Insight

April 6, 2023

Baby Formula in the United States: Health and Economic Policy Issues

Executive Summary

- The United States has suffered from a baby formula shortage since February 2022, an issue occasioned by a series of supply shocks, but exacerbated by two underlying problems within the formula market generally: inadequate competition and a poor federal surveillance strategy of the production of baby formula.

- To remedy the former, import restrictions and tariffs should be eliminated to expand the pool of available suppliers, and reforms to the Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) should be enacted to enhance competition among domestic suppliers.

- To remedy the latter, the Food and Drug Administration must acquire the expertise to safely oversee the production of baby formula, which has suffered from a several health-related recalls, in the United States.

Introduction

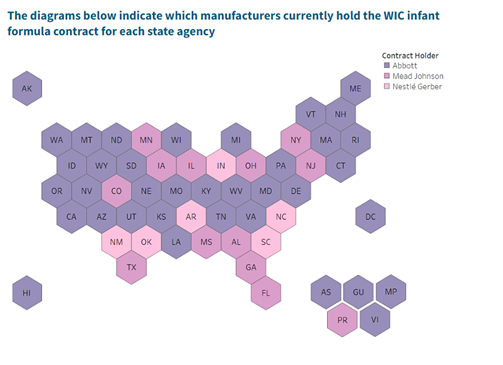

Baby formula shortages have persisted in the United States since February 2022, and attempts to spur supply chain reforms remain a bipartisan priority.[1] Recent manufacturer recalls[2] of baby formula reveal the two key problems in the domestic baby formula supply chain. First, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) lacks the appropriate expertise to oversee the production of baby formula. Second, the Department of Agriculture (USDA) Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) has inadvertently restricted market competition among baby formula manufacturers. Federal law requires WIC state agencies to competitively bid and award a single contract to a specific manufacturer. At this time, only three manufactures (Abbott, Mead Johnson and Nestle Gerber) hold single-supplier contracts, which limits competition within the baby formula marketplace. [3]

On March 28, 2023, the House Committee on Oversight Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services held a hearing on the ongoing infant formula shortage following Abbott’s February 2022 voluntary recall of its powered baby formula products (Similac, Alimentum, and EleCare). Testimony at the hearing highlighted deficiencies in baby formula manufacturing oversight in the United States, as well as a lack of FDA surveillance into cases of illness caused by product contaminated with cronobacter. This bacteria is a deadly naturally occurring “opportunist” pathogen[4] found in powdered formula which can cause meningitis and bloodstream infections in infants.

Impediments to Effective Competition in the Baby Formula Market

Improving International Supplies

To increase the number of baby formula products available during the recent shortage, Congress passed the Formula Act and the Bulk Infant Formula to Retail Shelves Act to “suspend temporarily rates of duty on imports of certain infant formula products”[5] until December 31, 2022. This suspension allowed for formula products to be sold without a tariff, which can be as high as 17.5 percent.[6] Subsequently, a White House spokesman said the tariff waivers doubled the number of manufacturers selling baby formula in the United States.[7] This provides telling evidence of a basic policy problem: Tariffs and FDA enforcement on imported formula products reduce the number of suppliers and increase the probability of prolonged shortages. Furthermore, following the suspension of these tariffs in 2022, the FDA published guidance on its enforcement discretion on these products until 2025 to ensure supply stability. The Congressional Research Service found that that USDA’s WIC contracting model has made the United States “a relatively unattractive market for foreign manufacturers, particularly of low-cost infant formula…[and that] Congress might consider encouraging mutual recognition agreements on regulatory testing and certification, or other policy instruments to reduce these trade barriers.”[8] Therefore, following the suspension of these tariffs, Congress should consider permanently eliminating these restrictions.

WIC Reforms

Beyond the levying of heavy tariffs on baby formula imports, there is also too little competition among domestic suppliers. One reason is that the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) is the largest purchaser of baby formula through its Department of Agriculture (USDA) Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants and Children (WIC) program, which covers half of all infants. The WIC program, typically administered at the state-level, requires beneficiaries to purchase formula from a single-supplier restricting market competition.[9] Only three large manufacturers hold single-supplier contracts with 89 WIC state agencies.[10] Please see below the current sole-supplier companies per state contract as identified by the USDA.

To maximize rebate savings, WIC state agencies bid among manufacturers and then award a contract to a single manufacturer to provide formula to their specific beneficiaries. The USDA states that this bidding and contracting process saves the WIC program $1.7 billion per year. To promote savings while also encouraging competition, Congress cannot solely look to increase transparency into WIC contracting,[12] but also look to other contracting incentives outside the single-supplier rebate contract.

Improving the Health Surveillance

The FDA lacks the expertise to safely oversee the production of baby formula.[13] The agency does not currently provide guidance to manufacturers on preventing contamination from cronobacter, a deadly pathogen found in powdered formula. Of note, the agency may not be aware of contaminated products because this pathogen is not listed as a notifiable disease. If a disease is deemed notifiable, all 50 state health departments, New York City, the District of Columbia, and all U.S. territories are required to be notified of confirmed cases.[14] Since cronobacter is not listed by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) as a notifiable disease, the number of cases, although limited,[15] may be underreported.[16] Surveillance and inspection of the production of baby formula, studies have shown, would better ensure the safety of these products.[17]

In addition to having information on the prevalence of the bacteria, the FDA needs improved expertise. In a 2022 report, the FDA acknowledged that it must “hire and train the requisite expertise to better understand the specific challenges presented by infant formula and broaden the scientific understanding of cronobacter in particular.” Currently, baby formula manufacturers are not required submit cronobacter information to the FDA. If manufactures were required to submit this information to the FDA, however, the agency could potentially better understand the pathogen and identify outbreaks of the disease.[18]

Conclusion

Recently, the FDA ended the importation of formula, and USDA’s WIC program rolled back flexibilities beneficiaries could use to purchase formula outside the single-supplier contract, temporary reforms that were necessary to ease the severe shortage of these products. Without these agencies’ restrictions, the market could have more quickly responded to the shortage. Congress should act to suspend at least some of these restrictions to ensure the U.S. supply chain is able to fulfill the needs of the domestic marketplace.

