Insight

May 17, 2021

Foreign-Derived Intangible Income Taxation – A Primer

Executive Summary

- The foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) provides a new tax preference for locating mobile intellectual property income in the United States.

- FDII relies on similar concepts and definitions as other policies established under the TCJA and is designed to act in concert with those policies to preserve the U.S. tax base while improving the investment climate in the United States.

- The FDII provision – a 37.5 percent deduction against income earned abroad that exceeds a deemed return on tangible assets – provides a reduced effective tax rate on high-return income, consistent with intellectual property income, and is similar in inspiration to “patent boxes” in other nations.

Introduction

In December 2017, Congress passed the most sweeping set of changes to the federal tax code since 1986. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) broadly reformed three major elements of the federal tax code: the individual income tax, the corporation income tax, and the tax treatment of international income. The third set of reforms moved the U.S. international tax regime to a nominally territorial system, but this change required a new set of rules to at once improve the tax climate for U.S. firms operating domestically and internationally while preventing the erosion of the U.S. tax base.

One such new policy relates to “foreign-derived intangible income,” or FDII. While the acronym refers to the type of income – income earned overseas from intangible assets – it has also become the shorthand for how that income is taxed. Specifically, the TCJA provides a tax preference for income that is earned abroad from intangible assets such as patents or trademarks located in the United States. Essentially, this policy was designed to make the location of such intellectual property (IP) in the United States more attractive for tax purposes, in a way similar to other nations’ “patent boxes.” Congress and the Biden Administration have proposed variously eliminating or scaling back this policy, but in so doing may, contrary to assertion, disadvantage U.S. firms and incentivize the location of U.S. IP overseas.

What Is FDII?[1]

A key element of the TCJA, and of many previous tax-reform plans, was to modernize the way the federal government taxes income that U.S. firms earn overseas. Prior to the TCJA, the United States imposed a worldwide tax, which subjected U.S. firms operating abroad to U.S. taxes on their overseas profits, although foreign subsidiaries of U.S. firms could defer those taxes by keeping their related earnings overseas, via a tax status known as deferral. The old system, particularly when paired with one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world, had a number of drawbacks, not least of which was the incentive for U.S. firms to “invert” and move their headquarters overseas.[2]

The TCJA contained a number of provisions that upended the old system, including replacing the worldwide tax system with a territorial system whereby the foreign-sourced income of U.S. firms would be exempt from taxation. In so doing, the United States joined 29 of the 34 economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that had adopted some form of a territorial system at the time.[3]

Notwithstanding the deficiencies of the prior U.S. international tax regime and the global trend toward territorial tax systems, territorial systems are not without their own complications. Territorial systems require complex rules to establish guardrails around a nation’s tax base, as in a territorial system, tax planners have every incentive to shift profits into low-tax foreign jurisdictions. [4] These types of rules, known as “base erosion” provisions, are designed to mitigate the incentives for taxpayers (think large multinational firms) to shift income abroad to avoid U.S. taxes. Accordingly, the international provisions of the TCJA introduced a series of new rules (and acronyms) to tax policy, including the “base erosion and anti-abuse tax” (BEAT), the Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income (GILTI), and the Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII). Each provision was designed to operate in coordination with other international elements and the TCJA more broadly.

The TCJA defines FDII as the income related to the sale or provision of intangible U.S. goods and services to foreign entities or for a foreign use. Essentially, the provision is designed to capture income that U.S. companies earn abroad from their intellectual property. The provision provides a 37.5 percent deduction against qualifying income earned by the U.S. firm. The deduction reduces the effective tax rate on this income to 13.125 percent, rather than the headline corporate tax rate of 21 percent. Beginning in 2026, the deduction for FDII is reduced to 21.875 percent, which in turn raises the effective U.S. tax rate on FDII to 16.406 percent. This shift is an artifact of the budget reconciliation process that was used to enact the TCJA, which necessitated curtailing certain tax preferences to avoid running afoul of Senate rules.

The FDII provision was designed to incentivize U.S. multinationals to bring and keep intellectual property and the associated profits in the United States. Rather than discourage specific activities or structures harming the U.S. fiscal interests, FDII aims to promote U.S. export activity. To put it simply, whereas GILTI and BEAT are designed to disincentivize base erosion, FDII is designed to incentivize the location of applicable income in the U.S. tax base. If the international tax provisions in the TCJA can be understood as sticks and carrots, GILTI and BEAT serve as the sticks while FDII is designed to be a carrot.

