Research

September 13, 2018

Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income Taxation – A Primer

Executive Summary

- The GILTI – Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income – provision of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act establishes a minimum tax on income that has similar characteristics to highly mobile intangible income.

- GILTI is defined as income in excess of what policymakers determined to be a normal rate of return (10 percent) on tangible assets.

- Taxpayers reporting GILTI face effective tax rates of at least 10.5 percent through 2025 and 13.125 percent thereafter on GILTI income.

- While the definition of GILTI may capture high-return intangible income, it really captures any income irrespective of source in excess of the deemed rate of return.

- Regulatory refinement will be essential to ensuring that the GILTI provision does not have the unintended effect of harming the competitiveness of U.S. firms.

Introduction

In December of 2017, Congress passed the most sweeping set of changes to the federal tax code since 1986. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) broadly reformed three major elements of the federal tax code: the individual income tax, the corporation income tax, and the tax treatment of international income. The third set of reforms moved the U.S. international tax regime to a nominally territorial system, but this change required a new set of rules to prevent the erosion of the U.S. tax base.

The GILTI, or “Global Intangible Low-Taxed Income,” provision is one of these new base-erosion rules. It essentially established a minimum tax for business income with certain characteristics. The GILTI provision was designed to target high-return, highly mobile income that could otherwise avoid tax, such as patent income. The GILTI provision, however, may also ensnare firms and income beyond the intention of policymakers, unduly harming U.S. economic interests.

What Is GILTI?

A key element of the TCJA, and of many previous tax-reform plans, was to modernize the way the federal government taxes income earned overseas by U.S. firms. Prior to the TCJA, the United States imposed a worldwide tax, which subjected U.S. firms operating abroad to U.S. taxes on their overseas profits, although foreign subsidiaries of U.S. firms could defer those taxes by keeping their related earnings overseas, known as deferral. The old system, particularly when paired with one of the highest corporate tax rates in the world, had a number of drawbacks, not least of which was the incentive for U.S. firms to “invert” and move their headquarters overseas.[1]

The TCJA contained a number of provisions that upended the old system, including replacing the worldwide tax system with a territorial system whereby the foreign-sourced income of U.S. firms would be exempt from taxation. In so doing, the United States joined 29 of the 34 economies in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) that have adopted some form of a territorial system.[2] Notwithstanding the deficiencies of the prior U.S. international tax regime and the global trend toward territorial tax systems, territorial systems are not without their own complications. Territorial systems require complex rules to establish guardrails around a nation’s tax base – in a territorial system, tax planners have every incentive to shift profits into low-tax foreign jurisdictions. [3] These types of rule, known as “base erosion” provisions, are designed to mitigate the incentives for taxpayers (think large multinational firms) to shift income abroad to avoid U.S. taxes. Accordingly, the international provisions of the TCJA introduced a series of new rules (and acronyms) to tax policy, including the “base erosion and anti-abuse tax” (BEAT), the Foreign Derived Intangible Income (FDII), and GILTI. While each provision was designed to operate in coordination with other international elements and the TCJA more broadly, this primer specifically examines the GILTI provision.

Upon enactment, the TCJA added section 951A to the federal tax code, which states (emphasis added): “Each person who is a United States shareholder of any controlled foreign corporation for any taxable year of such United States shareholder shall include in gross income such shareholder’s global intangible low-taxed income for such taxable year.” Section 951A thereafter defines the concepts, formulas, and rules for taxpayers to determine their tax liability for this newly defined form of income.

At its most basic level, the provision defines GILTI income as the amount of income earned by a U.S. foreign subsidiary above a certain threshold amount. The threshold amount is 10 percent of a foreign subsidiary’s qualified business asset investment (QBAI). QBAI is essentially the tangible assets – such as machines and other equipment – of the foreign subsidiary inclusive of depreciation. The rationale for this standard is that 10 percent represents a reasonable rate of return on a firm’s tangible assets. GILTI income is the excess income above that rate of return. Thus, while the provision nominally targets income on intangible assets overseas, it really targets any income that can be defined as “excessive” measured relative to a foreign subsidiary’s tangible assets.

