Testimony

March 31, 2022

Testimony on: Affordability and Accessibility: Addressing the Housing Needs of America’s Seniors

United States Senate, Committee on Banking, Housing, and Urban Affairs

* The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum. I thank Douglas Holtz-Eakin for his assistance.

Chairman Brown, Ranking Member Toomey, and members of the committee, thank you for the privilege of appearing today to discuss the housing needs of America’s seniors and of the country more generally. My testimony will focus on three main points:

- Increased government intervention in the housing market has in most cases done more harm than good. Congressional subsidies and agency policies have a patchy record of success at best, and homeownership rates remain roughly the same as they did in the 1970s. Further congressional action will continue to artificially constrain the free market, reducing the ability of private actors to compete. This lowers the quality of services, reduces availability, and increases the prices of available homes, all while increasing the systemic risk present in the housing ecosystem at a time of significant market stress.

- No specific policies for addressing the housing needs of seniors can offset the negative impact of a poor macroeconomic environment. Due to prior policy errors, the United States is facing inflation levels previously unseen in a generation, which harms seniors and vulnerable populations most. Congress would be better placed to form a more complete understanding of the current state of existing subsidies, both of existing Housing and Urban Development initiatives and COVID-19 grants, from which a significant amount of funding remains unspent.

- Further demand-side subsidies fail to account for – and instead exacerbate – the two primary underlying causes of stress in the housing market: a lack of supply and the role played by the government-sponsored enterprises (GSEs) Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac. If Congress must intervene in the functioning of the free market to meet specific policy goals, it must do so on the supply side, for example by changing local zoning regulations and continuing the efforts to end the conservatorship of the GSEs. By contrast, demand subsidies increase demand, which results in a rise in house prices, making housing unaffordable to those who need it most. Congress may achieve precisely the opposite of what it sets out to do.

I will discuss these in turn.

Government Intervention in Housing Has Frequently Done More Harm Than Good

Housing finance was at the center of the 2008 financial crisis that visited substantial economic stress on Americans and spawned dramatic government intervention. Yet more than a decade later, the central actors in the crisis and response – Fannie Mae, Freddie Mac, and the Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) – remain essentially unchanged.

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac need to be wound down and closed as a matter of both policy and politics. From a policy perspective, the GSEs were central elements of the 2008 crisis. First, they were part of the securitization process that lowered mortgage credit quality standards. Second, as large financial institutions whose failures risked contagion, they were massive and multidimensional cases of the too-big-to-fail problem. Policymakers were unwilling to let them fail because financial institutions around the world bore significant counterparty risk to them through holdings of GSE debt, certain funding markets depended on the value of their debt, and ongoing mortgage market operation depended on their continued existence. They were by far the most expensive institutional failures to the taxpayer and are an ongoing cost.

At a more targeted level, it is easy to find examples of government intervention and overreach that have had negative impacts on the housing market. Federal Reserve policies, from low interest rates to significant mortgage-backed security purchases[1] have contributed to high housing prices. The Federal Housing Agency has significantly expanded its role and, with the GSEs, guarantees over $7 trillion in mortgage-related debt to the borrowers least able to repay[2]. The Department of Treasury has declined to end the Qualified Mortgage (QM) Patch that allows the GSEs to breach safe lending standards set by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau. Senior homeowners, in particular, have struggled with the ineffective and inconsistent servicing of Home Equity Conversion Mortgages[3].

The federal government already provides multiple avenues of support for the construction of affordable housing and assistance for low-income renters and homebuyers, including seniors. While the success of these programs can be debated, support exists in many forms; primarily, the federal government provides appropriated funding through more than 30 programs within the Department of Housing and Urban Development, tax credits and deductions for both corporations and individuals, housing programs for veterans through the Department of Veterans’ Affairs, rural housing programs through the Department of Agriculture, and mortgage insurance programs through the Federal Housing Administration and government corporation Ginnie Mae.

