Insight

January 8, 2025

Evaluating the IRA’s Clean Energy Tax Provisions

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Congress is likely to revisit the Inflation Reduction Act’s 22 clean energy tax provisions – among them production and investment tax credits, transportation-related tax credits, and other tax incentives for carbon emissions mitigation and energy efficiency – as part of a broad tax reform debate in the new year.

- When debating whether to repeal, restructure, or otherwise reform these clean energy tax provisions – which are estimated to cost more than $870 billion between 2022–2031, more than double the initial cost estimate – lawmakers would benefit from using a framework of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability.

- Among other things, lawmakers could consider removing the complex eligibility and bonus credit requirements and modifying the industry-specific tax provisions to be technology-neutral, as well as repealing some or all the clean energy tax provisions, which would save as much as $852 billion from 2026–2035.

Introduction

As part of a broad tax reform debate in the new year, lawmakers may revisit the extensive clean energy tax provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 is, among other things, a major piece of federal climate legislation that includes 22 new or expanded tax provisions for clean energy investment, climate mitigation, and energy efficiency. The goal of these tax provisions is to reduce the U.S. reliance on fossil fuels, lower greenhouse gas emissions, and encourage employment in the clean energy sector. Additionally, the IRA includes a methane tax and direct spending programs on climate and energy policies such as grants and loans.

The IRA’s clean energy-related tax provisions fall into three broad categories: production and investment tax credits, transportation-related tax credits, and other tax incentives. Production and investment tax credits are aimed at encouraging clean energy producers to develop and invest in clean energy technologies. Transportation-related tax credits include those for clean vehicles and clean fuels. Other tax provisions are designed to encourage carbon management, commercial and residential energy efficiency, and clean energy research and development.

According to the Congressional Budget Office’s (CBO) latest estimate, the cost of all the IRA’s energy provisions (tax provisions and direct-spending programs) between 2022–2031 is $870 billion – more than double the initial estimate, and far more than the estimated revenue raised through the legislation’s revenue provisions.

Should Congress choose to repeal all the IRA’s clean energy tax provisions fully, it would raise revenues by more than $852 billion over 2026–2035. The largest credits are the production and investment tax credits, which if repealed would raise $437.7 billion from 2026–2035. The transportation-related tax credits would raise $104.7 billion over the same window. The remaining tax provisions, if repealed, would raise $89.7 billion.

Although income tax is not necessarily the best tool to address climate change, if lawmakers choose to continue all or some of the IRA’s clean energy tax provisions, they should design them to follow the principles of good tax policy: simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability. This insight provides an overview of the IRA’s major clean energy tax provisions, as well as a framework to evaluate its key provisions with these principles in mind.

The IRA’s Clean Energy Tax Provisions

The IRA included 22 new or expanded tax provisions for clean-energy development, carbon emissions mitigation, and energy efficiency. Generally, the IRA’s tax provisions are available to either producers or consumers. The producer-oriented tax provisions are meant to encourage investment in and production of green energy, carbon capture, and carbon sequestration. The consumer provisions include the clean vehicle tax credits and residential energy efficiency credits.

Clean energy tax credits

The IRA’s clean energy tax incentives fall into three categories: production and investment tax credits, transportation-related tax credits, and other tax incentives.

A summary of the targeted economic activity, rate, expiration date, and special features of all the clean energy tax provisions is included in the table in the appendix.

The IRA’s production and investment tax credits are designed to incentivize clean energy producers to develop and invest in clean energy technologies. Although each type of credit has a different structure, both production and investment credits work by reducing the after-tax cost of a new green energy project. The production credit reduces the after-tax cost by lowering the taxes on each unit of output for a new project, while an investment credit reduces the after-tax cost by subsidizing the purchase of the capital asset. Taxpayers can choose to use either the production or investment tax credits.

There are several tax credits related to the transportation sector for clean vehicles and fuels. The largest of these is the clean vehicle tax credit, a consumer-oriented tax credit that reduces the cost of certain qualified clean vehicles. Additionally, the IRA introduced new tax credits for clean fuel producers, including a new clean fuel production credit and sustainable aviation fuel credit. It extended two existing fuel-related credits, including the tax credit for biodiesel and renewable diesel and the second-generation biofuel incentives tax credit.

The IRA also introduced and extended a handful of tax incentives aimed at encouraging carbon management, commercial and residential energy efficiency, and clean energy research and development.

