Research

February 20, 2018

Examining the Effects of Recent and Proposed Reforms to Medicare Part D

Updated and corrected August 1, 2018

Executive Summary

- Nearly three out of every 10 Medicare Part D enrollees face annual drug expenditures high enough to be considered a high-cost enrollee. The Bipartisan Budget Agreement (BBA) of 2018 made changes to the Medicare Part D prescription drug program that are likely to save these high-cost enrollees $350 annually in out-of-pocket costs.

- However, these changes also have the potential to weaken the very structure of the Part D program that has led to its success by reducing insurers’ liability by an estimated $1 billion in 2019 alone and thus their incentive to control costs.

- President Trump’s FY2019 budget also includes several changes to the Part D benefit design. Assuming the BBA were never passed, these changes would increase insurer liability by an estimated $4.7 billion in 2019. This increase should eliminate a perverse incentive that led insurers to prefer coverage of high-cost, high-rebate drugs at the expense of taxpayers and patients with the highest prescription drug costs.

- If the president’s changes are implemented in addition to the recent changes made by the BBA, however, insurer liability would be reduced by an additional $4.5 billion, resulting in net total savings to insurers of more than $5.6 billion in 2019, further exacerbating the problem created by the BBA. Thus, while some patients will likely see a reduction in their out-of-pocket costs in the short term, undermining the competitive structures of the program threatens to drive up costs for everyone in the long term.

Introduction

The Medicare Part D prescription drug program has been highly successful, and that success is attributable to the incentives that drive competition among the insurers offering Part D plans. Those incentives result from and are directly proportional to the insurers’ responsibility for the costs incurred and the possibility of financial reward for keeping costs low. The recently passed Bipartisan Budget Act (BBA) of 2018 and the president’s recently released FY2019 budget include actual and proposed changes to the Part D program which will impact the strength of those incentives. This paper analyzes the potential effects of these policy changes and proposals. However, it is important to note that this analysis is based on historical expenditure data and does not account for the myriad behavioral changes which may occur as a result of such policies.

Background: High-Cost Beneficiaries

For all the attention paid to high drug costs over the past few years, the number of Medicare beneficiaries incurring particularly high out-of-pocket (OOP) costs is relatively low. In 2015, 3.6 million Medicare Part D beneficiaries incurred prescription drug costs high enough to be considered a high-cost enrollee by reaching the catastrophic phase of their prescription drug insurance coverage.[1] The share of beneficiaries considered to be high-cost has been growing at an average annual rate of 9 percent since 2010.[2] These individuals take an average of 9.5 prescriptions per month with an average negotiated price per prescription of $193, for an estimated total average annual drug cost of nearly $22,000 in 2015.[3]

Relatively few of these Part D participants are themselves spending a large sum of money. Of these high cost enrollees, 2.6 million are eligible for the low-income subsidy (LIS). By law, LIS beneficiaries pay no more than $8.35 for each brand-name drug they take and even less for generics.[4], [5] These LIS beneficiaries paid an average of $113 in total OOP expenses in 2015.[6] Thus, the beneficiaries likely to be impacted by the reforms discussed in this analysis are the remaining one million non-LIS high-cost enrollees. These remaining individuals accounted for just 2.4 percent of all Part D enrollees but 20 percent of all Part D OOP costs.[7]

Methodology

The estimates in this analysis are based on 2015 average per capita expenditures (the most recent publicly available) for LIS and non-LIS high-cost enrollees.[8] Expenditure projections beyond 2015 assume a steady annual growth rate in per capita expenditures of 10.4 percent, equal to the annual growth rate in expenditures per high-cost enrollee from 2010 to 2015.[9] Total expenditures in each phase of coverage were calculated based on the known deductible, initial coverage limit, and catastrophic coverage threshold, and the coinsurance rates for each stakeholder in each phase of coverage based on the standard Part D benefit design. Expenditures in the coverage gap reflect the ratio of brand-name to generic expenditures included in the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services Part D Call Letter each year.[10] The 2019 Call Letter was also used to determine the expenditure threshold for each phase of coverage in 2019. Enrollment levels of both LIS and non-LIS beneficiaries are as projected in the most recent Medicare Trustees Report, and it was assumed that the same percentage of enrollees reaching the coverage gap and catastrophic coverage in 2015 would do so in the baseline (pre-BBA) scenario.[11]

