Insight

November 19, 2021

The Biden WOTUS: Breadth and Uncertainty

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- The Biden Administration proposed a new definition of “waters of the United States” that can best be described as having the coverage of the Obama Administration’s 2015 rule with less certainty over which waters are covered.

- The proposal aims to thread the needle of having the coverage of the 2015 rule while simultaneously sidestepping some of the features that caused that rule to be partially stayed by federal courts.

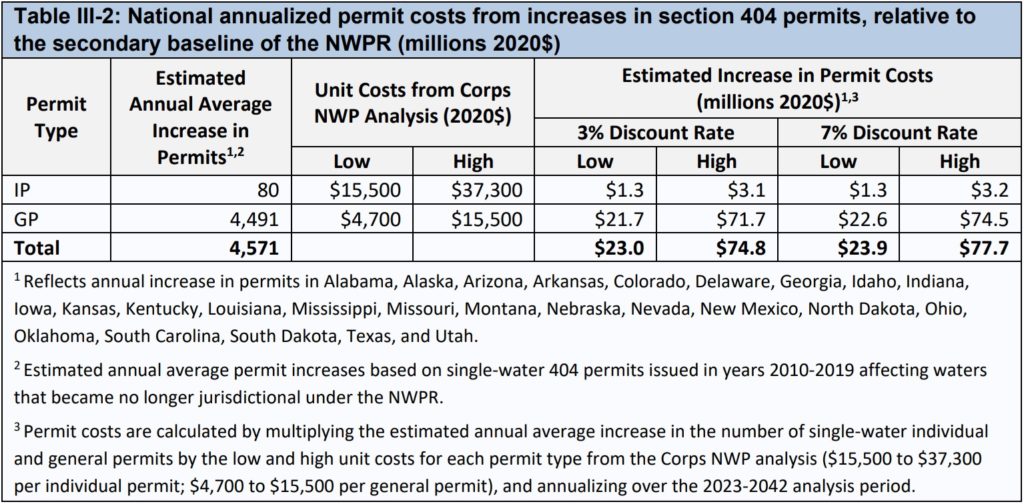

- Compared to the definition finalized by the Trump Administration, which this proposed rule would repeal, the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers estimate it could cost as much as $276 million more on an annual basis for permitting and mitigation for just one of the Clean Water Act’s most widely used permitting programs.

INTRODUCTION

The latest salvo in the ongoing struggle to durably define “waters of the United States” (WOTUS) arrived with the release of a notice of proposed rulemaking from the Environmental Protection Agency and the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Corps) (together, the agencies). The definition, punted to the agencies nearly 50 years ago by Congress, is critical as it underpins several federal regulatory programs.

The proposed rule makes the Biden Administration the third consecutive administration to attempt to create a definition that encompasses federal waters, excludes those that are not, and provides certainty to both the regulated and the regulators. This analysis explains the rule, compares it to recent predecessors, and assesses its implications.

WOTUS BACKGROUND

In amendments to the Clean Water Act (CWA) enacted in 1972, Congress delegated authority to the agencies to define the term WOTUS with the intent of protecting the navigable waters of the United States. As there are unnavigable waters that affect the quality of navigable waters, the delineation of what should be covered is uncertain. The term is important, however, because it determines where the federal government can prohibit or require permits for certain discharges or activities, such as land development. The inherent uncertainty has also led to several legal challenges. Three major decisions have been issued by the Supreme Court, with the latest in 2006.

That decision, known as Rapanos, sowed confusion on the regulations in place at the time, which were largely issued in 1986. In the case, Justice Kennedy sided with four conservative justices in the outcome, but not in their opinion (authored by Justice Scalia). As a result, the agencies issued a guidance document that aimed to reconcile the two separate opinions into the agencies’ enforcement.

Obama Administration WOTUS Rule

In 2015, the agencies issued a rule that sought to leverage Justice Kennedy’s opinion, which held that a feature should be considered a WOTUS if it has a “significant nexus” to navigable waters, into a broadening of the scope of federal waters. In addition to covering features that had a significant nexus to navigable waters — even those with only seasonal flows — it also classified certain waters as “jurisdictional by rule,” including some waters that may, in fact, not have a significant nexus to navigable waters. While the rule greatly expanded federal reach, it did allow for some greater certainty as to what waters would be covered (though many would still have been dealt with on a case-by-case basis). Subsequent legal action resulted in the rule being in effect in parts of the country and stayed in others. Before a final determination could be made by the Supreme Court, the Trump Administration stepped in.

Trump Administration WOTUS Rules

In his second month in office, President Trump issued an executive order directing the agencies to review the 2015 rule, and to revise it to ensure it reflected Justice Scalia’s opinion in the Rapanos case. That opinion centered on the premise that a WOTUS must be “relatively permanent” — or those that are relatively permanent, standing or continuously flowing and waters with a continuous surface connection to such waters — and likely excluding from coverage many of the ephemeral waters that would have been covered by Justice Kennedy’s significant nexus test.

The Trump Administration implemented in the order in two rules. The first repealed the Obama Administration’s rule and reverted to the 1986 rule. A second codified a new definition that limited coverage more closely to only those waters that are navigable, known as the Navigable Waters Protection Rule (NWPR). The rule would have had the effect of coverage that would be less than that of the 1986 rule and would also have provided more certainty. The NWPR, however, was vacated by a federal court earlier this year, primarily for not being protective enough.

