Research

July 19, 2017

The Outlook for Defense Spending: FY2018

The Outlook for Defense Spending: FY2018

Executive Summary

- Under current law, base defense funding will face a nominal cut of about $2 billion in FY2018 due to spending restrictions imposed by the Budget Control Act (BCA).

- The president’s budget, the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, as well as the House budget resolution all provide for defense funding levels above the BCA cap.

- Amending the BCA to allow for higher defense funding in FY2018 and beyond will require a change in law and will thus require a bipartisan compromise, likely in the mold of past Bipartisan Budget Acts.

Recent Trends in Defense Funding

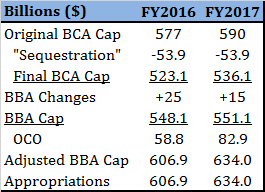

On November 2, 2015, President Obama signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2015 (BBA), which established discretionary spending levels and enforcement provisions, for FY2016 and FY2017. The BBA provided relief to both defense and domestic discretionary spending from spending caps put into place by the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA).[1] The BBA set defense caps for FY2016 and FY2017 at $548.1 billion and $551.1 billion, respectively, with allowances for adjustments to accommodate additional funding for overseas contingency operations (OCO) and emergencies. These revised caps reflect increases of $25 billion and $15 billion for FY2016 and FY2017, respectively, compared to the spending levels set forth under the BCA. For both FY2016, and FY2017, appropriations have hewed to the caps established under the BBA (Table 1).[2]

Table 1: Status of Recent Defense Spending Limits and Appropriations

The Outlook for Defense Spending for FY2016 and Beyond

The BBA only covered two years, meaning that a lower spending cap of $549.1 billion will be in effect in FY2018. In exchange for the relatively modest increases in defense funding over the BCA-set spending caps, the BBA also increased non-defense discretionary funding by equal amounts per President Obama’s insistence.[3] The Trump Administration dropped this framework in its first budget, and proposed increasing the FY2018 cap by $53.9 billion.[4] Congressional budget writers are also expected to increase defense spending above the current-law cap without matching domestic spending increases.

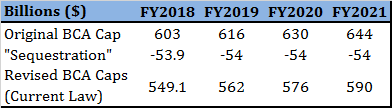

For FY2018, the original BCA cap was set at $603 billion, but is currently set at a post-“sequestration” level of $549 billion. The spending caps grow modestly through 2021 (Table 2). Thus, under current law, base defense funding would decline in nominal terms from FY2017 levels.

Table 2: Original and Post- “Sequestration” Defense Discretionary Funding Caps[5]

Compared to the original BCA caps, the downward revision on the defense discretionary spending caps owing to the failure of the “Super Committee” amounts to $216 billion over the next 4 fiscal years.

Possible Policy Approaches to Defense Spending

The Trump Administration, and many in Congress, have signaled their intention to increase the defense spending cap for FY2018 and beyond.

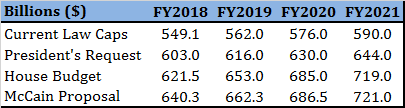

The president’s FY2018 budget has proposed to eliminate the reductions in the BCA defense caps attributable to sequestration in FY2018 and grow the defense cap at 2.1 percent thereafter – essentially eliminating the sequestration-level defense cap (Table 3).[6] The House Budget Committee’s FY2018 budget resolution provides $621.5 billion for defense funding.[7] The Armed Services Committees in both the House and the Senate have completed work on the National Defense Authorization Act for 2018, which also call for defense funding above current levels. Senator John McCain, the chairman of the Senate Armed Service Committee released an expansive report calling for defense funding levels well above both current law and the president’s budget request.[8]

Table 3: Current Law and Alternative Approaches

The Budget Control Act remains the primary determinant of defense funding. Absent a change to the BCA caps, even if Congress appropriates more funding, the administration’s Office of Management and Budget would have to cancel any budget authority appropriated above the cap. As a result, any potential for relief from the spending caps must involve a change to the BCA itself, as was required with the BBA. Accordingly, relief from the cap would require several steps.

The first step in this process was the president’s budget, which signaled the administration’s intentions to increase the BCA caps and presented the administration’s request for defense resources above current-law levels.

Congress is now in the process of formulating and deliberating on the budget resolution. In formulating a budget resolution, Congress agrees to discretionary spending levels – enforceable through points of order which can be waived with super-majorities.[9] The House budget resolution would seek to increase defense funding by $72.9 billion over the current law level of $549.1 in FY2018. While the Senate has not yet proposed a budget resolution, it is likely to assume an increase in the defense cap as well. The importance of establishing a defense funding level for FY2018 in the budget resolution is two-fold: it is important to cement bicameral agreement in advance of debate on the defense appropriations measure. It is also important procedurally, if a budget resolution assumed defense funding at levels consistent with the cap, a subsequent defense appropriations bill that violated the level in the budget resolution could be subject to a point of order, which would require 60 votes to waive.

