Weekly Checkup

August 2, 2019

The Sound and Fury on Drug Importation

This week, the Trump Administration announced the “Safe Importation Action Plan” to allow the importation of drugs from Canada and possibly other countries. While some Trump Administration officials have previously dismissed the idea as a gimmick at best and dangerous at worst, President Trump has long been a champion of the concept. It is worth examining several details of the proposed policies to understand what the likely impact will be.

The proposal lays out two pathways for drugs to enter the United States from abroad. The first pathway would use existing legal authority to allow states, wholesalers, and pharmacies to apply for demonstration projects in which they would import drugs from Canada, to take advantage of the lower Canadian prices.

We’ve covered in past Weekly Checkups why the Canadian government might stymie these activities, but for now let’s assume no pushback from our friends to the north. The demonstrations would have two requirements. First, the applicant would have to implement a host of safety and security measures to guarantee the medication is safe. Second, they’ll have to demonstrate real savings for patients. That second requirement might seem easy—it’s well known that Canadian drugs are cheaper—but the first requirement will bring overhead costs. These drugs won’t come to U.S. patients at Canadian prices; they’ll come at Canadian prices plus a markup to cover all the other compliance costs. Whether that final price offers any savings remains to be seen.

Next, the selection of drugs eligible for this policy raises questions. Any FDA-approved drug is eligible for importation—except for controlled substances, biologics, infused drugs, intravenously injected drugs, drugs inhaled during surgery, any drug with a risk evaluation and mitigation strategy in place, and so on. In other words, everything except the expensive treatments can be imported.

The second pathway would allow manufacturers to import versions of their own drugs that were intended for sale in other countries. Imagine I manufacture a drug in India. Some are packaged for the United States, while some are packaged for France. The drugs going to France cost less, because the French government says they have to. Under this forthcoming guidance, I could slap a U.S. label on top of the French label and sell the drug in the United States at the French price (using a new drug code to distinguish the French version from the original). Why would I do this? Great question; I’m not sure.

The administration argues this second pathway would allow manufacturers to get around pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) contracts that might force them to sell drugs at a higher price. But this pathway does not eliminate PBMs as gatekeepers; effectively the only people it would benefit are those who are willing to pay for their drugs apart from any insurance (meaning the cost of the drug would not count toward their deductible). The administration insists that drug manufacturers have been calling for this change. My daughter has been telling me for years she has a pet unicorn. I have yet to see any evidence that either claim is true.

Finally, the timeline: There are plenty of weedy implementation questions outstanding, and administration officials have been forthright that this announcement is the beginning of a lengthy process, so it’s tough to say exactly when any importation policy might take effect. This week was really an announcement of intent to propose a rule that might eventually be finalized. With that in mind, my best guess for any implementation is fall 2020.

The fact that drugs cost less in Canada than the United States is frustrating, but the disparity exists because the two countries have made different choices about policy tradeoffs. Canada’s single-payer system denies patients access to medications if manufacturers don’t agree to sufficiently low prices. In the United States, we’ve chosen to prioritize access over cost, leaving determinations about treatment to patients and their medical providers rather than government accountants. That’s a broad simplification of a complex policy challenge, but it provides the basic contours of what’s at stake in this debate.

Importing drugs from Canada is risky, potentially for safety, but certainly for access. This policy does little to change those dynamics.

Chart Review

Ryan Haygood, Health Care Policy Intern

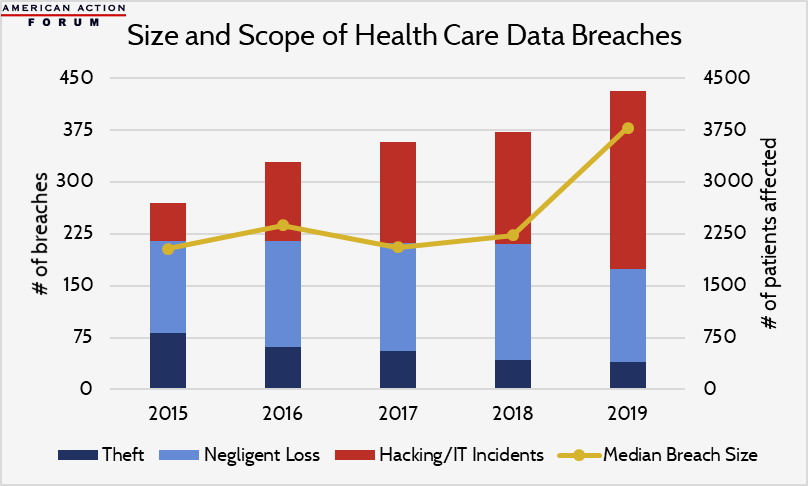

Electronic Health Records (EHR) have rapidly displaced traditional pen-and-paper documentation over the last decade. To date, the U.S. government has spent over $35 billion to incentivize EHR uptake and imposed Meaningful Use Requirements. As a result, today nearly all hospitals and some 9 in 10 office-based physicians use an electronic system. Full integration of interoperable EHR systems promises huge savings—over 2 percent of total health care spending, according to one estimate—but the increasing prevalence of EHR has also contributed to growing rates of health care data breaches. These breaches threaten patient privacy and may cost compromised hospitals $15 million per breach—nearly double the average cost in other industries. The typical breach size is projected to rise 70 percent this year, commensurate with the projected growth in the number of hacking-related breaches, which typically jeopardize many more patient records than theft and negligent loss.

Data are from the Department of Health & Human Services; 2019 estimate is a modified projection through the end of the year.

Worth a Look

Reuters: Superbugs found lurking in London underground and hospitals

New York Times: Would You Want a Computer to Judge Your Risk of H.I.V. Infection?