Insight

February 7, 2025

Evaluating Trump’s Newest Hiring Freeze

Executive Summary

- Among President Trump’s flurry of day-one executive orders was a 90-day hiring freeze on the federal civilian workforce, which in part orders the directors of the Office of Management and Budget, the Office of Personnel Management, and the United States DOGE Service (USDS) to submit a plan “to reduce the size of the Federal Government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition.”

- Although the stated goal of the president’s hiring freeze is to streamline the government workforce to reduce waste and inefficiency, the historical evidence indicates that blanket hiring freezes have not been an effective tool to that end: Past hiring freezes have not significantly reduced federal employment levels, and there is no clear evidence as to whether freezes reduce operating costs.

- This hiring freeze, however, differentiates itself from its predecessors in one significant way: It precedes a plan of action drafted by USDS, signaling perhaps some greater level of commitment from this administration to shrinking the size of the federal government.

Introduction

Among President Trump’s flurry of executive orders (EO) issued on the first day of his second term is a 90-day hiring freeze on the federal civilian workforce. The freeze does not apply to military personnel or to “positions related to immigration enforcement, national security, or public safety.” The EO also orders the directors of the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Office of Personnel Management (OPM), as well as the administrator of the United States DOGE Service (USDS), to submit a plan “to reduce the size of the Federal Government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition.”

Although the stated goal of the hiring freeze is to streamline the government workforce to reduce waste and inefficiency, the historical evidence indicates that blanket hiring freezes have not been an effective tool to that end. Past hiring freezes have not significantly reduced federal employment levels, and there is no clear evidence as to whether freezes reduce operating costs.

A 1982 Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, which summarizes the results of four freezes from 1977 to 1981, found that these freezes resulted in only small employment reductions. Furthermore, it was undetermined as to whether they resulted in net savings. Data from the more recent 2017 federal hiring freeze implemented by President Trump during his first term paint a similar picture, as one summary of the freeze found a modest reduction of 0.81 percent in permanent employment.

If past is prologue, Trump’s recent freeze is not likely to inflict more than a dent in the federal workforce and may not increase overall efficiency. The president’s latest freeze, however, differentiates itself from past freezes in at least one notable way: It incorporates USDS into the creation of a long-term plan to reduce the size of the federal workforce. Elon Musk, the billionaire entrepreneur and administrator of USDS, has stated ambitious goals to reduce the size of the federal workforce. While the president appears to actively seek Musk’s advice, most long-term, permanent reductions to the federal workforce will need to be enshrined by Congress into law.

Whether USDS’ recommendations will be accepted by Congress is another question entirely, and it is on this prospect that USDS’ success will hinge. The historical record of such commissions is not exactly favorable.

This insight walks through the historical record of federal hiring freezes from Presidents Carter and Reagan, as well as Trump’s previous freeze enacted in 2017, to shed light on what the president’s current freeze is likely to accomplish.

Examining the (Partial) Historical Record of Freezes

To forecast the results of President Trump’s recent hiring freeze, one can review the consequences of similar hiring freezes of recent historical memory. While there appears to be little available research on this topic, two reports provide some insight into the results of such freezes: a 1982 GAO report that studied four freezes from 1977 to 1981 and an independent brief on Trump’s 2017 freeze.

1982 GAO Report

A 1982 GAO report studied four hiring freezes from 1977 to 1981, spanning across both the Carter and Reagan Administrations. Three of these freezes were imposed by the Carter Administration and one by the Reagan Administration. These freezes, similar to the recent Trump freeze, applied to most agencies (with some exceptions for national security and other purposes), regardless of their workload or their workforce requirements, with the stated intent to reduce the size of the federal workforce. The report, however, found that these across-the-board hiring freezes did not produce the desired outcome of trimming employment levels.

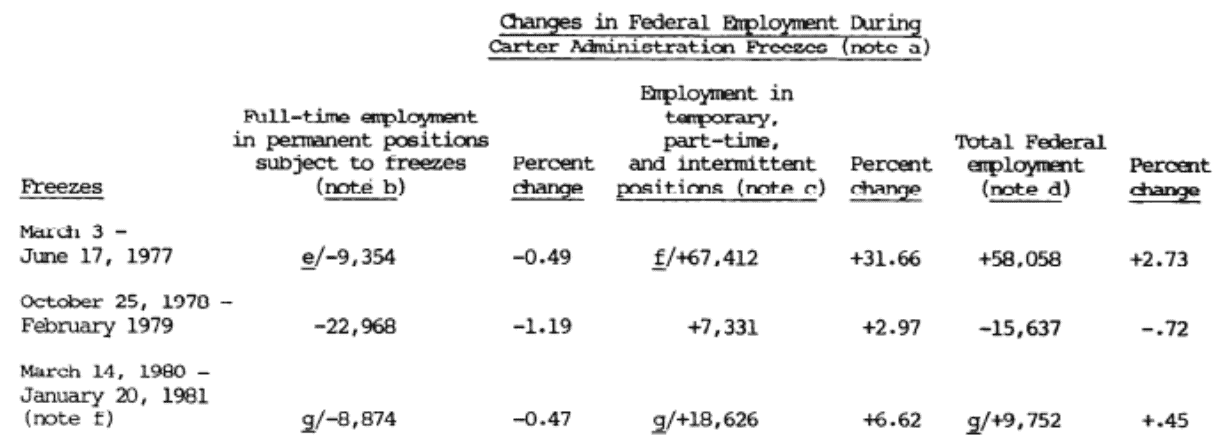

According to the OPM data below, there were only marginal reductions to full-time permanent employment levels during the freezes, as seen in the third column of the table. The report also explains that employment reductions during Carter’s first freeze were temporary: “After the freeze was lifted in June 1977, hiring increased so that by November, full-time employment in permanent positions was only 2,965 less than when the freeze began.”