The failures of this overly complex constellation of programs not performing as designed are clear. House price indices are at record highs, housing affordability indices are declining[4], and homeownership rates have barely changed since the 1970s[5]. The housing market is under considerable stress, further impacted by the challenges of the recent pandemic. It is difficult, however, to point to stressed markets as a justification for further government intervention if the government itself is responsible for significant portions of that stress – there is seemingly less evidence of market failure than there is of government failure.

Inflation and the Macroeconomic Environment

In many respects, the current state of the United States economy is quite good. Real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product (GDP) rose at an annual rate of 7.0 percent in the 4th quarter of 2021. The unemployment rate stood at 3.8 percent in the most recent (February) employment report. Wages are rising rapidly; average nominal (not adjusted for inflation) hourly earnings are up 5.1 percent from February 2021 – 6.7 percent for non-supervisory and production workers.

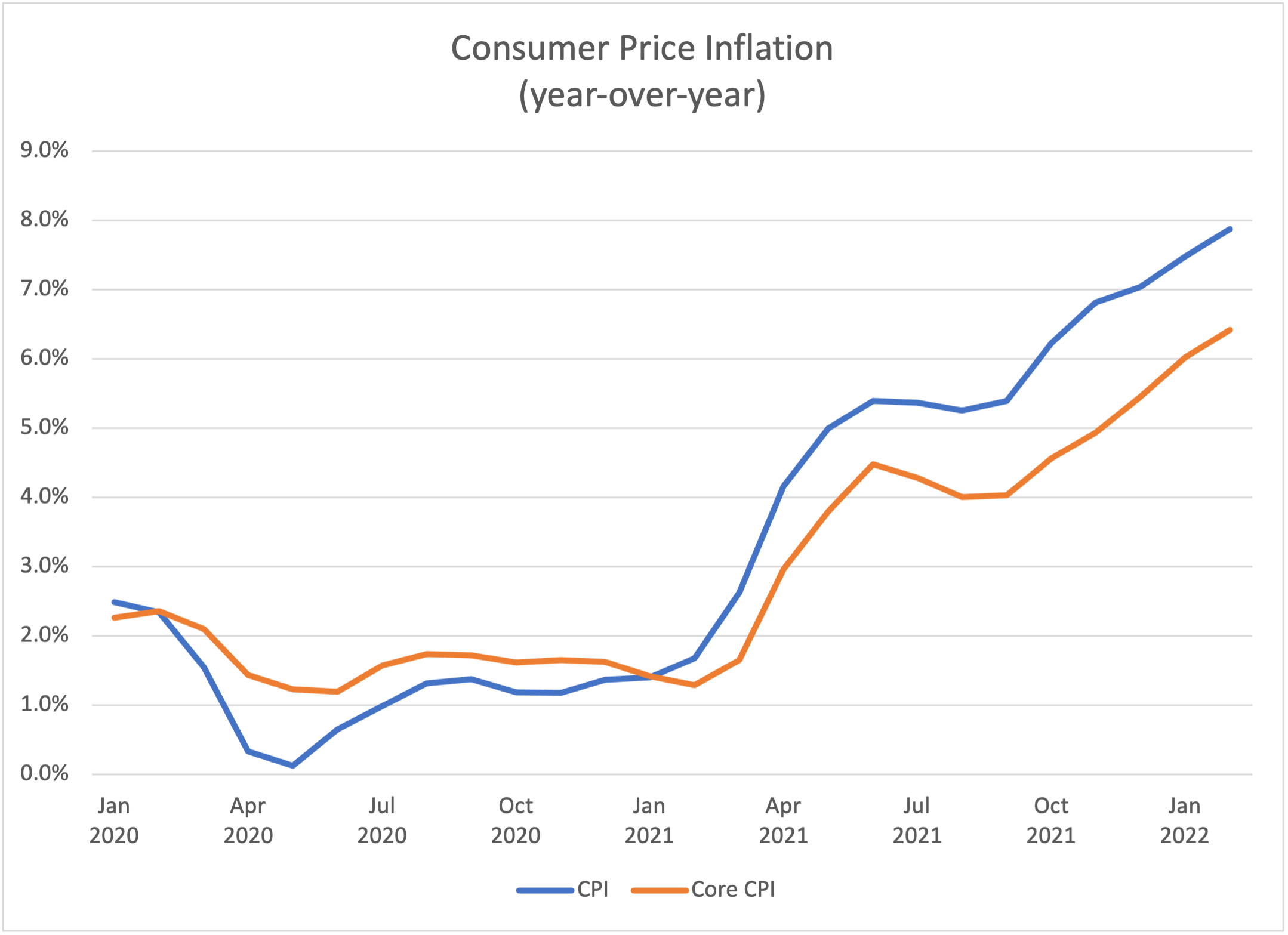

The Achilles heel of the outlook, however, is the worst inflation problem in 40 years. As measured by the Consumer Price Index (CPI), year-over-year inflation has risen from 1.4 percent in January 2021 to 7.9 percent in February 2022 (see chart, below). So-called “core” (non-food, non-energy) CPI is up from 1.4 to 6.4 percent over the same period. In each case, the measure is the highest since 1982.

Even these data, however, disguise the pain of inflation. Over one-half of the typical family budget is devoted to food, energy, and shelter and the composite inflation for these items is currently 8.4 percent. Energy costs are up a staggering 25.6 percent; gasoline alone is up 38.0 percent and regular gas is $4.24 a gallon, on average.[6]

These data raise the important question: How did the United States develop this inflation problem?

In contrast to the policy actions in 2020, the major action in 2021 – the American Rescue Plan (ARP) – was partisan in nature, untimely, and excessively large and poorly designed. It was simply a major policy error. As the economy entered 2021, it was growing strongly due to the continued support and the arrival of the vaccines as an additional weapon in the fight against the coronavirus. The $1.9 trillion ARP was advertised as much-needed stimulus to reverse the course of the economy and restore growth. The economy was no longer in recession, however, and was growing at a roughly 6.5 percent annual rate. There was simply no need for additional stimulus, especially as a large fraction of the household support in the CARES and appropriations acts had been saved and was available.

