Testimony

February 11, 2020

The Disappearing Corporate Income Tax

United States House of Representatives Committee on Ways and Means

Chairman Neal, Ranking Member Brady, and members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to discuss the corporation income tax and, in particular, the impact of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) on the taxation of U.S. businesses. I would like to make three points:

- The jumping off point for the TCJA was a bipartisan agreement that the U.S. corporation income tax needed fundamental reforms;

- The TCJA, while imperfect, addressed many of the most important elements that harmed the tax-competitiveness of U.S.-headquartered multinationals, and it improved the growth incentives overall; and

- While there are limited data available this soon after the passage of the TCJA, there has been a U-turn on the loss of corporate headquarters, a dramatic shift in repatriated funds, and promising shifts in top-line economic growth, business investment, and wage growth.

Let me discuss these in turn.

The Corporation Income Tax and Reform[2]

International Competitiveness and Headquarter Decisions[3]

Prior to the enactment of the TCJA, the U.S. corporate tax code remained largely unchanged for decades, with the last major rate reduction passed by Congress in 1986.[4] During the interim, competitor nations made significant changes to their business tax systems by reducing tax rates and moving away from the taxation of worldwide income. Relative to other major economies, the United States went from being roughly on par with major trading partners to imposing the highest statutory tax rate on corporation income. While less stark than the United States’ high statutory rate, the United States also imposed large effective rates. According to a study by PricewaterhouseCoopers, “companies headquartered in the United States faced an average effective tax rate of 27.7 percent compared to a rate of 19.5 percent for their foreign-headquartered counterparts. By country, U.S.-headquartered companies faced a higher worldwide effective tax rate than their counterparts headquartered in 53 of the 58 foreign countries.”[5]

The United States failed another competitiveness test in the design of its international tax system. The U.S. corporation income tax applied to the worldwide earnings of U.S.-headquartered firms. U.S. companies paid U.S. income taxes on income earned both domestically and abroad, although the United States allowed a foreign tax credit up to the U.S. tax liability for taxes paid to foreign governments. Active income earned in foreign countries was generally only subject to U.S. income tax once it was repatriated, giving an incentive for companies to reinvest earnings anywhere but in the United States. This system distorted the international behavior of U.S. firms and essentially trapped offshore foreign earnings that might otherwise be repatriated back to the United States.

While the United States maintained an international tax system that disadvantaged U.S. firms competing abroad, many U.S. trading partners shifted toward territorial systems that exempt, either entirely or to a large degree, foreign-source income. Of the 34 economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), for example, 29 have adopted systems with some form of exemption or deduction for dividend income.[6]

One manifestation of the competitive disadvantage faced by U.S. corporations was decisions on the location of headquarters. The issue of so-called “inversions” remained at the forefront of tax policy and politics. Originally, tax inversions involved a single company flipping the roles of U.S. headquarters and foreign subsidiary – i.e. “inverting.” Tax changes in the early 2000s largely ended this practice. Next, whenever a U.S. firm sought to acquire or merge with a foreign firm, the tax advantages of being subjected to a lower rate and a territorial base made it inevitable that the combined firm would be headquartered outside the United States. In these cases, inversions took place in the context of these otherwise strategic and valued business opportunities. Most recently, foreign firms have recognized that freeing U.S. companies of their tax disadvantage allows foreign acquirers to use the same capital, technologies, and workers more effectively. Inversions were occurring because foreign firms were acquiring U.S. firms.

A macroeconomic analysis of former House Ways and Means Chairman Dave Camp’s tax reform proposal is instructive on the incentives inherent in the old tax code for capital flight. John Diamond and George Zodrow examined how reform similar to that proposed by former Chairman Camp would affect capital flows compared to pre-TCJA law.[7] In the long-run, the authors estimated that a reform that lowered corporate rates and moved to an internationally competitive divided-exemption system would increase U.S. holdings of firm-specific capital by 23.5 percent, while the net change in domestic ordinary capital would be a 5 percent increase. It is important to note that these are relative measurements – they were relative to current law at the time. If the spate of announcements of inversions in the years leading up to the enactment of the TCJA is any indication, the old tax code was inducing capital flight. Accordingly, the 23.5 percent and 5 percent increases in firm-specific and ordinary stock, respectively, may be interpreted in part as the effect of precluding future tax inversions.

