Insight

December 5, 2023

Employment-based Immigration Policy in the United States: Challenges and Reforms

Executive Summary

- The United States faces a shortage of workers in the near term and demographic trends indicate such pressures will continue to strain the labor pool over the longer term.

- The current U.S. employment-based immigration system has long-standing problems that make it unable to remediate these shortages: It caps the number of workers at unrealistically low levels, allocates them inflexibly and inefficiently, and processes cases too slowly.

- Congress should act to reform the system to admit more workers, process those workers more rapidly, and allow greater flexibility in visa status and mobility across the economy.

Overview and Introduction

The United States has both a near-term and long-term labor problem. With 1.6 job openings for every unemployed worker, employers are struggling to find needed talent. The problem is especially acute for skilled workers. As one source put it, “There is mounting concern among some US lawmakers about the nation’s ongoing shortage of health-care workers…[In May of this year], in areas where a health workforce shortage has been identified, the United States needs more than 17,000 additional primary care practitioners, 12,000 dental health practitioners and 8,200 mental health practitioners, according to data from the Health Resources & Services Administration.”

The story is the same elsewhere. In June, construction and manufacturing had nearly 1 million job openings out of the roughly 8.5 million open jobs across the economy. In addition, when looking across different industries, the transportation, health care and social assistance, and the accommodation and food sectors have had the highest numbers of job openings.

That shortage of labor is, of course, leading to slowdowns in the manufacturing of essentials goods, including semiconductors. For example, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company reported that its “production due to start next year at its first plant in Arizona would be delayed…until 2025 due to a shortage of specialist workers.” The excessively tight labor market feeds rising wages and inflation, and firms must pass on profitable opportunities due to the lack of manpower.

The shortfall exists across the economy and is likely to persist. “Deep-seated and long-term supply dynamics will continue to be a major force that creates a persistent gap between employer demand for new hires and the supply of candidates” said Svenja Gudell, chief economist at Indeed.

The key factor is demography, particularly low fertility and an aging population. As The Week’s Damon Linker put it:

Replacement-level fertility – the number of babies each woman, on average, needs to have in order for the country’s population to hold steady – is 2.1 births per woman. As recently as 15 years ago, the U.S. was bucking the trend of many peer nations in Europe and Asia in averaging about 2.1. But since 2007, the year before the start of the financial crisis and the extended recession that followed, we’ve fallen off a cliff. By 2019, the average number of births per woman had fallen to 1.71, and last week the [Centers for Disease Control and Prevention] announced that the number dropped to 1.64 in 2020. That most recent downtick may be partly driven by the COVID-19 pandemic, but it’s not divergent enough from recent trends to suggest there will be a reversal once the pandemic passes.

The retirement of the Baby Boom generation is swelling the ranks of retirees entering the large entitlement programs that rely on labor taxes for their funds, raising the specter of a future of smaller cohorts of workers paying higher taxes in a slower-growing economy. In 2023, there are 2.7 workers for each retiree in the Social Security program, a ratio that is expected to decline to 2.3 by 2035. This 15 percent decline implies that if nothing else changes, each worker’s taxes would need to be 15 percent higher. This corresponds to raising the payroll tax rate from 12.4 percent to 14.2 percent.

At the intersection of these challenges lies U.S. policy toward employment-based immigration. Historically, immigration built the U.S. economy, and the need to increase the U.S. labor supply makes reforming current immigration policies central to our economic future. Reforms should allow more permanent immigrants and temporary visa holders of all skills to meet the needs of today’s labor market. Permanently higher immigration would offset the demographic decline, raise innovation and productivity, create new firms, raise economic growth, and better support the lives of future seniors and workers alike.

This insight reviews the state of the labor force in the near term and into the foreseeable future, examines the problems with the current policy toward employer-based immigration, and offers potential reforms.

The Outlook for Labor in the United States

The United States has a tight labor market and scarcity of workers. At present, there are 1.6 job openings for each of the 5.8 million unemployed workers. This reflects the fact that the labor force participation rate, 62.6 percent, remains below the pre-pandemic 63.3 percent rate in February 2020. Total employment is only 60.4 percent of the population – again, below the 61.1 percent figure in February 2020. Employers are quite aware of the tight labor market situation as quit rates (the fraction of employed workers quitting their jobs) reached a record high of 3.0 percent in April 2022 before settling at 2.4 percent in the most recent survey.

