Weekly Checkup

July 7, 2023

Oh Me, Oh MI(PS)

Before the July 4th break, the House Energy and Commerce Committee held a hearing on the Medicare Access and Chip Reauthorization Act (MACRA) of 2015 to review the program’s effectiveness and identify areas for potential reform—specifically around the merit-based incentive payment system (MIPS). So, let’s review what MIPS is and the key areas of concern.

To begin, MIPS was created as part of MACRA in 2015 to replace the sustainable growth rate (SGR) used since 1996 to determine the Medicare Physician Fee Schedule (PFS) update. SGR’s formula was designed so that if cumulative real expenditures outpaced cumulative spending targets, payment rates were automatically cut until the two were equal. This became a problem in 2002, when the PFS faced a 4.8 percent cut. Every year after, the PFS under SGR required cuts as well. To address the cuts, Congress passed annual legislation (the “doc fix”) to override the SGR cuts (which were growing every year) until 2014, when legislation was passed that would maintain PFS rates at 2014 levels until 2015. When that legislation was set to expire in 2015, physicians faced a massive 21 percent cut. To fix this, Congress passed MACRA in 2015, with MIPS becoming a permanent solution to the annual SGR “doc fix” beginning in 2019. MIPS represented a shift to quality-incentivized payments, with Medicare looking to move slowly away from its traditional fee-for-service model. MIPS would factor in quality measurements, resource use, clinical practice improvement activities, and meaningful use of electronic health records in determining payments to physicians.

That was all well and good, except that under current budget neutrality laws, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) was statutorily required to provide an updated increase of below 0.15 percent in 2019 and 2020, while both 2021 and 2022 saw statutory increases of 0.0 percent, and under current statute the 0.0 percent increase will continue through 2025. Congress has routinely overridden these updates, but these actions just kick the can down the road. Now, physicians are pushing for what is functionally an end to statutory budget neutrality in PFS payments, calling for, among other things, payment updates to be tied to the Medicare Economic Index (a measure of inflation for physician services), ensuring a yearly increase. At the above-mentioned hearing, members of Congress on both sides of the aisle called for Medicare payments to simply match commercial payments – a huge win for doctors.

Doctors certainly deserve to be compensated fairly for their services, and payment updates will always be needed. But Medicare spending grew 8.4 percent to over $900 billion in 2021 (the most recent available data), while combined public and private physician and clinical services spending increased by 5.6 percent in the same year. In the third quarter of 2021, the Medicare Economic Index had grown 4.0 percent since its 2017 base year. The bottom line: Inflation-based updates are functionally unaffordable for a program where Part A is on the brink of insolvency. Matching commercial rates (which outpaced Medicare spending in 2021 by 130 percent) would only lead to further debt for the Part B program, which is facing annual cash deficits of $360 billion in 2023. Reforms to MIPS that don’t address long-term Medicare cost issues are simply piling more debt onto an already unsustainable program, not “fixing” anything.

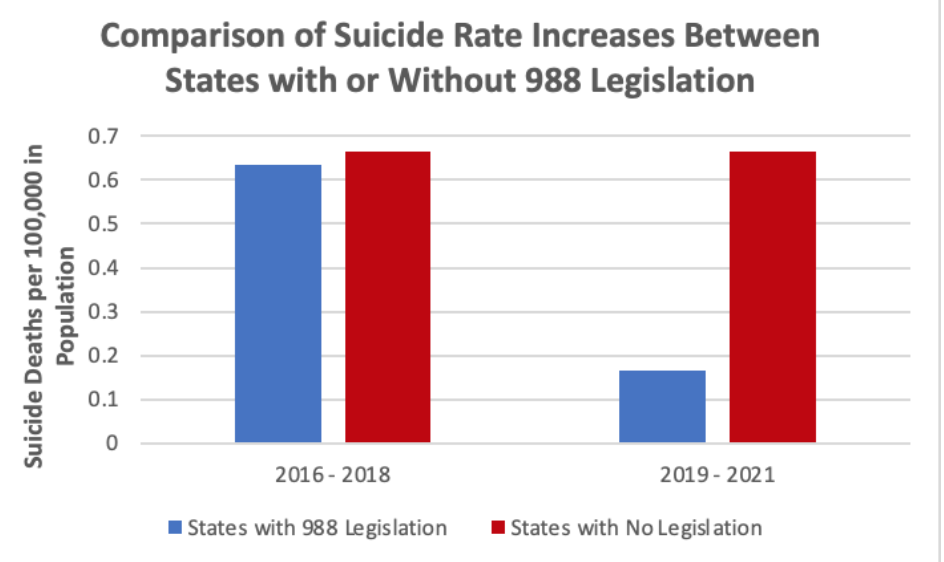

Chart Review: State Implementation of a 988 Suicide Prevention Hotline During COVID-19

Aditya Sridharan, Health Care Policy Intern

The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act of 2020 designated 988 as the official national suicide hotline number starting in July 2022. Until then, states were responsible for implementing the number—including training staff and integrating it with 911. As of October 2021 (the latest year for which suicide rate data was available), only nine states had implemented 988 legislation. Notably, these nine states experienced less of an increase in suicide rates during COVID-19 than states without 988 legislation. Between 2016–2018, the 41 states that did not implement 988 legislation experienced an average increase over two years of 1,814 deaths, while states that eventually implemented legislation saw an average increase over two years of 339 deaths. Between 2019–2021, the average two-year increase for the 41 states without 988 legislation increased to 1,842 deaths, while the average two-year increase for states that had implemented 988 plans dropped to 91 deaths. While it is possible the states that implemented a 988 number may have also implemented other initiatives to prevent suicides, or had less risk factors stemming from COVID-19 policies, this trend is worth noting.

Sources: CDC