Insight

May 1, 2019

There is no National Security Benefit to Rejecting a Jones Act Waiver for Natural Gas

Summary

- The Trump Administration is considering waiving the requirements of the Jones Act for the domestic natural gas trade.

- The Jones Act requires that all goods traded between domestic ports be shipped on American-built, American-flagged, and American-crewed vessels, and it is forcing Americans in New England and Puerto Rico to purchase more expensive foreign natural gas.

- The national security rationale for the Jones Act is diminished, as the presence of the policy is forcing purchases from foreign suppliers and harming U.S. energy security.

- The remaining rationale for the Jones Act is for the government to support domestic shipping and shipbuilding, but these industries are in marked decline, suggesting that it may be time to reexamine the policy’s effectiveness.

Introduction

The Jones Act requires that all goods traded between domestic ports be shipped on American-built, American-flagged, and American-crewed vessels. This requirement has forced parts of the United States without sufficient pipelines to import natural gas from other countries because there are no American-built liquified natural gas (LNG) tankers to bring the cheaper domestic supply. In response, the Trump Administration is reportedly considering offering a waiver from the requirements of the Jones Act for LNG intranational trade. Put simply, Americans in New England or Puerto Rico would be allowed to purchase LNG from American suppliers without having to use an American LNG tanker to ship it.

The benefits of this waiver are fairly obvious—American customers would be able to buy cheaper domestic natural gas, while American natural gas suppliers would have more customers. Yet defenders of the Jones Act contend that a waiver would undermine its national security objectives of sustaining a domestic shipbuilding industry. Over the years, however, the apparent national security benefits of the Jones Act have declined, while the economic burdens of it have increased. In the case of natural gas, the Jones Act is actually harming U.S. national security, as it is creating an unnecessary dependency on foreign energy suppliers.

The National Security Rationale of the Jones Act

The logic of the Jones Act, a section of the Merchant Marine Act of 1920, was not dictated by any economic rationale, but rather foreign policy considerations of the period. A German U-boat sunk the British ocean liner Lusitania in 1915, dragging the United States into World War I. The event highlighted the precarious nature of the United States’ ability to sustain supply chains and project power to distant threats. The United States saw, correctly, that its naval power would affect any subsequent war with a European power—and indeed, in World War II Hitler tried to disrupt shipments from the United States to the Europe. Hitler’s efforts were thwarted in no small part due to the massive shipbuilding capacity of the United States. America produced ships faster than German U-boats could sink them, and the Jones Act may have had some role in ensuring a nascent shipbuilding industry that was available to ramp up (other policies, like the Emergency Shipbuilding Program, had a more prominent role). The national security environment is much different today, however, and the argument that the Jones Act is a significant contributor to present-day national security does not hold up to scrutiny.

The national security defense of the law fails on multiple fronts. First, the underlying strategy is dated. The United States is now the leader in all forms of naval warfare: It has the most advanced submarines, the most aircraft carriers, and arguably the best anti-submarine warfare capabilities. In contrast to 1920, when there was little defense against raids on naval supply chains from submarines, and the strategem of being able to build more ships than the enemy can intercept is less relevant in an era of long-range anti-ship missiles.

Second, a common defense of the Jones Act is that it is necessary to ensure sufficient sealift capacity of U.S. flagged vessels. By protecting a market that only American shipbuilders can fulfill, it ensures that if shipbuilding capabilities need to be ramped up the expertise and industry already exists. But in reality, when sealift capacity has been insufficient the Jones Act has not provided the backstop that its creators intended. For one thing, the number of Jones Act eligible vessels has been declining. There are presently only 99 Jones Act eligible vessels, while in 2000 there were 193. For another, the United States primarily relies on the National Defense Reserve Fleet (NDRF) to reactivate old ships to procure sealift capacity, rather than build new ones which may not be ready quickly enough.

Third, the requirements of the Jones Act create a perverse incentive for Americans to purchase foreign products to avoid the higher costs. The average residential price of natural gas in New England is 53 percent higher than the national average (as of January 2019). The unavailability of pipelines would normally signal American sellers to ship natural gas as LNG to New England, but the Jones Act outright prevents this and forces New Englanders to purchase LNG from foreign suppliers. This includes Trinidad and Tobago, which is now getting natural gas from Venezuela, and France, which gets a substantial amount of its natural gas from Russia. If defendants of the Jones Act are concerned about foreign powers’ influence in U.S. markets, the Jones Act actually worsens the situation.

Regardless of the merit of the points against the Jones Act, some defendants of the policy are undeterred, believing that the core aspirational value of the policy—the preservation of U.S. shipbuilding capabilities—are eroded by any waiver, or any weakening of the law’s authority. Even when no U.S. jobs are at risk, and the economy and national security are harmed by refusing to waive the Jones Act, it is defended on principle. Unfortunately, the idea that the Jones Act has been a low-cost solution to preserving the U.S. shipbuilding industry is fundamentally at odds with the data.

