Insight

May 23, 2023

Inflation Reduction Act: UK Case Study of Drug Pricing Limitations

Executive Summary

- The Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) mandate that drug manufacturers pay a certain price concession (rebate) may have the unintended consequence of driving some manufacturers out of the market—a real possibility in the United Kingdom—potentially reducing access to medicines for patients.

- To avoid the regulatory burden of the IRA, drug manufacturers are also likely to revise their research and development strategies as government reimbursement from Medicare may not be viable for certain products or medical conditions.

- Lawmakers should examine the impacts of other countries’ drug negotiation and rebate strategies to avoid establishing a process that could lead to drug shortages or delays of new therapies.

Introduction

The Inflation Reduction Act’s (IRA) mandate that drug manufacturers pay a certain price concession (rebate) may have the unintended consequence of driving some manufacturers out of the market—a real possibility in the United Kingdom—potentially reducing access to medicines for patients.

To avoid the regulatory burden of the IRA, drug manufacturers are also likely to revise their research and development strategies as government reimbursement from Medicare may not be viable for certain products or medical conditions.

As U.S. policymakers consider amending the framework of the IRA to include additional drugs in Medicare Part D and Part B, it is worthwhile to understand the ways in which other countries pay for drugs. Although the United Kingdom (UK) has a single-payer system, the UK government has sought to provide new innovative therapies (such as CAR-T) and medicines for cancer[1] while fostering a collaborative relationship with drug manufacturers. The U.S. population covered by Medicare is similar in size to the UK population (approximately 65 million compared to 67 million, respectively)[2]. Furthermore, the UK was consistently in the top three G20 countries for new medicines to come to market in 2012–2021 as determined by the Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers.

The UK has two regulatory schemes, statutory and voluntary, each of which sets certain price concession methodologies for drug manufacturers to participate in the market and receive government reimbursement for their products.[3] A drug manufacturer can only operate under one scheme. The voluntary scheme, which was updated in the UK in 2019, allowed drug manufacturers more flexibility and better contracted terms than the traditional statutory scheme.[4]

Of note, The National Health Service (NHS), alongside the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) which acts on behalf of the governments of the UK, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, works with industry to negotiate price concessions (also known as rebates or inflationary penalties) at a set percentage to control government spending on branded medicines.[5] Patients in England pay for their prescriptions, which are currently set at a flat price of £9.65 per item (or approximately $12.00 U.S. dollars).[6]

In December 2022, the UK government announced that, starting in 2024, drug manufacturers participating in the country’s voluntary scheme must pay a price concession of 26.5 percent for sales of drugs that typically exceed 2 percent of sales growth per year. This payback price concession is almost double the amount drug manufacturers paid in 2022. This change in the voluntary scheme’s price concession has prompted several large drug manufacturers to threaten to reduce their participation in the UK market for medicines.

To avoid a similar situation in the United States, policymakers would be wise to examine the problems surrounding the new UK drug rebate proposal to avoid establishing a process that could lead to drug shortages or delays of new therapies.

In April 2023, leading Republican members of Congress authored a letter to Health and Human Services Secretary Xavier Becerra and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Administrator Chiquita Brooks-LaSure related to CMS’ initial guidance on implementing the IRA. Last month, the White House released a list of Part B drugs subject to the new law. Examining how drug manufacturers have responded to the UK government’s recent changes in its voluntary scheme for drug rebates will provide insight into the pitfalls of setting high rebated amounts. Moreover, policymakers should be aware of potential consequences the IRA could have if CMS took a similar approach.[7]

The American Action Forum (AAF) has covered the ongoing U.S. drug shortage as well as the health care provisions in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). See AAF’s insight on pricing methodology in Medicare Part B and Part D under the IRA for more information.

Case Study: UK Rebate Scheme

The National Health Service (NHS) is funded in the UK primarily through general taxation and residents are entitled to free health care at the point of service. While the UK government’s management of its health care system varies in many ways from that of the United States, it is nevertheless a useful example of how government reforms to increase certain rebated amounts may exceed the drug manufacturers’ ability (or willingness) to meet these financial expectations.

