Weekly Checkup

December 12, 2025

Words Matter: Cost Versus Price in the Health Care Debate

When politicians promise to “lower health care costs,” they’re usually talking about prices. That distinction matters more than it sounds. In economics, cost and price are related but not interchangeable concepts – and blurring them leads to bad policy and confused public debate.

Cost is about resources. It captures what it takes to produce a good or service: labor, equipment, facilities, supplies, time, and the “opportunity cost” of how those resources could otherwise have been used. Costs are fundamentally about real inputs.

Price, by contrast, is what someone actually pays (or is billed) for that good or service. It’s a number on an invoice or explanation of benefits, shaped by market power, regulation, cross-subsidies, and negotiation. Prices determine who pays and how much – not how many nurses are needed on a floor or how many hours a surgeon spends in the operating room.

You can lower prices without lowering underlying costs. For example, the government can cap what insurers pay hospitals or force drug manufacturers to accept lower reimbursement. That may reduce premiums or out-of-pocket bills in the short run, but unless the actual cost of providing care changes, the system has the same (or greater) resource burden. The gap must be made up somewhere: reduced investment, lower wages, fewer services, or higher prices for someone else.

Health care makes this distinction especially messy because there are multiple prices layered on top of the same underlying cost. Take a hospital visit. The cost includes the health care provider’s salary, the depreciation on the MRI machine, the electricity, malpractice coverage, administrative overhead, and more. But the prices you see are:

- The hospital’s “chargemaster” rate (almost no one pays this).

- The negotiated rate with a commercial insurer.

- Medicare or Medicaid’s administratively set payment.

- The patient’s out-of-pocket obligation (copay, coinsurance, or deductible).

All of these different prices account for the same underlying bundle of costs.

Policy debates often treat any change in who pays as a change in costs. Move more spending onto taxpayers through subsidies or public coverage? That can make premiums or point-of-service bills cheaper, but total system costs may be unchanged or even higher. Cap out-of-pocket spending for patients without changing underlying payment rates or delivery models? You’ve shifted financial risk from patients to insurers or government, but you haven’t made care less resource-intensive.

The reverse is also true: You can reduce costs without immediately lowering prices. If a health system invests in better care coordination, fewer readmissions, or more appropriate use of diagnostics, the true resource cost of caring for a population might fall. But if payment contracts don’t share those savings with purchasers or patients, the price may not move much – at least not right away.

So when policymakers say they want to “bend the cost curve” in health care, they should be precise. Are they trying to reduce the real resources required to deliver care? That implies changes in technology, delivery models, and regulation. Or are they mainly trying to reduce prices paid by a particular group – taxpayers, employers, or patients – by shifting who writes the check?

Both goals can be legitimate. But conflating cost and price leads to policies that celebrate lower premiums or copays while leaving the underlying system just as expensive – and potentially more unstable. In health care, clarity on this basic distinction is the first step toward reforms that actually make care more efficient, not just differently financed.