Placing a value on this potential equity flight is uncertain, but based on these estimates, roughly 15 percent, or $876 billion, of U.S.-based capital was estimated to be at risk of moving overseas under the old code.[8]

Finally, it is an important reminder that everyone bears the burden of the corporate tax. Corporations are not walled off from the broader economy, and neither are the taxes imposed on corporate income. Taxes on corporations fall on stockholders, employees, and consumers alike. The incidence of the corporate tax continues to be debated, but it is clear that the burden on labor must be acknowledged. A survey compiled by the president’s Council of Economic Advisers aptly summarizes the economics literature and finds that while differing greatly, empirical estimates have been trending upwards over time, reflecting the dynamism of global capital flows that characterize the modern economy.[9] One study by economists at the American Enterprise Institute, for example, concluded that for every 1 percent increase in corporate tax rates, wages decrease by 1 percent.[10]

Taxation of Pass-thru Entities

In 2016, over 150 million individual tax returns were filed, covering over $10.2 trillion in income.[11] These returns also include millions of businesses that do not file as C corporations. As of 2012, there were 31.1 million non-farm businesses filing tax returns: 23.6 million sole-proprietors, 4.2 million S corporations, and 3.4 million partnerships (including limited liability companies). These entities represent more than one-half of business income. For this reason, any reform of business taxation cannot be focused on the corporation income tax alone.

The need for reform was widely recognized. The House Ways and Means Committee had undertaken comprehensive reform efforts spanning several years, the Obama Administration proposed corporate reforms, and the Senate Finance Committee had bipartisan working groups intended to address these problems.

Important Economic Elements of the TCJA

The TCJA addressed some of the most glaring flaws in the business tax code. It lowered the corporation income tax rate to a more globally competitive level, enhanced incentives to investment in equipment, addressed some of the disparate tax treatment between debt and equity, and refashioned the nation’s international tax regime. Primarily for these reasons, the TCJA will enhance incentives for business investment in the United States.

At 21 percent, the federal corporate tax rate makes investments in the United States more competitive for both U.S. and foreign-headquartered companies operating in a global economy. As noted above, prior to the TCJA, the U.S. statutory and effective tax rates were among the highest in the developed world. In contrast, in 2020 the combined U.S. federal and state statutory corporate tax rate is just under 3 percentage points higher than the average of the other 35 OECD countries. It is important, however, to recall that after the 1986 reforms, the United States had the lowest tax rate only to be overtaken by other countries. Already we have seen foreign countries lower their corporate tax rates to re-establish a competitive advantage since Congress passed the TCJA.

Expensing – the immediate deduction of 100 percent of the cost of investment in qualifying equipment – is an important provision that should be made permanent and extended more broadly. Expensing lowers the cost of capital and provides strong incentives for business investment. It is also the route to a more neutral tax code. If all physical investment were to be expensed, the tax code would treat equally investments in human capital (training), intellectual capital, and physical capital. There is no good reason to have the tax code tilt the playing field when choosing how best to raise productivity in a firm.

Finally, the TCJA moved the United States toward a territorial system of taxation and refashioned the international tax rules. The combination of a territorial system and competitive tax rate has ended the “lock-out” effect of the previous tax code and eliminated the impetus for loss of headquarters. The foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) provision levels the playing field for U.S. businesses that invest domestically (rather than abroad) when the products and services are sold to foreign customers. The overall effect is a dramatic change in the net incentives to invest in the United States.

Revenue Outlook

TCJA reduced corporate income tax receipts; receipts in fiscal 2019 were $230 billion, down from $344 billion in 2015. This drop was to be expected. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO), however, projects receipts to steadily rise over the next decade and reach $406 billion in 2030. At the same time, corporate receipts will rise as a share of total receipts, reaching a peak of 8.5 percent, well above the 6.1 percent in 2018.

As part of the debate over the appropriate level of corporate taxation, it has become an unfortunate tradition in the corporate taxation debate to analyze the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) filings of public U.S. firms and pretend to do their taxes. The result is typical an outcry against U.S. firms that are not deemed to have paid their “fair share.” The problem is that this exercise is detached from tax reality.