BIDEN ADMINISTRATION ACTION

President Biden issued a sweeping executive order on his first day in office that directed agencies to review President Trump’s environmental rules. Following a review of the NWPR, the agencies issued the new proposed rule that can most easily be described as having the coverage of the 2015 rule with even less certainty over what waters are covered.

The rule would revert to the 1986 rule and, in the agencies’ explanation, modify it to incorporate both the Scalia and Kennedy opinions — but since essentially all waters covered by the Scalia definition would be covered by the Kennedy definition, this decision has the effect of broadening coverage of the rule closely to that of the 2015 rule.

Taken from the proposed rule’s preamble, the agencies would “interpret the term ‘waters of the United States’ to include: traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, and the territorial seas, and their adjacent wetlands; most impoundments of ‘waters of the United States’; tributaries to traditional navigable waters, interstate waters, the territorial seas, and impoundments that meet either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard; wetlands adjacent to impoundments and tributaries, that meet either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard; and ‘other waters’ that meet either the relatively permanent standard or the significant nexus standard.”

The proposal thus attempts to thread the needle of having all the coverage of the 2015 rule but without the categorical inclusions that were raised as problems in litigation but never sorted out by the Supreme Court. The agencies justify this approach by explaining that they aim to “promptly restore” longstanding protections, include amendments that reflect the best science, and avoid the questions that arose in the “complex litigation” of the 2015 rule.

The proposal also, by necessity, would formally repeal the NWPR. The agencies determined in their review of the rule that the NWPR was not protective enough to fulfill their obligations under the CWA — a determination bolstered by the rule’s vacation. As evidence, the agencies point to Corps data showing that under the NWPR 75 percent of nearly 10,000 determinations made were found to be non-jurisdictional. In contrast, in “similar 1-year calendar intervals” under the 1986 rule and post-Rapanos guidance, 55 to 72 percent of determinations were jurisdictional.

IMPLICATIONS OF THE PROPOSED RULE

The practical effect of the agencies’ proposal would be to greatly expand federal jurisdiction over the 1986 rule and to increase uncertainty beyond either the 2015 rule or the NWPR. Because the proposal eschews the 2015 rule’s categorical inclusions, the agencies will have to rely heavily on case-by-case determinations in any non-evident situation. This will have two obvious effects. The first is increased uncertainty for landowners, resulting in likely decreased land values due to the prospect that land tracts may be undevelopable at worst, or expensive to develop at best. The second is that more case-by-case determinations will increase the time and expense it takes for landowners to get a decision on whether their land is covered by the CWA, either by having the Corps make a determination or through hiring outside consultants, or both. These effects will have detrimental economic impacts.

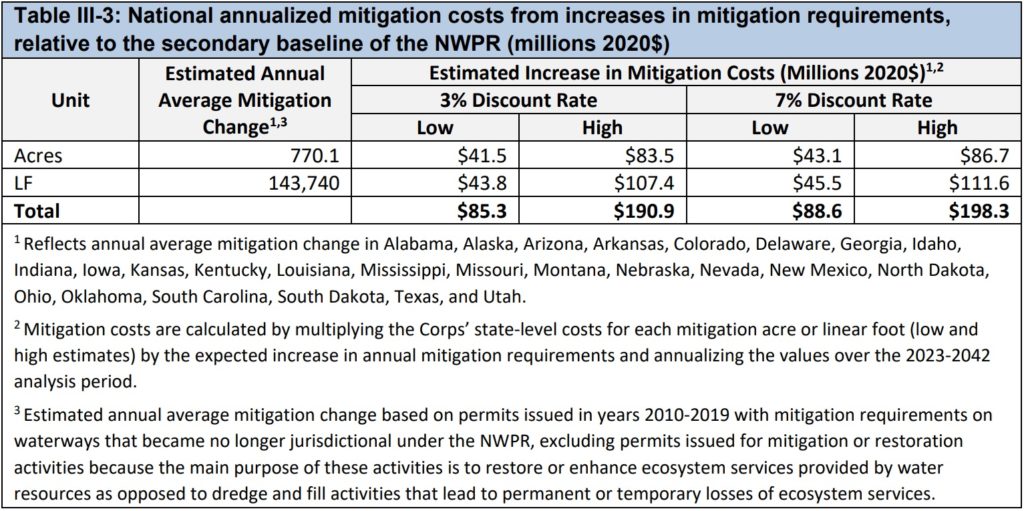

In terms of economic costs, the primary analysis conducted by the agencies concludes that the proposed rule will be “generally comparable to current practice” and there would be “no appreciable cost or benefit difference.” In their separate economic analysis, however, the agencies conduct a secondary analysis against a baseline of the NWPR for the Section 404 permitting program, one of the most popular CWA permitting programs. Compared to that, the rule will cost between $113 and $276 million for increased permit and mitigation costs on an annualized basis. These costs are broken down, respectively, in the following tables from the economic analysis.

For some context on mitigation costs, using the high estimate at a 7 percent discount rate would result in costs of $112,600 per mitigated acre. The same measure for linear feet would result in costs of $776 per mitigated linear foot.

There will also be legal implications from the proposed rule. Like its predecessor rules, it will surely be challenged once it is finalized. Whether it will be stayed like those rules, however, will be up to courts to decide. For proponents of regulatory certainty, a Supreme Court decision would be beneficial to avoid the mess that ensued following stays of the 2015 rule and the NWPR.

CONCLUSION

The Biden Administration’s proposed rule is the latest effort to offer a durable definition of WOTUS. The agencies’ proposal closely tracks the Obama Administration’s rule and repeals the Trump Administration’s version. Like those predecessor rules, its fate will ultimately be determined by federal courts.