While it is important to the process that the House and Senate agree to a budget with higher defense funding levels, that agreement is insufficient for providing for greater defense funding. First it is important to remember that a budget resolution is often a partisan document, and rarely receives the support of the minority. Accordingly, it is not a meaningful vehicle for developing bipartisan agreement. Second, the president does not sign a budget resolution, so it is not an appropriate vehicle for engaging with the executive branch. Last, to ultimately fund national defense above the discretionary spending caps will require the passage of two changes in law – a funding bill and a change to the BCA. Both will face 60-vote thresholds during deliberation in the Senate. Accordingly, shielding a defense appropriations bill from a budget point of order is less meaningful.

A key element of many budget resolutions is the inclusion of reconciliation instructions. Reconciliation is an optional legislative process that allows for the filibuster-proof consideration of legislation that achieves budget outcomes specified by the budget resolution. Special rules, however, limit the type of legislation that may be passed through reconciliation. Key among these limitations is the “Byrd Rule,” which among other restrictions, precludes inclusion in reconciliation bills of any provision that does not change spending or revenues. Changes to the spending caps would not change spending or revenues, and this could not be altered through reconciliation. The spending caps themselves have no effect on spending levels. Rather, the appropriations acts that adhere to them do. Accordingly, the cuts to defense currently embedded in the spending limits cannot be altered through reconciliation. While the use of reconciliation in the FY2018 budget resolution is likely to focus on tax reform, the extent that any increase in the defense spending cap would have to be offset – the offsets could be achieved through the reconciliation process.[10]

The second key step in providing for relief under the current spending caps would be in the passage of the appropriations bill itself. This measure would have to reflect bicameral and bipartisan agreement in Congress, and be signed by the president. Accordingly, how the caps are adjusted matters a great deal. The dynamics of this debate have shifted considerably from the Obama position, whereby defense increases had to be matched by non-defense increases. The Trump Administration has proposed considerable reductions to non-defense discretionary spending levels, $1,559 billion over 10 years, that would more than offset the increase in defense funding.

Congressional policymakers are unlikely to pursue a similar policy.

Rather, the increase in the caps and the associated increase in defense spending would likely have to be offset through mandatory spending. This reflects several important dynamics. First, the Republican Congress has no appetite for tax increases, and any such measures would be unlikely to receive any support. Second, non-defense discretionary spending has already been cut along with defense spending, and congressional Democrats, in particular, would be unlikely to assent to finance higher defense spending with further reductions in non-defense spending. Indeed, if past compromises to increase the defense cap are any indication, any increase in the caps on defense spending would likely be paired with at least some increase in the non-defense cap. As such, that dynamic leaves only mandatory spending as the available source of potential offsets.

The House budget resolution includes over $2 trillion in non-health mandatory saving, and more important, includes reconciliation instructions to 11 authorizing committees directing them to report a minimum of $203 billion in mandatory savings. The $203 billion would be adequate to fully offset the House budget’s increases in defense, relative to current law, for two years. The BCA’s discretionary caps are scheduled to remain in force through 2021. Increasing defense funding relative to BCA level-funding for its duration would cost $401.1 billion. Accordingly, fully offsetting this increase with mandatory savings would require substantial reforms to remain budgetarily neutral.

Having agreed on the right funding level and the appropriate offsets, the last step to relieving the defense cap for FY2016 would be amend the BCA to accommodate the higher level of spending. This would require a change in law that would again have to gain approval in the House, Senate, and the White House. Accordingly, this would likely be included in the funding measure itself, as was the case with the Bipartisan Budget Acts of 2013 and 2015.

Appendix: Defense Funding History and The Evolution of the Budget Control Act, American Taxpayer Relief Act, and Sequestration

On August 2, 2011, the president signed the Budget Control Act of 2011 (BCA, P.L. 112-25). The BCA re-imposed a regime of discretionary spending caps that had previously been in place through the 1990s and lapsed in 2002. The BCA provided a mechanism, an across the board rescission of budget authority, a sequester, in the event that those caps were breached.