The archetypal example to illustrate how the GILTI tax works is the income earned by a global technology company’s patents that are stashed in a filing cabinet in an office in a low-tax country. That firm would have every incentive to minimize its tax liability on those profits (within the law). Targeting that income for tax is difficult, but in this instance, the design of the GILTI provision isolates the income earned from these intangible assets – which is well above the 10 percent return on a filing cabinet!

Determining GILTI Tax Liability

Taxpayers with GILTI face U.S. taxation that would otherwise be applied at the new statutory corporate tax rate of 21 percent. The law’s structure curtails the impact of this provision, however: Through 2025, taxpayers may claim a deduction equal to the amount of 50 percent of GILTI, and 37.5 percent thereafter. Accordingly, taxpayers reporting GILTI income face effective U.S. tax rates on that income of 10.5 percent through 2025 and 13.125 percent thereafter. These deductions are limited under certain circumstances.[4]

To the extent that GILTI is earned overseas, U.S. foreign subsidiaries may have paid foreign tax on that income. Consistent with other elements of the TCJA and prior tax law, taxpayers may claim credits against foreign taxes paid, but the TCJA limits foreign-tax credits (FTC) against GILTI income to 80 percent of taxes paid. This limitation has the effect of increasing the effective tax rate that firms face compared to if they could claim credits for all of their paid foreign taxes.

GILTI By Example

To illustrate how GILTI works, consider the hypothetical technology firm noted above. For the purposes of this example, assume the parent firm is U.S. based and is the sole shareholder of a subsidiary operating out of a foreign country that has a 10 percent tax rate. For this example, assume the subsidiary is essentially earning income ($100 in this example) from patents ascribed to its foreign subsidiary with $100 in tangible assets (essentially the office equipment). In this case, the excess over the 10 percent return on $100 in office equipment would equal the GILTI amount that the parent firm would need to report on its tax return.

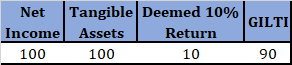

Table 1. Hypothetical Firm’s GILTI Income

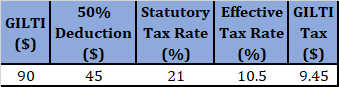

The parent technology company would then report this income on its U.S. tax return. It would claim a 50 percent deduction against its reported GILTI ($45), and face a 21 percent rate on the remaining balance, for an initial GILTI tax liability of $9.45.

Table 2. Hypothetical Firm’s Initial Tax Liability

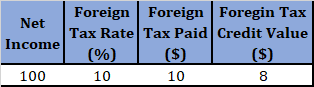

Note that this example assumes the firm paid 10 percent tax on its income to its foreign host. In this simple example, assume that the firm paid 10 percent tax to its foreign host on its $100 in net income, for $10 in taxes paid. However, it would only be eligible to claim a credit equal to 80 percent of those taxes paid ($8) to its foreign host.[5]

Table 3. Hypothetical Firm’s Foreign Tax Credit Value

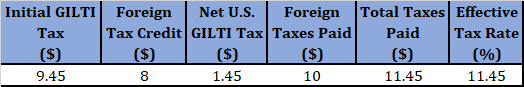

In this circumstance, the U.S. firm would face U.S. tax on its GILTI income of $1.45, in addition to the taxes owed to the foreign host. In total, the U.S. parent will have paid $11.45 in taxes on its GILTI income – $10 to its foreign host and $1.45 to the United States for an effective tax rate of 11.45 percent.

