Insight

July 18, 2023

Does the 340B Drug Pricing Program Encourage High-cost Prescriptions? A Case Study of Preventative HIV Treatments

Executive Summary

- The 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B Program) may incentivize hospitals and other covered entities to purchase higher-cost drugs rather than lower-cost generic medicines when competition is fierce; this incentive likely applies to the purchase of preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) antiretroviral prescriptions used to treat HIV.

- For Medicare and other insurers, the preference of covered entities for higher-cost PrEP drugs in the 340B Program could put significant pressure on premiums, patient cost-sharing, and public budgets.

- Congressional action on the 340B Program would be necessary to ensure that incentives for higher-cost drugs do not undermine broader U.S. public health initiatives or increase costs to federal programs that treat HIV patients.

Introduction

The 340B Drug Pricing Program (340B Program) may incentivize hospitals to purchase higher-cost drugs rather than lower-cost generic medicines, particularly when such medication is at the end of its patent period and new brand or generic products are coming to market. In light of the federal government’s ongoing efforts to prevent human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infections with now widely used prophylactic medications, this insight examines whether covered entities favor higher-cost preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) antiretroviral prescriptions over lower-cost generics in the 340B Program.

Whether or not a preference for branded drugs over generics affects an individual patient’s cost, covered entities favoring a higher-cost drug put significant pressure on Medicare and Medicaid spending, as well as insurance premiums. Of note, this incentive seems especially pronounced with respect to preventative HIV medications dispensed by 340B-eligible clinics and safety-net providers.

The 340B Program created in 1992 to “stretch scarce federal resources”[1] by allowing covered entities, such as hospitals, to purchase physician-administered and out-patient drugs at a discount (typically 25 percent or more) from those manufacturers participating in the Medicaid program. The drug is then reimbursed by an insured patient’s health plan at a higher price. In turn, the covered entity is expected to use the gains from the commercial sale of the drug to provide otherwise uncompensated care to underinsured or uninsured patients. For 340B Program covered entities, there is an incentive for covered entities to prefer the high-cost branded products over low-cost generics, which cannot offer large rebates or additional reimbursement for the dispensing of their product.

Covered entities that can dispense PrEP and other HIV (human immunodeficiency virus) medications through the 340B Program include certain hospitals, Ryan White Clinics and State AIDS Drug Assistance programs, Medicare/Medicaid Disproportionate Share Hospitals, children’s hospitals, and other safety net providers. Of note, 340B covered entities are prohibited by statute from generating profits on 340B prescriptions dispensed to a Medicaid beneficiary to prevent duplicating discounts manufacturers offer separately to Medicaid.[2] Furthermore, while there is some evidence that overall generic prescribing rates between 340B and non-340B entities are similar; in particular drug classes or situations like that of PrEP where manufacturers are approaching the end of a patent period, divergences in dispensing emerge.[3]

This insight focuses on the degree to which covered entities in the 340B Program are incentivized to purchase the more expensive, branded HIV drugs. Potentially, the program is unnecessarily encouraging the purchase of higher-priced prescriptions, which may inflate the costs of Medicare, Medicaid, private insurers, employers, patients, and ultimately taxpayers, which fund most PrEP interventions.[4]

Congressional action on the 340B Program would be necessary to ensure that incentives for covered entities to prefer higher-cost drugs are not undermining broader U.S. public health initiatives or increasing costs to federal programs to treat HIV patients. The American Action Forum has extensively covered the 340B Drug Pricing Program and identified the many issues, including recent legal challenges, that arise from its lack of statutory purpose.

Federal Funding of HIV/AIDS Care

HIV/AIDS continues to be a significant public health challenge as more than 1.1 million Americans are living with HIV, and over 700,000 Americans have lost their lives to HIV since 1981.[5] While nearly half of HIV health care is financed by Medicaid, Medicare accounted for approximately 40 percent of total federal spending on HIV in the United States. Recipients of HIV health care through Medicare are typically younger than 65, male, Black or Hispanic, and qualified under Medicare based on their disability status.[6] More than half a million people with HIV-more than half of all people with diagnosed HIV-are treated by Ryan White Clinics, an entity that participates in the 340B Program, allowing them the opportunity to generate 340B-related revenue on HIV medications.

In President Trump’s 2019 State of the Union address, he promised that his budget would “ask Democrats and Republicans to make the needed commitment to eliminate the HIV epidemic in the United States within 10 years.” Following this request, the Ending the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. (EHE) initiative was announced with the aim to reduce new HIV infections by 75 percent in 2025 and by at least 90 percent in 2030. Most recently, President Biden’s fiscal year 2024 budget requested $850 million to fund the EHE.[7] Yet several challenges remain as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recently estimated that new HIV infections fell only 8 percent from 2015–2019.

