Insight

April 9, 2025

Lawmakers Have Little to Gain from Altering Taxation of Carried Interest

Executive Summary

- The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA) made a series of business tax reforms to boost U.S. competitiveness and economic growth, spur job creation, and increase incomes – and the results show the TCJA’s business reforms worked.

- As policymakers debate how to make the TCJA permanent, they should consider building on the success of the law’s business tax reforms with additional ones aimed at enhanced fairness, greater simplicity, and rapid economic growth; they should avoid reforms that undermine U.S. competitiveness and go against the key principles of good tax policy: fairness and efficiency.

- Policymakers have recently proposed changing the tax treatment of carried interest as part of a broader tax reform package; this insight explains how such a policy change would undermine U.S. competitiveness and fail to adhere to the principles of fairness and efficiency.

Introduction

Policymakers are currently debating how to make permanent many provisions of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act of 2017 (TCJA). Most of the TCJA’s individual income tax reforms are scheduled to sunset on December 31, 2025, while some of its business tax provisions will phase out or become less generous. While this is a top priority, policymakers are also considering other tax reforms to include in a legislative package. One policy change that’s been proposed is to reform the tax treatment of carried interest.

The TCJA marked a return to real fairness and efficiency in federal taxation. Not only did it streamline the tax code and make it easier for individuals and businesses to file their tax returns, but it also focused on U.S. competitiveness and economic growth to spur job creation and put more money in Americans’ pockets. The results show that the TCJA worked, especially on the business side. The United States hasn’t lost a single multinational corporate headquarters, applications for new businesses have soared, year-over-year growth in real gross domestic product accelerated, and real nonresidential fixed investment grew.

This year’s tax reform should aim not just to extend the TCJA, but to build on its success. Specifically, policymakers should consider additional business tax reforms that enhance incentives to invest, innovate, and allocate capital efficiently. Any reforms should focus on boosting U.S. competitiveness and adhere to the key principles of good tax policy: fairness and efficiency.

This insight explains how changing the tax treatment of carried interest would undermine U.S. competitiveness and violate the principles of fairness and efficiency.

A Push to Change the Tax Treatment of Carried Interest

One policy proposal getting attention is reforming the tax treatment of carried interest from a long-term capital gain to ordinary income. It was recently reported that President Trump wants to eliminate the capital gains tax treatment of carried interest. At the same time, Democrats in both the House and Senate have introduced legislation to tax carried interest as ordinary income. These developments have re-ignited a long-standing debate over the fairness and economic impact of the taxation of carried interest under current law.

Carried interest is an integral feature of the financial arrangements of partnerships. It’s a management structure used in the United States, typically in the finance, oil and gas, and commercial real estate sectors. Under this arrangement, the general partners in a partnership invest money and expertise in the business and in return receive a portion of the profits beyond the capital they invest. This business model permits entrepreneurs to match their expertise with a financial partner, assume risks, and align the parties’ economic interests.