Domestic content, income thresholds, and bonus credit requirements

The IRA’s clean energy tax credit provisions include numerous requirements for taxpayers to be eligible to claim the full credit. For example, one prominent IRA requirement is the “Buy American” rule, which is applicable to incentives such as the clean vehicle credit, clean energy production and investment tax credits, and advanced manufacturing production credit. This rule requires certain input materials and product components to be either sourced from or assembled in the United States.

In addition to content limitations, producers can claim bonus incentive credits if they meet specific criteria. For example, producers can claim larger credits if they locate a project in certain communities (those in which fossil fuel production is located, low-income communities, or tribal land) or meet prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements (requiring them to pay workers no less than the prevailing wage rates and hire registered apprentices for a specified amount of time).

For consumer-based credits, such as the electric vehicle credit, there are also income threshold requirements. To qualify, a tax filer’s adjusted gross income must not exceed $75,000 ($150,000 married filing jointly or a surviving spouse, or $112,500 for heads of households).

Refundability and transferability

To expand the generosity and availability of the clean energy tax credits, the IRA added new features of transferability and refundability to the credits.

Under current law, clean energy credits such as investment and production credits are considered “general business credits.” The sum of all general business credits can offset up to 75 percent of a business’s tax liability in a year. Any excess credit needs to be carried forward into future years in which the business is not subject to this limitation. As a result, businesses with little or no tax liability are unable to fully utilize credits for the years in which they qualified.

Prior to the IRA, certain clean energy credits could circumvent this limitation through tax equity transactions. In the transaction, a clean energy developer partners with an outside investor on a clean energy project to utilize the tax credit. An investor is required to invest in the clean energy project directly to enter the transaction. With taxable income, the investor could use the credit instead of the energy developer. In exchange, the clean energy developer receives capital investment in its project.

The IRA made it much easier for clean energy developers to utilize the federal tax subsidies in two ways. First, some tax credits are now refundable or referred to as “elective pay” or “direct pay,” meaning that taxpayers with no tax liability can simply receive a payment from the federal government instead of having to carry forward excess credits. Second, taxpayers can sell their tax credits to a third-party investor for cash, but the investor is no longer required to invest in the clean energy project directly.

SIMPLICITY, EFFICIENCY, AND FISCAL SUSTAINABILITY

The IRA utilized the income tax in a number of ways to encourage the production of renewable energy. Although income tax is not necessarily the best tool to address climate change, these policies should strive to conform to principles of good tax policy. Ideally, tax policies should be simple, efficient, and fiscally sustainable. This allows the federal government to incentivize clean energy development without imposing unnecessary burdens on taxpayers and the economy.

A simple tax credit is one that makes it easy for the government to implement clean energy tax incentives and the taxpayers to utilize them, keeping both administrative and compliance costs low.

An efficient tax credit would ensure that eligible taxpayers can utilize clean energy tax credits as much as possible to help drive the economy’s transition to clean energy technologies. It should also limit the extent to which the tax incentives distort producers and consumers’ behaviors in ways that impose additional costs. It is worth noting that there is a tension between efficiency of clean energy tax credits and the conventional meaning of tax efficiency, as clean energy tax credits are designed to change taxpayers’ behaviors and encourage them to switch to consumption of clean energy technologies.

A fiscally sustainable tax credit is one that limits budgetary costs and can ultimately be financed through a low level of taxation.

Simplicity

The IRA’s tax credits are designed with more complexity than necessary. As discussed above, many of the IRA’s clean energy tax credits have several requirements that significantly narrow the eligible taxpayers to a targeted group of businesses or individuals, requiring regulators to dedicate more resources to screen and verify eligibility and taxpayers to incur a larger burden to comply with the requirements.

Tax credits can be simple to implement if they have universal provisions. If they are designed to benefit certain taxpayers or activities, however, the multiple layers of eligibility requirements could substantially increase the administrative and compliance costs. For example, the Internal Revenue Service has an extensive list of requirements for taxpayers to qualify for the new clean vehicle tax credit. The categories of requirements include use of the vehicle, adjusted gross income thresholds, battery capacity, “Buy American” requirements for critical minerals and battery components, location of vehicle final assembly, vehicle weight, manufacturer qualifications, and vehicle retail prices. These eligibility requirements make the clean vehicle tax credit complicated to administer and create barriers for taxpayers to claim the full credits. In fact, the clean vehicle tax credit performs poorly against all three principles as it is complicated, inefficient, and costly. (See more analysis in the sections below)

For many of the production and investment tax credits, the IRA’s bonus credit requirements (among them domestic manufacturing requirements and location of communities) also increase the complexity of the eligibility of the tax credits and makes it harder for taxpayers to fully benefit from the credits.

