Insight

June 29, 2023

Reviewing Proposed FISA Reforms

Executive Summary

- Title VII of the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act is set to expire on December 31, 2023, requiring Congress to reauthorize the legislation, including the contentious provision that allows for the collection of the electronic communications of foreign nationals on foreign soil without a judicial warrant.

- A bipartisan group of lawmakers is calling for significant reforms to Title VII intended to bolster oversight, privacy, and civil liberties protections for U.S. persons whose communications with foreign nationals may be intercepted.

- This primer explains the purpose of Title VII, why there is a push to reform it, and the delicate balance between protecting national security and upholding Americans’ civil liberties that lawmakers must consider.

Introduction

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act (FISA) Title VII, a vital component of the United States’ national security authority, is set to expire on December 31, 2023, without congressional reauthorization. With bipartisan support for a host of significant reforms and the deadline for reauthorization drawing closer, lawmakers have begun discussions on a path forward.

Proposed reforms focus on restricting the mass searching and collection of electronic records of U.S. persons, which is permitted without a warrant based on suspected foreign intelligence threats under Section 702 of Title VII. Despite continued efforts to reform Title VII over the past decade, there has yet to be any significant oversight or changes to the law. The last time Title VII was up for reauthorization in 2018, policymakers failed to agree on the type or scope of reform, resulting in a last-minute deal with few changes.

Given longstanding and frequently issued allegations of intelligence agencies’ abuse of their authority, members of Congress and advocacy groups propose reforms with more robust safeguards to protect U.S. persons, such as requiring the agencies to implement warrants and increasing congressional oversight of the intelligence community. Yet while lawmakers must consider reforms intended to better protect Americans’ rights, they must also consider their potential tradeoffs – namely, those that could unduly hamper the intelligence community’s ability to protect national security.

This primer explains the purpose of Title VII, why there is a push to reform it, and the delicate balance between protecting national security and upholding Americans’ civil liberties that lawmakers must consider.

FISA and Section 702 Overview

The Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA, enables U.S. intelligence services to conduct wide-reaching surveillance on foreign adversaries. FISA, enacted in 1978, codifies intelligence agencies’ powers to monitor foreign threats and provides oversight of the agencies’ actions against U.S. persons.

For programs authorized under Section 702, the National Security Agency (NSA) is responsible for collecting the emails and internet communications and can also query them, while the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), and other agencies can only query the data. FISA’s creation was most notably amended in 2008 to include Title VII, which codifies the authority provided to U.S. intelligence services over electronic and other surveillance tools for the digital age. FISA Title VII accounts for both domestic and foreign surveillance, expanding protections to the information of U.S. persons abroad.

Title VII contains a highly controversial provision, Section 702, that permits collection of foreign intelligence information from people reasonably believed to be outside the United States. The law has resulted in the incidental mass collection of U.S. persons’ electronic records without judicial warrants, raising numerous 4th Amendment and civil liberties concerns.

Under Section 702 authority, the federal government conducts a significant foreign intelligence campaign utilizing two intelligence gathering pipelines, upstream and downstream collection. Upstream surveillance is a process in which telecommunication companies, such as AT&T and Verizon, allow the NSA to copy all internet traffic that passes through the provider. The agency’s policy is to filter out domestic communications and record only communications of foreign nationals on foreign soil. Downstream surveillance refers to utilizing tech companies, such as Google or Meta, to turn over communications that involve a specific email address or phone number. These identifiers are required to be foreign in origin.

Both types of surveillance can incidentally capture communications between U.S. persons and foreign sources, making Section 702 a highly controversial provision. Critics view the potential capture of communications as a violation of 4th Amendment rights, specifically the unreasonable seizure of property without a warrant – including domestic emails, phone data, and messages. The process of searching this incidentally collected data is referred to as “backdoor searching,” the most controversial of Title VII programs.

Controversy and Calls for Reform

Ten years ago, Edward Snowden, a former computer intelligence consultant at the NSA, released information on the extent of the NSA’s mass surveillance programs, spurring the movement to reform FISA’s Title VII. The first attempts to broadly reform Title VII came in 2017, when a bipartisan group of senators introduced the USA Liberty Act. The bill attempted to overhaul the intelligence community’s authority, implementing changes to FISA court proceedings through increasing the presence of Amici, representatives appointed by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (FISC) judge to challenge the government’s interpretation of the law. Additionally, it required semiannual FBI reports and reporting and oversight programs. The majority of the USA Liberty Act’s provisions were not included in the FISA Amendments Reauthorization Act of 2017, the bill that eventually passed to reauthorize Title VII. Several additional reporting requirements were included, with no other changes implemented. The most controversial piece of Section 702 programs, backdoor searching, was left largely untouched.