The UK has different laws[8] governing the procurement of prescription drugs than does the United States but it faces similar challenges related to reimbursement for certain generics, as these prices are negotiated by the UK government for all patients.[9] Currently, the UK Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) can fast track applications for medicines in case of a public health emergency or when essential medicines are in short supply.[10]

DHSC released a proposal to increase in 2023 the payment percentage for the statutory scheme for branded medicines. The scheme works by restricting the “growth in allowed sales of branded medicines.”[11] Drug manufacturers are subject to the statutory scheme unless they opt into the 2019 Voluntary Scheme for Branded Medicines Pricing and Access (VPAS).[12] Drug manufacturers often join the VPAS scheme as they benefit from lower rebates than the statutory scheme and receive certain exemptions. Moreover, VPAS is a non-contractual agreement negotiated between UK agencies and the pharmaceutical industry. The current VPAS will conclude at the end of 2023.

Of note, the COVID-19 pandemic put pressure on the NHS to secure certain drugs and therapies for patients, which forced drug manufacturers to exceed the allowed growth rate. As a result, those manufacturers participating in VPAS are now expected to pay a larger payback price concession of 26.5 percent, similar to the statutory scheme, for which the government has set at 27.5 percent price concession for 2023, an increase from 24.4 percent in 2022. In other words, manufacturers had provided some products at a loss.[13]

The voluntary scheme is an agreement between the UK government agencies and the pharmaceutical industry that spending by the NHS on branded medicines will stay within an agreed limit, set at 2 percent per annum for 2018–2023. If a drug manufacturer’s sales exceed this amount, it must pay the UK government back monies that surpassed the allowed growth rate.

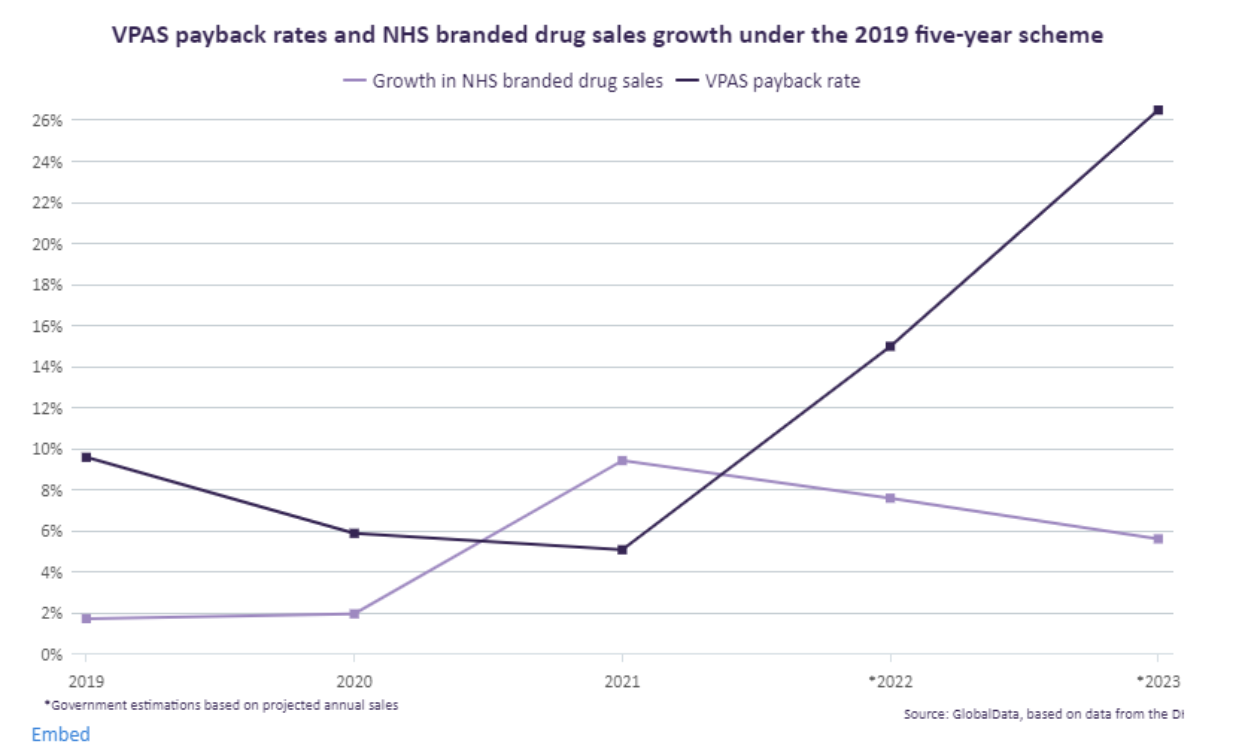

The above graph shows, payment percentages paid through the voluntary scheme for 2019–2021 were under 10 percent.[15] The COVID-19 pandemic and subsequent surges for products following lockdowns led to a 15 percent rebate for 2022.[16] The UK government’s current proposed increase of 26.5 percent is estimated to be approximately £3.3 billion (approximately $4.10 billion in U.S. dollars) in sales revenue.[17]