Estimates of aggregate insurer liability in the coverage gap assume the average expense per enrollee who reaches the coverage gap but does not reach catastrophic coverage would be half the expense of a beneficiary who does reach catastrophic coverage. Estimates of aggregate insurer liability in the catastrophic coverage phase under the BBA assume the share of high-cost enrollees increases by 10 percent; this increase is believed to be a high bound and is intentionally used to show that even with that significant of an increase in the number of beneficiaries reaching catastrophic coverage, insurer liability would still decline relative to the pre-BBA baseline. In each of the scenarios modeling the changes included in the president’s budget, it was assumed that only 20 percent of those individuals expected to reach catastrophic coverage in the pre-BBA baseline would do so as a result of two specific changes: the amount of spending that would have to occur before beneficiaries reach the catastrophic coverage threshold more than doubling, and manufacturer rebates no longer accelerating beneficiaries through the coverage gap.

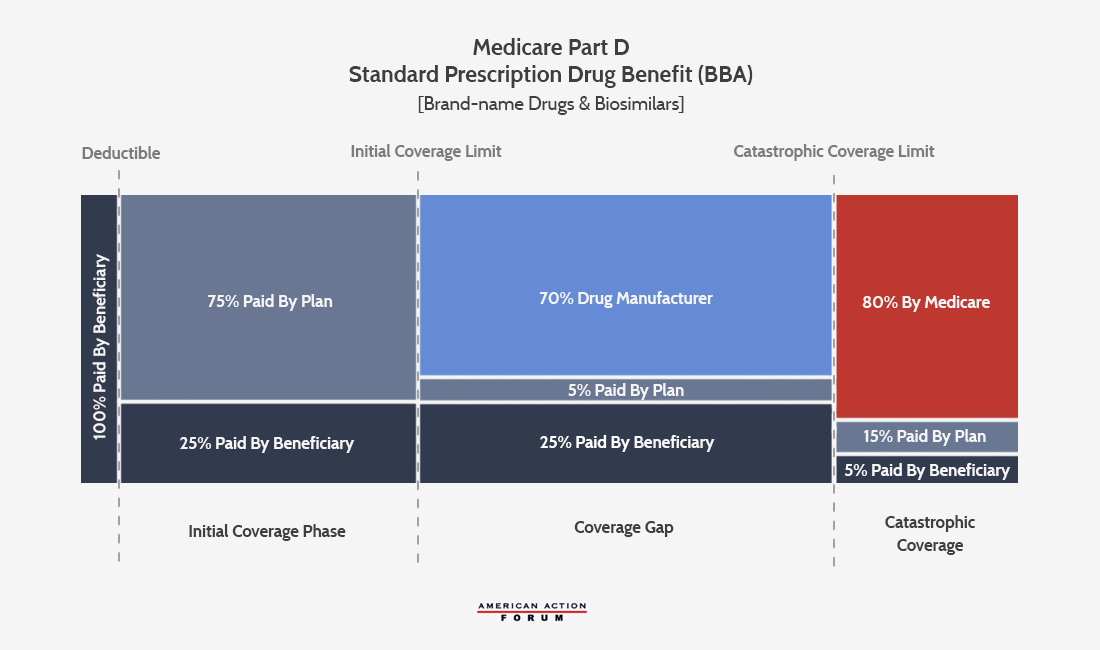

Changes in BBA of 2018

On February 9, 2018, President Trump signed into law the Balanced Budget Act of 2018, which included a significant change to the structure of the Medicare Part D program (as explained here). Drug manufacturers will now be required to increase the size of the required rebate they pay when a beneficiary is in the “coverage gap” phase of their Part D plan, from 50 percent of the negotiated price of the drug (as was required under the Affordable Care Act, or ACA) to 70 percent. This 20 percent hike is expected to increase manufacturer rebates by approximately $400 for each high-cost enrollee in 2019. Assuming 26 percent of beneficiaries continue to reach the coverage gap, total costs for drug manufacturers could increase between $3.5 billion and $7 billion.

