Insight

March 19, 2024

Changes in Merger Policy Yet To Translate Into Increased Enforcement

Executive Summary

- President Biden’s July 2021 executive order on Promoting Competition in the American Economy cemented competition policy among the top priorities of “Bidenomics,” thus launching a “whole-of government” approach to competition policy.

- This new approach is broadly skeptical of mergers and has shifted enforcement priorities away from a focus on the consumer and toward targeting industrial concentration and corporate dominance to satisfy other political interests.

- Despite the promise of more aggressive merger enforcement by the Federal Trade Commission and the Department of Justice, the agencies’ reforms seem to have translated into lower rates of enforcement action calling into question the efficacy and, by extension, the durability of the agencies’ policy pivot.

Introduction

In July 2021, President Biden issued an executive order (EO) on Promoting Competition in the American Economy. The order ushered in a new “whole-of-government” approach to competition policy and cemented its place among the administration’s top priorities, collectively dubbed “Bidenomics.”

The EO contained a laundry list of directives for federal agencies designed to remedy the alleged harm caused by industrial consolidation and corporate power. The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Justice (DOJ) were among the agencies charged with implementing many of these policy initiatives. In the two-and-a-half years since, the agencies have carried out several policy changes. Many of the policies, however, deviate from the previous 50 years of antitrust and competition enforcement – which focused on the effect market power has on consumers – to fulfill alternative policy goals set by President Biden.

A promise of more aggressive merger enforcement was a core component of the policy changes made at the FTC and DOJ. Despite the promise, data show that the agencies’ reforms seem to have translated into lower rates of enforcement action. This makes it unclear whether the policy transformations will survive beyond the Biden Administration.

President Biden’s Executive Order

President Biden EO on Promoting Competition in the American Economy launched the administration’s “whole-of-government” approach to competition policy and tasked more than a dozen federal agencies with 72 initiatives seeking to remedy “excess market concentration [that] threatens basic economic liberties, democratic accountability, and the welfare of workers, farmers, small businesses, startups, and consumers.”

The order faults industry consolidation for weakened competition that “den[ies] Americans the benefits of an open economy and widening racial, income, and wealth inequality,” and adds that “federal government inaction has contributed to these problems.”

The FTC and DOJ were tasked with several initiatives, the most notable being directives to take a tough stance on mergers and acquisitions. The EO instructs the agencies, among other things, to “review the horizontal and vertical merger guidelines and consider whether to revise those guidelines.” The order specifies that the acquisition of nascent competitors, serial mergers, and the ability of the agencies to challenge prior bad mergers should be prioritized. Several other dictates related to competition were assigned to the agencies.

The EO also established the White House Competition Council, headed by the Director of the National Economic Council. The purpose of this new council was to oversee and coordinate the implementation of all the initiatives outlined. Several new policy initiatives were announced following the council meetings, including plans to combat junk fees, a “Strike Force” to “crack down on unfair and illegal pricing,” and the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau’s plan to cap credit card late fees. The most recent meeting of the council, its sixth such meeting, took place in March 2024.

FTC and DOJ Response to the Executive Order

Prior to President Biden issuing the executive order, the FTC and DOJ announced a temporary suspension of early termination in February 2021. Early termination is a long-standing practice allowing mergers and acquisitions that posed no competitive concerns to close quickly. Over most of the past decade, between 73 and 81 percent of early termination requests were granted by the agencies, but with the suspension in effect for the entirety of fiscal year (FY) 2022, the agencies granted just five out of 1,345 requests, a rate of 0.4 percent. More than three years after the announcement, the temporary suspension is still in place with no timetable for its reinstatement.

Heeding President Biden’s call to action, the FTC and DOJ announced several other policy changes with respect to merger oversight and enforcement.

In September 2021, the FTC, without parallel action from the DOJ and a split 3–2 partisan vote among commissioners, withdrew support for the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines. In the announcement, the FTC asserted that the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines included “unsound economic theories that are unsupported by the law or market realities” and signaled its intention to “work with the DOJ to update the merger guidance.”