A recent report found that the “increased government revenue from raising the rebate rate over the VPAS is more than offset by higher prices and costs for the NHS and has other longer-term implications due to continuity of supply.” Tellingly, the Telegraph reported that Eli Lilly and AbbVie left VPAS in January 2023. In fact, a study found that VPAS “could actually reduce generic and biosimilar competition to such an extent that prices rise for the NHS.”[18] Managing reimbursement for drugs remains a challenge as some manufacturers may exit the UK market due to high rebates. In turn, the UK government could face significant increases for pharmaceutical products at risk of shortage.[19]

Conclusion

U.S policymakers should examine how the UK sets price concessions for drug manufacturers to avoid establishing a process through CMS that could lead to increased drug prices, drug shortages, or delays of new therapies. Industry participation is key to avoiding policies that could increase drug shortages or reduce investments in new medicines due to long-term reimbursement concerns. Moreover, reducing the price of a single drug should not be seen as the only mechanism to limit government spending.

[1] National Health Service England Cancer Drugs Fund Team “Appraisal and Funding of Cancer Drugs from July 2016 (including the new Cancer Drugs Fund) A new deal for patients, taxpayers and industry” 2016. The authors explain that “The Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF) was established by the Government in April 2011 as a temporary solution to support clinicians and their patients gain access to cancer drugs not routinely available on the NHS. The Fund was originally due to end in 2014, having acted as a bridge to a new system of Value Based Pricing.”

[2] According to the Congressional Research Service for 2021 “approximately 299 million had private health insurance (group and non-group), 60 million Medicare coverage, 69 million Medicaid/CHIP coverage, 16 million Military coverage (TRICARE and VA Care) with 28 million uninsured).” The author does note that the Medicare population is mostly for individuals over 65 and the UK whole population covers an entire population regardless of age.

[3] Please see NHS Act 2006 for additional information on the authority the UK government has to set terms within the voluntary scheme.

[4] Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry “Voluntary Scheme on branded medicines.” ABPI explains that “The last Voluntary Scheme, known as the 2014 PPRS, came to end on 31st December 2018 and was replaced by the 2019 VPAS. Voluntary Schemes are designed to strike a balance between supporting innovation in the pharmaceutical industry and ensuring medicine spending in the UK remains under control. Companies that do not join the Voluntary Scheme are subject to what is known as a Statutory Scheme. The voluntary approach arguably explains how the UK has historically reconciled only modest expenditure on medicines with life sciences investment levels that have remained substantial.”

[5] Leela Barham, “Where do VPAS rebates go?” Pharmaphorum, March 2023. Barham explained that “Each of the four nations use the monies generated by rebates to fund different activities. For example, NHS England uses the money to support general funding as compared to Scotland which used the rebated monies to fund new medicines.”

[6] Institute for Government “Devolution and the NHS” 2020. According to the Institute “After devolution Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland all abolished prescription charges, making England the only of the four nations in which patients pay for prescriptions. In 2018/19, £576 million was raised through the prescription charge, which accounts for 0.5% of the NHS England budget.”

[7] U.S. Government Accountability Office “Prescription Drug Spending” 2017. The report found that “Federal programs may pay different prices for the same drug. For example, Veteran’s Affairs (VA) paid, on average, 54 percent less per unit for a sample of 399 brand-name and generic prescription drugs in 2017 than Medicare Part D (even after accounting for rebates and price concessions in the Part D program). This may partly be due to VA’s access to certain discounts (which are defined by law) that are not available to Medicare Part D plans. But giving such discounts to all federal programs may not produce a net benefit. If a large federal program with many beneficiaries became eligible for the discounts available to other programs, manufacturers might choose to raise prices for these other programs to offset the discounts.”

[8] Please see Medicines & Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, “The Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency regulates medicines, medical devices and blood components for transfusion in the UK. MHRA is an executive agency, sponsored by the Department of Health and Social Care.”