As disclosures and reports have indicated further intelligence community abuses – and key members of both parties want changes – Congress appears less inclined to seek a “clean” reauthorization of Title VII. In relation to FISA Title VII, Senator Mike Lee (R-UT) said at a hearing with U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland, “You can tell your department, not a chance in hell we’re going to be reauthorizing that thing without some major, major reforms.” Senator Dick Durbin (D-IL), chair of the Senate Judiciary Committee, recently said during a hearing on Title VII reauthorization that he would only support reauthorization if there are “significant reforms,” and called to require warrants for searches of U.S. persons’ information.

Overall, Congress’ trust in the intelligence community has declined over the past few years. At the start of the 118th Congress, the House Judiciary Committee formed the Select Subcommittee on the Weaponization of the Federal Government, aimed at overseeing the FBI. A recently released FISC opinion revealed that the FBI conducted searches of 19,000 campaign donors, a U.S. congressman, journalists, and protesters. The report has generated significant press coverage, bolstering support for program reform. Recent developments have also led to numerous oversight hearings on the intelligence community.

Yet the intelligence community argues that Section 702 provides an efficient and effective tool for protecting Americans. All three agencies authorized to use 702 data (FBI, CIA, NSA) repeatedly utilize the tool, citing its usefulness in combatting terrorism, the fentanyl trade, and hostile cyber operations. Attorney General Garland testified at a Senate Judiciary Committee hearing that “we would be intentionally blinding ourselves” without 702. When considering proposed Title VII reforms, policymakers must consider the delicate balance between protecting national security and upholding Americans’ civil liberties.

Proposed Recommendations

The critical issue surrounding Section 702 is the search and collection of communications data, which could contain information belonging to U.S. persons, without a warrant. To address that concern, lawmakers and advocacy groups call for a warrant requirement to search information collected through Section 702 containing U.S. persons’ records. The intelligence community has historically opposed this requirement, claiming that “[a] warrant requirement would hamper the speed and efficiency of operations and impair the IC’s [intelligence community] ability to identify and prevent threats to America.” The intelligence community claims that U.S. person searches are targeted around identifying potential victims of cyber and terrorist attacks.

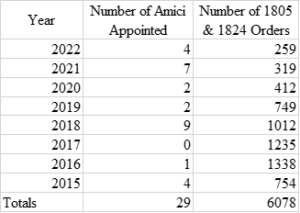

Another proposed reform focuses on the one-sided nature of FISC proceedings. The FISC provides judicial oversight of the FISA program and is intended to ensure that intelligence agencies comply with legislative requirements. A key component of the FISC is the process of having Amici during court hearings. Under current law, these counsels are selectively appointed by the FISC judge, with only 29 being appointed since 2015.[1] This represents 0.47 percent of all orders filed.

This lack of Amici appointees is due to the statutory scope of the program. Amici can only be appointed to cases that present a “novel or significant” reading of the law. Amici are also appointed by the FISC judges, who often lack incentive to disrupt the ex parte (meaning the government is the only party before the court) nature of the process. In 2020, the Senate passed the Lee-Leahy amendment, which expands the scope of the Amici program, encouraging representation in a majority of cases, not just the “novel or significant” ones. Additionally, the amendment empowered the Amici, giving them, for the first time, complete access to information regarding the case; this strengthens judicial accountability while protecting the classified nature of the FISC court system. In the most recent Senate Judiciary Hearing, Senator Lee continued to call for reforms to the court system, and it is likely that Congress will introduce similar amendments going forward.

FBI Deputy Director Paul Abbate updated the Senate Judiciary Committee on internal administrative changes made in response to concerns raised by Congress and civil liberties advocates. He testified that the FBI has implemented a “3 strikes” policy regarding FISA compliance for analysts working with data collected under Section 702. He also indicated that the FBI will evaluate field offices on their level of FISA compliance. The new policies are wholly internal without any external reporting or oversight processes. In response to these reported changes, Senator Lee raised the question: “Why should we trust the FBI and DOJ to police themselves?”

Conclusion

Given the perceived abuses of power within the intelligence community, there appears to be little interest on either side of the aisle to reauthorize FISA Title VII without significant reform. As the deadline for reauthorization draws near, policymakers must evaluate this controversial legislation that permits surveillance of foreign nationals without a warrant. Most likely, Title VII reform will focus on protecting Americans’ civil liberties while increasing judicial and congressional oversight of the program.

[1] https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2022rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2021rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2020rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2019rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2018rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2017rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2016rept-aousc.pdf

https://irp.fas.org/agency/doj/fisa/2015rept-aousc.pdf