Weekly Checkup

July 22, 2022

Putting the Reconciliation Bill in Perspective

After years of the American Family Plan, the American Jobs Plan, the Build Back Better Plan, the Build Back Better Act, and the what-can-we-get-Joe-Manchin-to-agree-to-this-week proposals, we have lost all perspective on what the Senate Democrats are actually trying to pass into law and how they are planning to do it. Let’s take a step back.

At the 50,000-foot level, the rumored reconciliation proposal is to use drug pricing provisions to cut Medicare drug spending by $200 billion or so in order to pay for two years of richer health insurance subsidies under the Affordable Care Act (ACA). These are the costs and benefits of the proposal, respectively.

The benefits are negligible. The enhanced subsidies have been in place for two years already and accomplish nearly nothing at great expense. The net increase in the number of insured was a modest 800,000; in the main the impact is to shuffle the already insured out of Medicaid and employer insurance and into ACA insurance. Is that really a good idea?

The costs are daunting. They may not seem that way because they started as H.R. 3 (which one should think of as a hydrogen bomb dropped on the life-sciences industry), which was “softened” in the original Build Back Better Act, and now is advertised as even less aggressive (think of a conventional projectile) in the reconciliation effort. But the provisions will still permanently damage the development of innovative drugs and therapies, and the precedents being set are even worse. More on that below.

The substance fails a benefit-cost test, which explains why Democrats have resorted to a shameful use of the reconciliation process. Recall that reconciliation was created to permit purely budgetary legislation to avoid a Senate filibuster and pass with a simple majority. There is literally no budgetary objective in play at present. All the taxes and spending cuts will be devoted to new spending. This is about punishing drug companies and marching toward a single-payer health system.

With that as context, let’s strap on a Dramamine patch and take a closer look at the drug provisions. The reconciliation package requires the secretary of Health and Human Services (HHS) to “negotiate” Medicare prices for 10 drugs in 2026, 15 in 2027 and 2028, and 20 in 2029 and beyond. The drugs must be single source (no generic or biosimilar), have been on the market for seven years (small molecule drugs) or 11 years (biosimilars), and be in the top 50 of spending on Medicare drugs. If you think that this is a real negotiation, or even a fair fight, think again. The bill specifies that “The Secretary’s determination that a drug is negotiation-eligible is not subject to administrative or judicial review.”

Now, comes the good part. If the secretary decides the manufacturer is not negotiating in good faith and refuses to agree with HHS, it would be subject to an excise tax ranging from 65 percent to 95 percent of its sales of the drug. Because the tax rate is based on the price inclusive of the tax, the effective rate on the net price starts at over 100 percent. It is a death sentence for the drug and the HHS secretary is judge, jury, and executioner. Just to be sure, the bill places limits on appealing the excise tax.

Speaking of 100 percent tax rates, reconciliation levies one on all drug price increases that exceed the general rate of inflation. This nifty idea has been around for years and is, generally, just an incentive to launch a drug at a higher price to avoid future increases. At present, it is ironic because drug prices have failed to keep up with the disastrous general inflation created by the last reconciliation bill (the American Rescue Plan).

So, just in case you lost the plot in this long-running horror, it is simple: The reconciliation bill doesn’t pass muster in its intent, shouldn’t pass muster in using the reconciliation process, and represents a migration by Democrats from voting for destructive inflation to voting for destruction of innovation.

Chart Review: COVID-19 Vaccine Provider Availability Among Children

Evan Turkowsky, Health Care Policy Intern

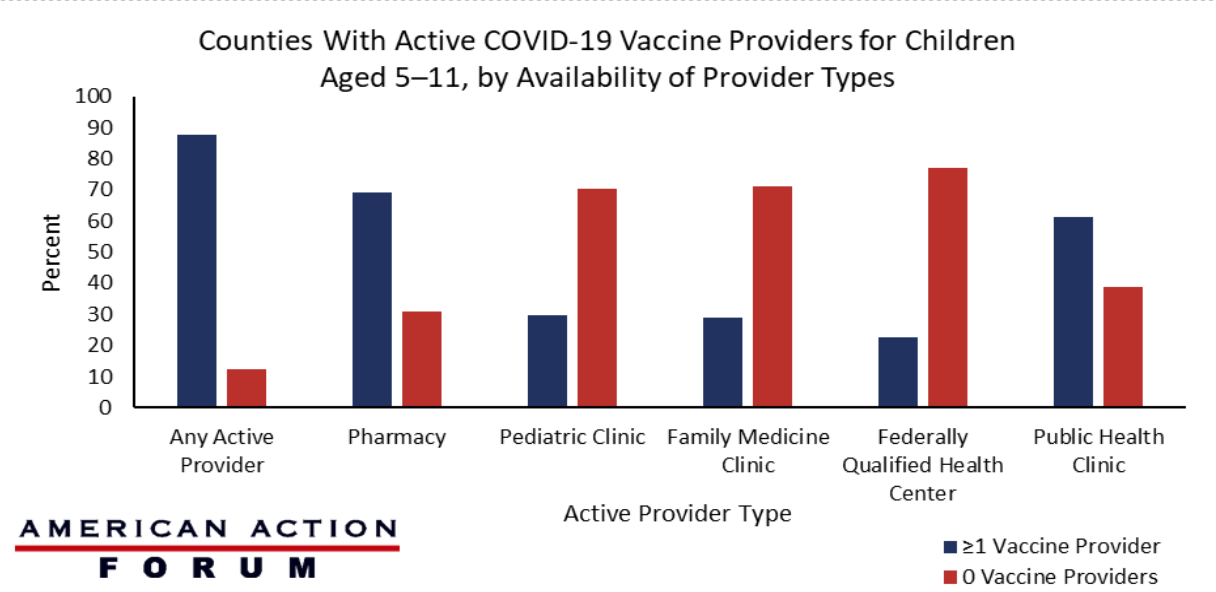

On July 1, nine months after the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) expanded its COVID-19 vaccination recommendation to children 5–11 years old, the agency released its report on vaccine availability for this age group at the county level. Of note, this report found that the accessibility of any active COVID-19 vaccine provider in a county was associated with a higher level of vaccination coverage among children in this age group.

Meanwhile, the CDC reported that as of July 6, just 36 percent of children aged 5–11 have received at least one dose of the COVID-19 vaccine and only 29.0 percent have completed the two-dose vaccination series. As seen in the chart below, among the 2,589 counties assessed, 87.5 percent had at least one active provider of the COVID-19 vaccine, with the most common provider types being pharmacies and public health clinics. The report stated that 69.1 percent of counties had at least one pharmacy actively administering the COVID-19 vaccine and 61.3 percent of counties had at least one public health clinic that could offer the shot. The least common active provider types able to offer the vaccine were family medicine clinics, of which 29.0 percent of counties had at least one, and federally qualified health centers, of which 22.8 percent of counties had at least one.

Data Source: The CDC Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report