The most important point to understand about any of these types of analyses is that financial reports, such as Forms 10K and 10Q, are not tax returns. Any analysis purporting to compute the taxable income of a U.S. firm is necessarily speculative.

Why does it matter that financial reports are not the same as tax returns? Financial reports adhere to Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP) as set forth by the Financial Accounting Standards Board . GAAP or “book” income departs substantially from tax returns. Firms’ financial statements are reported on an accrual basis, where tax returns are based on firm cash flows. Moreover, firms have some degree of flexibility in determining their own fiscal years – the Internal Revenue Service has a rather more rigid schedule for tax payments. These distinctions are principally about timing. Accrual accounting is based on present values, which includes a time value. Financial reports may not cover the same period of time as a tax return. This difference can animate substantial differences in firms’ tax obligations between those reported in financial statements and those filed with the SEC.

One of the largest differences in financial reporting and tax returns is in the treatment of investment. Under GAAP accounting, firms can only deduct or expense a portion of a given capital investment (unlike labor costs, which are fully deductible except for some limitations on executive compensation), but under federal tax law firms could deduct a greater share of their capital investments for tax purposes than was allowable under GAAP accounting. The tax incentive for investment has been a deliberate tax policy choice over many administrations and Congresses. Indeed, prior to the TCJA’s temporary full expensing provision, investment was fully deductible under the Obama Administration in 2011.

All else equal, for a firm making an investment, this means that reported profit will be higher under GAAP accounting than for tax purposes. Some critics exploit this distinction, suggesting firms that expense investment are engaging in tax “avoidance,” where they are simply following the law.

This distinction also reflects a logical flaw in some of the critiques of the TCJA – it is contradictory to bemoan the pace of investment under the TCJA, and then begrudge the investment that gives rise to the utilization of investment tax incentives.

Timing underpins another critical distinction between GAAP-derived tax estimates and real tax filings. The tax code allows companies to smooth out income by allowing losses to be carried forward (or backward) for a number of years. This provision makes practical sense for several reasons but lends itself to exploitation by critics. A firm may be profitable in a given year, but only after years of losses. After the Great Recession, this was common for many firms. A snapshot of the company in its single year of profitability is a necessarily distorted view, but one that some tax critics tend to highlight.

Implementation

It is important to recognize that passage of the TCJA is not equivalent to implementation. Global companies affected by the international provisions in the Base Erosion and Anti-Abuse Tax (BEAT), Global Intangible Lightly Tax Income (GILTI), and the Foreign-Derived Intangible Income (FDII) had to await final rulemaking by the Department of the Treasury.

Post-TCJA Performance

Recall that one of the most significant reforms in the TCJA was the movement from a worldwide system of taxation to a territorial system. In the former, U.S. firms were taxed on profits regardless of where on the globe they were earned – with the caveat that the final tax was not imposed until the money was brought back (repatriated) to the United States. As a result, many firms had elected to leave earnings overseas, and the pile of unrepatriated cash was growing rapidly.

Under the new system, only those profits earned in the United States (the “territory”) will be subject to the regular corporate income tax. Taken at face value, the switch from worldwide to territorial would permit those overseas stockpiles to escape tax entirely. To remedy this potential pitfall, the TCJA contained a one-time transition tax (15.5 percent for cash in liquid assets; 8 percent on other assets) on legacy overseas earnings, regardless of whether they are repatriated. That tax would be payable over the next 8 years.

This provision provides a quick test of the TCJA’s efficacy. Since firms owe the tax no matter what, they should only repatriate the legacy earnings if the United States has a become a better environment in which to invest – hence the interest in money being brought into the United States.