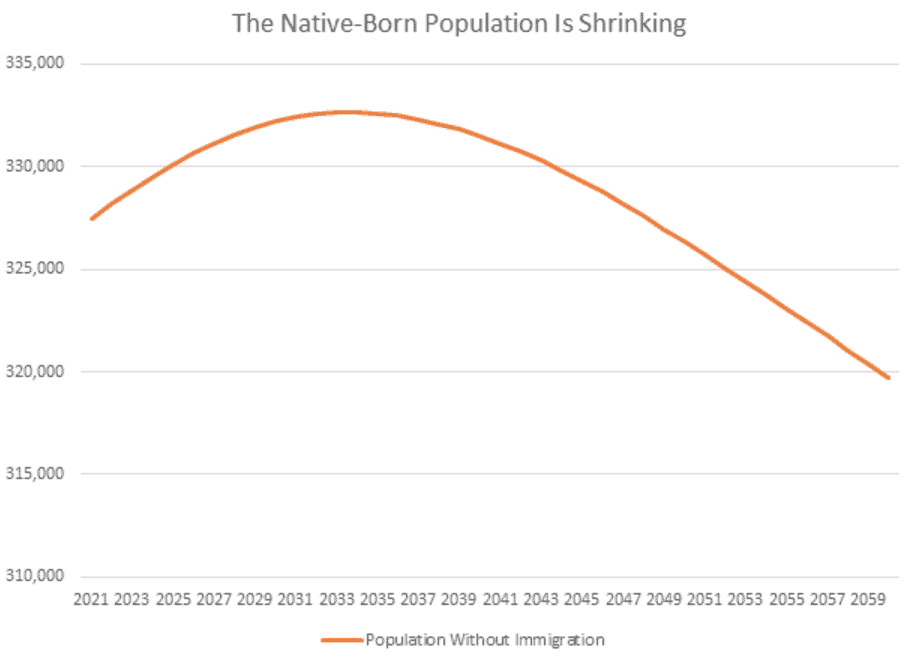

Over the longer term, low levels of fertility and increasing retirement rates will only further shrink the size of the labor force. The decline in fertility is a long-standing trend among native-born Americans. Fertility is below the replacement rate. Indeed, as displayed in the chart below, low fertility ultimately translates into a shrinking native-born population.

The reform of employment-based immigration can address the near-term scarcity of labor, as well as the looming demographic crisis created by low fertility and the retiring Baby Boom generation. The latter is an enormous demographic force, with the number of individuals aged 65 and older rising from 58 million in 2022 to 75 million in 2035.

Thus, the economic case for a better employment-based immigration system rests on meeting near-term needs and fostering more rapid long-term economic growth. More recently, a third element has arisen: international competition for skilled workers. It has long been true that if U.S. companies do not hire the best people, their competitors will. (See The Business Roundtable.) A Society for Human Resource Management survey found that “74 percent of employers reported that the ability to obtain work visas in a timely, predictable and flexible manner is critical to their organization’s business objectives. [Thirty-five] percent of respondents whose organizations are subject to the H-1B visa cap [for high-skilled workers] reported that they had lost key organizational talent due to H-1Bs being unavailable under the cap.”

More recently, the competition has risen to the outright raiding of skilled U.S. immigrants by global competitors. As a piece in The Washington Post noted:

To attract talented tech workers, Canada…[offered] 10,000 work permits to foreigners who are now in the United States on H-1B visas. This might be the first time any country has created an immigration program that hinges entirely on another country’s system.

This suggests that the Canadian government holds two opinions of U.S. H-1B visas: That they are good at attracting the world’s most talented immigrants. And that the ultimate value proposition to prospective immigrants is so weak long-term, that, given the option, many H-1B visa holders will head north to Canada.

Indeed, all the slots were filled within 24 hours of the launch of the new program.

In short, at present the near-term outlook for labor is scarcity, the long-term trend is slowing population growth, and the United States’ global competitors are more successful in attracting high-skill immigrants. Net immigration will account for all U.S. population growth starting in 2042, according to the Congressional Budget Office. Labor force growth roughly mirrors the pace of population growth, with the result that immigration will become the central element of U.S. economic growth.

The State of Employment-based Immigration

The employment-based immigration system is beset by numerous challenges: There are too few immigration opportunities, processing visas takes too long, the system is too inflexible, and there is too little focus on skills and entrepreneurship.

The primary temporary visa for high-skilled employment purposes is the H-1B visa. The total number available for U.S. businesses to hire skilled foreign nationals has been capped at 85,000 since 2004. This is well below the demand for workers, as 483,927 individuals registered for the H-1B visa in 2023. The fees to obtain an H-1B visa can total as much as $8,500 and the process can take seven months or longer. Given the substantial investment, employers focus H-1B hiring on high-skilled positions. In 2021, the median wage for H-1B workers was $108,000 and almost 70 percent had an advanced degree.

In addition to an inadequate overall limit, no country can exceed 7 percent of the visas, an unrealistic cap on populous countries such as India. The result is long wait times for skilled workers and an inflexible system for employers.

H-1B workers cannot change jobs and it can be difficult for employers to promote them. They cannot go unemployed for more than 60 days and cannot start businesses. Regardless of how long they have been in the United States, their children lose their dependent status when they turn 21.

These challenges are compounded by the caps and long backlogs for employment-based permanent residence (green cards). H-1Bs are the starting point for most employer‐sponsored permanent green cards. As noted above, this provides an opportunity for America’s competitors to poach talented workers; Canada explicitly targets U.S. holders of H-1B visas by offering a quicker route to permanent status. This is especially attractive to nationals from populous countries subject to the country-specific caps.

