Insight

December 10, 2024

The Mechanics of Trump’s Tariffs

Executive Summary

- President-elect Donald Trump has proposed imposing tariffs on various countries, products, and companies for reasons ranging from protecting U.S. industries to targeting entities that engage in un-reciprocal, unfair, or undesirable trade practices.

- While tariff rates and their associated costs have garnered widespread attention, the underlying mechanisms for implementing Trump’s tariff plans are less clear, as each proposal is governed by different rules and requirements depending on the rationale behind each tariff.

- The most plausible and tested avenues for swift action would be using Section 301 to raise tariffs on Chinese goods or Section 232 to raise tariffs on goods with national security implications such as steel, the routes Trump took during his first term; using the International Emergency Economic Powers Act would be the fastest path toward a blanket tariff on all U.S. imports, though this approach would have more dubious legal standing and likely face hurdles that hinder unilateral enactment.

Introduction

President-elect Donald Trump has proposed imposing tariffs on various countries, products, and companies for reasons ranging from protecting U.S. industries to targeting entities that engage in un-reciprocal, unfair, or undesirable trade practices. Since 2018, tariffs have cost U.S. consumers roughly $300 billion or about $51 billion every year as both the Trump and Biden Administrations used them. While tariff rates and their associated costs have garnered widespread attention, the underlying mechanisms for implementing Trump’s tariff plans are less clear, as each proposal is governed by different rules and requirements depending on the rationale behind each tariff.

The most plausible and tested avenues for tariff action would be using Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974 to raise tariffs on Chinese goods or Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 to raise tariffs on goods with national security implications such as steel. Trump took these two routes during his first term and had successful implementation. The International Emergency Economic Powers Act (IEEPA) would be the fastest path toward a blanket tariff on all U.S. imports, although this approach would have more dubious legal standing and would likely face hurdles that hinder unilateral enactment due to it being untested for enacting tariffs. This insight will cover how the next Trump Administration might enact various tariff proposals as well as discuss each of the trade law processes relating to tariffs.