Calculating the FDII Liability

FDII income is defined as the excess income above a certain threshold multiplied by the share of the firms’ income attributable to exports. The following equation sets forth the key inputs and interactions for calculating liability:[5]

FDII = [Net Income – (10 percent X QBAI)] X [Foreign Derived Net Income/Net Income]

The threshold amount is 10 percent of the firm’s qualified business asset investment (QBAI). That the FDII provision is designed to operate in concert with the other aspects of the TCJA’s international reforms is plain from the inclusion of the concept of QBAI, which similarly underpins the TCJA’s GILTI policy. QBAI is essentially the tangible assets – such as machines and other equipment – that the firm uses to generate income. The rationale for this standard is that 10 percent represents a reasonable rate of return on a firm’s tangible assets. The deemed return on QBAI concept nominally targets income on intangible assets, but it really targets any income that can be defined as “excessive” measured relative to an assumed return on the firm’s tangible assets. Thus, both FDII and GILTI identify intangible income as essentially high-return income. The excess income is then multiplied by the percentage of a firm’s export-related income. The 37.5 percent deduction is applied to that export-related percentage of income that is in excess of the 10 percent deemed return on QBAI.

FDII by Example

To illustrate how FDII works, consider a hypothetical U.S. technology company. For the purposes of this example, assume the company earns total profits of $100 and that $50 of that profit is earned from selling goods or services overseas.[6] Further assume that the company has invested $500 in QBAI.

Figure 1: Hypothetical Firm

It is important to first note that the identification of these tax inputs for a given firm is in itself a complicated undertaking. Having done so, a firm must first determine its deemed intangible income, which is the firm’s income in excess of the 10 percent deemed return on QBAI.

Recall that the formula for determining FDII is as follows:

FDII = [Net Income – (10 percent X QBAI)] X [Foreign Derived Net Income/Net Income]

Thus, for this firm, this calculation would reflect the following inputs:

FDII = [$100 – $50] X [$50/$100]

FDII = $25

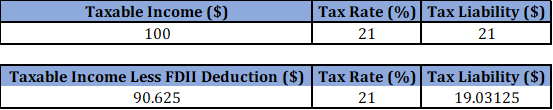

In this example, the hypothetical firm would have foreign-derived intangible income (FDII) of $25. The last step in determining a firm’s tax liability under the FDII provision is to apply the 37.5 percent deduction to a firm’s FDII income, which in this example would allow the firm to deduct $9.375 from its tax liability. Assuming a 21 percent tax rate, this reduces the effective tax rate on FDII income to 13.125, as opposed to 21 percent. For the firm overall, the deductibility of a portion of the foreign derived income reduces the firm’s effective tax rate. Assuming a 21 percent tax rate, in the absence of the FDII provision, the example firm’s tax liability would be $21. With the FDII deduction however, the firm’s effective tax rate drops to just over 19 percent.

Figure 2. Hypothetical Tax Liabilities With and Without a FDII Deduction

Essentially, the FDII policy provides an incremental tax benefit to locating IP in the United States for exporting, rather than locating that same IP abroad. It somewhat mimics other nations’ patent boxes, which provide reduced rates on IP-derived income, though the design of these policies varies across jurisdictions.

Conclusion

The TCJA was an assemblage of individual, business, and international tax reforms. The international tax reforms are likely the most significant departures from past policy in the law but are somewhat complex and have been subject to prolonged regulatory refinement. The alphabet soup of international tax regimes established under the TCJA are designed to act in concert to balance a number of priorities including preserving the U.S. tax base while improving the climate for investment in the United States. Achieving these goals has required a carrot-and-stick approach – and the FDII policy is the most conspicuous carrot among the major international policies. The FDII provision provides a clear, though relatively modest, tax incentive to locate highly mobile income in the United States, a policy embraced by a substantial share of major U.S. trading partners.

[1] Policy observers familiar with this topic divide on the pronunciation of this acronym. A primer on this subject would be horribly remiss to elide this debate: in this house, we call it “fiddy.”

[2] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/cost-inaction-tax-reform/

[3] https://taxfoundation.org/territorial-tax-system-oecd-review/

[4] See https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/The%20International%20Tax%20Bipartisan%20Tax%20Working%20Group%20Report.pdf and https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4656

[5] This uses somewhat simplified definitions of income for the purposes of explanation, for the technical definitions and statutory references see: https://www.jct.gov/publications/2021/jcx-16r-21/

[6] The term profits here is a simplification of the definition of “deduction eligible income,” DEI, while foreign-derived profits is a simplified term for the definition of “foreign-derived deduction eligible income,” both of which are defined in 26 U.S. Code § 250