Soon after, in December 2021, the DOJ’s Antitrust Division announced that it was seeking public comments on bank merger analysis and whether to revise the 1995 Bank Merger Competitive Review Guidelines. Preempting any final changes to the review process, Assistant Attorney General Jonathan Kanter announced plans to broaden the existing framework used by the agency. Furthermore, Kanter reaffirmed the agency’s commitment to challenging bank mergers using the antitrust laws, even if the merger was approved by the primary banking regulators.

A month later, in January 2022, the FTC and DOJ announced their intention to revise the existing merger guidelines. After a seven-month process, the agencies published draft Merger Guidelines intended to replace the 2010 Horizontal Merger Guidelines and the 2020 Vertical Merger Guidelines. While the Merger Guidelines do not have the force of law, they provide the business community, antitrust practitioners, and the courts with insights into how the agencies evaluate merger and acquisition compliance with federal antitrust law. Following a public comment period in which the agencies received over 30,000 comments, the final version of the Merger Guidelines was published in December 2023. Effectively, the analytical framework outlined in the Merger Guidelines will deem more mergers to be illegal. Moreover, the Merger Guidelines were broadly skeptical of merger efficiencies as a defense of transactions.

Amid the revisions to the Merger Guidelines, the FTC and DOJ proposed changes to the rules governing the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act (HSR) in June 2023. The HSR, enacted in 1976, established the federal premerger notification program, which requires businesses planning a merger or acquisition of a certain value to notify the antitrust agencies before consummating the transaction. The proposed changes, when finalized, would be the first overhaul of the rules in 45 years. The FTC estimated that the changes will quadruple the time needed to prepare the required paperwork and cost $350 million in additional labor hours.

These explicit policy changes have reshaped the merger and acquisition landscape, making it a more expensive and riskier proposition for businesses. At an event hosted by the American Action Forum, former FTC Commissioner Noah Phillips equated these actions to a “tax,” stating that there is a “desire to add costs across the board.”

A telling sign that the FTC, specifically, is unconcerned with raising costs – both financially and in terms of regulatory risk – was evident in a change to the agency’s mission statement published in its Strategic Plan for Fiscal Years 2022–2026. For decades, the agency’s mission statement included the phrase “without unduly burdening legitimate business activity.” That phrase was removed in the latest document. Axing the phrase signaled to the business community that the agency will act aggressively without concern for cost to economic activity.

Sewed among the explicit policy changes were statements made by agency leaders promising changes in tactics with respect to merger enforcement. One such example involved FTC Chair Lina Khan, Assistant Attorney General of the Antitrust Division Jonathan Kanter, and FTC Competition Director Holly Vedova voicing skepticism about the practice of business divestiture offers – an asset, or even entire business units, sold to restore or maintain competition in a market affected by a merger – as remedies in merger cases and signaled that the agencies may consider abandoning the practice entirely. The move ignored the findings of an FTC retrospective study analyzing merger remedies from 2006–2012 that found that “all of the divestitures involving ongoing business succeeded,” and that “80% of the…[divestiture] orders maintained or restored competition.”

Commissioner Phillips discussed how political marketing tactics from the agencies work in conjunction with hard changes in policy to advance their agenda. He noted that “agencies can move the needle in terms of the conduct of actors just by saying things loudly. There is a lot of statements by the agencies, but also there is a lot of coverage and a lot of hype and that has some value in drawing attention to what is going on.” Phillips expressed concern that this type of soft policymaking is a “deliberate strategy to effectuate through a mechanism that isn’t subject to due process, it isn’t subject to courts, it doesn’t go through notice and comment or all of these checks and balances we have to mediate how law enforcement and how regulation are effectuated in our society.”

The mix of rhetoric and direct policy changes have ushered in an enforcement regime determined to crack down on and even stop merger activity.

Merger Enforcement Across Administrations

The policy changes implemented by the FTC and DOJ and accompanying rhetoric critical of mergers left many to expect an increased number of in-depth merger investigations and a heightened rate of enforcement compared to prior administrations. Data from the agencies’ Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Report, however, showed that Second Requests and merger enforcement has, thus far, declined during the Biden Administration.

