Insight

November 30, 2017

CFPB and the Tale of Two Directors

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB), the regulatory agency created by the 2010 Dodd-Frank Act has finally made its way into the spotlight. Over the past week, the country watched two people from two different political ideologies simultaneously claim the role of the CFPB’s acting Director. While the debate continues as to who is the real acting Director, and before President Trump nominates and the Senate confirms a new Director, it is useful to take a look at how we got to this point at the CFPB and what it all could mean for consumers and taxpayers going forward.

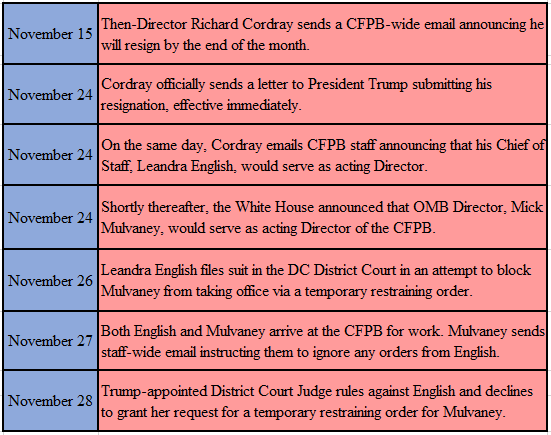

Timeline

Why the confusion?

There are two seemingly conflicting pieces of legislation at issue here. The first, the Dodd-Frank Act, specifically instructs that a Deputy Director appointed by the Director shall “serve as acting Director in the absence or unavailability of the Director.” Since Cordray had no Deputy Director prior to his resignation, his appointment of his Chief of Staff, Leandra English, as Deputy Director would seem to satisfy the requirements of Dodd-Frank and, thus, make her Acting Director.

The Federal Vacancies Reform Act (FVRA), on the other hand, allows the President to “direct a person who serves in an office for which an appointment is required…to perform the functions and duties of the vacant office temporarily in an acting capacity” when “an officer of an Executive agency whose appointment to office is required…dies, resigns, or is otherwise unable to perform the functions and duties of the office.”

Dodd-Frank’s legislative language creates the most confusion. The phrase “absence or unavailability” of the Director typically does not apply to a voluntary resignation situation. Dodd-Frank then does not control who fills this vacancy, and the FVRA applies instead. Therefore, it would follow that Mulvaney would be the rightful acting Director until a new Director is nominated by the White House and confirmed by the Senate.

The Lawsuit

English’s lawsuit against Trump and Mulvaney cites the Dodd-Frank Act twice in her argument for being the rightful acting Director. She first cites the language ordering the Deputy Director to serve as acting Director in the absence or unavailability of the Director. She then cites a previous version of Dodd-Frank, which specifically referenced the FVRA as the mechanism for appointing an acting Director at CFPB, as evidence that Congress demonstrated their intent, by removing this reference to the FVRA, that it not apply.

She goes on to argue that Trump may not appoint Mulvaney because he is currently serving as a White House staffer in his role as OMB Director. Mulvaney’s simultaneous appointment violates the independence of the CFPB, she argues. Further, she claims that she would be “irreparably harmed by the defendants’ actions and threatened actions, and is without an adequate remedy at law.”

Despite her pleas, Judge Timothy Kelly, a recently seated, Trump-appointed judge, denied her request for a temporary restraining order and ruled in favor of the administration by allowing Mulvaney to serve as acting Director of the CFPB. English’s lawyer has indicated that she will appeal the decision.

This appeal could open another can of legal worms. Generally, litigants cannot appeal a denial of a temporary restraining order because it is an interlocutory order, meaning it does not carry sufficient finality for an appeal. However, if granting or denying a temporary restraining order would determine the merits of the case, the decision would be appealable. In this situation, since the case hinges on whether Mulvaney or English is allowed to sit in the Director’s office, the approval or denial of the temporary restraining order could in fact decide the merits of the case. As a result, continued litigation in this case is not out of the question.

What does it all mean?

The CFPB is a rogue, unaccountable agency that has harmed consumers and small businesses with its ever-increasing regulatory burdens. AAF research has found that the agency has levied over $3 billion in regulatory costs during its short, 6-year existence. Further, the CFPB’s rulemaking process is 3.5 times faster than all the other agencies, meaning that it is circumventing the usual notice and comment procedure while it steamrolls its costly rules through the system. Worse, it is not subject to the congressional appropriations and oversight process and instead takes an automatic withdrawal from the Federal Reserve every year to fund its activities. And at the heart of it all is the one Director in whom the entire agency’s powers are vested. That was the intent of the CFPB’s biggest proponents, including Elizabeth Warren, during its creation. But now many are recognizing the danger of having one person control an agency with so much unchecked regulatory (or de-regulatory) ability. In fact, Mulvaney said earlier this week, “I’m just learning about the powers I have as acting director. They would frighten most of you.”

It is important to have a CFPB Director that understands the powers they have and the risks of overregulation. If nothing else, this controversy should highlight the need for reforms to the CFPB. Whether that means turning it into a bipartisan commission structure similar to the Securities and Exchange Commission or, at the very least, subjecting it to congressional appropriations and oversight is for Congress to sort out. But, at least for now, the question of who serves as acting Director is solved. That acting Director supports the administration’s agenda of reducing the regulatory burden, and that’s a win for all consumers.