequential for federal policy. The CARES Act stands as the single largest fiscal intervention in U.S. history, an appropriate response to an historic challenge. Continual monitoring of the economic indicators – weekly, monthly, quarterly, annually – will continue to inform Congress on the direction and tenor of the recovery, and policymakers should tailor policies accordingly.

Next Steps for Fiscal Policy

The policy strategy thus far has been to use large amounts of Federal Reserve liquidity provision and taxpayer dollars to insulate to the degree possible the household and business sectors from the effects of extreme social distancing and quarantine. As successful as this approach has been, it has come at considerable economic cost and appears unsustainable.

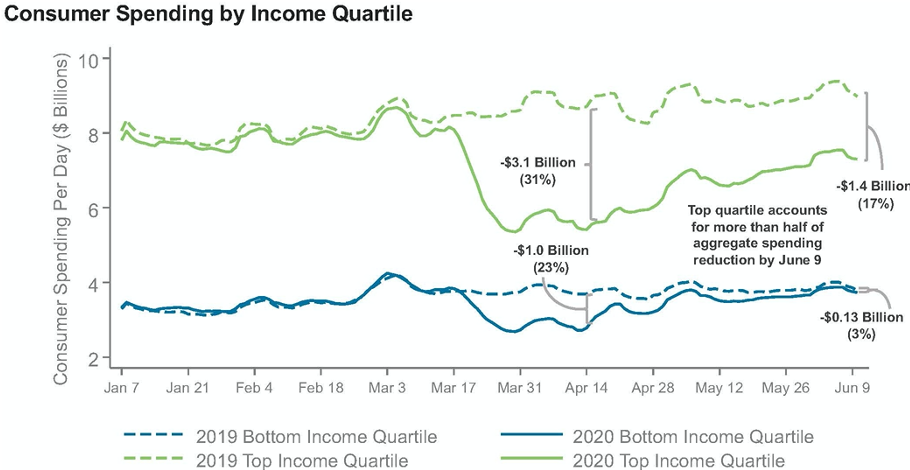

Going forward, it will be necessary to find a better way to operate the economy in the presence of the virus. In light of this, it is useful to review two charts from Chetty, et. al. The first, below, shows real-time data on consumer spending by quartile and carries three major lessons. First, the onset of the recession was driven by a sharp drop in spending, even though there had not been any decline in income.

This is a very different mechanism than was common in 20th century business cycles (which were income-driven) and 21st century business cycles (which thus far have been driven by financial bubbles).

The second lesson is that the sharp pullback in spending was largely due to high- income households. As the chart shows, spending in the top quartile fell much more sharply (31 percent compared to a year earlier) in late March than in the bottom quartile (23 percent). The COVID-19 recession emanated from more affluent Americans; responding to it should reflect this fact.

The final lesson is that federal transfers – checks to individuals and children, pandemic unemployment insurance – shored up the finances of lower-income consumers to such a degree that by early June their spending was down by only 3 percent compared to 2019. (Indeed, overall household sector finances were sufficiently fortified that the saving rate was 33 percent in April and 23 percent in May, putting roughly $2 trillion more in household checking and savings accounts compared to February.) But the spending by higher-income households remains depressed.

Why? Unlike the previous recession, the big cutbacks were not in big-ticket durable items or other non-durable goods. Instead, the diminished purchases of services was responsible for two-thirds of the decline. People stopped flying (transportation services), staying at hotels (housing services), attending concerts and movies (entertainment services), and so forth. Indeed, a stunning 2 percentage points of the 5 percentage point decline in GDP in the first quarter was due to reduced use of health care services.

The issue was the fear of individuals to participate in anything that involved personal contact. This fear produced the downturn, which was exacerbated by the lockdowns that occurred later.

A slightly more detailed examination of the data reveals that spending fell primarily among high-income households for in-person services (e.g. restaurants) and that these services were produced by low-income workers in small business in these high-income areas.

Traditional “stimulus” targeted at lower-income households will permit those households to spend more, but it will not restore the jobs of those workers in the affected small businesses because of the ongoing health concerns. Government- ordered re-openings will have little impact on local employment, because people will still avoid those same businesses.

Thus, the speed and scale of economic recovery will be proportional to the speed and scale of modifying workplaces to operate safely in the presence of the virus. Without that, workers will be reluctant to return to, and customers will continue to avoid, previously perfectly viable businesses. To the extent that public policy can play a supportive role in the economy, this problem strikes me as a perfect place for action.