This rebate hike also has important implications for Part D plan sponsors. The increased drug manufacturer rebates will not reduce the coinsurance rate patients pay for their drugs. (The BBA does accelerate when beneficiaries pay only 25 percent of the cost of their drugs; the ACA had patients in the coverage gap paying 30 percent in 2019 and 25 percent in 2020.) Rather, the increased rebate reduces what the insurer would have paid toward a patient’s costs in the coverage gap.

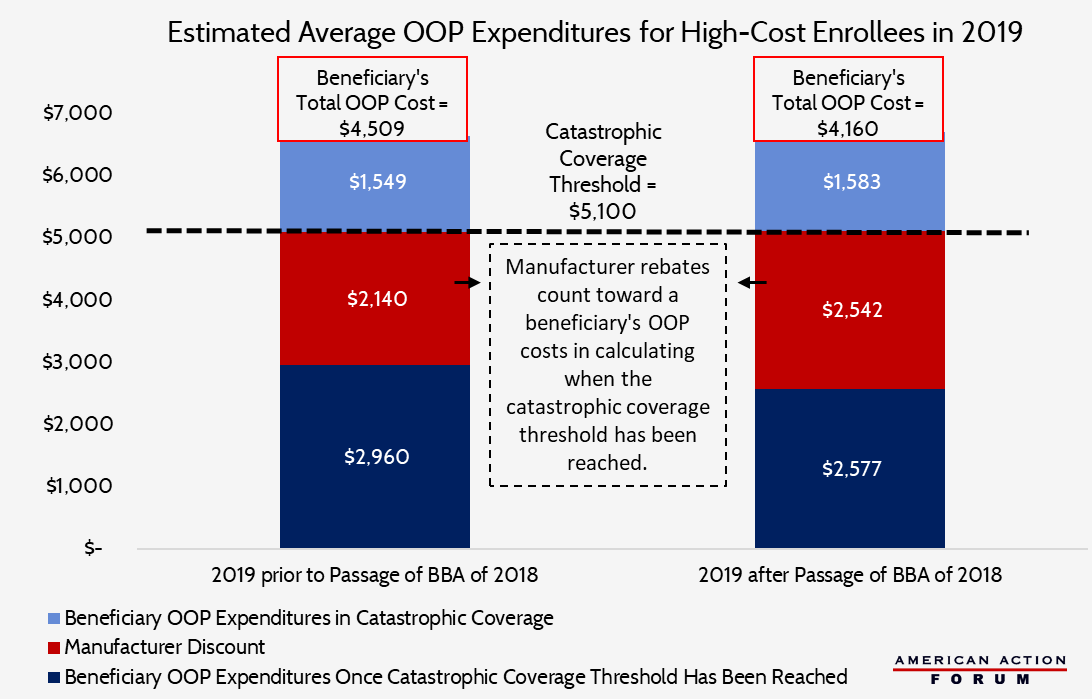

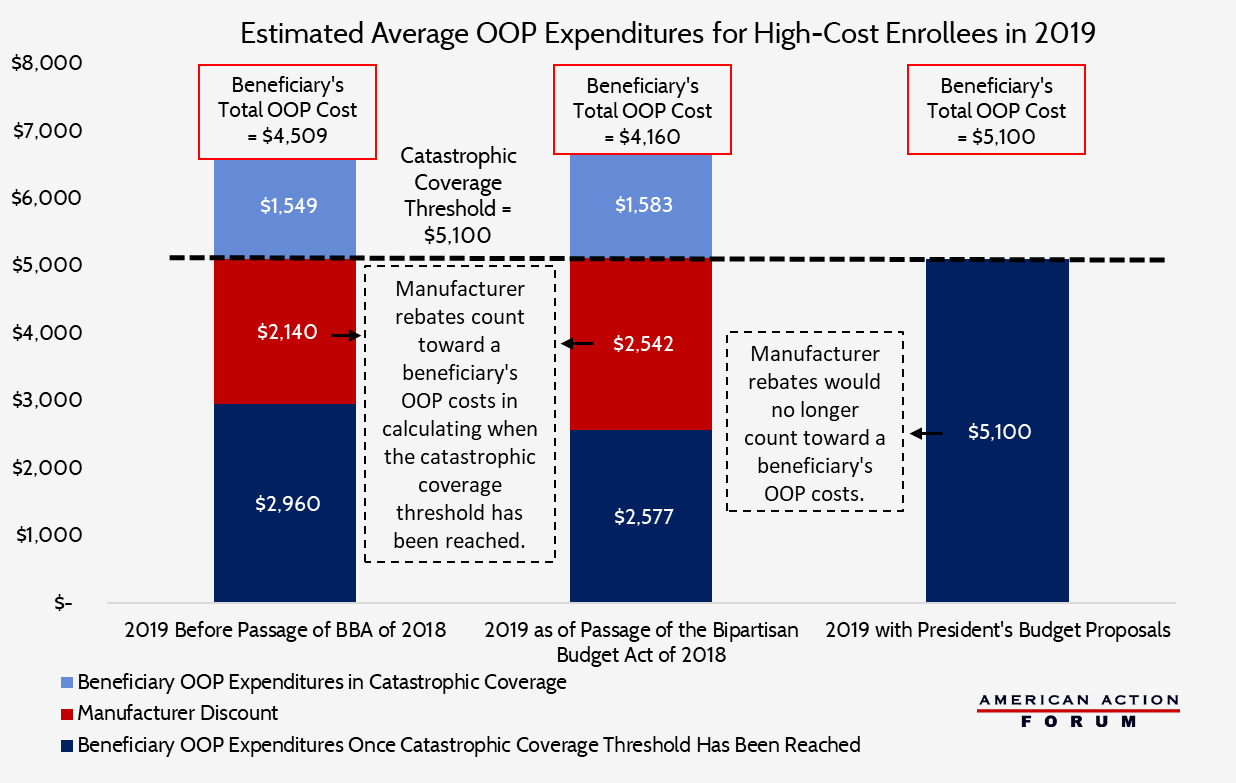

These changes have two effects. First, beneficiaries will reach the catastrophic coverage phase more quickly, at which point their OOP costs drop dramatically. Under current law, manufacturer rebates (but not insurer expenditures) count toward beneficiaries’ calculated OOP costs when determining when the beneficiary reaches the catastrophic coverage threshold. The BBA’s change will reduce the amount of total drug spending required to move a patient into the catastrophic phase of coverage by an estimated $700, and will reduce total OOP expenditures for high-cost enrollees by $350, on average, as shown in the chart below. Roughly two-thirds of the savings would result from the increased manufacturer discounts speeding the beneficiary through the coverage gap, while the remainder would be attributable to the accelerated reduction in the beneficiary’s coinsurance rate in the coverage gap.

Second, by reducing the insurers’ liability in the coverage gap down to only 5 percent, insurers will save nearly $700 for each high-cost enrollee and an estimated $2.4 billion for all beneficiaries in the coverage gap. Assuming a 10 percent increase in the share of beneficiaries entering the catastrophic phase of coverage due to the increased manufacturer rebates, insurer expenditures in the catastrophic phase (where they are responsible for 15 percent of costs) will rise by an estimated $1.35 billion. On net, overall insurer liability beyond the initial coverage limit is expected to decline by just over $1 billion, or 4 percent, in 2019 as a result of the BBA’s changes. This liability reduction could reduce the incentive for insurers to control drug costs beyond the initial coverage limit—a move that would undermine the market-oriented structures that have made the Part D program so successful.

