Insight

March 1, 2021

The Consequences of Over-reliance on Executive Action

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

- Policymaking through executive action rather than legislation has become more prevalent in recent decades and while much of this shift is often attributed to partisan gridlock, a large share of the problem is due to Congress reducing staff levels in personal and committee offices and at its support agencies.

- The reliance on executive action creates uncertainty in the economy as well as attempted policy solutions that are both costly and inadequate to address major problems.

- In order to correct the executive/legislative imbalance, Congress must invest more in its own capacity and overcome the partisanship that prevents more efficient solutions on major issues than is available through regulations based on existing authorities.

INTRODUCTION

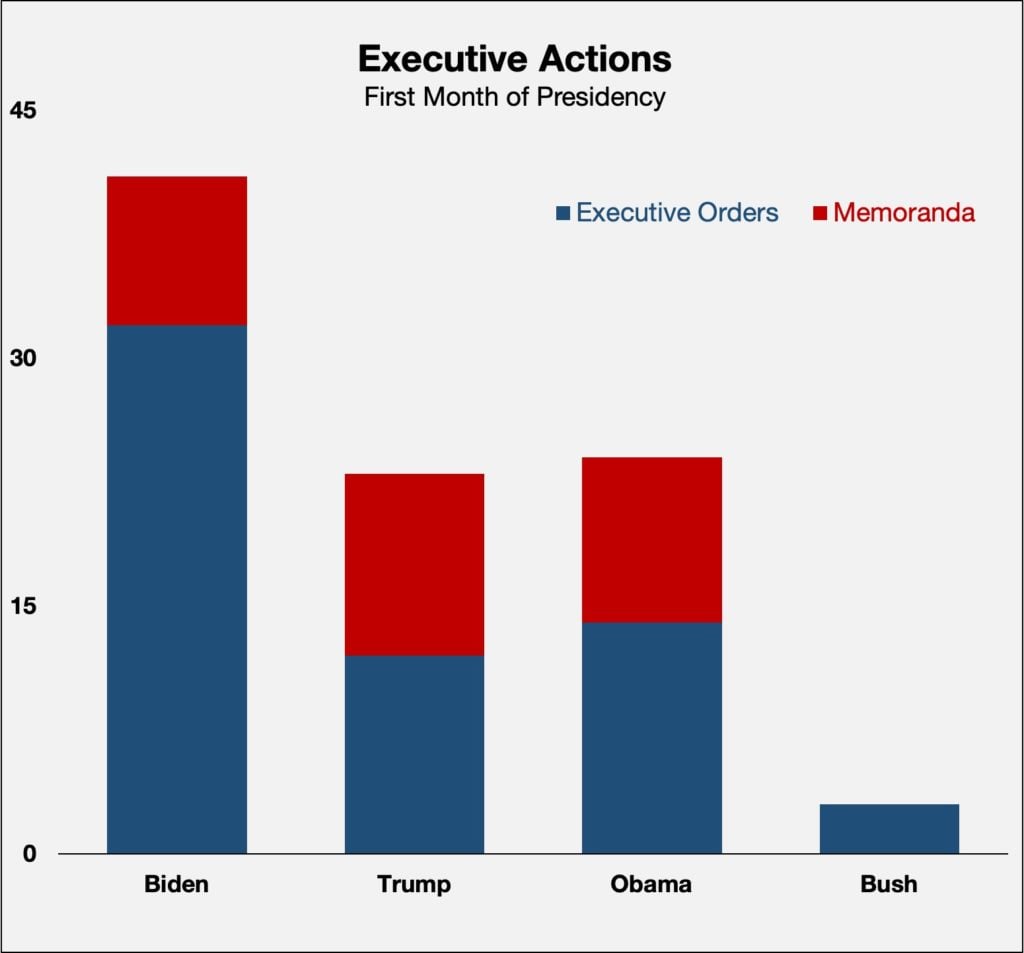

President Biden wasted little time in using executive action to implement his agenda. On his first afternoon in the White House, he signed nine executive orders and three presidential memoranda directing federal agencies to pursue certain actions or policies. His pace has only slightly slowed since then. By the end of his first month, he issued more than 40 such actions – far more than any of his recent predecessors. The actions suggest that using the federal regulatory machine will be central to his presidency.

While the number of executive actions in the first month of the Biden presidency has been noteworthy, the reliance on executive action to drive policy changes is hardly new. Recent presidents have increasingly relied on executive authority to enact significant policies when meeting congressional resistance. President Obama, for example, utilized the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to issue regulations on greenhouse gas emissions from power plants following a failure to pass cap-and-trade legislation through Congress. President Trump declared a federal emergency to fund his border wall when Congress refused to grant sufficient appropriations.