For mergers that raise sufficient competitive concerns during the initial investigation, the agency can issue a Request for Additional Information, known as a Second Request. The Second Request requires that both parties to the merger provide the agency with more information and extend the mandatory waiting period by an additional 30 days before the merger can be consummated.

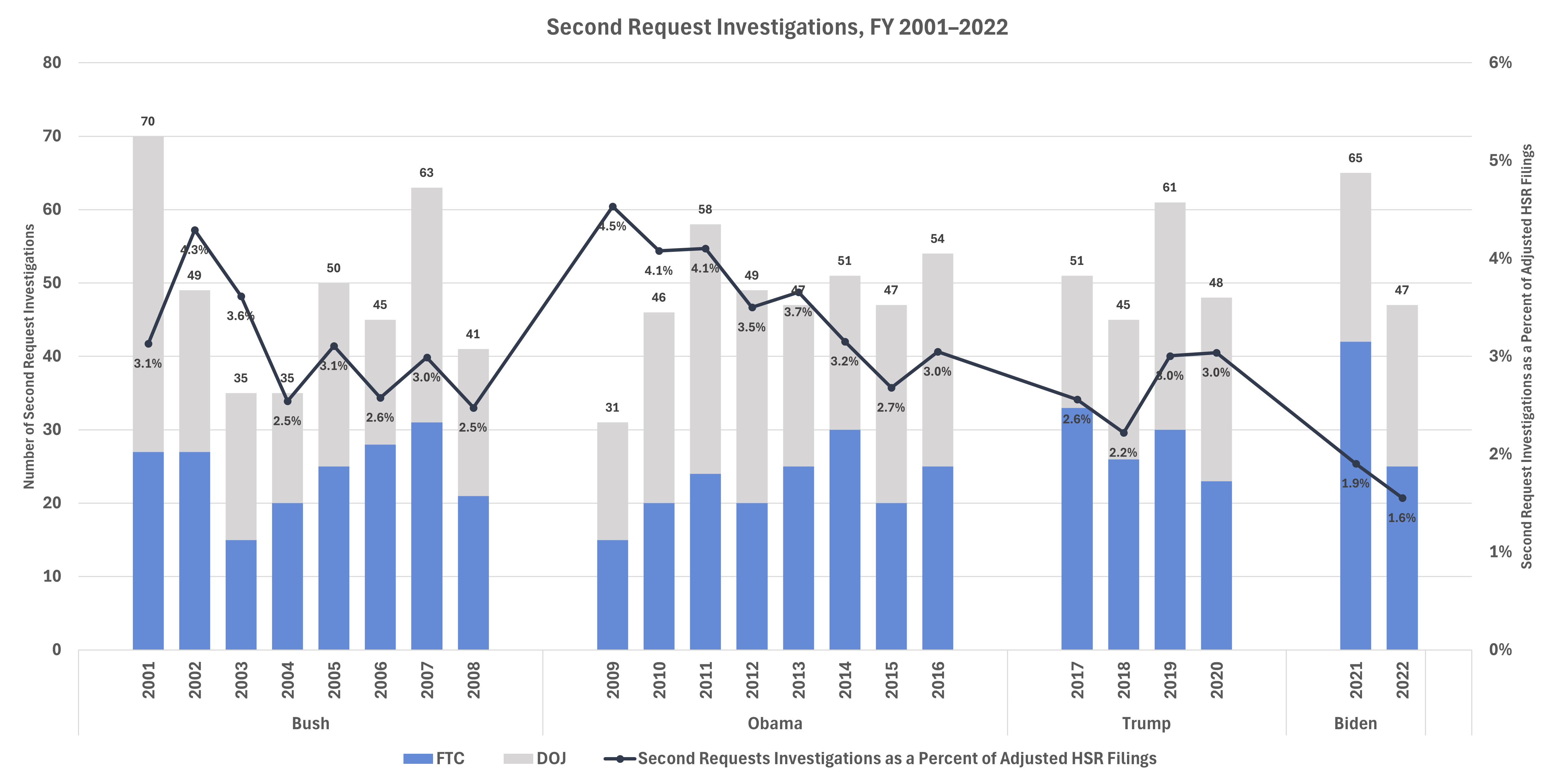

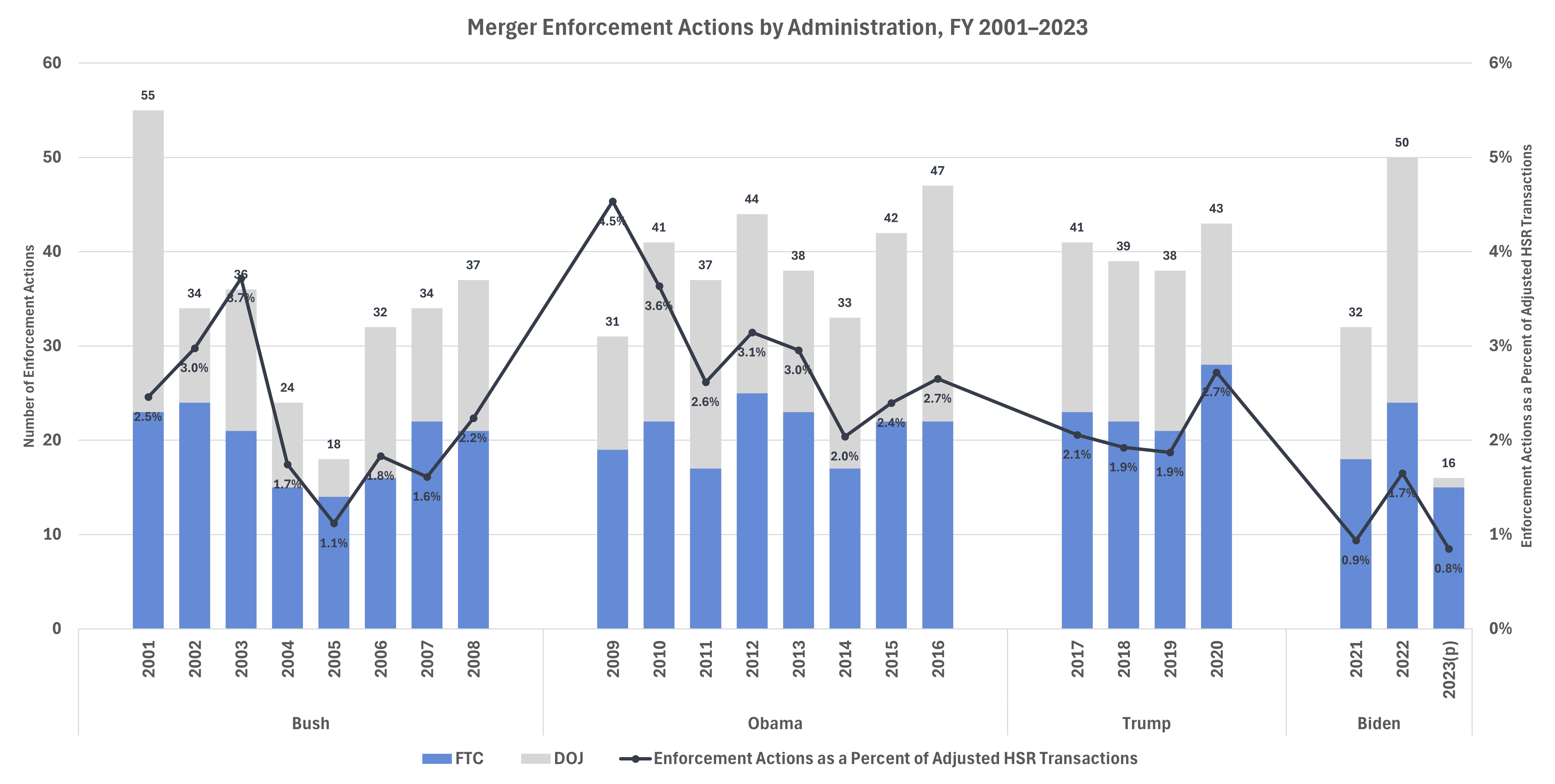

Figure 1 shows the number of Second Request investigations initiated by the agencies and as a share of adjusted HSR filings. Summary data across administrations are shown in Table 1.