Within the Department of Health and Human Services fiscal year 2024 budget, the agency proposed “a mandatory national program that invests $9.8 billion over 10 years to provide a financing and delivery system to ensure everyone has access to pre-exposure prophylaxis, also known as PrEP, via community providers. The program would include PrEP drugs, associated lab services, and ancillary services to support PrEP uptake and consistent use by clients.” This mandated program is projected to save $10.2 billion over 10 years. This program may increase PrEP uptake by reducing unspecified barriers for potential beneficiaries. Yet questions around the preference for 340B entities to use brand name PrEP medications over low-cost generics remains.

Understanding Preexposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) Treatment

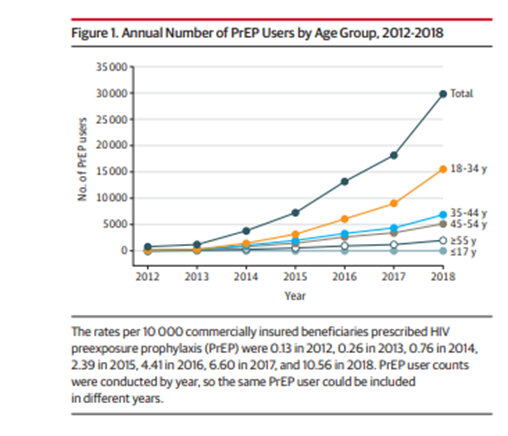

Since 2012, the dispensing of prophylactic HIV medications has increased dramatically. A recent study found that the average number of PrEP medications dispensed in 2018 was 10.56 per 10,000 patients as compared to .13 per 10,000 patients in 2012. Although the study had data limitations (Medicaid was excluded), the chart below shows the dramatic uptake in commercial coverage of PrEP medications.

PrEP medications aim to prevent HIV infection altogether and are generally prescribed to high-risk patients.[9] Nearly 20 years ago, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a pill-based preventative medication called Truvada, manufactured by Gilead Sciences. In 2012, Truvada was approved by the FDA as a PrEP medication. That was followed by Descovy in 2015, produced by the same company. Both drugs contain two anti-HIV medications to prevent at-risk individuals from contracting the virus.[10] Descovy is prescribed specifically for at-risk sexually active men and transgender women. In 2021, the FDA also approved a long-acting injectable administered every two months for at-risk patients.

In anticipation of Truvada’s patent expiration in September 2020, Gilead Sciences brought Descovy to market.[11] An academic study found that “as of October 2020, internal data from Gilead Sciences reported that 46 percent of PrEP users have switched to Descovy.” Moreover, the study acknowledged that the number of individuals that switched to Descovy could be larger as many patients switched from Truvada to Descovy (rather than the generic version of Truvada) based on their physician’s recommendations.[12]

Teva Pharmaceuticals Industries Ltd. manufactures the generic version of Truvada – Emtricitabine and Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate tablets (generic Truvada). For generic Truvada, the monthly cost for patients is estimated between $30–$60, while the monthly list price of Descovy is $2,159.