This analysis considers the causes of the increasing reliance of executive action to implement major policy, the consequences of this shift away from Congress, and suggests Congress needs to restore its role in establishing policy to limit expensive and inefficient policymaking.

THE RISE OF EXECUTIVE ACTION

The reliance on executive action has increased over the last two decades as Congress has become less productive, but the roots of the expansion of executive authority go back further. While partisan gridlock is well established and lends itself to increased executive action, partisanship’s effect is relative to the issues at hand. Another culprit bears much of the blame: congressional capacity.

Following the presidency of Franklin Roosevelt, which used executive action heavily, Congress recognized the need to give itself additional capacity to legislate and oversee executive action. From the late 1940s, legislative branch expenditures steadily rose for the next 50 years, with the majority of spending on increased staffing.[1] During that period, Congress largely took on the bulk of major new policymaking. It passed major regulatory legislation, including creating the EPA and the Occupational Safety and Health Administration, among many other agencies. It was also during this period that Congress passed notable deregulatory legislation, particularly in the transportation industries.

The measures passed during this period delegated a great deal of authority to the executive branch, requiring it to grow as well. While Congress largely continued to increase its capacity, it could not keep up. Then in the mid-1990s, congressional staffing levels began to decline. According to data from the Brookings Institution, House of Representatives committee staff from 1979-2015 levels reached a high of 2,321 in 1991, and a low of 1,014 in 2007. Similarly, Senate committee staff levels over the same period declined from 1,410 in 1979 to 951 in 2015. Staffing in personal offices and support agencies such as the Congressional Research Service also fell. According to a 2016 estimate, the legislative branch consisted of about 30,000 employees on a budget of $4.5 billion per year, while the executive branch had grown to 4.1 million employees and budget of $3.9 trillion.

The capacity reduction diminished Congress’s ability to legislate in a meaningful way. Research suggests that staffing matters to Congress’s legislative capacity, particular in creating linkages among different offices. As staffing has been reduced, those linkages, along with the experience, expertise, and peoplepower needed to craft good (and passable) legislation, have diminished. This reduced capacity also comes at a time when Congress has more on its plate.

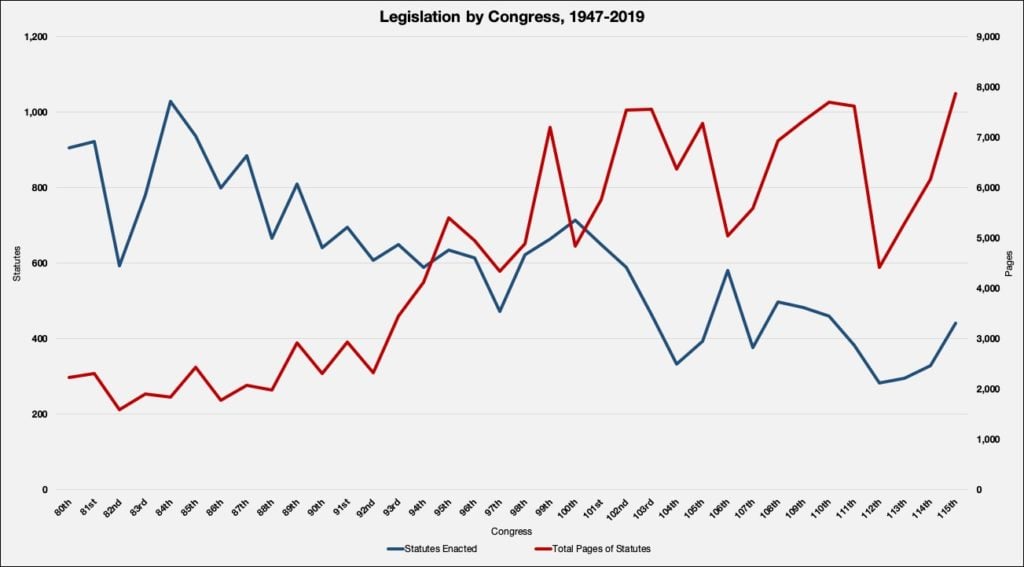

The chart below shows that since the late 1940s, the total number of laws passed is declining. At the same time, the total number of pages of passed legislation are increasing. The phenomenon is likely due to Congress increasingly relying on must-pass legislation such as appropriations and reauthorization bills as vehicles for other policy provisions. This phenomenon is also likely due to the fact that when Congress does pass substantial legislation, the bill is broad in scope and delegates substantial authority to the executive—the Affordable Care Act and the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act are good examples—which requires agencies to interpret the law and then enact numerous regulations implementing it. According to the Federal Register, those two bills have spawned 2,573 and 3,499 Federal Register entries, respectively.

