Weekly Checkup

November 13, 2020

The New Health-Policy Landscape – Same as the Old

Welcome to the new health policy legislative landscape, same as the old health policy legislative landscape. As the dust settles and most of America prepares to move on from the 2020 election results, it’s striking how little the legislative landscape has really changed for health policy since November 2010. On paper replacing the Trump Administration with a new Biden Administration dramatically shifts the state of play in health policy, but in practice the changes will be more muted.

To be clear, I’m not suggesting that the incoming Biden Administration won’t be represent a hard break with Trump Administration on health care policy. On a host of issues—from Medicaid work requirements, to management of the Affordable Care Act’s (ACA) federally facilitated marketplace, to the general pro-deregulatory orientation of the outgoing administration—things will absolutely be different in the Humphrey Building. But throughout the fall campaign, the expectation was that a wining Biden campaign would almost certainly bring with it a Democratic majority in the Senate and an expansion of the current House majority. Instead, House Democrats will hold their slimmest majority in half a century, and the Senate looks likely to stay under Republican control. But even a 50/50 Senate with Vice President Harris casting the tie-breaking vote for chamber control isn’t going to be enough of a margin to move even moderately ambitious health policy legislation through the chamber. Visions of a filibuster-free sprint to roll out a new public option, expand ACA subsidies, or lower the Medicare age—much less enactment of some variation of single-payer, federally run health care—seem almost silly in retrospect. As Senator Joe Manchin is busily reminding people this week, even a slim Democratic majority in the Senate may not have been a sure thing to overturn the filibuster, pack the Supreme Court, and undertake the second major overhaul of the nation’s health care system in a decade.

Even on the administrative side, the Biden Administration will find making policy less than straightforward. Spend any time reading about the Biden transition team and health care and you’ll see a lot of talk about how the Biden Administration will focus on undoing Trump Administration regulations and executive orders, undoing funding cuts for ACA enrollment programs, and reversing the expansion of short-term limited-duration health plans. Executive orders can be overturned with the stroke of a pen, but reversing rulemaking can be a time-consuming process. And in the case of the Trump Administration’s policies toward Medicaid, in many cases the Biden Administration will have to wait for existing waivers to expire before they can wipe them away.

What’s interesting here is how normal this all has become. Gridlock has defined Washington policymaking since the 2010 mid-term elections that saw the Democrats rebuked for their overreach on several issues, most potently at the time the ACA. Even when President Trump had a Republican Senate and House, ACA repeal and replace legislation couldn’t get over the finish line, and outside of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, little in the way of major legislation was accomplished. It’s hard to think of substantial health care legislation that has crossed the finish line in the last 10 years. There is the CURES Act, which sought to boost treatment innovation, and this certainly was a valuable piece of legislation. Congress also managed not to drop the ball on any of the Food and Drug Administration User Fee reauthorizations—but that’s hardly anything to write home about.

As we look forward to a Biden Administration, it looks like more of the same for health policy. Little is likely to be accomplished legislatively, but as was the case after Obama, and now after Trump, policy through administrative action is only as durable as your electoral coalition.

Chart Review: Breaking Down the Newly Uninsured

Julia Demeester, Health Care Policy Intern

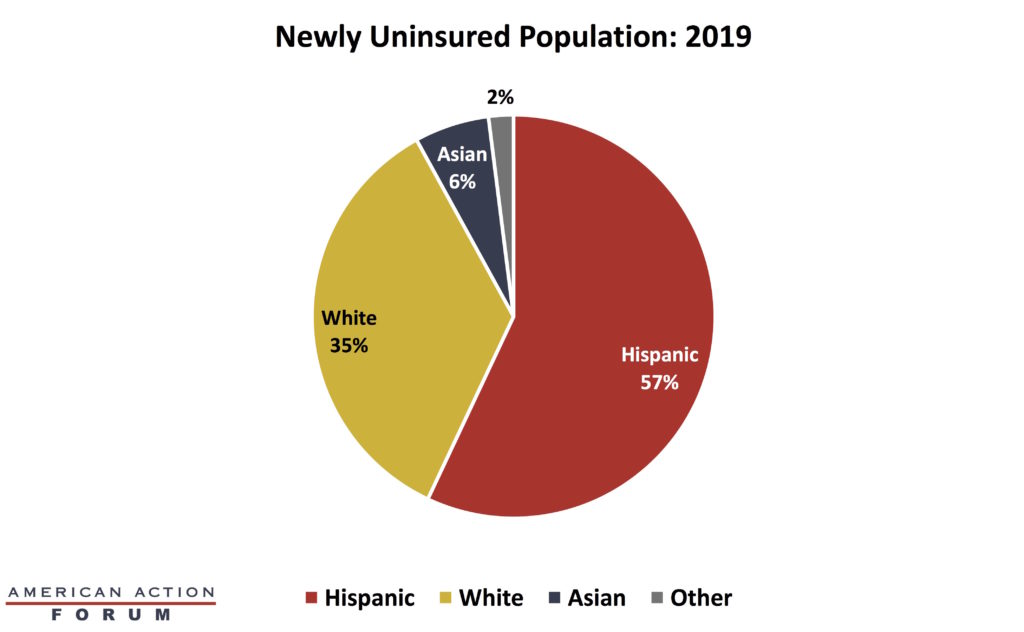

A report released by the Kaiser Family Foundation shows that the number of uninsured Americans, aged 64 and below, increased by 1 million from 2018 to 2019, the third consecutive year of increase. As a result, the number of uninsured stood at 28.9 million people. The graph below shows that most of the coverage loss was among Hispanic individuals. Approximately 57 percent of newly uninsured individuals were Hispanic, over 612,000 people, including roughly 217,000 children. While it is unclear how the pandemic has impacted the uninsurance rate, and some initial estimates indicate the impact is small, it is likely the rate has risen at least somewhat this year.

Worth a Look

New York Times: Measles Deaths Soared Worldwide Last Year, as Vaccine Rates Stalled

The Hill: Proportion of pediatric emergency room visits for mental health increased sharply amid pandemic