Weekly Checkup

September 25, 2020

The COVID-19 Pandemic’s Impact on Insurance Coverage

Ever since 22 million people lost their jobs in March and April, there has been appropriate concern about the implications of this pandemic-driven job loss on health insurance coverage. Considering that roughly 56 percent of the U.S. population receives insurance through their employer, a substantial loss of employer-sponsored insurance (ESI) could trigger a large increase in uninsured rates at the same time that the country grapples with a global health pandemic—hardly an ideal situation. As a result, there have been a number of proposals over the last few months for addressing this assumed insurance loss. But how many people have actually lost their health insurance because of the COVID-19 layoffs?

The honest answer is that we don’t know yet, and the lag time in the data means we won’t know for a while. We are, however, starting to get a sense from survey data, and a number of studies over recent months have attempted to document the scope of the problem. The Kaiser Family Foundation (KFF) estimated in May that 78 million people were part of households that lost ESI because of the pandemic. That’s a staggering number considering the Census Bureau estimates somewhere between 26.1 million and 29.6 million people were uninsured in 2019, but the more KFF parsed the numbers, the narrower the scope of the problem appeared. Taking into account other household offers of ESI, eligibility for Medicaid, and the availability of subsidies for individual market insurance under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), KFF found that only 5.7 million people would not qualify for federal assistance or another offer of ESI, and most of those were in households with income over 400 percent of the federal poverty level (FPL). A second report, released in July by the Urban Institute, projects that around 3.5 million people will be left without insurance coverage at the end of the year because of the pandemic and related job loss.

AAF President Douglas Holtz-Eakin testified before the House Energy and Commerce Health Subcommittee this week regarding this topic, and in addition to reviewing these studies, he also looked at recent results from the Census Bureau’s Household Pulse Survey. What he found is that there has been virtually no change in the rate of the uninsured reported over the first half of 2020; in fact, it decreased 0.6 percent.

Ultimately, the available data is insufficient to give us a clear picture of the total impact of the pandemic on insurance coverage, but what we can see is encouraging: Far fewer Americans appear to have ended up uninsured because of the pandemic than has been widely feared. Certainly, many millions of Americans have lost ESI, but that hasn’t left most of them without options. Between Medicaid, subsidized individual market coverage, other offers of ESI, short-term limited-duration insurance, and COBRA, most Americans who have lost coverage appear to have found a readily available alternative.

All this isn’t to suggest that we should be unconcerned with those Americans who have truly been left without affordable options for insurance coverage, but our solutions should be narrowly tailored. Some have argued for dramatic expansions of existing federal health programs or the establishment of new ones to address the insurance needs left in the wake of the pandemic’s economic impact. It doesn’t appear, however, that the problem is widespread enough to merit such dramatic action.

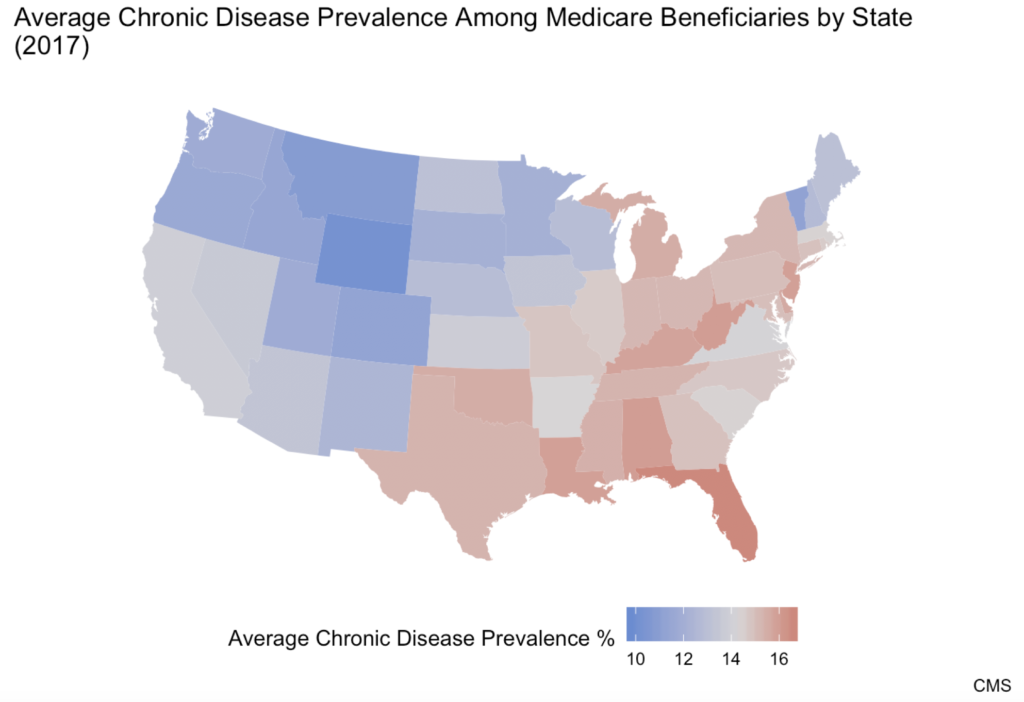

Chart Review: The Geographic Distribution of Chronic Disease

Although chronic disease affects approximately half of the U.S. population, there are parts of the country facing a far higher burden than others, note AAF’s Director of Human Welfare Policy Tara O’Neill Hayes and Serena Gillian in their recent research. The chart below displays the distribution of chronic disease among Medicare beneficiaries in the United States. Each state has been given its own average chronic disease prevalence value, calculated by summing the proportions of Medicare beneficiaries suffering from each of 21 different chronic diseases in a state and dividing the sum by 21, the total number of chronic diseases measured. The highest prevalence of chronic disease is concentrated in the Mid-South region. The state with the highest average chronic disease prevalence—16.6 percent—is Florida. The state with the lowest average chronic disease prevalence is Wyoming at 9.8 percent.

Worth a Look

Wall Street Journal: Here’s How the Pandemic Is Affecting PTSD Rates

Reuters: AstraZeneca gets partial immunity in low-cost EU vaccine deal