Proposals in the President’s Budget

The president’s FY2019 budget includes many proposals aimed at reducing drug costs, several of which would make additional changes to the Part D program, including reforms recommended by the Medicare Payment Advisory Commission (MedPAC) in June 2016. Specifically, the budget proposes: 1) capping beneficiaries’ OOP costs at the catastrophic coverage threshold (currently, there is no cap on OOP expenses); 2) excluding manufacturer rebates from counting toward a beneficiary’s calculated OOP costs; and 3) changing the share of liability in the catastrophic coverage phase such that the government (which currently covers 80 percent of catastrophic costs) would only pay 20 percent and insurers (which currently pay 15 percent of those costs) would now pay 80 percent. The 5 percent share currently paid by beneficiaries would be eliminated by the new OOP cap.

The Budget’s Scope of Impact

In considering the impact of these proposed changes, keep in mind that only 28 percent of beneficiaries historically have incurred costs high enough to enter the coverage gap and thus be impacted by the changes being discussed.[12] Further, only 10 percent typically reach the catastrophic coverage phase. Total annual spending for that 10 percent of beneficiaries (including costs covered by the beneficiary, insurer, drug manufacturer, and the government) averaged more than $27,000 in 2015; the beneficiaries themselves paid average OOP expenditures of approximately $4,000.[13] The OOP catastrophic coverage threshold that year was $4,700, or $1,000 above what the average non-LIS high-cost enrollee actually paid OOP.[14] This difference is equal to the average manufacturer rebate paid on behalf of these individuals in the coverage gap. Thus, assuming that 2015 numbers hold and manufacturer discounts are not counted toward OOP costs as the president is proposing, an average high-cost enrollee will not benefit from a cap on OOP expenses imposed at the catastrophic coverage threshold because their costs are not high enough. Some beneficiaries will see a cost increase, however—negating much of the benefit gained from the BBA’s changes to Part D, as shown in the chart below—but still with costs below the OOP cap.

A small subset of non-LIS, high-cost enrollees do, however, incur OOP costs well above the average for this group of individuals. In 2015, more than 100,200 individuals had OOP costs exceeding $5,200, and 10,000 paid nearly $9,500 in OOP costs.[15] All of these individuals would have benefitted from the cap on OOP costs if it had been imposed that year, but they represent less than 1 percent of all Part D enrollees. That said, a cap does give every beneficiary the peace of mind in knowing that there is a limit on their expenses should anything change.

How the Budget Changes Insurers’ Financial Incentives

The proposed change in insurers’ liability during the catastrophic phase of coverage should dramatically reshape their incentives, though the impact of this change will be noticeably different if applied now, given the changes of the BBA, than they would have been absent the BBA’s changes. The intent of the shift in financial incentives is to encourage plan sponsors to find new ways to help control (and possibly reduce) overall program costs, which could change the program’s current financial trajectory. Given Medicare’s dire fiscal outlook, such a result would be welcome.

The ACA, through its provisions to close the coverage gap, created a situation that lessened insurers’ financial incentives to control costs for beneficiaries who were expected to reach the catastrophic coverage phase. Under the ACA, insurers would be responsible for a smaller share of a beneficiary’s costs in the catastrophic period than in the coverage gap. Additionally, as previously discussed, the ACA required that manufacturer discounts in the coverage gap be applied toward a patient’s calculated OOP costs. The combination of these two policies led insurers to prefer to cover high-cost/high-rebate drugs, as larger rebates accelerated patients’ move into the catastrophic period. The proposals in the president’s budget could eliminate this incentive—but only if the BBA’s hike in manufacturer rebates to 70 percent are undone.