One could easily design, for example, a tax credit equal to a fraction of the cost of protecting employees and reconfiguring workplaces. The former would consist of employee COVID-19 testing, deep cleaning and disinfectants, and personal protection equipment for employees. The latter would include expenses for reconfiguring places regularly used by customers or employees to bring them up to standards. The spending would have to occur in calendar year 2020 (and after the declaration of an emergency on March 13).

Since many firms will have no income tax liability in 2020, it makes sense for this policy to be a credit against payroll taxes and refundable. Since most employers remit their payroll taxes frequently, this could be implemented by simply reducing the amount of payroll taxes sent in, which would give the firms much-needed cash flow to do the renovations. Finally, one could put a limit on the total amount of the credit, either in absolute terms or per employee.

This is one example of focusing on the supply-side of the economy and using policy to offset an expensive shock imposed by the pandemic. A second supply-side focus should be continued assistance to small businesses – either existing survivors or new entrants replacing those that have folded – who will be the key employers as the economy seeks to regain full employment.

The final example is the future of the $600 per week federal supplement to state unemployment insurance benefits. This supplement made perfect sense when the objective was to make sure people quarantined and did not spread the coronavirus by going to work. In short, the $600 was designed to be lucrative enough to be better than working.

That is now a real problem as the policy objective shifts to encouraging more economic activity. More important, it is not a small problem. Research by the America Action Forum’s Isabel Soto indicates that up to 63 percent of the nation’s workers would make more on the maximum unemployment benefit than their pay at the previous job. Moreover, the fraction differs by state and could be as high as 75 percent. The bonus speaks highly of the taxpayers’ generosity, but it flunks any test of economic logic.

This problem extends beyond the private sector. The latest from Soto indicates that “At least 62 percent of all state and local [government] workers could make more on the enhanced unemployment benefit of $600 a week than at work.” In short,

Congress could fill the coffers of states and localities, jobs would still exist at full pay, and nearly two-thirds of workers would be financially better off on unemployment insurance.

To summarize, the strategy of using trillions of dollars to keep the economy in suspended animation and outwait the coronavirus is over. A traditional playbook of Keynesian stimulus – checks to low-income households and grants to states and localities – does not match the dynamics of the economic downturn. Instead, we need an aggressive strategy that is targeted at the problems facing the economy.

Automatic Stabilizers

Automatic stabilizers are provisions in law that generate greater aggregate demand as the economy slows or declines. For example, a progressive tax system acts as an automatic stabilizer because as incomes fall households move into lower tax brackets and have a greater fraction of their earnings available to spend. Similarly, the UI system serves as an automatic stabilizer by providing income to the unemployed.

Obviously, the United States already has in place automatic stabilizers. There has been interest, evidenced by this hearing, in augmenting the system of automatic stabilizers. For example, in a recent Wall Street Journal opinion piece, former Council of Economic Advisers Chairman Jason Furman argued, “Congress should pass a law immediately that would automatically trigger stimulus if the labor market deteriorates, with unemployment rising rapidly. The package should include not only tax cuts but also relief for states, as well as extra help for people most hurt by recessions. The legislation should be permanent, the measures lasting as long as needed in the next downturn and set to trigger in future ones as well.”

At an abstract level, the argument is appealing. But I have reservations about the idea at this juncture. First, the United States already has automatic stabilizers (as noted above) and there has been no compelling case made that they are somehow insufficient. Indeed, “how big” is a difficult question to answer. It is far from obvious (to me at least) how to appropriately scale the kinds of provisions that are suggested.

The alternative to automatic stabilizers is discretionary actions by Congress in the event of a downturn. Congress can (and has) cut taxes, enhanced unemployment insurance, provided assistance to states, augmented the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), and so on.

Thinking about the alternatives raises two additional concerns. First, from a budgetary perspective, automatic stabilizers are mandatory spending, while discretionary policy is (literally) discretionary spending. Other things being equal, it would be unwise to create additional mandatory spending programs – mandatory spending is the long-run budget problem.

The second additional concern is that it seems most likely that the outcome will be both automatic and discretionary responses. I consider it extremely unlikely that faced with a significant downturn, Congress and the administration will choose to do nothing and explain to the American people that their predecessors had taken care of this problem. Instead, regardless of the robustness of the automatic stabilizers that are in place, Congress and the administration will enact further discretionary policies. The result will be budgetary excess and unsound fiscal policy.

Thank you and I look forward to your questions.