Table 4. Hypothetical Firm’s GILTI Tax Liability

Note the effect of the 80 percent FTC limitation, which essentially raises the effective tax rate borne by this firm under this provision. If the host country imposed no tax, the rate would decline to 10.5 percent, because the value of the limitation on the FTC (the 20 percent difference between the 80 percent limitation and the full value of taxes paid to the foreign host) would be zero. However, the higher the tax paid to foreign nations, the more valuable (or costly from the firms’ perspective) that limitation becomes.

Other Possible Consequences of GILTI

The preceding example is comically simple compared to the reality of global commerce, supply chains, and the wisdom of tax planners, and does not fully explain every dimension of the GILTI provision. GILTI interacts with other major elements of the tax code, the unique circumstances of every affected taxpayer, and the tax policies of foreign governments. It should not surprise that such a multi-faceted reform effort will require further refinement through the regulatory process and possibly even future legislation.

As U.S. firms come to terms with the new U.S. tax system, some firms are reportedly facing unanticipated tax liabilities under GILTI that may not have been the intention of Congress. The most conspicuous example is from Tupperware, which reported in its Securities and Exchange Commission filing for the first quarter of 2018 that its effective tax rate rose to 38.8 percent from 26.2 percent in 2017 because of GILTI. Specifically, Tupperware noted, “The effective tax rate for the first quarters of 2018 and 2017 were 38.8 percent and 26.2 percent, respectively. The change in the rate was primarily due to the estimated impact of Global Intangible Low-taxed Income (GILTI) under the newly enacted Tax Cuts and Jobs Act. The Company continues to evaluate the impact of the GILTI provisions under the Tax Act which are complex and subject to continuing regulatory interpretation by the U.S. Internal Revenue Service .”[6] Tupperware has since revised downward its tax liabilities, but the company remains illustrative of the potential for GILTI to increase effective tax rates.

Despite the name, the GILTI provision does not just capture income from intangible assets. It may indeed apply to any income above the deemed return threshold. A heavy manufacturing plant earning income on fully depreciated assets overseas is treated the same as the filing cabinet tech subsidiary under GILTI. There is also uncertainty as to the availability of even the restricted (80 percent) foreign tax credit to offset U.S. GILTI tax liability.

The Treasury Department is reportedly close to issuing needed rules to clarify the tax treatment of this newly defined type of income and that will provide greater certainty to U.S. firms operating under this new tax regime.

Conclusion

The TCJA was a somewhat conventional, if broad, tax reform measure, with tax cuts tending to outweigh the reforms. The international tax reforms, however, mark a radical departure from past U.S. practice and broadly reflect the evolution of tax policy among major world economies. As part of this reform effort, new rules were needed to preclude the erosion of the tax base, rules that include the GILTI provision. The GILTI provision is one manifestation of the type of guardrail that must be paired with a territorial system. As a new and complex policy, the GILTI provision will likely require regulatory and possibly future legislative refinement to ensure it achieves the intent of Congress to enhance the competitiveness of U.S. firms abroad, while preserving the integrity of the U.S. tax base.

[1] https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/cost-inaction-tax-reform/

[2] https://taxfoundation.org/territorial-tax-system-oecd-review/

[3] See https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/The%20International%20Tax%20Bipartisan%20Tax%20Working%20Group%20Report.pdf and https://www.jct.gov/publications.html?func=startdown&id=4656

[4] Specifically, if a taxpayer reports that GILTI income and FDII income exceed a firm’s total income in a given year. For more on FDII income see: https://home.kpmg.com/content/dam/kpmg/us/pdf/2018/02/tnf-new-law-book-feb6-2018.pdf

[5] To calculate foreign taxes paid on GILTI income, firms must determine their “inclusion percentage,” which the percentage of a U.S. firm’s aggregate GILTI income as a share of its net income (specifically “tested income”), multiplied by total foreign taxes paid. See: https://www.davispolk.com/files/2017-12-20_gop_tax_cuts_jobs_act_preview_new_tax_regime.pdf

[6] https://www.sec.gov/Archives/edgar/data/1008654/000100865418000012/tup10q033118.htm