Insight

February 3, 2022

Debt Management in a Time of Quantitative Tightening

Executive Summary

- The U.S. Treasury market is the largest and deepest of any single issuer in the world, while U.S. Treasury securities are an essential benchmark in global financial markets.

- The market faces some uncertainty, as the Treasury’s largest customer of late, the Federal Reserve, ceases to purchase and ultimately reduces its Treasury holdings.

- As Treasury’s debt managers grapple with this challenge, the quarterly refunding process will serve as a crucial forum for ensuring regular and predictable debt issuances.

Introduction

Federal finance is in somewhat of a delicate dance, as the Treasury Department must adjust its debt management operations while its largest customer, the U.S. Federal Reserve, embarks on tightening monetary policy. The central bank has signaled an intention to reduce its holdings of Treasury securities as it shifts away from the extraordinarily accommodative monetary policy of the recent past, and to a large extent, the last decade. This has significant implications for financial management as well as fiscal policy. To assist the Treasury in gauging the market’s appetite for federal debt, the Treasury’s Office of Debt Management convenes the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee, or TBAC, on a quarterly basis as part of what is known as the quarterly refunding process. This process provides a forum for the regular exchange of views and information among Treasury officials and the key participants in the market for buying and selling of Treasury debt. Given the unique tensions confronting Treasury debt management, this week’s quarterly refunding announcement offers an opportune moment to assess the institutional outlook for federal finance.

The Quarterly Refunding Process

The U.S. Treasury market is the largest and deepest market of any single issuer in the world. U.S. Treasury securities are viewed as essentially riskless and serve as a fundamental benchmark in global financial markets. The engine room for the world’s deepest government securities market is the Treasury’s Office of Debt Management, helmed by a career federal official. Ultimately reporting to the assistant secretary for Federal Finance, and housed within Treasury’s Office of Domestic Finance, the Office of Debt Management is charged with formulating policy for the federal government’s borrowing needs.

The essential mission for the office is to finance the federal government’s obligations at the lowest cost over time. This mission is challenged by necessary uncertainties in federal cash flows, federal borrowing needs, Treasury markets, and the macroeconomy in general. That the Treasury seeks to manage costs over time is also a key consideration, and necessarily depends on the outlook for federal finance. For example, short-term interest rates are generally lower than long-term rates, perhaps suggesting that a cost-conscience Treasury would generally prefer financing federal obligations with short-term debt, such as Treasury bills, which have maturities of less than a year. But financing the federal government through short-term bills comes with risks over time. A 52-week Treasury bill may have a lower interest rate than a 30-year bond, but depending on future interest rates, it may be cheaper for the federal government to finance an obligation with a 30-year bond than 30 successive 1-year securities, particularly given the profound uncertainty of interest rates over a 30-year period. As an analogy, consider a homebuyer choosing between a 30-year fixed mortgage or a shorter-term adjustable-rate mortgage (ARM). The buyer may be better off today with an ARM but may be sorry when interest rates rise.

Managing this balance is a key task of the Office of Debt Management. For decades, Treasury has adhered to the principle that debt issuances should be “regular and predictable.” In practice, this principle animates the Treasury’s regular auction schedule, deliberate process for debt management policy changes, and clear communication to market participants. The quarterly refunding process is critical to those activities.

Quarterly Refunding

Four times a year, Treasury debt managers engage in a formal process to refine federal debt management policy known as the Treasury Quarterly Refunding Process. As part of this process, Treasury solicits the views of its most significant direct customers – the primary dealers. Primary dealers are major financial institutions that directly buy Treasury securities from the New York Federal Reserve Bank, which serves as the U.S. Treasury Department’s, and indeed, the federal government’s fiscal agent. There are presently 24 primary dealers that can, and must, participate in direct purchases of Treasury securities at auction. More formally, the Treasury convenes the Treasury Borrowing Advisory Committee (TBAC) to advise on market conditions and respond to Treasury’s views and intentions with respect to debt management. The TBAC is a federally chartered advisory committee to the Treasury Department. While the charter allows for up to 20 members, present membership is composed of 15 senior representatives of primary dealers, institutional investors, and other major participants in Treasury markets.