Since the H-1B category is dominated by the highly skilled and highly paid, the United States is lacking a robust source of legal visas for year-round, lower-skilled workers. This is an impediment for employers and likely contributes to illegal immigration. U.S. employers are unable to meet their demands for immigrant workers in the current system.

Options for Reform

To address the pressing needs of the U.S. economy, employment-based immigration reforms should admit more employment-based immigrants, expedite the admission of employment-based immigrants, and allow more flexibility in employment-based immigration.

Expand Employment-based Immigration

The most straightforward reform would be to raise or eliminate the cap on H-1B visas. These caps are largely arbitrary, and each year the business community’s demand for labor significantly exceeds the supply of visas available. This dynamic can easily be seen by examining demand for H-1B visas, which is widely utilized as a dual-intent visa by foreign students and other non-immigrants hoping to transition to employment-based green cards. Over the past five years, U.S. businesses have filed on average 212,000 H-1B petitions in just five days, far exceeding the cap of 85,000. Similarly, employer-filed petitions for green cards have more than doubled since 2013.

A more modest form of expansion would be to permit the spouses of H-1B visa holders to work. This would expand the total immigration and simultaneously enhance the flexibility of the system by providing a source of immigration less concentrated on skilled positions.

Expanding the H-2A and H-2B visa programs, which provide the United States with temporary workers in the agricultural and non-agricultural sectors, could also help to fill the gap between open positions and unemployed U.S. workers. The number of noncitizens that may receive an H-2B visas is currently capped at 66,000 per year. H-2A visas have no cap but are limited to temporary and seasonal work. Increasing the cap on H-2B and issuing more H-2A visas would benefit both employers and immigrants. These visas are temporary, however, so coupling this policy with legislation that would provide green cards to these workers after multiple years of productive service to one employer would establish an option for permanent economic migration, incentivizing the H-2A and H-2B system over the border for migrants seeking employment.

Another valuable reform would be to create new visa categories for year-round temporary workers at all skill levels and entrepreneurs interested in starting a business in the United States.

Address Backlogs and Reduce Processing Times

The U.S. immigration system is byzantine and slow-moving. Every effort should be made to make it simpler and faster. A starting point is addressing the backlog. There are about 8.6 million immigration benefit applications pending before United States Citizenship and Immigration Services, of which 5.2 million are considered part of the agency’s backlog. While the agency has faced backlogs before, disruptions posed by the COVID-19 pandemic substantially increased benefit application backlogs.

Eliminating the backlogs will require significant and sustained additional congressional funding; examining a number of different staffing scenarios, eliminating the backlog could take as little as two years or as long as eight years and could cost between $3.0–$3.9 billion. Yet eliminating the backlog could contribute as much as $110 billion per year in additional real gross domestic product and build a more sustainable U.S. workforce. This new national income would likely have a modest but positive budgetary effect over the next decade.

A second option to make the system quicker is Schedule A reform. To hire foreign workers, employers must first complete a permanent labor certification (PERM) which, due to its current one-year processing time, makes supplementing native-born labor with immigrants an unrealistic solution to the U.S. labor shortage. Reforming the PERM process would provide a longer-term solution to improve access to high-skilled immigrants but would likely be a lengthy endeavor. In the meantime, updating the Department of Labor’s Schedule A, a list of occupations facing native-born worker shortages, to reflect current labor needs would allow many employers to bypass the PERM process and expedite the hiring of foreign workers.

Allow More Flexibility in Employment-based Immigration

It would be desirable to introduce greater flexibility into the employment-based immigration system. As noted earlier, it makes sense to eliminate the country-based caps on H-1B visas. It would also be desirable to make it easier for H-1B visa holders to change employers and to easily transition from temporary to permanent status.

Finally, such a system should flexibly match skills to labor market needs. As an example, a colleague and I proposed a two-part reform to the U.S. system of granting permanent visas centered on credentials for education and skills and on proven work histories in the temporary visa program.

The reform proposes employing a point system to identify highly educated, highly skilled, and entrepreneurial workers. Those with sufficient points would be admitted, somewhat analogous to an employer reading resumes.

Workers who didn’t receive a formal education should also have reasonable immigration opportunities, provided they demonstrate value in the market. Specifically, they would be eligible for admission to a temporary worker program, and those who demonstrate sustained labor-market success may transfer to the permanent visa program. As with the current system, individuals granted permanent residency would be eligible to apply for citizenship after five years in the United States.

Conclusion

The U.S. employment-based immigration system has long-standing problems. It is time for Congress to reform employment-based immigration policies to admit more workers, do so more quickly, and allow greater flexibility in visa status and options for employment. Failure to act carries a cost: U.S. firms will continue to lose out to more nimble international competitors and U.S. supplies will continue to be restricted as businesses are unable to pursue profitable opportunities.