Source: Government Accountability Office

Although this small decrease in full-time permanent employees may seem like some evidence for the efficacy of freezes, the data also suggest that exempted part-time and temporary employment rose, increasing total federal employment. While some of these increases can be explained by seasonal hiring patterns and higher personnel ceilings, GAO found instances in which agencies hired other types of employees, relied on contractors and overtime, and violated limitation guidelines by simply hiring more employees than allowed to compensate for the freezes.

Reagan’s 1981 hiring freeze produced similar results to those of Carter’s, with federal employment decreasing by only 0.1 percent. The report, however, found that employment levels during that time would have decreased even if the freeze had not been imposed.

At first glance, one might be led to believe that this reduction in the federal workforce, albeit small, would result in at least some cost savings for taxpayers. Yet according to the report, OMB did not determine any net savings from the employment reductions, as it did not “attempt to identify either gross savings in salaries and benefits or offsetting costs, such as hiring other than full-time permanent employees or using contractors or overtime.”

Trump’s 2017 Hiring Freeze

Perhaps the closest analogue to President Trump’s most recent hiring freeze was his 2017 freeze issued at the beginning of his first term in office.

Its results largely mirror those of the Carter and Reagan freezes covered in the GAO study. One brief covering the freeze found that the permanent workforce – so considered because omitting data on the temporary workforce reduces distortion from seasonal hiring – dropped from 1,962,965 workers at the beginning of the freeze to 1,947,048 by the end, a decrease of 0.81 percent.

Further disaggregating these numbers reveals that attrition at some agencies was particularly acute, while other agencies experienced net gains in employment. For example, OPM and the Department of Veterans Affairs saw increases of almost 2 percent. On the other hand, the Internal Revenue Service (IRS) during this period lost more than 6,800 permanent workers, or about 8.6 percent of its workforce.

Yet this culling of IRS employees was to be relatively short-lived. As shown in the graph below, full-time positions at the agency nosedived beginning in 2014, reached their nadir during the first Trump Administration, and rebounded almost entirely during the Biden Administration, owing in part to an Inflation Reduction Act provision to hire 87,000 workers.

Source: Internal Revenue Service

In other words, it is not as though Trump’s federal hiring freeze had no effect; rather, it had little staying power and was quickly and effectively reversed by the succeeding administration. Of particular note are the IRS’ operating costs from 2014–2023, which demonstrate that – even at an agency especially targeted by Trump’s 2027 hiring freeze – costs did not drop appreciably and later went on to rise substantially during the Biden Administration.

The Potential of Trump’s Recent Freeze

The data behind past blanket hiring freezes illustrate the limited effect they have on achieving their goal of streamlining the federal government through attrition and reduced operating costs. Past freezes have not been effective in reducing federal employment levels and saving taxpayer dollars. Furthermore, as seen in Carter’s first freeze in 1977 and Trump’s 2017 freeze, employment levels can rebound once a freeze is lifted, blunting the effects of executive branch hiring freezes.

Whether President Trump’s newest freeze will prove effective and durable in the long run depends in particular on future events and less so on the current structure of the president’s efforts. In large part this is a consequence of the agencies’ structure: Much of their duties are decided by the content of federal law, meaning that their workload is often outside the purview of executive control. In other words, while President Trump has some power to determine the number of workers employed by the federal government, he has less power to dictate what they do. Efforts to shrink the federal workforce without complementary efforts to shrink its duties are not likely to produce greater efficiencies.

Contingencies that will determine the efficacy of President Trump’s efforts include: the extent to which Congress pairs workforce attrition with legislative reform of the agencies; whether President Trump’s successor is aligned with his goals; whether the next Congress is similarly aligned; whether Trump’s efforts will be stalled or halted by the courts; and whether Trump’s other administrative priorities require a more robust executive branch, among other things.

Nevertheless, the new Trump Administration has clearly signaled a serious effort to trim the federal bureaucracy. First, the administration’s attempt to accelerate the process of attrition through a buyout of federal employees – offering eight months’ salary during which federal workers who accept the deal will stay remote without any of their assignments, and after which are terminated – is likely to entice at least some workers, though it is unclear exactly how many will accept.

Second, as with President Trump’s 2017 freeze, the latest one includes a provision mandating that the directors of OMB and OPM craft a plan to “reduce the size of the Federal Government’s workforce through efficiency improvements and attrition” – but in a modern twist, the plan will also require the input of the USDS administrator, Elon Musk.

Similar commissions, whose results skewed toward negligible, were so tasked in the past, including that of Trump’s OPM-OMB, whose report was – one assumes – not received warmly by the Biden Administration. More important, however, USDS’ recommendations must ultimately be accepted by Congress, which must then respond accordingly with legislation, a prospect that is not exactly a fait accompli.

If history is any guide, such reports do not usually result in pronounced congressional action. As the Ronald Reagan Presidential Library and Museum recounts of the 40th president’s Grace Commission – which produced 2,478 cost-cutting and revenue-enhancing recommendations that would have resulted in $424 billion in savings over three years – “most of the recommendations, especially those requiring legislation from Congress, were never implemented. However, the Commission’s work provided a starting point for many conservative critiques of the federal government.”

If such a fate awaits USDS’ forthcoming report, it would represent the rule and not the exception.