The BCA also imposed an additional mechanism, variously referred to as the “Joint Committee Reductions,” “Automatic Spending Reductions,” or more colloquially just as the “sequester,” which was designed to reduce the deficit by $1.2 trillion (including interest costs) over and above the reductions imposed by the BCA discretionary caps. This mechanism was designed to come into force if the Joint Select Committee on Deficit Reduction, also referred to as the “Super Committee,” failed to produce a plan that reduced the deficit by equal measures. The Super Committee failed to do so, thus triggering the automatic enforcement provisions of the BCA through FY2021. The BCA required the White House Office of Management and Budget (OMB) to issue a sequestration order on January 2, 2013, cancelling $109 billion in budget authority, split evenly between defense and non-defense categories, already enacted for FY2013 – a true sequester of budget authority already in place.[11] For FY2014-2021, discretionary savings result from spending caps lowered about $90 billion per year below the original BCA discretionary caps. Remaining savings would come from cancelation of mandatory budget authority through an annual sequestration order.[12]

On January 2, 2013, (effective for January 1), the president signed the American Taxpayer Relief Act (ATRA) of 2012, which addressed a number major expiring provisions contributing to what was referred to as a “fiscal cliff.” Among these provisions was the sequestration set to take place on January 2. ATRA delayed these cuts by two months – pushing the order to March 1, 2013. It also reduced the amount to be sequestered to $85 billion, again split evenly between defense and non-defense funding.[13]

OMB issued a sequester order pursuant to ATRA on March 1, 2013, and cancelled $85 billion in enacted budgetary resources for the balance of the fiscal year. The order reduced defense funding by $42.6 billion, non-defense discretionary funding by $25.8 billion, and non-defense mandatory spending by $16.9 billion.[14]

Federal funding faced a troubled road in the remainder of 2013, including a partial government shutdown beginning October 1, 2013, owing to a failure between the House and Senate to agree to discretionary spending levels and other policy matters. On October 16 Congress passed a continuing resolution through January 15, 2014, that provided $986 billion in overall discretionary budget authority on an annualized basis for FY2014, and essentially extended FY2013 post-sequester Defense spending at $518 billion on annualized basis. However, at this funding level and in the absence of a change to the BCA, defense spending would face a $20 billion sequester in January. This is because for FY2014, the lowered spending cap for defense was $498.1 billion.[15]

On December 26, 2013, the president signed into law the Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA), which established discretionary spending levels and enforcement provisions, for FY2014 and FY2015. This was designed to add certainty to the appropriations process and avoid government shutdowns. The BBA set overall discretionary spending by a combined $63 billion above the lowered caps for FY2014 ($45 billion) and FY2015 ($18 billion). The BBA set defense caps for FY2014 and FY2015 at $520.5 billion and $521.3 billion, respectively, with allowances for adjustments to accommodate additional funding for overseas contingency operations and emergencies.[16]

[1] The spending caps in place under current law were imposed by the Budget Control Act, and essentially reflect two rounds of spending cuts: first by the imposition of initial spending caps put in place in 2011, plus further reductions subsequent to the failure of the Congressional “Super Committee,” to propose a deficit reduction plan of at least $1.2 trillion. The second rounds of cuts, shorthanded to “sequestration” imposes an annual $54 billion reduction in the defense funding caps. Thus, the current law caps were established pursuant to the BCA, they also reflect a fallback mechanism in the BCA that was not intended to take effect.

[2] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/114th-congress-2015-2016/reports/51873-Sequestration.pdf, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52704-sequestration.pdf, https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_final_january_2016_potus.pdf, https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2017_final_sequestration_report_may_2017_potus.pdf, http://docs.house.gov/meetings/RU/RU00/CPRT-114-RU00-D001.pdf

[3] https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/omb/legislative/sap/114/saphr5293r_20160614.pdf

[4] https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2018_preview_report_may2017_potus.pdf

[5] https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2018_preview_report_may2017_potus.pdf, https://www.cbo.gov/system/files/115th-congress-2017-2018/reports/52704-sequestration.pdf

[6] https://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/whitehouse.gov/files/omb/sequestration_reports/2018_preview_report_may2017_potus.pdf

[7] https://budget.house.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/07/Building-a-Better-America-PDF-1.pdf

[8] Note that the defense funding level provide in the House Budget mirrors the FY2018 level in the House Armed Services Committee NDAA, while that specified by SASC Chairman McCain in his white paper mirrors the FY2018 funding level in the SASC-reported NDAA. See https://www.americanactionforum.org/daily-dish/funding-national-security/; https://www.mccain.senate.gov/public/_cache/files/25bff0ec-481e-466a-843f-68ba5619e6d8/restoring-american-power-7.pdf

[9] http://americanactionforum.org/research/the-congressional-budget-process-what-a-budget-resolution-is-and-what-it-is

[10]For more on reconciliation, see: https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/budget-reconciliation-primer/

[11] http://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/09-12-BudgetControlAct_0.pdf

[12] ibid

[13] https://www.cbo.gov/sites/default/files/American%20Taxpayer%20Relief%20Act.pdf

[14] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/fy13ombjcsequestrationreport.pdf

[15] http://www.whitehouse.gov/sites/default/files/omb/assets/legislative_reports/sequestration/sequestration_update_august2013.pdf

[16] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/the-budget-control-act-and-the-outlook-for-defense-spending/