The Economic Costs of the Jones Act and the State of the Shipping Industry

For regular container shipping (in contrast to LNG shipping), Jones Act vessels do operate regularly, but the requirement for many to use Jones Act vessels instead of a foreign competitor comes at a premium. It is difficult to know exactly how much the Jones Act increases the prices of products in affected markets, as many variables influence price. It is perhaps for this reason that many are under the impression that its costs are small, or otherwise worth bearing for national security purposes. A study commissioned by a Jones Act advocacy group claimed, using food price comparisons, that the costs of the Jones Act to Puerto Rico are small. Yet several reputable studies directly contradict claims that the Jones Act imposes little cost.

In 2013, the Government Accountability Office (GAO) analyzed the impact of the Jones Act on intranational commerce between Puerto Rico and the U.S. mainland. The report found that only four carriers were eligible to ship goods to Puerto Rico from the mainland, and this limitation generally led to higher prices for U.S.-sourced products than for foreign imports. Not surprisingly, the narrow shipping market was also ripe for manipulation, and three of the four carriers paid $46 million in criminal fines for acting as a cartel to manipulate freight rates from 2002 to 2008.

Another GAO study, performed in 1988, estimated the impact of the Jones Act on shipping costs in Alaska. The study found that the Jones Act increased the costs of intranational trade by $163 million annually. And the costs have likely risen significantly in the three decades since then.

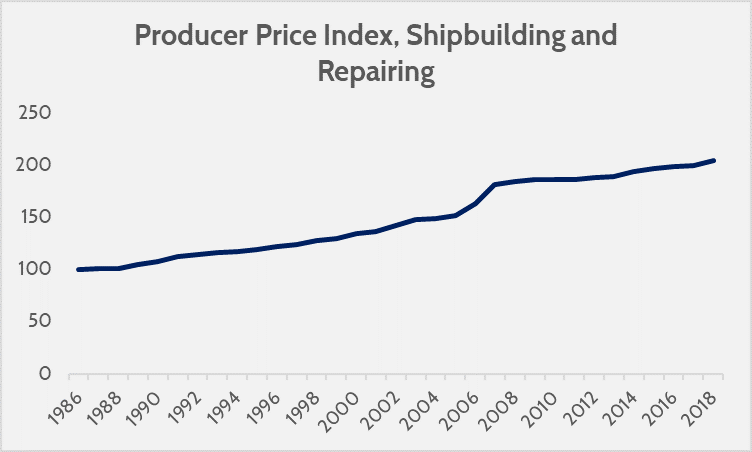

Since 1986, the Producer Price Index for the shipbuilding industry, a measure of the increased costs of producing goods, has increased by 104.6 percent.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

That increase would be inconsequential if shipbuilding costs had risen proportionally around the world, but that is not the case. The Center for Naval Analyses notes that U.S. shipbuilding is suffering because there are too few orders for large vessels, and the reason there are so few orders is because U.S. ships are more expensive than their foreign counterparts. That report is from 2002, and the situation has likely only further eroded in the nearly two decades since, as shipbuilding employment has declined.

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis

Not only are these ships more expensive to build; they are more expensive to operate. A GAO report from last year noted that, 10 years ago, operating a U.S.-flagged vessel cost $4.8 million more per year on average than operating a foreign-flagged vessel—and those costs have risen to $6.2 to $6.5 million today. As there are 99 shipping vessels that satisfy the Jones Act criteria, the total annual cost of using Jones Act vessels instead of equivalent foreign ships is an average of $614 to $644 million per year. The higher cost of operating U.S. flagged vessels has led to another program, the Maritime Security Program (MSP) which pays U.S. flagged vessels participating in international trade an annual stipend of $5 million, or $300 million for the whole program each year (60 participating vessels).

In short, the express purpose of the Jones Act is to ensure that the United States maintains a tradition of having a healthy shipbuilding industry, but the data shows that even with the protection of the government, and taxpayer subsidies for the U.S. flagged vessels in the MSP, the shipbuilding industry is in decline. The Jones Act has not been successful at preserving this industry, and more of the same does not benefit either the economy or national security.

Conclusion

The only conceivable justification for the Trump Administration to reject a Jones Act waiver in this case is that the Act has been so critical to maintaining the U.S. shipbuilding industry that any encroachment on its authority would weaken the protected industry. The data indicate, however, that the U.S. shipbuilding industry is in decline despite its Jones Act protections. If policymakers are sufficiently concerned with the threats that a declining shipbuilding industry could present, then alternative policies to the Jones Act should be examined, as relying on it is clearly ineffectual. If sealift capacity needs to be expanded, policymakers should focus on the NDRF or the MSP. If being able to procure military vessels is important, then simply procure the vessels rather than using market interventions and dispersed costs to circuitously buoy demand.

In the meantime, a waiver for LNG shipments under the Jones Act would go a long way to benefiting both America’s economy and its national security. It would end the artificial preference for foreign natural gas purchases and reduce energy costs for Americans (including beleaguered Puerto Ricans), and the policy would have no tradeoffs because there is no domestic LNG tanker industry to be protected.