Figure 1

Table 1

*Data for the Biden Administration include FYs 2021 and 2022. FY 2023 data are not yet available.

The rate of Second Requests has slowed to under 2 percent during the first two years of the Biden Administration compared to an average of 3.1 percent over the collective three prior administrations.

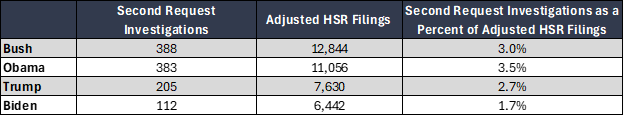

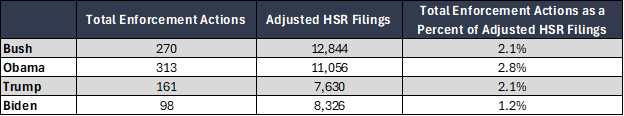

The rate of merger enforcement actions – either an administrative or judicial process – has followed a similar pattern. Figure 2 shows the number of enforcement actions and the rate of enforcement between FYs 2001–2023. The rate of enforcement is calculated as the number of enforcement actions as a percent of adjusted HSR filings. Summary data across administrations are shown in Table 2.

Figure 2

*Source: Data for FYs 2001–2022 are from Hart-Scott-Rodino Annual Report; FY 2023 data from preliminary HSR data, press releases, and FTC letter to Representative Thomas P. Tiffany (R-WI).

Table 2

The three prior administrations had an enforcement rate above 2 percent, while the enforcement rate so far in the Biden Administration has dropped to 1.2 percent. The enforcement rate in FYs 2021–2023 was among the lowest since 2005.

More salient, at least concerning media attention, is the agencies’ court record. Notable mergers challenged by the FTC under Chair Khan’s direction included Microsoft’s acquisition of Activision Blizzard, Meta’s acquisition of Within, and Illumina’s acquisition of Grail. The FTC lost all these litigated cases (Illumina eventually divested Grail after a court decision that determined the FTC applied the wrong legal standard but offered enough evidence to continue to try to block the deal).

The heightened rhetoric and expanded scope of mergers the antitrust enforcement agencies consider illegal has yet to translate into increased or successful merger enforcement. It is possible that this new approach will be short-lived, as a new administration could return enforcement focus to that of measuring the effects mergers have on competition and market power and the potential harm posed to consumers.

Uncertainty as an Enforcement Tool

Commissioner Phillips explained that one way the Biden Administration can impose a merger “tax” is to create uncertainty. The agencies’ skepticism toward mergers, coupled with new policy initiatives, has sowed uncertainty in the business community. This uncertainty itself has acted as a successful deterrent to slow merger activity.