Congress, the Biden Administration, and several federal agencies are working on different strategies to improve the baby formula supply chain. Further actions or strategies should bring together these groups to ensure that resources are being effectively coordinated to prevent future supply chain disruptions, as well as foster a competitive baby formula marketplace by permitting purchasing flexibilities in the USDA WIC program.

[1] The Access to Baby Formula Act passed the Senate in 2022 by unanimous consent. The House voted 414-9.

[2] The U.S. shortage of baby formula, which peaked in 2022, continues as the FDA announced Gerber’s voluntary recall of their products (due to cronobacter contamination) in March 2023

[3] Catherine Rampell, “Baby-formula tariffs are about to return, risking fresh shortages,” The Washington Post. Rampell stated that “Before Abbott’s Sturgis plant shut down, four companies dominated the U.S. infant formula industry, accounting for roughly 90 percent of the market.”

[4] According to the FDA, cronobacter “is a germ (bacteria) that is naturally found in the environment. Cronobacter can exist on almost any surface and is especially good at surviving in dry foods, like powdered infant formula, powdered milk, herbal teas, and starches.”

[5] Biden Administration, Press Release “Bill Signing: H.R. 8351” 2022.

[6] Liz Essley Whyte, Kristina Peterson and Jesse Newman, “Baby-Formula Imports to Face Tariffs Again in 2023,” The Wall Street Journal. The Washington Post reported that the tariff rate was an effective rate of 25 percent. Furthermore, the Congressional Research Service found that “Between 2012 and 2021, the United States imported approximately$149 million in infant formula, $29 million (19.4 percent) of which entered duty free. The average effective calculated duty rate on the remaining imports was 25.1 percent.”

[7] Ibid.

[8]Congressional Research Service, Tariffs and the Infant Formula Shortage, 2022. In terms of countries from which the United States did import baby formula products, CRS found “In 2021…Ireland (2.3 million kilograms, $17.2 million) followed by Chile (1.2 million kilograms, $3.3 million) and the Netherlands (0.5 million kilograms, $7.1million). Those three countries represented 93% of all imports (by quantity).”

[9] Following the baby formula shortage, the USDA released new guidance to state agencies on contractual changes required within their “infant rebate formula contracts” related to recalls and shortages. To increase transparency into the bidding process the USDA has created an online website for manufacturers to find and bid on open opportunities.

[10] 89 WIC state agencies, which include 50 state health departments, 33 Indian Tribal Organizations, the District of Columbia, and five territories (Northern Mariana, American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands).

[11] USDA, WIC Eligibility Requirements to Bid on State Agency Infant Formula Contracts.

[12] WIC Healthy Beginnings Act of 2021. Furthermore, as part of the American Rescue Plan of 2021, the USDA was allocated additional funds to modernize and increase participation of eligible beneficiaries in the WIC program. Within this funding, a $50 million grant was set to be divided among WIC state agencies to improve “WIC shopping experience” including the use of online retailers. In March 2023, the Food and Nutrition Service released a proposed rule on online ordering and food delivery for WIC beneficiaries. The agency states that “Online shopping may alleviate some of these issues for WIC participants and has the potential to provide benefits during supply chain disruptions.” The comment period ends on May 5, 2023.

[13] The Consolidated Appropriations Act 2023 (CAA) set out specific reforms related to the oversight of baby formula—including the commissioning of a study to better understand “challenges in supply” as well as “market competition.” The law requires the manufacturers to provide information on recalls to the Department of Health and Human Services. Recently, the FDA released its Immediate National Strategy as required by the CAA, specifically the subsection entitled “The Food and Drug Omnibus Reform Act of 2022.” In terms of the law, the agency is required to publish a long-term strategy, which the FDA anticipates releasing in early 2024.

[14] The CDC posts information on notifiable diseases in monthly reports.

[15] Frank Yiannas, Written Testimony to the Subcommittee on Health Care and Financial Services U.S. House Of Representatives “According to the Centers for Diseases Control and Prevention (CDC), Minnesota and Michigan are the only states that require reporting and the CDC reports that they typically receive reports of only 2 to 4 Cronobacter infections in infants per year. That means that there are likely cases of severe infant illnesses and deaths, although presumably rare, occurring in the United States due to Cronobacter and that those cases remain anonymous, unreported, and invisible to most of the nation.”

[16] Xinjie Song et al. “Cronobacter Species in Powdered Infant Formula and Their Detection Methods” in Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour. 2018 Apr; 38(2): 376–390. Infants that survive an infection can subsequently suffer from “severe neurological impairments…including hydrocephalus, quadriplegia, and developmental delays.” Gallagher and Ball, 1991; Lai, 2001; Gurther et al., 2007; Strydom et al., 2012. Academic studies have shown that to ensure the safety of baby formula requires surveillance of this pathogen.

[17] Xinjie Song et al. “Cronobacter Species in Powdered Infant Formula and Their Detection Methods” in Korean J Food Sci Anim Resour. 2018 Apr; 38(2): 376–390.

[18] FDA Evaluation of Infant Formula Response September 2022, pg. 10.