Even worse, the ARP was excessively large. Real GDP at the time was below its potential, with the output gap somewhere in the vicinity of $450 billion (in 2012 dollars). The $1.9 trillion stimulus was a bit over $1.6 trillion in 2012 dollars. Thus, the law was a stimulus of over three times the size of the output gap that needed to be closed to get the economy back to potential. Based on any reasonable economic theory of stimulus, $1.9 trillion is far too large, particularly given supply constraints. The ARP (passed in March) did not appreciably alter the pace of growth from the first to the second quarter, but it did fuel inflation.

The inflation of 2021 reflects a combination of these forces. The COVID-19 pandemic has wreaked havoc on labor markets worldwide, and the resulting disruptions in supply chains and goods production have been well-documented. These supply constraints increased costs and generated higher inflation across the globe. European consumer price inflation, for example, increased about one percentage point each quarter and ended 2021 at 4 percent. Part of the U.S. experience is driven by supply chain issues as well.

But the ARP added fuel to the fire. Inflation responded immediately to the policy error, jumping from 1.9 percent in the first quarter to 4.8 percent in the second quarter – nearly three times the increase in supply-driven inflation in Europe. The fiscal stimulus was reinforced by an aggressively accommodative monetary policy that featured zero interest rates and continuous, large monetary infusions. Inflation continued to rise as the year went on.

Inflation is a clear problem in the present. Will it continue? To be durable, price inflation must be accompanied by wage inflation and higher inflation expectations. Wage inflation has already arrived, as average hourly earnings rose 5.1 percent from February 2020 to February 2022. To compound matters, consumers’ expectations for inflation over the next year – as measured by the New York Federal Reserve Bank – rose from 3 percent to 6 percent during 2021. This raises the specter of workers bargaining for higher wages as a hedge against expected inflation. When those labor cost increases get passed on to consumers, the expected inflation becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy.

The Build Back Better agenda, which has taken various legislative incarnations thus far, is a massive expansion of the social safety net, an enormous and poorly designed tax increase, a climate change policy, an education policy, and much more.