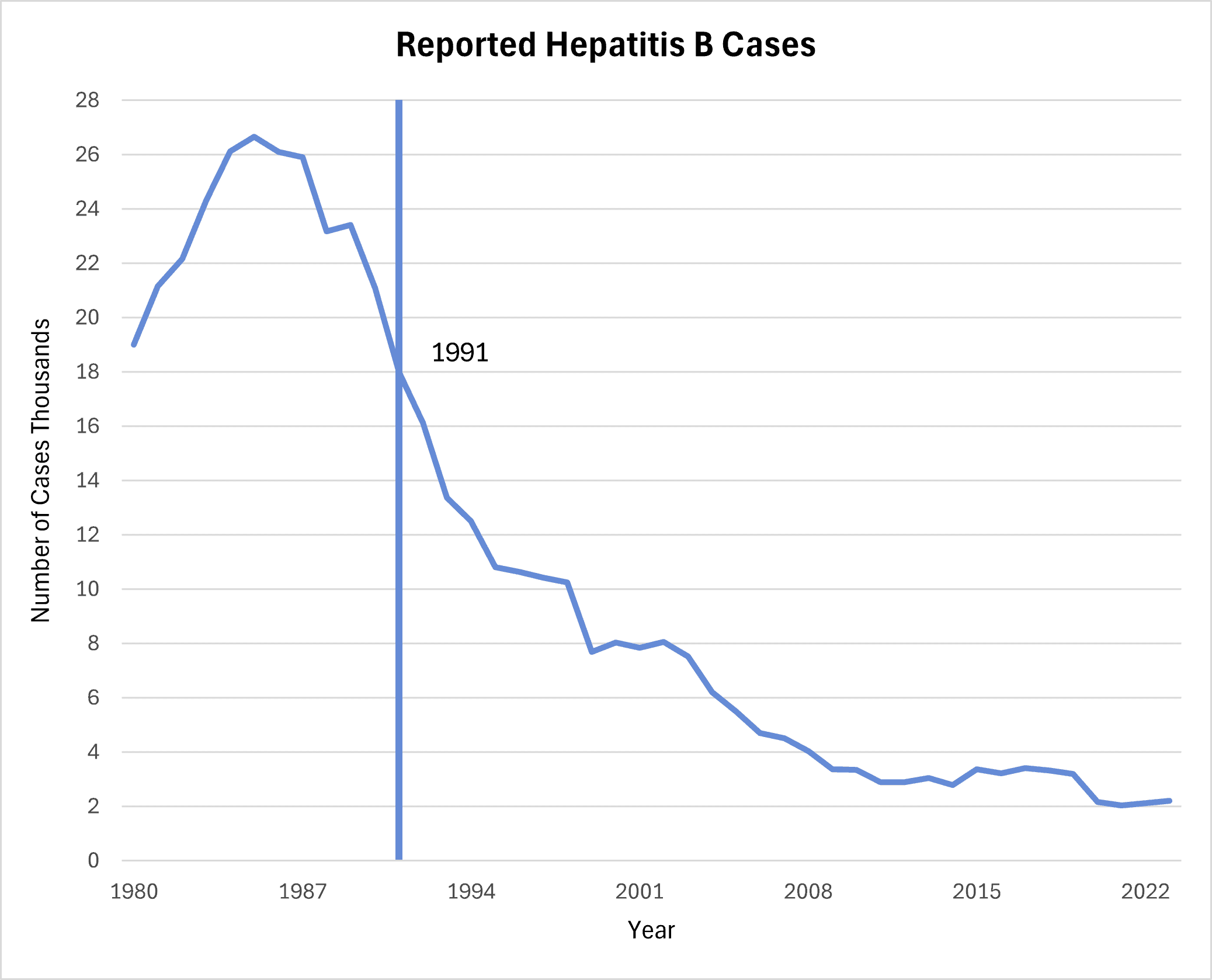

Chart Review: Hepatitis B Vaccines Have Reduced the Annual Number of Cases

Jack Leimann, Health Care Policy Analyst

Last Friday, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) – the committee responsible for providing recommendations on the use of vaccines in the United States – voted to begin recommending “individual-based decision-making for parents deciding whether to give the hepatitis B [Hep B] vaccine, including the birth dose, to infants born to women who test negative for the virus.” This removes the previous recommendation of universal birth doses. As illustrated in the chart below, data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that the U.S. experienced a decline in documented cases of Hep B since the approval and widespread distribution of a Hep B vaccine in 1986, and after 1991 when the Hep B vaccine was first included in the infant vaccination schedule.

The proposed changes to the childhood vaccination schedule could contribute to increased case counts in the future. Babies may encounter non-mothers that have an unknown Hep B status. Approximately 50–70 percent of people with Hep B are asymptomatic; exposure to asymptomatic carriers leaves unvaccinated babies vulnerable to contracting Hep B. Studies show that delaying the Hep B birth dose by two months may lead to over 1,400 excess Hep B childhood infections.