It is important to note that while simplifying the eligibility requirements would lower the administrative and compliance burden, it would also make the provisions more costly, as more taxpayers would be able to qualify for the subsidies. It is ultimately up to the political negotiation process to determine the design choices of the energy tax provisions and balance their trade-offs.

Efficiency

The IRA clean energy credits have a mix of features that make them inefficient in some ways and more efficient in others.

Features including the bonus credit requirements, industry-specific eligibility, and indirect pricing of carbon emissions are features that cause inefficiency in the IRA clean energy credits.

The “Buy American” and the prevailing wage and apprenticeship requirements make clean energy projects more costly and cause delays in clean energy development projects. In many cases, domestic products may be more expensive than imported goods, and in some cases the United States does not manufacture certain products. Furthermore, requiring project developers to hire registered apprentices and pay them artificially high wages may also cause project delays and raise project costs. Developers must then spend extra time looking for qualified registered apprentices and pay them the mandated wage instead of market-based wage.

Industry-specific clean energy tax credits also cause inefficiency. For example, the advanced manufacturing production tax credit is designed for producers that manufacture clean energy products (e.g., solar and wind products, battery components, and critical minerals) in the United States. This credit distorts the market incentives by subsidizing certain manufacturing industries when the resources could have been more efficiently dedicated to other economic activities that yield higher productivity. There is also inefficiency in other credits. A Stanford University study found that about 75 percent of the clean vehicle subsidies in the IRA were given to consumers who would have bought an electric vehicle anyway. Efficient clean energy tax credits should be applicable to a broad base of taxpayers. The more targeted a tax credit is, the more likely it is to produce inefficiency.

Tax credits, in general, are less effective in reducing greenhouse gas emissions than a direct pricing mechanism such as a carbon tax. This is especially true for the IRA’s consumer-based credits. For example, the new clean vehicle tax credit incentivizes consumers to switch from combustion-engine vehicles to electric vehicles, reducing gasoline consumption, although electric vehicles may still be indirectly charged with electricity produced by fossil fuels, such as coal, rather than renewable energy. A direct carbon price, on the other hand, would encourage the use of clean vehicles and consumption of clean energy.

Moreover, subsidy-based green policies, such as tax credits, do not require households to economize. As a result, some tax dollars are wasted in an increase in overall energy consumption. This is because the IRA’s tax subsidies make clean energy cheaper and therefore reduce overall energy prices. While some consumers may switch to clean energy instead of carbon-intensive energy, others may increase their total energy consumption due to the subsidies.

In contrast, refundability and transferability are efficiency-enhancing features of the IRA credits. These provisions allow businesses to receive the full value of the subsidies for which they qualify. For example, a startup energy storage technology company is not typically profitable in its first few years of business, which means that it does not have any taxable income or tax liability. As a result, it cannot use any standard tax credits to reduce its tax liability. With the refundability and transferability features of the IRA’s tax credits, the startup company can either get a refund (a direct payment) from the government as if it had a tax liability or sell the tax credit to another business for cash.

The market for these credits has generally priced these credits close to their face value. Recent research estimated that buyers have been willing to pay between 85–95 cents per dollar of energy tax credit.

Fiscal sustainability

The United States has a bleak long-term fiscal outlook, with the national debt projected to reach 166 percent of gross domestic product by the end of 2054 under current law.

Initially, the IRA’s clean energy provisions were projected to cost the federal government roughly $400 billion over 10 years. These costs were offset by two new taxes. The first tax was the corporate alternative minimum tax, which was projected to raise $222.2 billion from 2022–2031. The second tax was a 1-percent excise tax on stock buybacks, projected to raise $73.6 billion over the same period.

Earlier this year, CBO estimated that the cost of all the IRA’s energy provisions (tax provisions and direct spending programs) between 2022–2031 has more than doubled to $870 billion. This cost far exceeds the estimated revenue raised through the corporate alternative minimum tax and the 1-percent stock buyback excise tax.