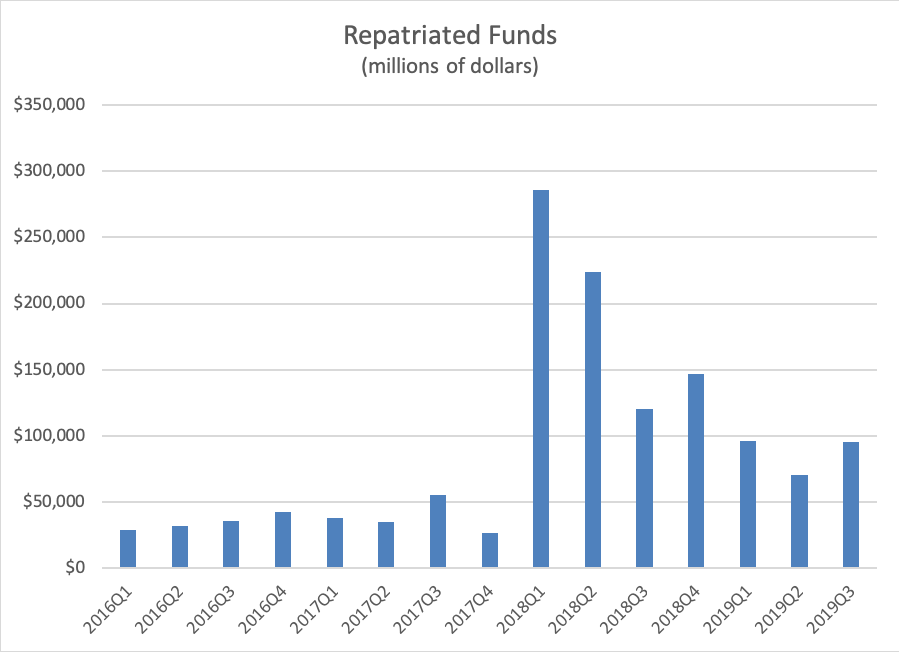

As shown in the chart below, there has been a surge of repatriated funds into the United States in the aftermath of the TCJA, and repatriations remain above their pre-reform norms. Based on data through the third quarter of 2019, U.S. companies are on pace to bring back $1.1 trillion of foreign earnings in the first two years after tax reform.

Is a trillion dollars of repatriation “large,” and does it indicate success for the TCJA? A recent Wall Street Journal story seemingly would suggest not.[12] “U.S. companies have moved cautiously in repatriating profits stockpiled overseas in response to last year’s tax-law rewrite, after the Trump Administration’s assertions that trillions of dollars would come home quickly and supercharge the domestic economy.” Unfortunately, this assessment is driven by a statement – “We expect to have in excess of $4 trillion brought back very shortly” – by President Trump in August. $4 trillion might reflect enthusiasm and aspiration, but it is well north of any other estimate of the potential repatriation sum. Indeed, most estimates clustered in the $1 to $1.5 trillion range, which is roughly the current pace. And this volume is well above historical norms – the volume of repatriated earnings in the first half of 2018 alone is more than in all of 2015, 2016, and 2017 combined – so the impact of the TCJA is fairly clear.

The success regarding inversions is even more striking. After years of having five to six prominent companies annually depart the United States, inversions have simply stopped. Multinationals are bringing operations back to the United States, and many acquisitions of U.S. businesses now are made by U.S. firms, rather than foreign buyers.

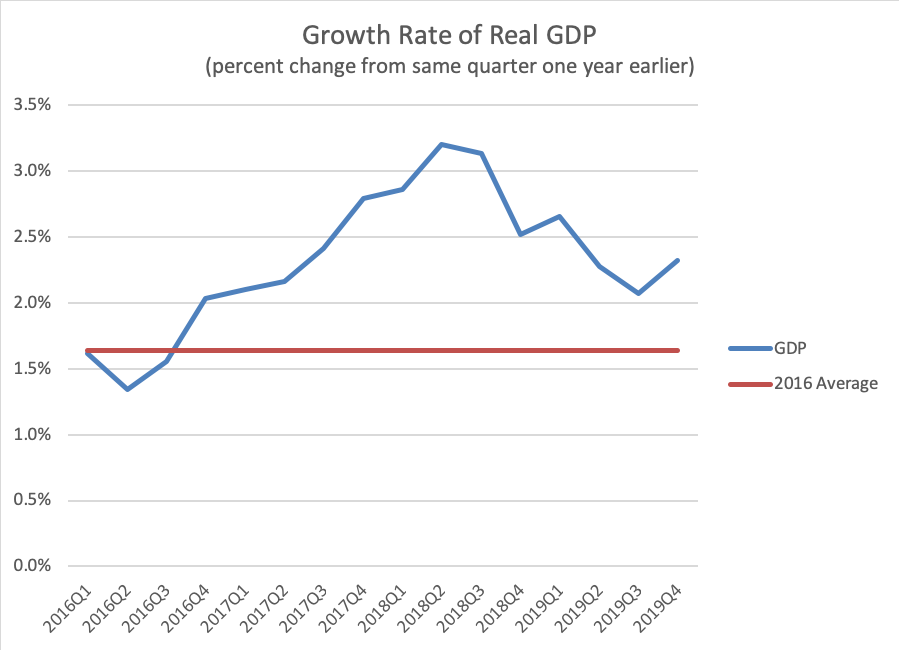

Of course, the bottom line is whether the plan has produced better growth. Certainly, the top-line rate of economic growth has improved.