Source: Vital Statistics on Congress, The Brookings Institution

In addition, as Congress does less, a power vacuum develops that the executive branch fills. Over time, this has become what Philip Wallach calls a “self-fulfilling prophecy,” whereby even Congress accedes to the fact that it has little say in the policy debate. Perhaps the best recent example of Congress ceding policy development was when Rep. Maxine Waters, chairwoman of the Committee on Financial Services, sent then President-Elect Biden a 45-page letter with recommendations of executive actions to counter Trump Administration policies. The fact that the head of a major congressional committee would be willing to abdicate a role in setting durable policies in the committee’s area of jurisdiction signifies Congress’s acknowledgement of its diminishing role in policymaking.

Sure enough, over the timeframe covered by the chart above, significant executive action has increased. According to data from the George Washington University Regulatory Studies Center, the overall trend of economically significant regulations has grown since the Reagan Administration. Recent presidents have increasingly used executive actions when unable to get priorities through Congress. President Obama, in addition to using the EPA to issue climate-related regulations following the failure to pass a cap-and-trade bill, created the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) policy following inaction on legislation. Similarly, in addition to pursuing a border wall through executive action, President Trump pursued regulatory actions on drug pricing when Congress could not come to a legislative solution and banned bump stocks through regulation.

Since a significant amount of policymaking now occurs via the executive branch, administrations increasingly spend their time reversing the executive actions or regulatory decisions of predecessors. President Obama attempted (but failed, notably) to close the detention facility at Guantanamo Bay via executive order. President Trump spent much of his term undoing (or attempting to undo) many Obama actions including DACA, the Clean Power Plan, and the overtime rule. The hallmark of the Biden Administration to this point has been to issue executive actions and memoranda aimed at reversing Trump Administration policies. His use of these actions over the first month of his presidency outpaces his recent predecessors, as shown in the chart below, and signals that executive action will be a primary means of implementing his agenda. If so, the reliance on executive action to set policy, followed by executive action in the opposite direction by subsequent administrations, will persist.

CONSEQUENCES

There are two main consequences of this back-and-forth – or as Wallach termed it in his recent analysis, the pendulum. The first, and most obvious, is economic. If major policies are reversed each time the presidency changes parties, then the private sector has a diminished ability to make confident decisions on long-term investments, hurting the prospects of future economic growth. When economic uncertainty is prevalent, consumers spend less, businesses limit production, investment, and employee compensation, and financial markets are more volatile.

The second consequence is a diminished ability for the United States to address major challenges, as regulations underpinned by old legislation are often expensive and less effective. This is because they were not designed with today’s problems in mind. For example, though the Clean Air Act gave the EPA Administrator the ability to designate new harmful pollutants, its implementation tools were not specifically designed for addressing carbon dioxide emissions. Research has shown that attempting to regulate these emissions is far more expensive than a legislative solution focused on carbon pricing, and not nearly as effective.

Over the next decade, the country will need to deal with significant issues including, but not limited to, addressing climate change and repairing and replacing major infrastructure. Both issues will require durable policies lasting beyond administrations.

A better approach to these tough issues would involve legislative solutions specifically tailored to addressing these challenges, rather than jerry-rigging expensive and inadequate regulations to conform to misaligned existing authorities.

In order for that to happen, Congress needs to reestablish itself as the solutions-developing branch of the federal government. Congress can take a first step toward reversing the imbalance by increasing its capacity. It should consider investing in staff to attain at least the levels of the early 1990s. This change would allow Congress to improve its expertise and increase its bandwidth to take a more proactive role in policymaking and agenda setting. Another step, albeit one that seems highly unlikely, is to reduce the partisanship and polarization that causes gridlock. There are, however, limited structural changes on this front that will significantly affect the situation; this is largely an issue of the broader political culture. While the political incentives are currently not conducive to bipartisan legislation, perhaps Congress will eventually recognize its marginalization and seek to correct it as major challenges pile up.

CONCLUSION

The first month of the Biden Administration signals that executive action will be a primary tool of implementing its agenda. While not new, this latest example furthers the trend of policymaking increasingly occurring through executive action. Using this means to craft policy makes policies less durable and ill-suited to address the challenges at hand. The results can have harmful economic effects. A major reason for the current reality is that Congress has marginalized itself through diminished capacity following a sustained period of delegating authority to the executive branch. Congress should correct these failures so that the United States can address major challenges in a way that is more economically efficient than through the existing regulatory structure.

[1] Bolton, Alexander, and Thrower, Sharece. “Legislative Capacity and Executive Unilateralism.” American Journal of Political Science, vol. 60, no. 3, 2016, pp. 649–663., www.jstor.org/stable/24877486. Accessed 22 Feb. 2021.