One of the main drivers of the higher cost estimates is the Environmental Protection Agency’s proposed rule to significantly raise the emissions standards for light and medium-duty vehicles to encourage a swifter shift toward clean vehicles. Another important factor is that the actual demand for clean energy technologies has exceeded expectations. As a result, the IRA’s revenue provisions raise far too little to cover the costs of these credits.

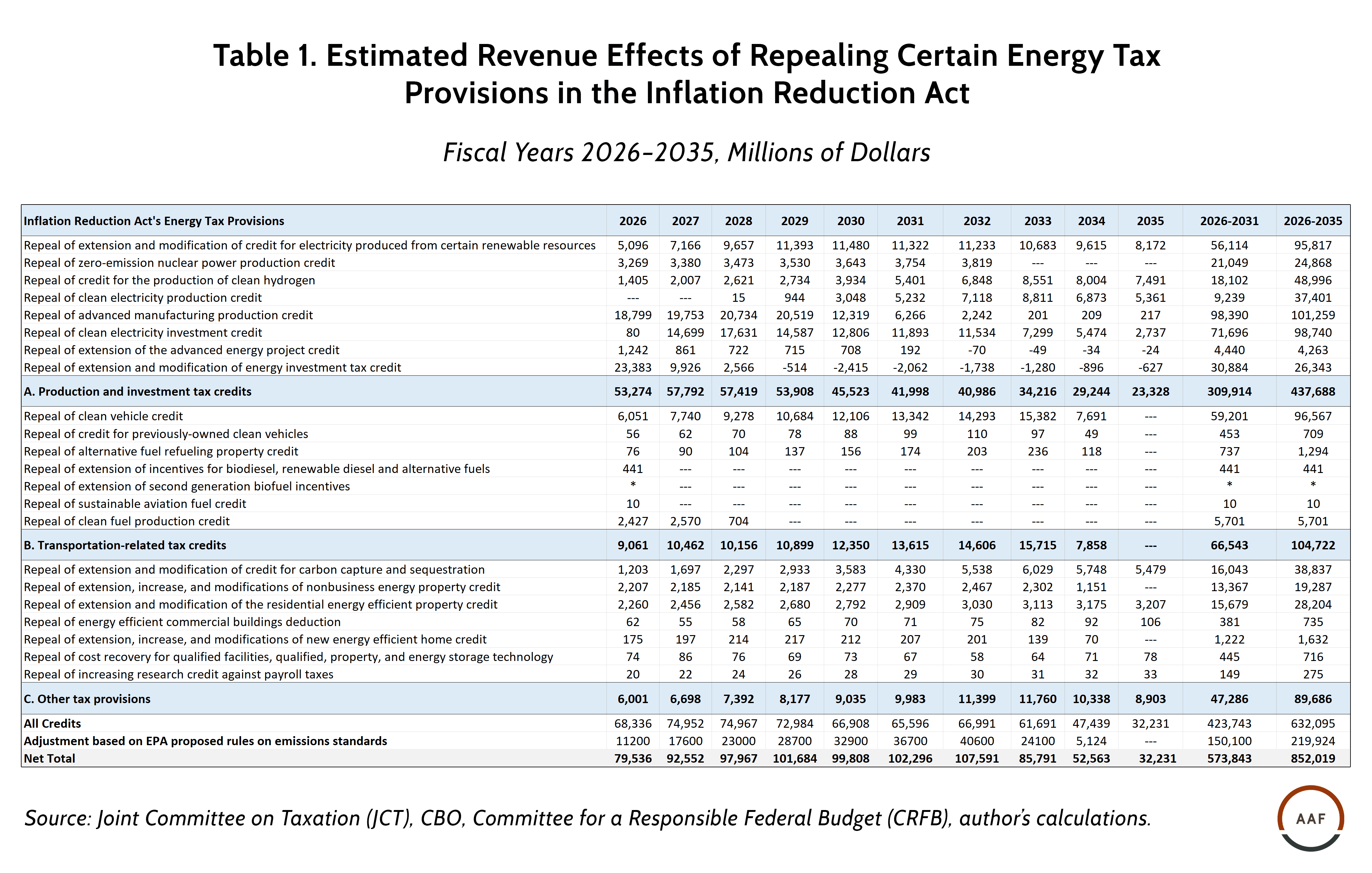

The table below shows how much revenue would be raised between 2026–2035 if Congress were to repeal the IRA’s clean energy tax incentives. The tax incentives are listed across three buckets: production and investment tax credits, transportation-related tax credits, and other credits. (See the summary in the overview section above).