Growth ramped up in the immediate aftermath of the TCJA. While it still remains above the 2016 level, the growth rate tailed off in 2019. This slowdown coincides with slower business investment (below) and, especially, the arrival of a full-blown trade war. As a point of comparison, year-over-year growth in real gross domestic product (GDP) in the G20 averaged 0.9 percent over this same period, with the most rapid growth being 1.1 percent.

Growth in business investment (nonresidential fixed investment, adjusted for inflation) reached a year-over-year peak of 6.9 percent in 2018. Despite the headwinds in 2019, cumulative business investment in 2018 and 2019 was $5.7 trillion.[13] Adjusting for inflation, total business investment hit record highs in both 2018 and 2019.[14] The growth in business investment since 2017 has greatly exceeded CBO’s June 2017 forecast, its last projection prior to TCJA.[15] In 2018, business investment grew by 6.4 percent compared to CBO’s 2017 forecast of 3.6 percent growth. The level of business investment in 2019 was 8.6 percent higher than in 2017, compared to CBO’s 2017 forecast of 5.9 percent.

On balance, the investment performance in the United States has improved. As time passes, particularly with the prospect of reduced trade uncertainty, it will become more possible to identify the component of growth due to the permanent reforms in the TCJA.

Conclusion

Prior to the enactment of the TCJA, the U.S. tax code hadn’t been overhauled in over 30 years. The tax code was widely viewed as broken – a conspicuous drag on the economy that chased U.S. firms overseas while suppressing investment here at home. Major elements of the TCJA, particularly the lower corporate tax rate, expensing of qualified equipment, and the broad architecture of the international reforms, should improve the investment climate in the United States. How much of the recent improvement in economic performance can be attributed to the TCJA? As a matter of economic science, it is certainly too soon to say, but there are good reasons to credit the new law.

Notes

[1] The views expressed here are my own and not those of the American Action Forum. I have benefitted enormously from numerous discussions with my colleague Gordon Gray.

[2] This section relies heavily on my testimony before this committee on March 27, 2019.

[3] See: https://waysandmeans.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/20160525TP-Testimony-Holtz-Eakin.pdf

[4] http://americanactionforum.org/research/economic-and-budgetary-consequences-of-pro-growth-tax-modernization

[5] PricewaterhouseCoopers (2011). Global Effective Tax Rates. Washington, DC

[6] https://taxfoundation.org/territorial-tax-system-oecd-review/

[7] http://businessroundtable.org/sites/default/files/reports/Diamond-Zodrow%20Analysis%20for%20Business%20Roundtable_Final%20for%20Release.pdf

[8] http://www.americanactionforum.org/research/economic-risks-proposed-anti-inversion-policy-update/

[9] https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/documents/Tax%20Reform%20and%20Wages.pdf

[10] Kevin A. Hassett and Aparna Mathur, “Taxes and Wages,” American Enterprise Institute Working Paper No. 128, June 2006.

[11] https://www.irs.gov/statistics/soi-tax-stats-individual-income-tax-returns-publication-1304-complete-report#_pt1

[12] Richard Rubin and Theo Francis, “Trump Promised a Rush of Repatriated Cash, But Company Responses Are Modest,” The Wall Street Journal, September 16, 2018, https://www.wsj.com/articles/companies-arent-all-rushing-to-repatriate-cash-1537106555

[13] Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.5, January 30, 2020.

[14] Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.6, January 30, 2020.

[15] Bureau of Economic Analysis, Table 1.1.6, January 30, 2020, and CBO, “An Update to the Budget and Economic Outlook: 2017 to 2027,” Supplementary file: 10-Year Economic Projections, June 2017.