A Brief Background on Tariffs

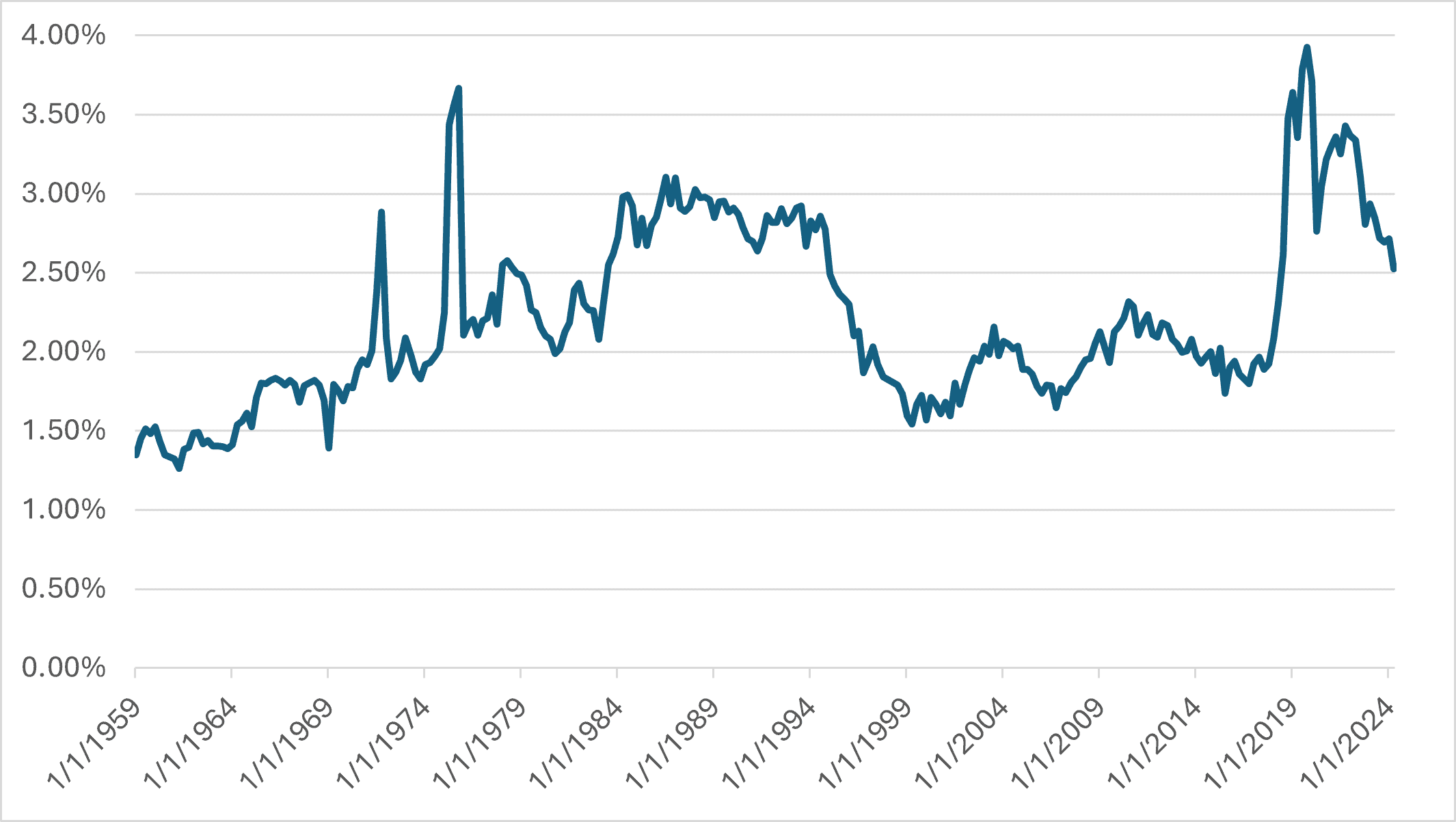

A tariff is a tax placed on imports entering a country for business or consumer purposes. Their costs can take the form of a percentage of the import price, a flat fee per unit, or a combination of the two. Tariffs are primarily used by a country to protect domestic industries from foreign competition by increasing the cost of foreign products for consumers, who inevitably end up paying the import tax or purchasing more domestic products. Tariffs are also used as a tool to defend up-and-coming industries, to ensure industries vital to national security are insulated from competition, to bargain with or retaliate against other countries’ trade barriers, and to raise government revenue. The United States received 2.5 percent of its revenue from tariffs in the second quarter of 2024, with this proportion peaking in the past 60 years at just under 4 percent in 2019. Customs duties have not been a significant source of revenue for at least a century.

Figure 1: Tariff Revenue as a Percentage of Total Federal Revenue

Source: St. Louis Fed

Historically, Congress has passed tariff legislation via the powers provided under Article 1, Section 8 of the Constitution, which directly grants the legislative branch the ability to impose taxes and duties as well as to regulate trade with foreign countries. More recently, the power of imposing, adjusting, and negotiating tariffs was delegated by Congress to the executive branch, and specifically to the president. This was done to provide the president more leverage when negotiating trade agreements with other countries, as well as to allow for a swift response to the rapidly evolving international environment. These changes to tariff authority have allowed the president to make unilateral decisions on trade policy, relegating Congress to a more observatory role unless it decides to reclaim its constitutional jurisdiction.

Examining Trump’s Tariff Proposals

President-elect Trump proposed tariffs throughout his campaign and has continued to issue threats of wide-sweeping tariffs following his election. If Trump’s first term is any indication, he sees tariffs as both a negotiating tactic and a blunt instrument to protect U.S. industries from perceived bad actors.

Across-the-board Tariff: Trump has floated the idea of imposing a 10-to-20 percent tariff on all imports into the United States. Trump has defended the proposal as being necessary to prevent foreign countries from taking advantage of the U.S. market, bring back manufacturing jobs that have been moved overseas, and to collect in revenue “a massive amount of money” for the federal government. Hypothetically, Trump could declare a national emergency invoking the International Emergency Economic Powers Act to implement a universal tariff as it grants the president wide authority over financial transactions in the name of national security. IEEPA remains an untested option but would be the quickest route for the Trump Administration to impose such a blanket tariff, provided it is not held up by lawsuits. Alternatively, Section 301 could be used on a country-by-country or product-by-product basis but would take months to implement – although success is far more likely. While Section 338 could be dusted off or Section 122 could be temporarily imposed, these mechanisms are much less likely to achieve the president-elect’s longer-term tariff goals.

Tariffs on China: Trump has suggested various tariffs on China ranging from 10 to 100 percent to address the flow of fentanyl into the country, national security concerns, unfair trade practices, and the loss of manufacturing jobs overseas. The most likely route for Trump’s China tariffs is through the use of the tried-and-true Section 301, which he used during his first term to place tariffs on hundreds of billions of Chinese goods that Biden maintained. Theoretically, a tariff could be immediately placed on China to address the fentanyl crisis, which would have to be declared a national emergency to use IEEPA.

Tariffs on Mexico: Trump has targeted Mexico with between 25 and 100 percent tariffs to address the flow of illegal immigration and 100 to 500 percent tariffs on all vehicles coming from the country to protect the domestic auto industry. The immigration crisis, which has eased in recent months, likely has more of a solid basis for the declaration of a national emergency as it could be coupled with concerns over fentanyl and drug-overdose deaths. As for auto tariffs, Section 301 or Section 232 could be used on cars, steel, or other components.