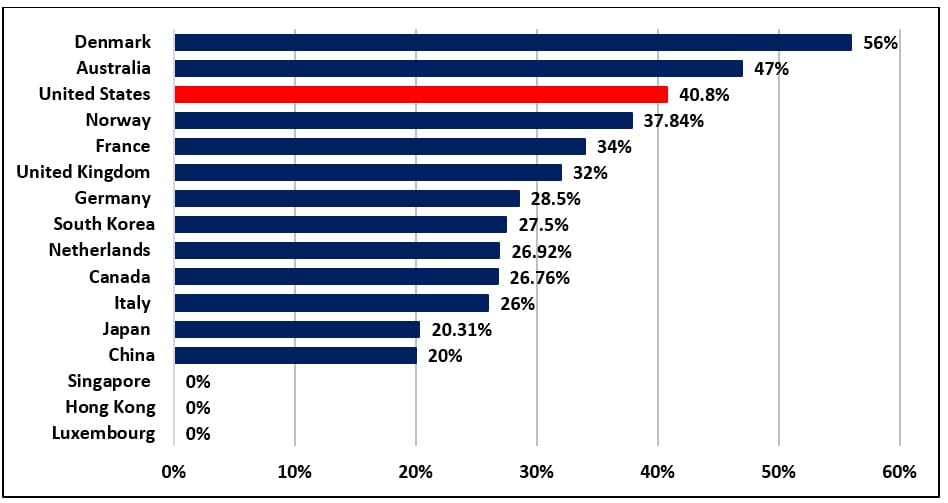

Carried interest is currently taxed upon the sale of the partnership’s real assets as a long-term capital gain at a maximum rate of 23.8 percent (inclusive of the 20 percent maximum long-term capital gains rate and the 3.8 percent Net Investment Income Tax (NIIT)). The proposal to tax it as ordinary income would increase the maximum rate to 40.8 percent (inclusive of the 37 percent top individual income tax rate and the 3.8 percent NIIT) – a 17-percentage point (71 percent) increase. Such a proposal would erode U.S. competitiveness, especially compared to major competitors that do not tax carried interest at higher income tax rates. Under the policy change, the rate would be more than double that of China and Japan and over two-fifths larger than Germany. This would be a step back from the TCJA, which boosted U.S. competitiveness primarily by lowering the corporate income tax rate from 35 percent to 21 percent, made the United States a more attractive destination for business investment, and reduced incentives for companies to shift their headquarters and profits overseas.

Moreover, taxing carried interest as ordinary income would do little to improve the nation’s fiscal outlook. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the proposal would generate $13 billion of revenue over 10 years – a small drop in the bucket compared to the nearly $26 trillion of budget deficits projected over the next decade. Even as an offset for the reconciliation legislation being negotiated, it’s still a drop in the bucket. Thirteen billion dollars is about one-fifth of a percentage point of the $5.8 trillion new borrowing that could be enacted through reconciliation.

Principles of Tax Policy and Carried Interest

Advocates of taxing carried interest argue that doing so would increase fairness, claiming that it is unfair to single out carried interest for preferential tax treatment. In their view, this exemption provides a particular form of general partner compensation with preferential tax treatment. They argue that the general partner is providing services to the partnership, and services are taxable as ordinary income. Thus, they claim, a “carried interest loophole” exists.

But carried interest isn’t singled out for preferential tax treatment – it’s among the many items treated as a long-term capital gain and taxed accordingly at a maximum rate of 23.8 percent. From an equity perspective, there’s an unfairness inherent in the proposal in that it would cause similar taxpayers to be taxed differently. If enacted, investments in real assets would face different effective tax rates depending upon whether they are undertaken by an individual, C corporation, or via the limited partnership structure.

What’s more, carried interest is not the same as other compensation. The carried interest is a share of partnership profits and not considered compensation for services by the partners – management and other annual fees constitute such compensation. These non-insubstantial fees are taxed as ordinary income. They are based on the entire amount of partnership capital under management and paid annually by the partnership. The management fee is typically 2 percent of the capital under management but can also include other fees such as acquisition, development and leasing fees. If a partnership underperforms, a management fee is the only income the general partner receives. Simply stating that the carried interest is compensation for services ignores the economic relationship of the partners in the partnership.

The tax change is potentially unfair from a third perspective as current proposals are not exclusively changes in the prospective treatment of carried interest. That is, they do not rule out retroactive tax increases on investments undertaken, assuming that carried interests would be characterized as capital gains for tax purposes.

From an efficiency perspective, treating carried interest as ordinary income would not improve the U.S. tax code. First, differential taxation of capital income across sectors and business forms introduces inefficiencies in the allocation of national wealth.

Second, the proposed treatment is inconsistent with both income tax principles and consumption tax principles. On the latter, there is a wide consensus that U.S. fiscal policy must promote the most sustainable pace of long-term economic growth. Integral to this is keeping taxes on the return to savings, investment, and entrepreneurial innovation as low as possible. Pro-growth tax reforms that focus on taxing consumption typically permit a full deduction from the tax base for all capital contributions to investments as the appropriate offset for taxing the future cash flow returns at a full rate. The proposed tax change on carried interest imposes the latter taxation, without the corresponding deduction and is thus inconsistent with a consumption tax base.

From the perspective of tax policy, such a policy change is neither a genuine move toward more fairness in the current tax system nor a movement of the current system toward an optimal overall tax code.