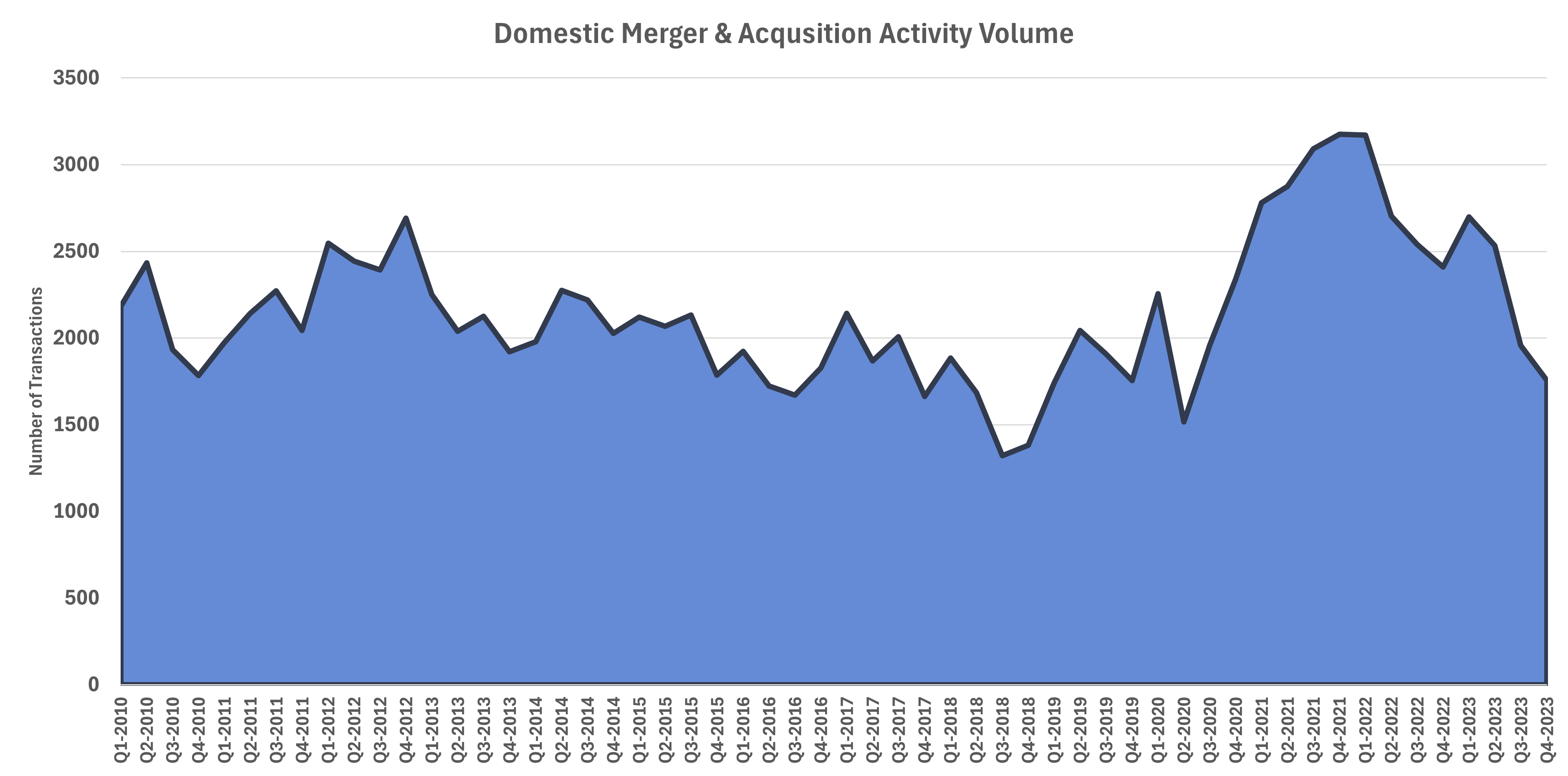

Data from White & Case showed that deal volume plummeted by 45 percent between Q4-2021 and Q4-2023.

Figure 3

* Source: White & Case: Target Location: USA, Bidder Location: USA, Sector: All Sectors