The largest credits are the production and investment tax credits, which if repealed, would raise $437.7 billion from 2026–2035. The transportation-related tax credits would raise $104.7 billion over the same window. The remaining tax provisions have the smallest budgetary impact, raising $89.7 billion if repealed. In sum, fully repealing all the IRA’s energy-related tax provisions would raise $852 billion.

- As of December 2024, JCT provided revenue estimates of a full repeal of the energy tax provisions for 2023–2033. The author provided estimates for a new window of 2026–2035 and calculated the revenue estimates for 2034 and 2035 based on author’s interpretation of the legislative text and U.S. Treasury’s policy guidance.

- The author incorporated the CBO’s latest higher cost estimates of some energy provisions in the revenue estimates based on EPA’s proposed rules on emissions standards.

- * Denotes revenue of less than $500,000.

CONCLUSION

In evaluating the IRA’s energy tax provisions during the coming tax reform discussions, Congress should use the framework of simplicity, efficiency, and fiscal sustainability. There are ample opportunities to improve the IRA’s energy tax provisions following those three principles.

Removing the domestic content, income thresholds, and bonus credit requirements would make the energy tax provisions significantly simpler, allowing a broader group of taxpayers eligible to utilize them. Simplifying the tax provisions would also lower the administrative burden to implement them and reduce the compliance burden to claim them.

Removing the domestic content and bonus credit requirements and modifying the industry-specific provisions to be technology-neutral would also enhance the efficiency of the energy tax provisions. Additionally, lawmakers should maintain the transferability and refundability of the tax provisions as efficiency-improving features.

Finally, however lawmakers choose to modify the IRA’s energy-related tax provisions, it should keep fiscal sustainability – and the law’s updated price tag – in mind.

APPENDIX

Table 2. Summary Of the Clean Energy Tax Provisions in the 2022 Inflation Reduction Act

| Tax Provision | Targeted Economic Activity | Rate | Expiration Date | Special Features |

| A. Production and investment tax credits | ||||

| Extension and modification of credit for electricity produced from certain renewable resources | Electricity production via specific renewable energy resources, e.g. solar, wind, hydropower | 0.3 cents per kilowatt hour of clean electricity, inflation adjusted | Ends in 2024 and will be replaced by the clean electricity production credit starting January 1, 2025. Available for a 10-year period starting the date the facility is placed in service. |

|

| Zero-emission nuclear power production credit | Electricity production via nuclear energy | 0.3 cents per kilowatt hour of clean electricity, inflation adjusted | December 31, 2032 |

|

| Credit for the production of clean hydrogen | Production of qualified clean hydrogen (QCH) | Base credit: $0.6 per kg of QCH, inflation adjusted; multiplied by an applicable percentage (20100%) based on the level of lifecycle greenhouse gas emissions | QCH facilities must be constructed before January 1, 2033 (credits available for the first 10 years of service) |

|

| Clean electricity production credit | Production of clean electricity with unspecified technology | 0.3 cents per kilowatt hour of clean electricity, inflation adjusted | Will start to phase out after the later of 2032, or when the United States meets the electricity sector’s emissions reduction goal. |

|

| Advanced manufacturing production credit | U.S. production of eligible clean energy technology components, e.g., wind turbines, battery components, critical minerals | The rate varies depending on the eligible component; more details here | The credit for critical minerals is permanent; starts to phase out in 2030 with a reduction of 25% annually over four years. |

|

| Clean electricity investment credit | Qualified investment in clean electricity production from unspecified technology | At least 6% of the qualified investment costs to producers of qualified clean electricity

|

Will start to phase out after the later of 2032, or when the United States meets the electricity sector’s emissions reduction goal. |

|

| Extension of the advanced energy project credit | Qualified investment in eligible low-carbon energy projects, e.g., building facilities for the production of carbon removing and capturing equipment, or a project that would reduce the greenhouse gas emissions of a facility by 20% | Up to 30% of the qualified investment cost

|

Increased the funding for the credit from the original one-time allocation of $2.3 billion in 2009 to $12.3 billion. |

|

| Extension and modification of energy investment tax credit | Qualified investment in specific energy property development projects, e.g., solar, geothermal, wind, or energy storage properties. | 30% (10% for microturbine property) | Ends in 2024 and will be replaced by the clean electricity investment credit starting in 2025. |