The Likely Outcome of Higher Carried Interest Taxation

If the policy change were implemented, partnerships may restructure in response to the new, higher level of taxation. More time and capital would be spent by limited and general partners to restructure their investment vehicles so the overall impact of the reformed taxation on carried interest can be minimized or avoided altogether.

By definition, these new partnership structures would be inferior to the original, as this outlay and use of time would not improve economic performance overall or contribute to investment managers’ objectives, their institutional investors, and their individual clients. If possible, the general partners would have an incentive to pass these higher costs to the institutional investors and individual clients, thus reducing their rate of return.

A related avenue of adjustment would be to replace the incentive-based carried-interest structure between general partners and their investors with non-contingent, fixed compensation arrangements. Due to the absence of performance incentives, these types of compensation contracts would not produce superior investment performance, with a resulting decline in return on investment. Moreover, depending on the nature of these arrangements, they may raise little revenue as the taxed compensation to the general partners would be deductible to individual and corporate investors. It is also unlikely that legal adjustments alone would be sufficient to avoid the entire tax. If so, real economic activity would be affected. Placing a greater tax burden on carried interest would raise the overall tax burden on the investment. Unless the project is sufficiently profitable, it would not be possible to pay annual operating expenses, cover the depreciation of property, meet contractual obligations for debt financings, pay taxes, and offer a competitive return to the equity partners in the investment.

In such circumstances, the projects that don’t make the cut would be dropped – projects, in particular, that are likely to be located in more marginal locations or burdened with greater risk. In modern, competitive global financial markets, even small changes in margins move trillions of dollars of financial capital; the taxed partnerships would be at a clear financial disadvantage and would lose capital to other investment opportunities.

The shifting of capital from one sector of the economy to another in response to higher taxes has been heavily scrutinized in the context of the corporate income tax. The corporate income tax is a tax on the return to capital that is received through a particular business structure, the C corporation. Increasing taxes on carried interest by taxing it as ordinary income is a tax on the return to capital that is received through a particular business structure, the partnership.

While the legal setting is different, the economics are the same. One dimension to the cost of the discriminatory taxation of carried interest is that capital would be shifted to less productive uses, thus damaging overall economic performance. For example, imagine there is no tax – that is, there is equal tax treatment – across all uses of capital, and all returns are equalized at a pre-tax return of 20 percent. Now, imagine that partnerships face a unique and higher tax rate of 50 percent. Immediately, the post-tax return would fall to 10 percent, which would be inferior to opportunities of 20-percent returns elsewhere and capital would flow to those opportunities.

The process would continue until post-tax rates of return equalize and eliminate incentives for capital shift. If pre-tax returns in the taxed sector are 30 percent and those in the less-taxed sector are 15 percent, the post-tax return would be 15 percent in both. The tax, however, generates a clear cost to the economy: Capital is twice as productive (30 percent versus 15 percent) in the taxed sector as elsewhere. By driving capital from more productive to less productive activities, the tax reduces overall productivity of capital and shrinks the economy.

Higher Carried Interest Taxation Would Dampen Entrepreneurial Talent

When taxes increase, they drive away the key element of economic success: entrepreneurial talent. Taxed and untaxed business structures compete for the same entrepreneurial management talent and produce the same ultimate product: investment services. Higher taxes on carried interest would diminish not only the ability to attract capital but also the same quality of managerial talent to make the capital productive in partnerships.

The prospect of lower after-tax pay would lead prospective investment managers to examine other employment opportunities in the market. The lower quality of management would ultimately diminish performance.

This suggests that the economic costs of crowding out partnership projects plus the lower performance that comes from diminished entrepreneurial talent would impair the economy as a whole. These economic costs represent foregone income in the economy.

Conclusion

There is little to gain from reforming the taxation of carried interest. It would reduce U.S. competitiveness, raise a minimal amount of revenue, and inflict significant damage on the affected areas of the business sector. It would effectively represent a step backward from the success of the business tax reforms in the TCJA. As policymakers debate how to make the TCJA permanent, they should consider building on the law’s business tax reforms with additional ones aimed at enhanced fairness, greater simplicity, and rapid economic growth – and not reforms that would undermine U.S. competitiveness and erode the key principles of good tax policy: fairness and efficiency.