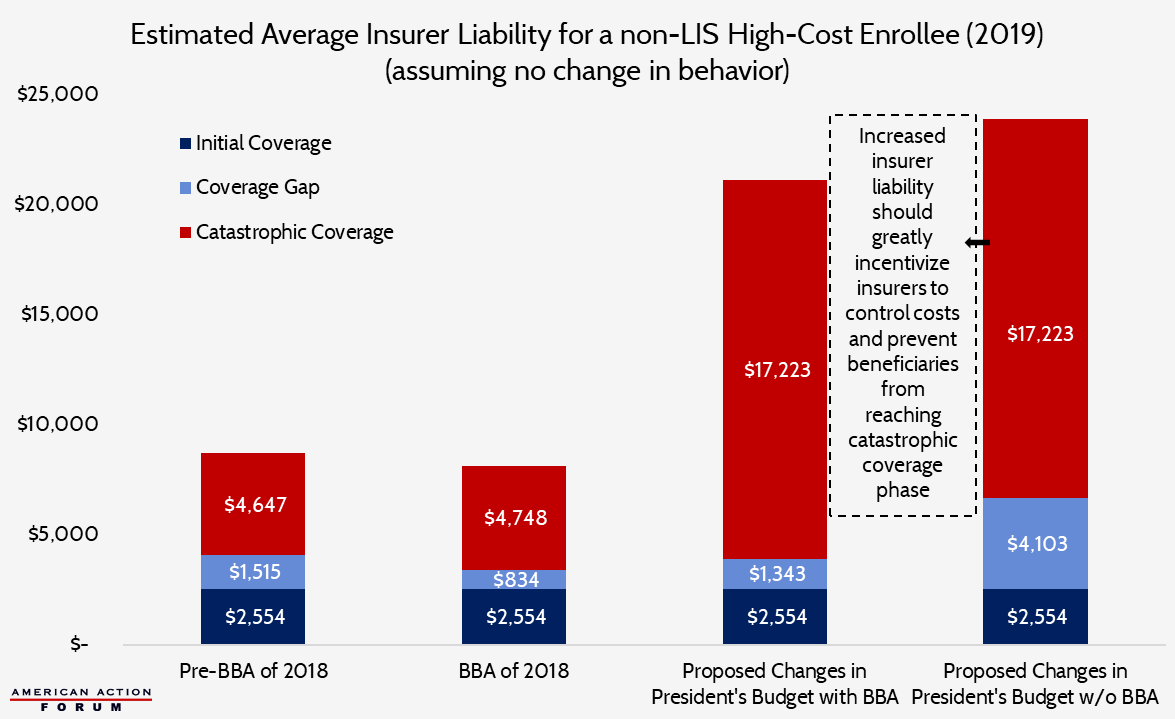

The chart below shows how the budget proposals would reshape insurer liability (assuming there is no change in expected beneficiary expenditures) if applied with and without the BBA’s changes regarding manufacturer rebates.