As part of this process, the TBAC meets with key Treasury officials once per quarter to exchange views on the Treasury markets and the expected course of federal borrowing. While the meeting itself is private to protect the sensitivity of the discussion, sanitized minutes of the meeting are published the following day. In addition to serving as an advisory function, the quarterly refunding process is also the forum in which Treasury makes public key changes in its debt management policies and outlook, again in keeping with the principle of regularity and predictability in Treasury debt management.

From a review of the most recent formal statement from the TBAC to the Treasury, and the Treasury’s policy statement, it is clear that federal finance is facing key uncertainties as the Treasury’s largest customer, the Federal Reserve, prepares to reduce its Treasury holdings in the coming months.

The Federal Reserve: Treasury’s Best Customer

Since the global financial crisis, monetary and fiscal policy have increasingly overlapped. Through a number of operations, broadly characterized as “quantitative easing,” the Federal Reserve significantly expanded direct purchases of federal securities to support low interest rates and in turn buttress the U.S. economy in the face of the Great Recession and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic. Fiscal policy similarly expanded, along with higher borrowing needs. Indeed, between the end of February 2020 and the end of December 2021, the U.S. marketable debt held by the public increased by over $5.6 trillion. For budget watchers, this is an alarming increase in debt. Yet it also demonstrates the extraordinary borrowing power of the United States, and the appetite for U.S. Treasury securities in global markets.

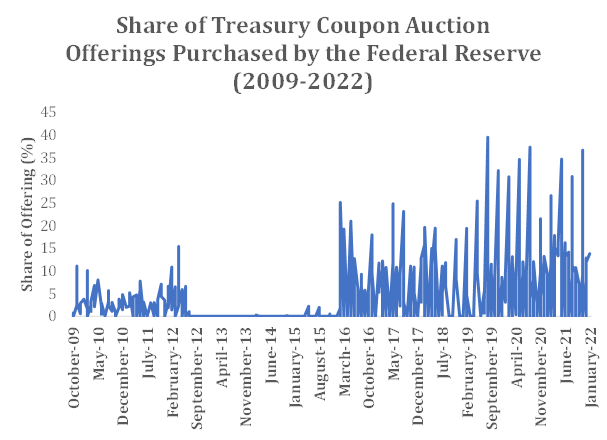

It is important to note, however, that the Treasury had help from the statutorily independent Federal Reserve. While the U.S. debt grew by over $5.6 trillion, Treasury holdings by the Federal Reserve grew by $3.2 trillion. As a share of coupon auction offerings (Treasury auctions for notes and bonds), the Federal Reserve has purchased as much as 40 percent of the securities on offer – more than twice as high a share as was ever purchased in the extraordinary Federal Reserve actions during the Great Recession.

This dynamic is consequential for fiscal policy, as well. The Federal Reserve remits its net income to the Treasury, which necessarily includes interest it earns on its significant Treasury portfolio. In FY2021, the Federal Reserve remits over $100 billion to the Treasury, a significant share of which is essentially recycled interest payments. For Treasury markets, the loss of this big buyer is a challenge for market participants, such as those represented by the TBAC and Treasury debt managers, to navigate.

As the labor market has recovered rapidly from the brief recession of 2020, however, inflationary pressures have outpaced nominal wage growth, precipitating a rapid shift in monetary policy. The Federal Reserve is widely expected to increase interest rates at its March meeting and begin to gradually reduce its Treasury holdings later this year. In its presentation to Treasury this week, the TBAC estimated that the runoff in the Federal Reserve’s Treasury holdings would create a need to for the Treasury to find new buyers for $1.6 trillion in new debt securities over the next three years.

A key example of the “give and take” of the quarterly refunding process is reflected in the TBAC’s report to the Secretary of the Treasury, which substantially responds to Treasury’s policy statements and borrowing estimates, among other communications. It’s noteworthy that in this week’s report the TBAC advised the Treasury to adjust its planned reductions in certain debt issuances given the prospective reduction in demand from the Federal Reserve and in light of observed market conditions.

Conclusion

The U.S. central bank is embarking on an epochal shift in monetary policy, which has been largely accommodative for more than a decade. That shift is occurring in a relatively rapid fashion that has roiled markets and is also posing challenges to public finance. The Federal Reserve became the Treasury Department’s best customer, right at the time “business” was booming. As the Federal Reserve unwinds its portfolio, the quarterly refunding process will feature prominently in ensuring that U.S. Treasury markets remain attractive to investors, while financing federal obligations as efficiently as possible.