|

| B. Transportation-related tax credits | ||||

| Clean vehicle credit | Purchases of qualified commercial clean vehicles | The credit is the lesser of 1) the costs of the clean vehicle that exceeds the price of a comparable combustion-engine vehicle; or 2) 15% of the vehicle price for hybrid vehicles, 30% for electric or fuel cell vehicles. | Not applicable to vehicles purchased after 2032. |

|

| Credit for previously owned clean vehicles | Purchases of qualified used clean vehicles | 30% of the used vehicle’s sales price up to $4,000 | Not applicable to vehicles purchased after 2032. |

|

| Alternative fuel refueling property credit | § The cost of qualified alternative fuel vehicle refueling property and vehicle charging equipment at a residential home or a business | § 30% of qualifying costs, up to $1,000 for personal property

§ 6% of the qualifying costs, up to $100,000 for business property. |

Property in service by the end of 2032 |

|

| Extension of incentives for biodiesel, renewable diesel and alternative fuels | Production of biodiesel, renewable diesel and alternative fuels | § $1 per gallon for biodiesel, biodiesel mixtures, and renewable diesel | Fuel used or sold by the end of 2024 |

|

| Extension of second-generation biofuel incentives | Production of qualified second-generation biofuel | $1.01 per gallon | Fuel produced before January 1, 2025

|

|

| Sustainable aviation fuel credit | Sale or use of qualified aviation fuel that reduces lifecycle greenhouse gas emission by at least 50% compared to conventional jet fuel | Base credit is $1.25 per gallon. | By the end of 2024 |

|

| Clean fuel production credit | Production of clean transportation fuel | Base credit is 20 cents per gallon of nonaviation fuel, 35 cents per gallon for aviation fuel. | Fuel produced starting from 2025 and sold by the end of 2027 (a two-year credit) |

|

| C. Other tax provisions | ||||

| Extension and modification of credit for carbon capture and sequestration | Capture and sequestration of carbon emissions at facilities (carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide) | § For carbon oxide not used as a tertiary injectant: $17 per metric and $36 for direct air capture.

§ For carbon oxide used as a tertiary injectant: $12 per metric and $26 for direct air capture. |

Construction of the equipment must start by the end of 2032 (a 12-year credit available after a facility is in service). |

|

| Extension, increase, and modifications of nonbusiness energy property credit | Qualified energy efficiency improvements to for residential property | A 30% tax credit for qualified energy-efficiency improvements, capped at $1,200 per taxpayer and $600 per item. | Efficiency improvements in place by the end of 2032 | Some equipment is eligible for a larger tax credit at $2,000, such as water heaters, heat pumps, air conditioners, boilers, etc. |

| Extension and modification of the residential energy efficient property credit

(renamed to be the “residential clean energy credit” in 2024) |

Qualified purchases of clean energy equipment, such as solar electric property, solar water heating property, geothermal heat pump property, etc. | Up to 30% of the cost of qualifying property depending on when the property is placed in service. | Property placed in service by the end of 2034 | The tax credit for fuel cells is capped at $500 per 0.5 kilowatt of capacity |

| Energy efficient commercial buildings deduction | Qualified energy efficiency improvements to commercial buildings | 50 cents to $1 per square foot, depending on efficiency improvement, with deduction over a four-year period, capped at $1 per square foot. | Permanent | Additional deduction amount from $2.5 to $5 per square foot for taxpayers that meet the prevailing wage and registered apprenticeship standards |

| Extension, increase, and modifications of new energy efficient home credit | Construction of a qualified new energy efficient home (single-family or multi-family homes) by an eligible contractor | Up to $5,000 per new efficient home built or reconstructed | Acquired before the end of 2032 | Eligibility for the maximum level of credit is conditioned on the prevailing wage requirements |

| Cost recovery for qualified facilities, qualified, property, and energy storage technology | Additional tax deduction for the same taxpayers that are qualified for the clean electricity production tax credit | Accelerated depreciation allowances as specified in the

modified accelerated cost recovery system (MACRS).

|

Available for five years starting from 2025 | N/A |

| Increasing Research Credit Against Payroll Taxes | Research and development activities of qualified small businesses | An annual tax credit of $500,000 against payroll taxes for qualified small businesses. | Permanent | Allows eligible businesses to use the credits against the employer portion of the Social Security and Medicare payroll tax liability |

Source: U.S. Treasury, U.S. Internal Revenue Service, Joint Committee on Taxation, Congressional Research Service, BLS & Co., Bipartisan Policy Center.