[9] The U.S. does require, by statute, certain drug pricing concessions for manufacturers to participate in the Medicaid program and other federal programs including participation in the 340B drug pricing program. The Congress Research Service (CRS) found that 340B sales are approximately 7.2 percent of the US drug market. Although drug manufactures are required to sell these products at a discount (estimated to be between 20-50%) to assist low-income patients, in practice many of the covered entities purchasing these drugs at a discount are able to make a profit from commercially insured individuals paying a higher level of reimbursement than cost of purchasing the discounted drug. In terms of Medicaid drug manufacturers are required to offer the program “the lowest price available from the manufacturer during the rebate period to any wholesaler, retailer, provider, health maintenance organization, nonprofit entity, or governmental entity within the United States.” The Centers for Medicare &Medicaid Services (CMS) released new guidance on Medicaid Best Price guidance. The Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) provides HHS the authority to negotiate prices for Medicare Part D for a set number of specific drugs. Under the IRA, manufacturers will face an inflationary rebate if they raise their prices faster than inflation for Medicare Part B. As the US drug marketplace has many different types of payers, drug shortages can be mitigated by commercial reimbursement rates as compared to reimbursement solely by Medicare, Medicaid or other government purchasers such as the US Department of Veterans Affairs.

[10] DHSC via the Price Service Negotiation Committee will allow for higher price concessions for certain products at risk. According to PSNC “When community pharmacies cannot source a drug at or below the reimbursement price as set out in the Drug Tariff, (DHSC) can introduce a concessionary price at the request of PSNC.” In a nutshell, a price concession means that DHSC will pay a higher amount for a product for the month the product was approved. Academic Researchers at Oxford University have projected that over the last twelve months an additional spend of £312,130,000.

[11] The Branded Health Service Medicines (Costs) Regulations 2018

[12] Before VPAS, Pharmaceutical Pricing Regulation Scheme (PPRS) was in place until the end of 2018.

[13] Hugh Kent-Egan “VPAS: One-off repayment rate for 2022 announced” Bristow. Egan explains that “However, there was exceptional growth in the sale of branded medicines in 2021, stemming in part from demand related to the COVID-19 pandemic, with the total measured sales growth jumping to over 9% significantly in excess of the allowed growth rate of 2% set out in the scheme. As a result the 2022 payment percentage was predicted to jump dramatically to 19.1%. This generated consternation as margins are very tight for many of these products, with some being supplied at cost to the NHS, and a hike in repayments would mean that companies tied to NHS tenders or long term agreements may even be supplying products at a net loss.”

[14] Janet Beal “Pharma sector reels as UK Government doubles VPAS payback rate on NHS drugs” Pharmaceutical Technology.

[15] Bukkly Balogun, Elizabeth Rough, Nikki Sutherland “Debate on the voluntary scheme for branded medicines and the life sciences visions” House of Commons Debate Pack May 2, 2023. The authors note that the payback price concession amounts were: 15 percent in 2022, 5.1 percent in 2021, 5.9 percent in 2020 and 9.6 percent in 2019.

[16] This percentage was set by an amendment reducing it from 19.1 percent. The difference in this amount was expected to be captured in the rate set for 2023—yet the 26.5 percent was higher than anticipated by industry.

[17] Emily Kimber “AbbVie and Eli Lilly leave UK’s voluntary drug pricing agreement” PM Live. Kimber adds that “In December, the government announced that those within the voluntary scheme would be required to return almost £3.3bn in sales revenue – 26.5% of sales – up from around £0.6bn in 2021 and £1.8bn in 2022. Speaking about the levy, Todd Manning, general manager UK, AbbVie said: “Levy rates close to 27% of revenue are not seen in any comparable country and they have a demonstrable impact on our ability to operate sustainably in the UK.”

[18] Sarah Neville, “Drug Companies Warn UK over ‘penalizing rebate’” Financial Times, 2022. The Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry (ABPI) recently released their vision of an updated VPAS framework. ABPI stated that “As recently as 2021 the VPAS rebate meant companies paid around 5% of their revenue back to the NHS. But in 2022 it rose to 15% and in 2023 to 26.5%. This is completely outside both historical and international norms…”

[19] Industry has suggested a flat rebate of 6.88 percent to be levied across all eligible sales.