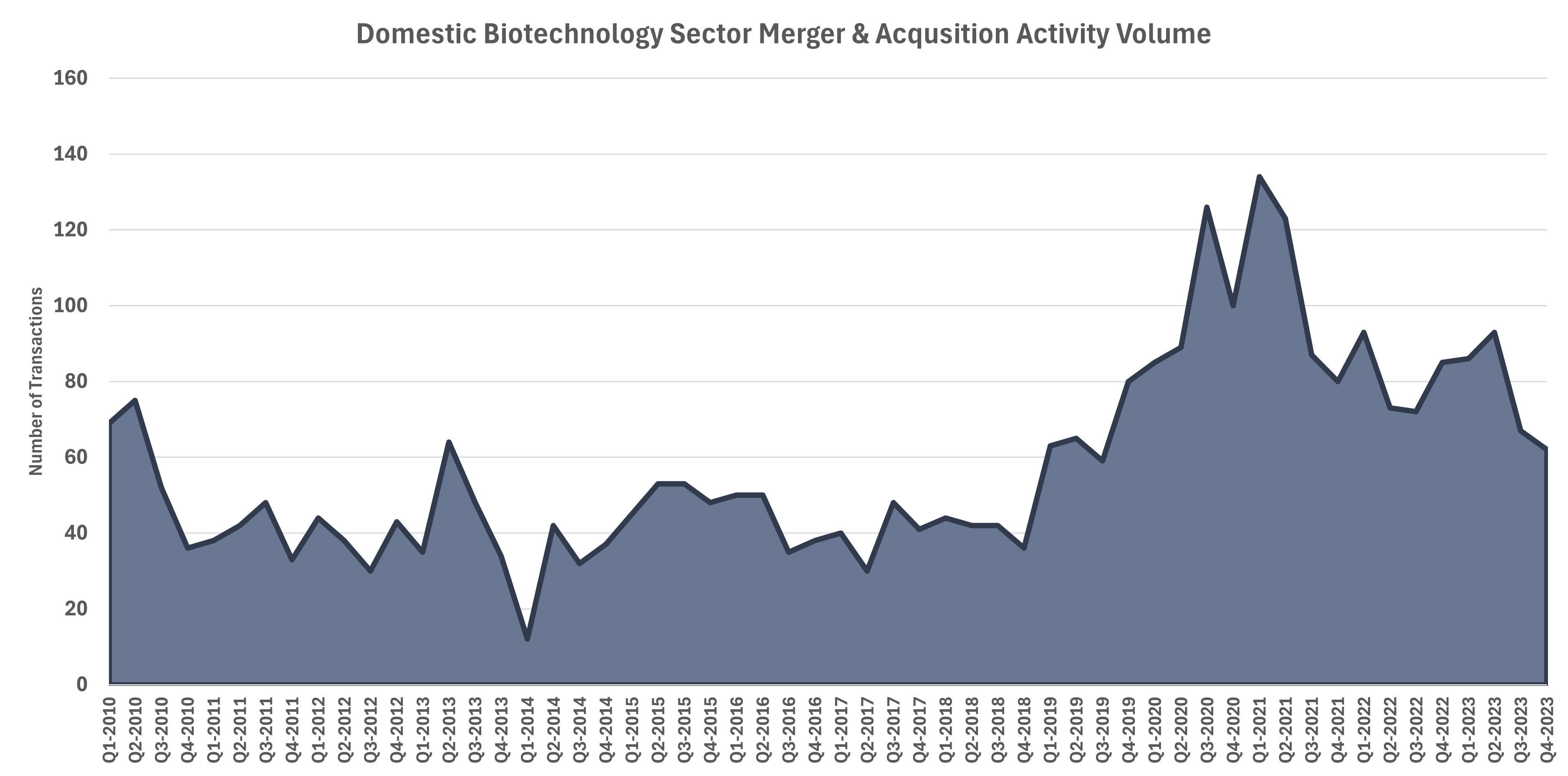

Dealmaking in the biotechnology sector has slowed dramatically since volume peaked in the first quarter of 2021, down 54 percent.

Figure 4

* Source: White & Case: Target Location: USA, Bidder Location: USA, Sector: Biotechnology

The Biotechnology Innovation Organization, Illinois Manufacturers Association, Chicagoland Chamber of Commerce, and Illinois Biotechnology Innovation Organization filed an amicus brief in the FTC’s case challenging Amgen’s merger with Horizon Therapeutics. In the brief, the groups explain that the biopharmaceutical industry, an end-user of products developed by the biotechnology sector, “depends on dynamic merger and acquisition activity to allocate risk, the raise and deploy capital, to develop and test new drugs, to obtain regulatory approval, and to produce approved drugs in sufficient quantities to meet consumer demand in the U.S. and throughout the world.”

The explicit and verbal changes to policy made by the agencies threaten a functioning merger market and stifle legitimate business activity that pose no identifiable threat to competition or harm consumers.

Conclusion

President Biden’s EO on Promoting Competition in the American Economy cemented competition policy among the top priorities of “Bidenomics.” As a result, the FTC and DOJ have shifted merger enforcement priorities away from a focus on market power and its effect on consumers and toward a “whole-of-government” approach to merger enforcement designed to remedy the alleged harms of industrial concentration and corporate dominance.

More than two-and-a-half years into this experiment, new policies and harsh rhetoric have failed to translate to tougher merger enforcement and have led to a series of losses in court. It is possible that this new approach will be short-lived and a change in administration could return the agency to its previous mission of protecting consumers from mergers that result in increased market power.