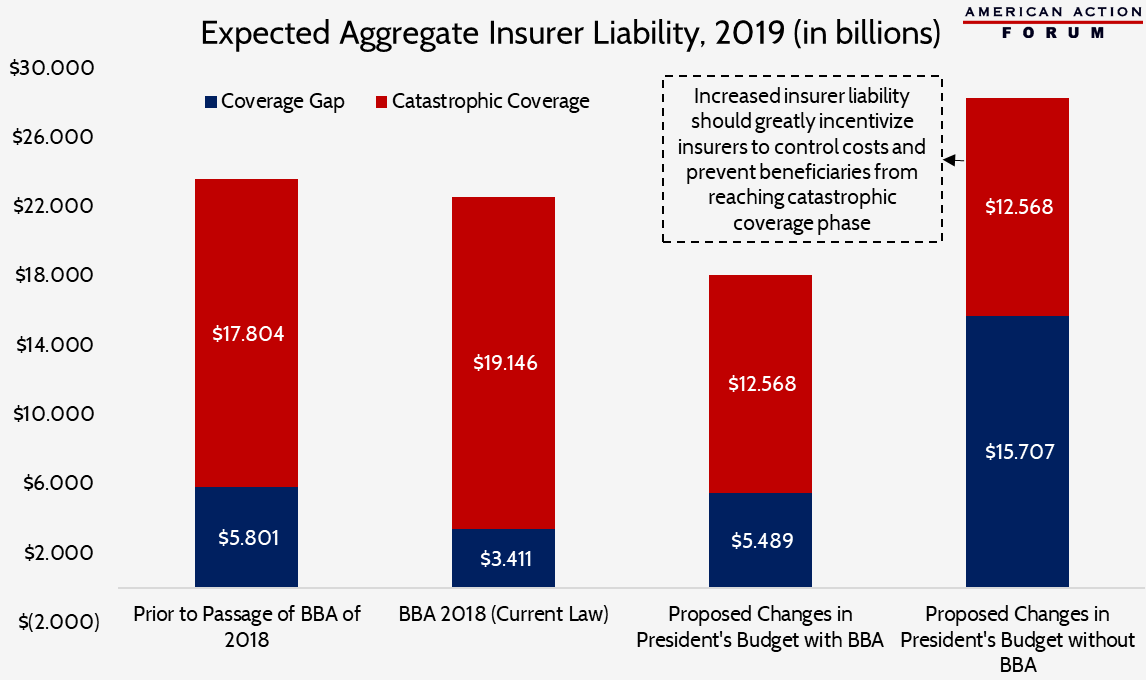

On a per beneficiary basis, there does not appear to be a dramatic difference between the two different scenarios in which the president’s proposed changes are applied. However, when insurers’ liability is considered in the aggregate, accounting for the number of beneficiaries expected to reach each coverage phase, the change in incentive becomes quite obvious.

The BBA reduced insurer liability in the coverage gap from 25 percent to 5 percent, which accounts for the substantial reduction in their coverage gap costs on a per capita basis and the bulk of their expected savings in the aggregate. Additional savings in the coverage gap would result from the reduction in overall spending that must occur before a beneficiary moves into catastrophic coverage—5 percent of a smaller number is obviously going to be less. For the same reason, insurer liability in the catastrophic phase will increase slightly on both a per person basis and in the aggregate, because of a larger share of a beneficiary’s costs being paid in the catastrophic phase and slightly more people reaching catastrophic coverage. On net, insurers are expected to save more than $1.05 billion given these changes.

Under the president’s budget, manufacturer rebates would no longer count toward a beneficiary’s OOP costs. As a result, the amount of total spending that must occur before a beneficiary moves into the catastrophic phase would more than double to $18,658, regardless of whether the BBA’s changes increasing manufacturer rebates are kept or not, which will significantly reduce the number of beneficiaries who reach the catastrophic phase. The different outcomes under the two scenarios—and the divergent insurer incentives that result—depend on who covers most of that cost: the drug manufacturer or the insurer. With both the BBA’s increased manufacturer rebates and the president’s budget proposals in effect together, net insurer liability is reduced another $4.5 billion, for a net reduction in insurer liability of $5.6 billion in 2019 relative to the pre-BBA status quo.

One interesting effect in this scenario is that insurer liability in the coverage gap nears the level it was prior to passage of the BBA, despite the percentage of the costs for which they are responsible dropping by 80 percent. This rise is due to the increased spending that will occur in the coverage gap, as explained earlier, and will also result in manufacturer rebates being nearly four times greater for each high-cost enrollee. Similarly, because far fewer patients (likely less than 2 percent based on current trends) will reach the catastrophic phase, and far fewer costs will be incurred there, insurer liability there will be reduced drastically.

If the proposals outlined in the president’s budget were implemented without the increased manufacturer rebates required by the BBA, insurer liability increases to $28 billion, a nearly $5 billion increase relative to expectations prior to passage of the BBA. This is because they would once again be responsible for 25 percent of all costs in the coverage gap, while the other effects outlined in the previous scenario that drive up insurer’s liability would still hold true. Aggregate liability in the catastrophic phase would be the same with or without the BBA, unless there are behavioral changes.

In this scenario (the president’s budget implemented without the BBA’s changes), insurers’ financial incentives would be properly aligned to encourage insurers to manage costs more effectively throughout the various stages of coverage. To help insurers in this regard, the president’s budget also proposes allowing insurers greater flexibility in developing their plan formulary as well as expanded use of utilization management tools.