Perverse Incentives in the 340B Program

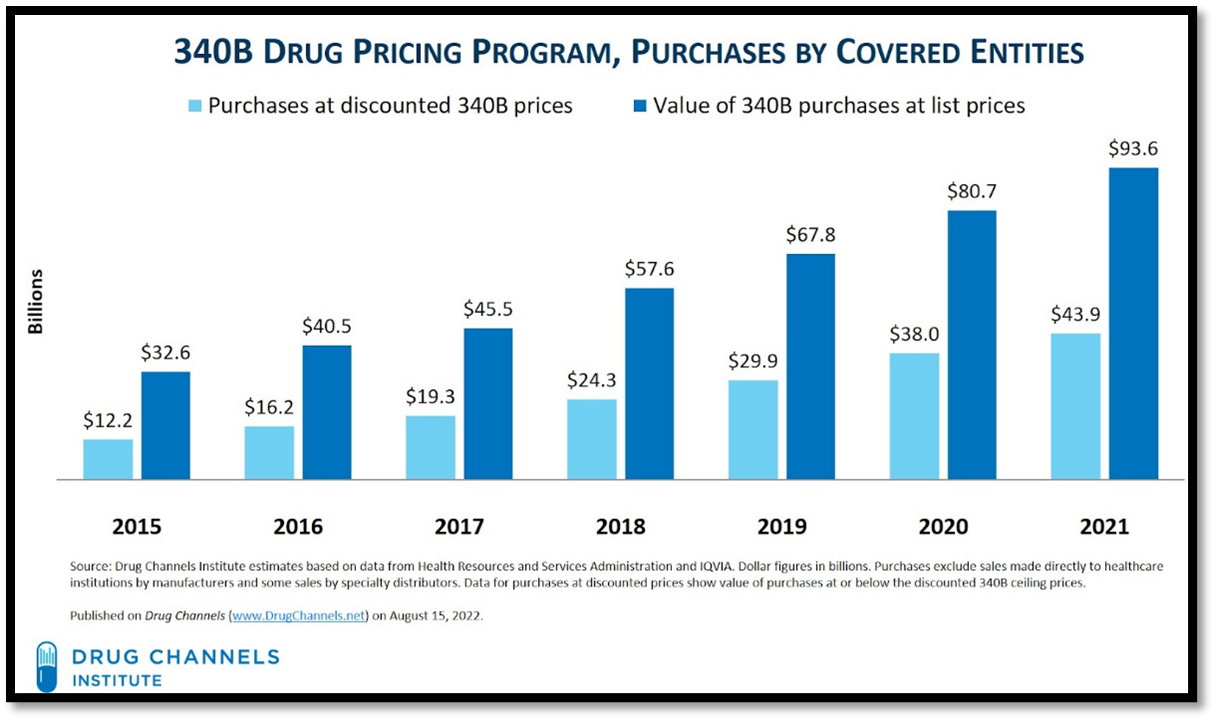

The 340B Program may incentivize hospitals and other covered entities to purchase highly rebated products to generate the greatest spread from the sale of the drug. See the chart from Drug Channels below, which illustrates typical yearly difference between the purchase made by the covered entity at the discount price as compared to the value of the drugs purchased at the list price.

A further study from Drug Channels found that in 2021 “the difference between list prices and discounted 340B purchases also grew, to $49.7 billion.” In that same year, NBC News reported that one estimate on the 340B Program spread for “a single prescription for Truvada or Descovy amounts to about $1,200 to $1,600 monthly, or $14,400 to $19,200 annually.” For hospitals, dispensing the branded product generates significant profits as compared to lower cost generics.

Of course, since the presumed purpose of the 340B Program was for covered entities to use manufacturer discounts to provide indigent care, the fact that there is a spread is not necessarily a problem. The problem arises when covered entities are incentivized to put patients on unnecessarily high-cost drugs that drain resources from public and private health care payers. Since the 340B Program does not mandate a minimum level of charitable care, there is no guarantee that covered entities are providing adequate resources for the program’s intended population.

Covered entities in the 340B program have demonstrated a clear preference for the higher-priced brand PrEP products. That phenomenon is somewhat unique among other 340B drug classes since the manufacturer actively provided an assistance program over and above the mandatory 340B Program to cash-strapped health clinics serving uninsured patients, allowing them to generate additional revenue from prescriptions. While this is good for patients and clinics, it arguably promotes higher-cost treatments over the long-term. A recent Johns Hopkins University paper highlighted that “Gilead’s Advancing Access program for uninsured individuals also offered an opportunity for providers to generate revenue. 340B providers have been able to purchase the drug at the 340B discounted price and then seek reimbursement from Gilead’s Advancing Access program at a much higher usual and customary rate.” This is not surprising as large manufacturers have the financial resources to incentivize hospitals to purchase their products as compared to generic manufacturers.

The problem with the 340B Program is not that covered entities benefit financially by dispensing HIV medications, it is that a federal program incentivizes them to favor more expensive treatments, raising costs for the rest of the health care system. In the case of PrEP, the underlying 340B incentive is magnified due to an additional manufacturer reimbursement. But 340B has the potential to disrupt appropriate generic prescribing in similar drug classes. Of course, not employing substantial savings from generic use where appropriate results in substantial knock-on costs to patients and government health programs.

Conclusion

Congressional action on the 340B Program would be necessary to ensure that perverse incentives to favor higher-cost drugs are not undermining broader U.S. public health initiatives. When the program’s covered entities have a substantial incentive to avoid otherwise appropriate generics, particularly in specific drug class circumstances like that of PrEP treatments, payers for HIV treatments and services, such as Medicare, are likely to face unnecessarily inflated costs.

[1] The Commonwealth Fund, “340B Drug Discount Program: Why More Transparency Will Help Low-Income Communities” 2018.