Tariffs on Companies: Trump has threatened to impose tariffs on companies that leave the United States and specifically proposed placing a 200-percent tariff on John Deere if it moves production abroad. Placing tariffs that target specific companies is unlikely to prove successful under any of the current tariff laws or procedures and would most certainly be challenged in court. Companies that move outside of the United States would more likely be punished via tariffs on the products they sell, which would undoubtedly have spillover effects on their broader industry.

Tariffs on BRICS: Trump has proposed a 100-percent tariff on the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) countries if they do not commit to using the U.S. dollar for international trade and finance. It is unclear whether the long-term threat of BRICS circumventing the dollar could justify the use of IEEPA and none of the other trade rules fit with this tariff’s intended purpose. Tariffs that target BRICS countries would have to be in response to other unfair trade practices rather than a direct response to an alternative BRICS currency.

Tariff Authority and Precedent

There are a number of trade law provisions on the books that provide the president power to impose tariffs. These rules have not, however, ended debate regarding how far, exactly, unilateral presidential authority extends and to what degree the president can levy tariffs on countries or products in the name of national security. Arguments on these issues have come into particular focus as President-elect Trump has proposed placing tariffs on all U.S. imports and even specific companies. Below are potential mechanisms that can be used to impose tariffs for varying reasons.

Figure 2: Overview of Presidential Authority Relating to Trade

| Mechanism | Use Case | Requirements | Precedent |

| IEEPA | Address a severe national security threat

|

Consult Congress before acting | Yes (not for tariffs) |

| Section 301 | Respond to unfair trade practices

|

Investigation by U.S. Trade Representative | Yes |

| Section 232 | Respond to imports with national security implications

|

Investigation by Department of Commerce | Yes |

| Section 201 | Provide temporary relief for a U.S. industry

|

Investigation by U.S. International Trade Commission | Yes |

| Section 338 | Allow tariffs on a country that discriminates against U.S. products

|

Investigation by U.S. International Trade Commission | No |

| Section 122 | Allow tariffs on imports to address a balance of payments deficit for 150 days

|

Seemingly unilateral decision | No |

Source: Tariff Act of 1930, Trade Act of 1974, Trade Act of 1962, Congressional Research Service

Section 301 of the Trade Act of 1974: This rule allows the president to place tariffs on countries that engage in unfair trade practices such as subsidization or intellectual property theft. It has been most commonly used to place tariffs on imports from China, as seen in 2018 with President Trump’s tariffs on over $200 billion worth of imports or more recently in 2024 with President Biden’s tariffs on $18 billion worth of Chinese electric vehicles, semiconductors, and other green-energy products.

Section 301 Process: Section 301 petitions are reviewed by the United States Trade Representative (USTR), which responds within 45 days to see whether an investigation is needed. If the petition is successful, USTR has a 30-day investigation period during which the government of the target country and other relevant advisers and parties are consulted. After consultations, a determination on whether the country has violated U.S. trade laws is finalized and the specific action is decided upon at the direction of the president. If a specific trade agreement is violated, final determination is required within 30 days, but if the unfair trade practices do not violate a trade agreement, then USTR must make a final determination within 365 days. Finally, once the proper corrective action is determined, USTR has 30 days to implement it. This entire process from petition to implementation can take as long as 135 to 470 days but could be “expedited” depending upon how determined the administration is to initiate an action.

As an example of this process, on August 18, 2017, USTR initiated an investigation of China, reported unfair trade practices on March 22, 2018, released a list of impacted products on April 3, 2018, revised the list on June 15, 2018, and imposed tariffs on July 6, 2018, and August 23, 2018. The process took roughly 322 days. In a second round of tariffs, it took just 98 days.

Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962: This rule is used to raise tariffs or restrict imports of goods in the name of national security. It has been broadly used on imports of steel and aluminum from nearly every country to ensure domestic production is not jeopardized. Exemptions are currently in place for Mexico, Canada, Argentina, South Korea, and Brazil, with the European Union, Japan, and the United Kingdom only facing tariffs after a certain import threshold. President Trump invoked Section 232 in 2018 to place 25-percent tariffs on steel and 10-percent tariffs on aluminum.

Section 232 Process: Any relevant party, such as an agency or department, can submit an investigation request to the Department of Commerce (which can also initiate its own investigation), which must report its findings within 270 days. During the investigation, Commerce consults with the secretary of Defense, and takes into account national security considerations such as domestic production, capacity needs, defense supply demands, and growth requirements. Other considerations include the impact of foreign competition on domestic industry, the effect displacement of a certain good could have on the U.S. economy, and any other factor that could weaken the United States. If the investigation report to the president recommends action, the president has 90 days to determine what measures to take (if any). Once a decision is made, the president has up to 15 days to implement the action and 30 days to inform Congress. This entire process from investigation request to presidential action can take up to 375 days but depends on the expediency of the administration.