At the macro level, it is of questionable merit as the way forward for pro-growth fiscal policy. American Action Forum research highlights one area of concern regarding the economic consequences of raising the proposed taxes and spending it exclusively on productive infrastructure. The economy shrinks instead of grows, as the negative effects of the taxes outweigh even a disciplined focus on productive spending. Since the actual Build Back Better Act (BBBA) is not a disciplined infrastructure spending program, the likely impacts would be even more negative.

The significant macroeconomic risks presented by further cash infusions are made more distressing by the substantial amounts of COVID-19 funding from previous congressional initiatives that remain unspent. As much as 89 percent of federal rental aid remained unspent in August of last year[7], causing the Department of Treasury to initiate major re-allocation efforts[8].

Housing Stresses Are Caused by Supply, Not Demand

Even if Congress could design legislation that does not duplicate existing efforts, works perfectly as intended, creates sensible market incentives and empowers private actors, while at the same time not putting overt pressure on inflation and the deficit, any legislative solution focusing on demand rather than supply will only exacerbate the problems facing seniors and all Americans. The two most significant stresses to the housing market are shortfalls in supply and the market-distorting role played by the GSEs.

Housing demand is especially high as a result of low mortgage rates and a coronavirus-inspired flight from large urban centers and into homes better suited to remote work[9]. Despite these high prices, the risks of an economic crash as a result of a collapse of the housing market appear low due to the low availability of mortgage credit and better underwriting standards. The rate of homeownership is on track to fall, however, and housing inequalities, felt disproportionately by seniors and other vulnerable populations, will be exacerbated. Demand-side subsidies, such as those found in the BBBA, will further exacerbate existing demand issues.

Housing supply is constrained by a dearth of new construction resulting from low labor availability, the high cost of materials, and restrictive local regulations. Existing homes are not returning to the market at typical rates as economic stresses, the low mortgage rate environment, and the unknowns of listing a home in the backdrop of a global pandemic caused homeowners to delay or cancel their plans to list. Housing inventory, while on track to rise, is at historic lows. The total inventory of homes available for sale fell 26 percent in January 2021 year-over-year[10]. At its lowest point, the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis estimated that there remained only three and a half months of total housing inventory – in other words, it would be only three and a half months without construction until there would be no homes available in the United States. Housing permits and starts remain at pre-pandemic levels[11]. Fundamentally, there must be homes for our seniors to move into, and demand-side subsidies will only increase the population of potential homeowners chasing the same, small number of available houses, further increasing prices.

The United States does not have a functioning private secondary mortgage market and has a wildly distorted primary market thanks to Fannie and Freddie. If Congress seeks a healthy and functioning housing market that benefits all participants, including seniors, then it must continue its efforts to reform the GSEs. Instead, this administration has reversed these gains, decreasing the amount of capital the GSEs are required to hold and once again allowing them to purchase the riskiest mortgages[12]. The degree to which government has replaced private actors in the housing space has stalled if not prevented innovation and competition from the free market, undermining the capitalist economy on which the United States is based and failing to serve all Americans, including seniors.

Thank you and I look forward to your questions.

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/tracker-the-federal-reserves-balance-sheet/

[2] https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/federal-government-has-dramatically-expanded-exposure-to-risky-mortgages/2019/10/02/d862ab40-ce79-11e9-87fa-8501a456c003_story.html

[3] https://www.nclc.org/images/pdf/foreclosure_mortgage/reverse-mortgages/ib-hecm-examples-loss-mitigation.pdf

[4] https://www.americanactionforum.org/chartbook/housing-chartbook-q4-2021/

[5] https://www.census.gov/housing/hvs/data/histtabs.html

[6] https://gasprices.aaa.com/

[7] https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2021/08/25/89-federal-rental-assistance-unspent-evictions-crisis-looms/5584441001/

[8] https://home.treasury.gov/policy-issues/coronavirus/assistance-for-state-local-and-tribal-governments/emergency-rental-assistance-program

[9] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/understanding-the-national-increase-in-house-prices/

[10] https://www.bankrate.com/real-estate/why-are-house-prices-going-up/

[11] https://www.americanactionforum.org/chartbook/housing-chartbook-q4-2021/

[12] https://www.americanactionforum.org/insight/fhfa-reverses-previous-housing-market-reform-progress/