[2] According to the Heath Resources & Services Administration (HRSA) “42 USC 256b (a) (5) (A) (i) prohibits duplicate discounts; that is, manufacturers are not required to provide a discounted 340B price and a Medicaid drug rebate for the same drug. Covered entities must have mechanisms in place to prevent duplicate discounts.” For information, please see MEDPAC’s 2018 report “The 340B Drug Pricing Program and Medicaid Drug Rebate Program: How They Interact.”

[3] Amelia M. Bond, Emma B. Dean, and Sunita M. Desai “The Role Of Financial Incentives In Biosimilar Uptake In Medicare: Evidence From The 340B Program” Health Affairs Vol. 42, No. 5. The authors found that “Using a regression discontinuity design and two high-volume biologics with biosimilar competitors, filgrastim and infliximab, we estimated that 340B program eligibility was associated with a 22.9-percentage-point reduction in biosimilar adoption. In addition, 340B program eligibility was associated with 13.3 more biologic administrations annually per hospital and $17,919 more biologic revenue per hospital. Our findings suggest that the program inhibited biosimilar uptake, possibly as a result of financial incentives making reference drugs more profitable than biosimilar medications.”

[4] According to HIV.gov “The U.S. government investment in the domestic response to HIV has risen to more than $28 billion per year, including discretionary spending as well as mandatory spending for Medicare, Medicaid, Social Security benefits, and other mandatory spending.”

[5] Amanda Honeycutt, Sophia D’Angelo, Adam Vincent and Laurel Bates “U.S. PrEP Cost Analysis” RTI International 2022.

[6] Lindsey Dawson Follow, Jennifer Kates, Tatyana Roberts, Juliette Cubanski, Tricia Neuman, and Anthony Damico “Medicare and People with HIV” Kaiser Family Foundation, March 2023.

[8] Hyun Jin Song; Patrick Squires; Debbie Wilson et al. “Trends in HIV Preexposure Prophylaxis Prescribing in the United States, 2012-2018” JAMA. 2020;324(4):395-397.

[9] Typically, PrEP is a pill-based combination medication of two antiretrovirals that are prescribed as a preventive treatment for healthy people at risk of contracting HIV. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved PrEP as a pill-based medication in 2012 and an injectable therapy in 2021. A generic, pill-based PrEP medication was approved in 2020. Studies have shown that PrEP provided an estimated 99 percent risk reduction of contracting HIV through sex and a 74 percent risk reduction through intravenous drug use.

[10] According to HIV.gov “Truvada is for all people at risk for HIV through sex or injection drug use. Generic products are also available. Descovy is for sexually active men and transgender women at risk of getting HIV. Descovy is not for people assigned female at birth who are at risk for HIV through receptive vaginal sex. A long-acting injectable form of PrEP, Apretude has also been approved by the FDA. It is for people at risk for HIV through sex who weigh at least 77 pounds. It is administered by a health care provider every two months instead of daily oral pills.”

[11] In February 2023, Gilead Sciences noted that Descovy sales in the fourth quarter of 2022 as compared to the fourth quarter in 2021 increased 13 percent to $537 million. A recent lawsuit between Gilead Sciences and generic manufacturers agreed that a generic to Descovy can come to market in 2031. Moving patents from a branded product nearer to patent expiration to a drug with a longer patent life is known as “evergreening.” Furthermore, drug manufacturers may offer copay assistance programs for patients to receive their branded products. Generic manufacturers cannot offer large rebates or additional monies for patients to purchase their lower cost product.

[12] Alexa B. D’Angelo, Drew A. Westmoreland, Pedro B. Carneiro, Jeremiah Johnson, and Christian Grov “Why Are Patients Switching from Tenofovir Disoproxil Fumarate/Emtricitabine (Truvada) to Tenofovir Alafenamide/Emtricitabine (Descovy) for Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis?” AIDS Patient Care STDS. August 2021; 35(8): 327–334. The study highlighted concerns around monies given to physician’s prescribing Descovy from Gilead Sciences. The authors state that “Data from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services reveal that in 2019, Gilead Sciences distributed $22,977,009 in the form of 97,709 payments to physicians across the United States. These payments include payments for speeches, consultation, travel, and lodging for physicians, as well as gifts of food and beverages. Pharmaceutical gifts and their influence over physician decision making are well documented in the literature.”

[13] Adam Fein “The 340B Program Climbed to $44 Billion in 2021—With Hospitals Grabbing Most of the Money” Drug Channels, 2022.