As an example of this process, on April 19, 2017, Commerce initiated an investigation into steel, and another investigation into aluminum on April 26. In January 2018, Commerce gave recommendations to President Trump and, on March 23, the United States imposed tariffs on both goods. The process took roughly 338 days.

Section 201 of the Trade Act of 1974: This rule allows the president to “safeguard” a U.S. industry or product for up to four years (maximum of 8 years if extended) through the use of tariffs or other import restrictions. The rule is designed to temporarily assist domestic industries so they can adjust to greater foreign competition. President Trump previously used Section 201 for washing machines and solar cells, with President Biden extending the solar cell safeguards in 2022 for an additional four years.

Section 201 Process: A Section 201 petition can be initiated by U.S. workers or firms and is then investigated by the U.S. International Trade Commission (ITC), which may also initiate a on its own.to the ITC must include a plan for that industry to adjust to foreign import competition within the “safeguard” period. During the investigation, hearings are held, and public comments are taken to examine whether the industry in question is seriously threatened. If the situation is “extraordinarily complicated,” (which is open to interpretation) 30 days can be added to consider the injuries to the U.S. industry, but findings must be reported within 180 days of the petition. Injuries include the idling of production, the inability of domestic firms to produce for reasonable profit, and high unemployment. Once a recommendation is selected, the president has 60 days to decide on an action, which is then reported to Congress. If the presidential action differs from ITC recommendations or the president takes no action, Congress may pass a joint resolution within 90 days, which may then become the remedy. This entire process can take roughly 255 days; however, if Congress acts, the finalized action could take up to 345 days.

As an example of this process, manufacturers initiated a petition for solar cells on May 17, 2017, and for washing machines on June 6, 2017. Presidential action on both products came on January 23, 2018. These processes took 251 days and 231 days, respectively.

Section 338 of the Tariff Act of 1930: This rule allows the president to impose tariffs up to 50 percent on any country that discriminates against goods from the United States. Discriminatory actions could include foreign tariffs, import restrictions, or regulatory hurdles that disadvantage U.S. products. If the targeted country continues to disadvantage U.S. exports, the president has the ability to fully block trade from that country as a retaliatory measure or potentially escalate Section 338 to apply to other countries that benefit from the discrimination against U.S. goods. This was last used as a bargaining tool in the 1930s but has never been officially used by the executive branch since.

Section 338 Process: Section 338 does not have a formalized or tested process for implementation, so it is unclear what the timeline could be from an investigation by the ITC to implementation by the president. An obstacle to its use that would hypothetically delay immediate action would be legal challenges to presidential authority.

Section 122 of the Trade Act of 1974: This rule allows the president to impose tariffs of up to 15 percent on imports to address a balance of payments deficit or prevent significant dollar depreciation. These tariffs would only last for a period of up to 150 days unless extended by Congress. Tariffs or import restrictions under this rule are also intended to be non-discriminatory and applied consistently but may be targeted toward specific countries. Section 122 has not been used in this manner and was added only after President Nixon imposed tariffs to address trade deficits using the predecessor to the International Emergency Economic Powers Act.

Section 122 Process: Section 122 does not have a formalized process for implementation, so it is unclear what the timeline could be from the investigation period to implementation.

International Emergency Economic Powers Act of 1977: This rule allows the president to impose controls on transactions or freeze foreign assets to address a threat to national security. The intellectual decedent of the Trading with the Enemy Act of 1917 (TWEA), IEEPA has been used to issue embargoes and sanctions on countries in times of crisis or in response to perceived dangers to the United States. President Trump proposed using this authority in 2019 to threaten Mexico in response to illegal immigration but never used the authority to impose tariffs of any kind. President Nixon used TWEA to impose tariffs in response to a declared national emergency, however, suggesting that IEEPA could be used in the same way.

IEEPA Process: To use IEEPA, the president must declare a national emergency utilizing the National Emergencies Act or cite IEEPA in an executive order. In the past four years, there have been 12 national emergency declarations and 34 executive orders in which the IEEPA was cited. IEEPA can be cited directly by the president or Congress could direct the president to act using its authorities. National emergencies that use IEEPA, surprisingly, have never been terminated via Congress, despite the fact they lasted for an average of nine years since 1977 and 15 years in the 2000s. This process, unlike the others, does not require an investigation period, which radically reduces the time it would take to implement actions, but it is unknown whether tariffs invoked under IEEPA would face a drawn-out legal battle.