Insight

February 26, 2025

Single-payer Health Care Wait Times: A Feature, Not a Bug

When debating the merits and pitfalls of single-payer health care systems, one oft-discussed sticking point centers on wait times. Patients in single-payer systems typically have significantly longer wait times for services than patients here in the United States. Why? In short, long wait times are a feature, not a bug, of single-payer systems.

The first and most obvious reason for this disparity in wait times is that single-payer systems often have fewer resources, such as MRI machines or orthopedic surgeons. For example, Canada has roughly half the number of orthopedic surgeons per capita compared to the United States – a critical shortage that Canadian professional societies have been calling out for more than 20 years.

An underrecognized reason for longer wait times, however, is that single-payer systems are designed to produce them as a means of reducing costs. In fact, they are designed to explicitly organize delays in care because it is the only way to make them work. As pointed out by the Hoover Institution:

Long waits are a defining characteristic of hyper-regulated single-payer systems as a means of cost containment, but they stand in stark contrast to US health care. Aside from organ transplants, “waiting lists are not a feature in the United States,” as stated by the OECD and verified by numerous studies.

Single-payer health care systems typically operate on a fixed budget. The government sets the total budget for the country’s health care and then allocates that money to certain locations and for certain services. Since there is typically more demand than money to provide those services, the government creates a system for rationing care. Of course, that requires the government to decide which health care is most important, creating competition for resources between different geographies, specialties, etc.

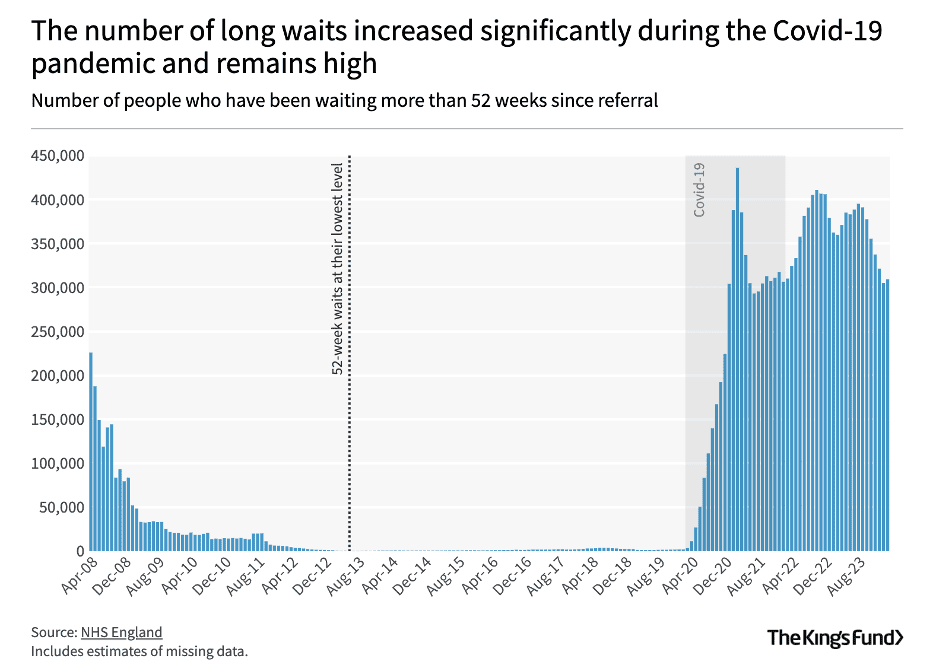

The unenviable but inevitable result is a waitlist. If the local hospital only has money allocated for 100 cataract surgeries but has demand for 200, then 100 people will need to go on a waitlist. These waitlist numbers worsen, of course, when there is an unusual demand for urgent services (such as during a pandemic) and other services must be put on hold. The UK’s National Health Service (NHS) illustrates this problem.

The UK National Health Service and Hospital Backlogs

In the United Kingdom’s hyper-regulated single-payer system, the NHS, hospital backlogs and long wait times for care are simply the reality patients must live with. Under the NHS’ constitution, 92 percent of individuals who are awaiting non-urgent, or elective, care are allowed to have wait times no longer than 4.5 months. Even this seemingly loose standard has not been met since 2015 – a decade ago – with performance declining steadily until the COVID-19 pandemic, when it “deteriorated rapidly.” The NHS’s wait times have not returned to promised levels. As of March 2024, the NHS’ wait list stood at approximately 7.4 million patients, consisting of around 6.3 million unique patients waiting for treatment. Of these more than 7 million patients, 3 million have been waiting beyond the 4.5-month standard, while more than 200,000 have been waiting for more than a year. NHS’ wait times have not returned to promised levels. As of March 2024, the NHS’ wait list stood at approximately 7.4 million patients, consisting of around 6.3 million unique patients waiting for treatment. Of these more than 7 million patients, 3 million have been waiting beyond the 4.5-month standard, while more than 200,000 have been waiting for more than a year. A January 2025 press release from The King’s Fund warned:

The NHS is facing a toxic cocktail of pressures this winter. Immediate issues such as long waiting lists and overcrowded hospitals have been made worse due to the poor weather and rising flu and respiratory conditions. And then there are a host of chronic long-term issues, including endemic staff shortages, deteriorating buildings and broken equipment, such as slow scanners, broken lifts and leaking roofs.

Over the past four years, UK medical-specialty services across the board have seen a fall in their performance, with not a single specialty meeting the required wait-time standard. Trauma and orthopedic specialties specifically had the highest number of patient waits, with more than 800,000 individuals (almost 54 percent) waiting longer than 4.5 months.

Long Wait Times Are a Feature, Not a Bug

In 2024, Canadian patients experienced a median wait time of 30 weeks between referral to their first treatment – up from 27.2 weeks in 2023. In rural areas, delays in care were lengthier, with waitlists for patients in New Brunswick and Prince Edward Island ranging from 69.4 weeks to 77.4 weeks. This appears to be taking a toll, as new polling shows that 38 percent of Canadians would pay out-of-pocket to travel to the United States to receive emergency care, while 42 percent would travel to the United States and pay for routine health care, if needed.

Bottom line: When access to care is controlled by a singular government entity that must balance both bureaucracy and budgets, lengthy wait times become a norm rather than an anomaly. As some U.S. policymakers consider the benefits of a single-payer system, it is critical they also understand the often-dramatic pitfalls.