Reducing Government Costs

Since the government currently pays such a large portion of the costs in the catastrophic coverage phase, the perverse incentives to use high-cost/high-rebate drugs hurt taxpayers especially. Since 2010, the number of high-cost enrollees has increased 10 times faster than in the years prior to that, and per capita expenditures for each of these high-cost enrollees grew at an average annual rate of 10.4 percent between 2010 and 2015.[16] As a result, total government expenditures in the catastrophic phase, also referred to as reinsurance, grew at an average annual rate of 26 percent from 2010-2016—more than double the rate of growth from 2007-2010—reaching $34.8 billion in 2016.[17] Over time, the government’s reinsurance subsidy has become a much greater share of the overall federal financing of the program, accounting for 56 percent of the total federal subsidy in 2017, more than double the share in 2007.[18]

An independent analysis assessing the Part D program structure came to the same conclusion as MedPAC—that the current program structure fails to incentivize plan sponsors to control costs sufficiently, and substantially increasing insurer liability in the catastrophic phase of coverage would likely provide insurers the needed incentives.[19]

The government is expected to save money, but the extent of those savings are largely dependent upon behavioral changes, making it difficult to analyze. Savings from the reinsurance phase would be offset by increases in other areas. Insurers would need to account for their increased liability, and premiums would rise as a result. However, because the government finances a fixed 74.5 percent of overall Part D program costs, the government’s direct subsidy of beneficiary premiums would also increase. This increase in government spending on the premium would largely offset the expected increased cost to the beneficiary, but it would also offset some of the savings from reduced reinsurance expenditures. Nevertheless, the government is expected to save money as insurers are expected to continue finding innovative ways to control program costs and improve patient health. Indeed, by making them more liable for patient costs in the catastrophic phase, they are encouraged to do so.

Conclusion

The Medicare Part D prescription drug program is a highly successful government entitlement program. However, one particular design feature creates a perverse incentive for plan sponsors to prefer coverage of high-cost, high-rebate drugs, at the expense of taxpayers. A change in the BBA of 2018, even though it would save patients money in the short term, threatens to exacerbate this problem and diminish the incentive for plans to control program costs, driving up costs for everybody in the long term. The president’s FY 2019 budget proposal includes additional changes to the Part D program structure which, if implemented, could restore and even increase plans’ financial incentives to control beneficiary costs throughout the various phases of coverage. However, this outcome will only be achieved if the BBA’s reduction in insurer liability in the coverage gap is reversed. These reforms are likely to change incentives enough that they have the potential to bring down overall program costs and ultimately save taxpayers money.

[1] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-16-00270.pdf

[2] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[3] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[4] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/no-limit-medicare-part-d-enrollees-exposed-to-high-out-of-pocket-drug-costs-without-a-hard-cap-on-spending/

[5] https://www.ncoa.org/wp-content/uploads/part-d-lis-eligibility-and-benefits-chart.pdf

[6] https://www.kff.org/medicare/issue-brief/no-limit-medicare-part-d-enrollees-exposed-to-high-out-of-pocket-drug-costs-without-a-hard-cap-on-spending/

[7] https://www.kff.org/report-section/no-limit-medicare-part-d-enrollees-exposed-to-high-out-of-pocket-drug-costs-without-a-hard-cap-on-spending-issue-brief/

[8] MedPAC Report to Congress, March 2018, pg 425: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf

[9] MedPAC Report to Congress, March 2018, pg 424: http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf

[10] Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, Announcements and Documents: https://www.cms.gov/Medicare/Health-Plans/MedicareAdvtgSpecRateStats/Announcements-and-Documents.html

[11] 2017 Medicare Trustees Report: https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/ReportsTrustFunds/Downloads/TR2017.pdf

[12] https://oig.hhs.gov/oei/reports/oei-02-16-00270.pdf

[13] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[14] https://q1medicare.com/PartD-The-MedicarePartDOutlookAllYears.php

[15] https://www.kff.org/report-section/no-limit-medicare-part-d-enrollees-exposed-to-high-out-of-pocket-drug-costs-without-a-hard-cap-on-spending-issue-brief/

[16]http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[17] http://www.medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar18_medpac_ch14_sec.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[18] http://medpac.gov/docs/default-source/reports/mar17_medpac_ch14.pdf?sfvrsn=0

[19] http://www.nber.org/papers/w24240?utm_campaign=ntw&utm_medium=email&utm_source=ntw